HOME INFLUENCES AND EXPERIENCES - LOVE OF MUSIC AND THE FACULTY OF MEMORIZING TUNES A SOURCE OF PERENNIAL HAPPINESS

“Music, how powerful is thy charm

That can the fiercest rage disarm,

Calm passions in the human breast,

And bring new hope to a mind distrest;

With amorous thoughts the soul inspire,

Or kindle up a warlike fire,

So great is music’s power.

Inflamed by music soldiers fight,

Inspired by music poets write;

Music can heal the lovers’ wounds,

And calm fierce rage by gentle sounds;

Philosophy attempts in vain,

What music can with ease attain,

So great is music’s power.”

COLLECTING and preserving from oblivion the cherished melodies of one’s native land must be regarded as a pleasure or pastime, and not an occupation, for none but those to whom music appeals instinctively and over whom it exercises an almost divine fascination would devote to it the time and talent which might be employed more profitably in gainful pursuits.

The music of Ireland is all that her oppressors have left her, and even that she is now losing by the indifference of her people. Our national music is a treasure, in the possession of which we should be justly proud, and as a writer in the Dublin University Magazine expressed it: there are few laborers in the service of Ireland to whom we should feel more grateful than to those who have devoted their talents and their time to its preservation. Believing as we do that the ancient melodies of a country afford us one of the most unerring criterions by which we can judge of the natural temperament and characteristic feelings of its people, we think it an object of the highest importance that as many examples of such strains as can be found in every country where they exist should be collected and be given to the public in a permanent form. Viewed in this way, the melodies of a country are of more value than they have been usually esteemed.

To posterity the zeal and self-sacrifice of the collector of Folk Music may be inestimable. For his reward, beyond the delights experienced in congenial studies, the collector must be content with the appreciation of those kindred spirits to whom music is the absorbing passion of their lives.

Impelled by a soulful desire to possess, for personal use, but more often for the purpose of preserving and disseminating the remnants which have survived of our musical heritage, a continuous chain of collectors and publishers of Irish melodies have, for nearly two hundred years, been engaged in this praiseworthy work, down to the present day, and it may be safely assumed that little of importance remains to be done in that line of effort by future enthusiasts.

Rarely, if ever, has the collection of Irish music been undertaken as a commercial enterprise, and owing to singularly unfortunate national, political and industrial conditions in Ireland, it is doubtful if any such undertaking ever justified the hopes of its promoters.

A later chapter, devoted to the enumeration and description of the many and various collections of Irish music published since early in the eighteenth century, will no doubt prove a revelation to the majority of readers; few having any conception of the extent to which that fascinating hobby has been pursued in the past.

From the accusation of having included in their lists, airs or tunes previously published, no collector is exempt. All, unless the first few, have perhaps unwittingly transgressed in this respect, and it is well that they did, for few airs obtained from different sources are identical. The influence of locality and individual preference constantly tend to vary original strains, and as musical compositions were preserved in the memory and mainly transmitted without notes from one generation to another, imperfect memorizing would account for the bewildering variety of strains traceable to a common origin.

A few generations ago, and down to the days of our grandparents, the harper, the union piper, the fiddler, and even the dancing-master, were cherished institutions. They met with cheerful welcome at the homes of the gentry and well-to-do peasantry throughout Ireland, and enjoyed the hospitality of their hosts as long as they cared to stay.

The pages of Carleton, Shelton Mackenzie, and other writers afford us many pleasant sketches of those characteristic features of Irish life in days gone by; and whatever causes may have led to the lamentable changes in rural life in Ireland in the nineteenth century, it is painful to note that little in the form of enjoyable entertainment is within the reach of the present generation.

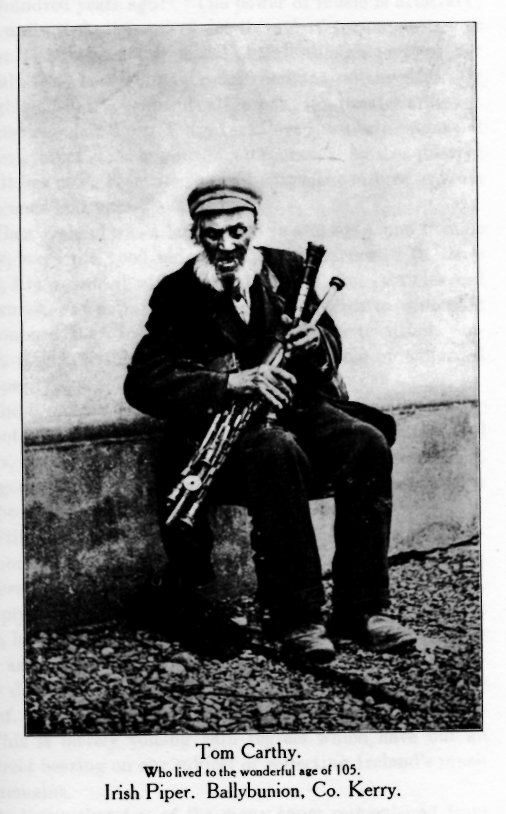

Although the renowned harpers were rapidly diminishing in number at the end of the eighteenth century, the race did not become entirely extinct until early in the nineteenth century. The pipers, more popular even than the harpers, among the peasantry continued to thrive, and kept the national music alive and in vigorous circulation until the blighting famine years decimated both them and their patrons. For centuries music was the only means of livelihood available to the blind in Ireland; consequently, the afflicted practically monopolized the profession.

How the glad tidings flew far and wide when a piper or fiddler paid one of his periodical visits to a community, and with what delight did the simple, light-hearted people, young and old, boys and girls, look forward with thrills of anticipation to the evenings when they could call at the “Big house” and listen to the grand old inspiring music which finds a home in our hearts, and refuses to leave, go where we may, until life itself departs.

How often do we hear of Erin’s exiles, whether on the sun-scorched plains of Hindustan, the snow-clad barrens of Alaska or beneath the Southern Cross, melted to tears or roused to unexampled valor, on hearing the strains of a cherished melody that recalled the sounds and scenes of their youth. Well has Hadow said: “Music, of all the arts, is the most universal in its appeal. From the heart it has come and to the heart it shall penetrate, and all true music shall take these words for its maxim.

The power of music over the soul is not to be defined: it appeals to every heart; it raises every latent feeling; so opposite are the sensations it inspires, that it will sometimes soothe the breast of misery, and sometimes plunge the arrow deeper; sometimes it draws the tears of sympathetic feeling even from the eye of happiness, or calms the rage of the unlettered savage.

To quote the words of an anonymous Irish writer of one hundred years ago: “The power of music is arbitrary; it is unlimited; it requires not the aid of reason, justice or honor to protect it; it is delightful, though perhaps not useful; it is bewitching, though perhaps not needful. It delights all hearts; expands all minds; it animates all souls. It inspires devotion; it awakens love; it exalts valor; it rouses sympathy; it augments happiness; it soothes misery; and it has often been used as an instrument to lure us from innocence and peace.”

When Ireland was a land of music and song, and fireside story, were the good old times in real earnest. In those days, life, seasoned with national and rational pastimes and pleasures, was more enjoyable and conducive to contented nationhood than in the first decade of the twentieth century, although the savings banks tell a tale of enhanced prosperity.

The Sunday afternoon “Patrons,” which terminated the monotony of a weary week, and the flax “Mehil” dances and plays, which relieved the dreariness of the winter season, are gone and now but a memory to the aged and a tradition to the young.

With the discontinuance of those simple yet ancient diversions which the peasantry of every country but Ireland is permitted to enjoy, according to their taste and custom, the piper, the ballad-singer, and the fiddler also, it may be said, have followed the harper into extinction, so that virile and ambitious youth, unable longer to endure the intolerable dullness at home, is fleeing to the emigrant ship for relief.

This is merely voicing vain regrets which have but an indirect bearing on our subject of collecting Ireland’s musical remains.

Realizing that few of the many tunes remembered from boyhood days, and others acquired in later years, were known to the galaxy of Irish musicians domciled in Chicago, the writer decided to have them preserved in musical notation. This was the initial step in a congenial work which has filled in the interludes of a busy and eventful life.

Heedful of the dictum of the sociologist who proclaimed that the proper way to train a boy is to commence with his grandmother, the author of those sketches has deemed it advisable to begin with his grandfather.

O’Mahony Mor, or as he was generally called, “The Cianach Mor” - his clan title - kept open house in the old days in the glens of West Cork, not far from Castle Donovan, for the wandering minstrels of his time, who came that way, and it is owing to that characteristically Irish spirit of hospitality that the writer, his grandson, is now telling the story. Born and brought up in such a home, amid an environment of traditional music and song, it was to be expected that my mother - God rest her soul - would memorize much of the Folk Music of Munster and naturally transmit it orally by her lilting and singing to her children, inheriting a keen ear, a retentive memory, and an intense love of the haunting melodies of their race. Similarly gifted was our father, who, full of peace, and content, and occupying his accustomed chair beside the spacious fireplace, sung the old songs in English or Irish for his own pleasure, or the entertainment of those who cared to listen, of whom there were many not included in the family. Like the glens among the Ballyhoura Mountains, where Dr. P. W. Joyce imbibed and accumulated the hundreds of tunes which he has published, the glens and valleys in Southwest Cork were also storehouses of musical treasures unexplored by the great collectors of Irish melodies, Bunting and Petrie, whose work has won them undying fame.

Pipers, fluters and fiddlers were far from scarce in the early part of the nineteenth century, and between “Patrons” at the crossroads in summer and flax “Mehils” at the farmhouses in the winter, the tunes and songs were kept alive and in circulation, thereby adding zest and variety to an otherwise monotonous country life.

There were two pipers in our parish - Peter Hagerty, locally known as the “Piobaire Ban,” on account of his fair hair, and Charley Murphy, nicknamed “Cormac na Paidireaha.” Murphy was a respectable farmer’s son, who got a “blast from the fairies” one dark night, while engaged in ‘ catching blackbirds and thrushes among the furze hedges with the aid of straw torches. Becoming very lame as a result of the fairies’ displeasure, he took to playing the pipes and soon acquired creditable proficiency, based on his previous skill as a flute player.

In those days succeeding the famine years, Irish was much spoken, and such children as did not get an education in English were obliged to learn their prayers and catechism from oral instruction in the Irish language. Our piper, being fluent in both languages and experienced in “Answering Mass,” was chosen as instructor, and between his income from those sources and a prosperous “Patron” which he established at Tralibane Bridge, and playing at an occasional farmhouse dance, he managed to make a fair living.

With what wonder and curiosity we youngsters gazed on this musical wizard, as he disjointed his drones and regulators and tested the reeds and guills with his lips, over and over again, with exasperating deliberation. The impatience of the dancers never disconcerted him, for I really believe his actions were prompted by a desire to impress them by his seeming technical knowledge of his complicated instrument. One part of the tune was generally well rendered, but when he came to “turn it” or play the high strain his performance too frequently left much to be desired.

Peter “Bawn” or Hagerty, a tall dignified man, blind through smallpox since childhood, was an excellent piper, the best in West Cork. He had a “Patron” at Colomane Cross, was married, and maintained himself and wife in comparative comfort, until a new parish priest, unlike his predecessor, having no ear for music or appreciation of peasant pastimes, forbade “Patrons” and dances of all kinds in the parish.

The poor afflicted piper, thus deprived of his only means of making a livelihood, finally took refuge in the poorhouse - that last resource of helpless poverty and misfortune - and died there. To this day I remember a few of his tunes, picked up in early youth, but forgotten, it seems, by every one else in that part of the country.

On one occasion Peter “Bawn” was playing at a dance in a farmhouse separated only by a stone wall from my sister’s dwelling. Being young and insignificant I was put to bed, out of the way, while the others went to enjoy the dance next door. It just chanced that the piper was seated close to the partition wall mentioned. Half asleep and awake the music hummed in my ears for hours, and the memory of the tunes is still vivid after the lapse of fifty years.

Many fine tunes were peculiar to certain

localities in remote and isolated valleys in Ireland.

Jerry Daly,

a noted dancer now nearly ninety years of age, and living in Chicago,

has no regard for musicians who can’t play the tunes he knew when

he gave exhibitions of his skill “dancing on the table” to Peter

“Bawn’s” music. Small blame to the musicians, for those tunes

were unknown beyond a very limited circuit even then, and are

entirely forgotten there now.

At another time, when a dance was given in my father’s house, I was sent upstairs to be out of the way. The fascination of the music kept me awake, and young as I was, two of the tunes heard on that night still haunt my memory. John O’Nei1l, my father’s namesake but no relative, played the German flute in grand style. He always carried with him, on such occasions, a light pair of dancing shoes, in which to display his Terpsichorean ability. He never married, and when he had grown too old to Work, the sordid “strong farmer” in whose service he had spent his life, ungenerously carted him off to the poorhouse, where old age, reinforced by humiliation and grief, soon swept him into eternity “unwept, unhonored and unsung” - sad ending for a man who through life contributed so much to the happiness of others.

The rudiments of music on the flute were kindly taught me by Mr. Timothy Downing, a gentleman farmer in Tralibane, our townland. He was an accomplished performer on several instruments, but the violin was his favorite. He never played outside his own residence, and there only for a favored few. Humming a tune as he played it, was one of his peculiarities. How often since leaving home, at the age of sixteen, have I longed to get a glimpse of the chest full of music manuscript which he possessed, and from which he selected the tunes for my lessons. My wish has since been gratified, unexpectedly, for on a recent visit to Ireland I found some of it treasured by his daughter, Miss Jane, at the old homestead, and the rest of it in the possession of his son, T. A. Downing, at Bangor Wales. In addition to the tunes memorized from his playing in my boyhood there were found among his manuscripts several unpublished melodies - such as, “Open the Door for Three,” “Three Halfpence a Day,” and a rare setting of the hop jig, named “I have a Wife of My Own.” Except two tunes - “Far From Home,” a reel, and “Off to California,” a hornpipe, picked up in the San Joaquin Valley, California, in my nineteenth year, no Irish music was added to my repertory until I became a school teacher at Edina, Knox County, Missouri, where I attained my majority.

Music has had, at all stages of life, a strange influence on my destiny, not the least of which was the following instance.

The full-rigged ship Minnehaha, of Boston, on which I served “before the mast,” was wrecked on Baker’s Island, in the mid-Pacific. Our crew, numbering 28, were taken off this coral islet after eleven days of Robinson Crusoe experiences by the brig Zoe, manned by a white captain and a Kanaka crew. Rations were necessarily limited almost to starvation. One of the Kanakas had a fine flute, on which he played a simple one strain hymn with conscious pride almost every evening. Of course, this chance to show what could be done on the instrument was not to be overlooked. The result was most gratifying. As in the case of the Arkansas traveler, there was nothing too good for me.

My dusky brother musician cheerfully shared his “poi” and canned salmon with me thereafter. When we arrived at Honolulu, the capital of the Hawaiian Islands, after a voyage of thirty-four days, all but three of the castaways were sent to the Marine Hospital. I was one of the three robust ones, thanks to my musical friend, and was therefore sent straight on to San Francisco. What became of my wrecked companions was never learned; but it can be seen how the trivial circumstance of a little musical skill exercised such an important influence on my future career.

Mr. Broderick, the school director with whom I boarded at Edina, was a native of Galway and a fine performer on the flute. Not a week passed during the winter months without a dance or two being held among the farmers. Such a motley crowd - fiddlers galore, and each with his instrument. Irish, Germans, French - types of their respective races-and the gigantic Kentuckians, whose heads were endangered by the low ceilings, crowded in, and never a misunderstanding or display of ill-nature marred those gatherings. Seated behind the fiddler, intent on picking up the tunes, was my accustomed post, but how much was memorized on those occasions cannot now be definitely stated. Three tunes, however, distinctly obtrude on my memory, viz.: A reel played by Ike Forrester, the “village blacksmith,” which was named after him; “My Love is Fair and Handsome,” Mr. Broderick’s favorite reel; and a quickstep, which I named “Nolan, the Soldier.” Nolan had been a fifer in the Confederate army during the Civil War. His son was an excellent drummer, and both gave free exhibitions of their skill on the public square at Edina to enliven the evenings while the weather was fine.

Residence in a large cosmopolitan city like Chicago affords opportunities in various lines of investigation and study not possible in other localities. Within the city limits, a territory comprising about two hundred square miles, exiles from all of Ireland’ s thirty-two counties can be found. Students in pursuit of any special line of inquiry will find but little difficulty in locating people whose friendship and acquaintance they may desire to cultivate.

Among Irish and Scotch music lovers, every new arrival having musical taste or talent is welcomed and introduced to the “Craft,” to the mutual advantage of all concerned, and there is as much rejoicing on the discovery of a new expert as there is among astronomers on the announcement of a new asteroid or comet.

During the winter of 1875, James Moore, a young Limerick man, was in the habit of spending his evenings at my home on Poplar Avenue. His boarding-house across the street, although plastered, was yet without doors and far from comfortable, compared to a cosy seat on the woodbox back of our kitchen stove. Not having a flute of his own, he enjoyed playing on mine, and, being an expert on the instrument, it can well be imagined how welcome he was. While he had a wonderful assortment of good tunes, he seemed to regard names for them as of little consequence - a very common failing. Of the reels memorized from his playing, the “Flower of the Flock,” “Jim Moore’s Fancy,” and the “New Policeman” were unpublished and unknown to our people except Mr. Cronin, who had variants of the two last named. The “Greencastle Hornpipe,” one of the best traditional tunes in our collections, also came from Moore, as well as many others too numerous to mention. He went to New York in the spring and was never heard from after in Chicago.

Membership in the Metropolitan police force, which was joined in 1873, broadened the field of opportunity for indulging in the fascinating hobby of which I am still a willing victim. Transfer from the business district to the Deering Street station, was particularly fortunate. It was largely an Irish community, and of course traditional musicians and singers were delightfully numerous.

A magnificent specimen of Irish manhood and a charming fluter was Patrolman Patrick O’Mahony, commonly known as “Big Pat.” His physique would almost justify Kitty Doherty’s description of her lamented father, in her testimony before a Toronto magistrate: “He was the largest and finest looking man in the parish, and his shouldhers were so broad that Murty Delaney, the lame tailor, and Poll Kelly, could dance a Moneen jig on them, and lave room for the fiddler.”

Born in West Clare, his repertory of rare tunes was astonishing, the “swing” of his execution was perfect, but instead of “beating time” with his foot on the floor like most musicians he was never so much at ease as when seated in a chair tilted back against a wall, while both feet swung rhythmically like a double pendulum. Unlike many performers on the flute, whose “puffing” was so distressing and unpleasant, “Big Pat’s” tones were clear and full, for his wind was inexhaustible.

From his playing I memorized the double jigs “Out on the Ocean,” the “Fisherman’s Widow,” the “Cliffs of Moher,” and several others. Among the reels learned from him were: “Big Pat’s Reel,” “Happy Days of Youth,” “Miss Wallace,” “Little Katie Kearney” and “Lady Mary Ramsey,” or “The Queen’s Shilling”; also “The Thunder Hornpipe” and “Bantry Bay,” one of the most delightful traditional hornpipes in existence.

Many an impromptu concert in which the writer took part enlivened the old Deering Street Police Station about this time. An unique substitute for a drum was operated by Patrolman Michael Keating, who, forcing a broomhandle held rigidly against the maple floor at a certain angle, gave a passable imitation of a kettle drum. His ingenuity and execution never failed to evoke liberal applause.

It was soon learned that a local celebrity, John Conners, famed as a piper, lived in the district. When found, he proved to be an affable, accommodating business man whose musical talent was not in great demand at home. He was willing to play for me anywhere but in his own house when he had his instrument in order after long disuse. Being then unacquainted with the famous pipers residing in other parts of the city, I envied Mr. Conners his skill on a set of pipes which were neither Irish nor Scotch, but a combination of both. He kindly left them in my custody for months, so that by assiduous practice my former envy was transferred to him. Mr. Conners was a native of Dublin, and one of his juvenile pranks which he mentioned with pride was the capture and larceny of a patriarchal goat, whose hide was urgently needed to make a new bag and bellows for a set of Union pipes.

Before the Civil War he played on the Mississippi steamboats plying out of Memphis, Tennessee. While he prided himself on his fancied superiority in playing Irish airs, his memory will remain fresh and green longer on account of one particular jig, called “The Gudgeon of Maurice’s Car,” which he alone knew. The weird tale in connection with this now famous tune will be told in another chapter, so we will return for the present to the Deering Street Police District.

Within a few squares of the police station lived the Maloneys, a noted family of musicians - Denis, Dan, Tom and Mary - all good performers on the German flute. I believe all have passed away, except the first named, who resides in South Chicago, a hale, hearty old man and capable of holding his own yet with the best of them. He played with Delaney and Murnihan, piper and fiddler respectively, at the Gaelic Society entertainments and other occasions in recent years. Their father, a rather lively old man, was an agile dancer, but the rheumatism in one of his legs seriously handicapped him when dancing to the music of Jimmy O’Brien, a Mayo piper who spent a few months among us in the early seventies. While attempting to dance a certain jig, then to me unknown, he appealed to the piper, in strident tones, “Single it, single it; I can’t double with the other foot.” This concession granted, he continued for a time, amidst great applause. The jig alluded to I memorized, and, being without a name, it was christened “The Jolly Old Man,” in honor of Mr. Maloney. In later years a version of it, found in an old volume, was entitled “The Brisk Young Lad.” It is also called “The Brisk Irish Lad.” In a set of country dances, printed in London for the year 1798, and in Volume 1 of Aird’s “Selection of Scotch, English, Irish, and Foreign Airs,” published in Glasgow in 1782, a version of it is called “Bung Your Eye.”

O’Brien was a neat, tasty Irish piper of the Connacht school of close players, and though his Union pipes were small, they were sweet and musical. To what extent I was indebted to him for tunes is a question not now easily determined, but there is no doubt that from his playing I picked up “Jimmy O’Brien’s Jig” and the reels “Mary Grace,” “The Woman of the House,” “Jenny Picking Cockles” and “The Star of Munster,” and several others. The first named reel was entirely unknown even to musicians from O’Brien’s native county. In later years we found a fair version of it, as “Copey’s Jigg,” in an extremely rare volume of Irish music, called “The Bee,” but undated. Under the same name it was also printed in Clinton’s “Gems of Ireland,” published in London in 1841. O’Briens style of it is much to be preferred. One of his peculiarities - and an unpleasant one, occasionally - was a habit of stopping the music in order to indulge in conversation. He could not be induced to play a tune in full, when under the influence of stimulants, as his loquacity was uncontrollable, and he never hesitated under such conditions to express a passing sentiment.

Amiable and harmless at all times, he died at a comparatively early age in Chicago, a victim to conviviality, his only weakness.

A musical star of great magnitude appeared in Chicago from the eastern cities in 1880. John Hicks, celebrated from Washington to Boston as a great Irish piper, accompanied by the no less renowned Irish dancer, Neill Conway, came to fill a theatrical engagement. They won immediate popularity, but, unfortunately, Conway had brought his eastern failings with him, and before Hicks knew it, his light-footed partner had squandered their joint salaries. As he had defrayed all traveling expenses from New York even to the extent of paying for Conway’s dancing shoes, Hicks found himself short of funds. This led to his playing in Conley’s saloon, in Des Plaines Street, where he attracted a large and cosmopolitan audience. Differing from most pipers in many respects, he played modern airs, schottisches, waltzes, and polkas, to suit the most fastidious company. In short, he was a thorough musician, could read music on sight and transpose the key of any tune at pleasure, having been a protege of the “Sporting” Captain Kelly of the Curragh of Kildare.

On one occasion he was encountered on State Street whistling from the sheet music displayed in the window of a music store. He inquired if I knew of any place where he could earn some money. Remembering James Rowan, a well-to-do property owner near the Bridgeport rolling mills, whom I had often heard remark that he would gladly give five dollars any time to hear a good reel on the Irish pipes, this appeared to be a fortunate opportunity to favor two interests at one time. So, together, we called on the liberal patron of pipe music without delay. We found this large-hearted man Rowan contentedly gossiping in O’Flaherty’s tailor shop, and were received with every outward appearance of pleasure. Piper Hicks rolled out reel after reel in his best style for an hour or so, evoking only responsive grunts of approval from Rowan. Doubtless he remembered his boasts and my knowledge of them; hence the unsympathetic chill in his demeanor which betrayed his membership in the “Tightwad Club.”

We withdrew with the best grace posible, but my humiliation was such that I borrowed five dollars from a friend and forced Hicks to take it, thus becoming eligible myself to full membership in the “Idiotic Order of E. Z. Marks.”

An engagement of three weeks at St. Bridget’s church fair was in striking contrast to our late disappointment. Such was the popularity and fame of Hicks’ playing that a detail of police had no easy time in regulating the crowds which came from far and near to hear him and dance to his music. Whenever possible, the writer was on hand, charmed beyond expression by the precision, rhythm and melody of his execution. Of the many tunes picked up from his playing, one at least, is the double jig “Paddy in London,” and another is “Hicks’ Hornpipe,” named for him, but never heard or found elsewhere. A delightful hornpipe of five strains, named “The Groves,” was beyond my powers of memorizing completely in the limited opportunities presented, and its loss, with slight prospects of recovery, was much regretted.

Through Patrick Touhey, an even greater performer on the Union pipes in a younger generation, we obtained an excellent setting of this fine traditional tune, and it has since been printed in O’Neill’s Music of Ireland. A good version of it was later published in Petrie’s Complete Collection of Irish Music.

Hicks’ wonderful music was the talk of the town. Old Mike Finucane, an ex-alderman and still a very important personage in the ward, was very anxious to hear him, but on account of his rheumatism was unable to attend the fair. The piper, always gracious, obligingly visited the great man at his residence, and entertained him for half an hour. Hicks was giving some extra flourishes to “Garryowen,” by way of variations, when, relaxing his dignity, Mr. Finucane waved his hands in glee and shouted, approvingly, “That’s all of it now - that’s the whole of it - and it can’t be bate; I often heard `St. Patrick’s Day’ played before, but this is the first time I ever heard anyone play the whole of it.” With sincere approval of his abilities from such a distinguished authority, the piper’s smiles, on leaving, could not well be misunderstood.

I came near forgetting to mention that “Blind Murphy,” whose eccentricities will be dealt with in a chapter on “Amusing Incidents,” called on Mr. Hicks one morning to have his pipes put in order. “Put them on yourself, Mr. Murphy, as then I can tell best what is necessary,” said Hicks, on learning Murphy’s mission. The latter willingly complied, and wheezed out a few of his favorite tunes. “Play something,” suggested Hicks, who evidently failed to realize that his visitor had already done his level best. This was too much for Murphy, who imagined he was doing wonders. In fact, his pride had been wounded and, unbuckling his instrument, he promptly departed, in no pleasant frame of mind.

This calls to mind another Murphy, a. New York piper, who abandoned his occupation as coachman and came to Chicago to engage in business. He was a great romancer and professed his ability to play on all kinds of bagpipes equally well. His pretensions aroused some suspicion, so arrangements were made to put him to the test. Unexpectedly, and to his great confusion, after declaring his ability to finger the Scotch chanter like a Highlander, a nice set of Scotch pipes with drones arranged in a stock and blown with a bellows like the Irish or Union pipes, was handed to him. He endeavored to excuse himself on the plea of not feeling so well that evening, but he couldn’t get out of it. He was fairly caught, and this fiasco punctured his pretensions.

The strains of a slashing but unfamiliar reel floating out on the night air from the lowered windows of Finucane’s Hall caught my eager ear one Saturday night, when Tommy Owens was playing for a party. Being on duty as Desk Sergeant at the time, and as the police station was just across the street, I had little difficulty in memorizing the tune. Although it had never been printed it soon gained wide circulation among experts, and it had become such a favorite with Inspector John D. Shea, that it has since been identified with his name. It is printed in O’Neill’s Music of Ireland, under its original title, “The Ladies’ Pantalettes.”

While yet attached to the Deering Street Station as desk sergeant, I heard of John K. Beatty, a native of County Meath, who had quite a reputation as an Irish piper. He lived in an unfinished house into which altered fortunes obliged him to move from a pretentious mansion in Hyde Park, but his good humor and blinding egotism evidently had not suffered by the change. Nothing pleased him better than an audience, only they must be demonstrative in their appreciation in order to obtain the best results. This saved time, for if they relaxed at all in catering to his vanity he suspended the performance to tell how much superior he was to all other pipers. Yet withal he was the soul of geniality, and did not intend to reflect on anybody. It was not that they were poor or indifferent players, but that his superlative excellence put him in a class all by himself. Execution - too much of it - he had, but neither time nor rhythm. He was truly the dancer’s despair, although an excellent dancer himself. In humming or lilting he was incomparable, but he couldn’t for the life of him bring it that way out of the chanter. One call satisfied my curiosity, and besides, I felt unequal to the task of applauding a performance more amusing than edifying. Our friendship and mutual respect, however, remain unshaken to this day.

An American lady, of wealth and social distinction, proud of her Irish ancestry, once appealed to us for aid in getting out a suitable programme. The best Irish talent obtainable was engaged. But how about Mr. Beatty? It was contended that he could play “The Banks of Claudy” with trills and variations in an acceptable style, yet no one could guarantee that he would confine himself within limits. In any event he was the typical bard in appearance. His confident air and florid face, adorned with a heavy white mustache, and a head crowned with an abundance of long white hair, would naturally appeal to an Irish audience, so his name was placed on the programme, well towards the end, to minimize the effect of his possible disregard of instructions.

When his time came to execute “The Banks of Claudy,” he met all expectations - and much more. Intoxicated by the applause, all was forgotten but the mad desire to get more of it, so he broke loose with rhapsodical jigs and reels, his head on high, nostrils distended like a race-horse on the home stretch, while both feet pounded the platform in unison. He evidently “had it in,’ for the regulators, for he clouted the keys unmercifully, regardless of concord or effect, and when he quit, from sheer exhaustion, it is safe to say that no such deafening laughter and handclapping ever greeted an Irish piper before or since.

He was sent home in a carriage, a circumstance which he proudly attributed to his personal distinction, but, strange to say, that was his last appearance on a public platform. “When I’m dead the last of the pipers are gone,” he confided to me sadly one day. “There’s none of ‘em at all, not even Billy Taylor, of Philadelphia, could play the tunes the way I do.”

In this I agreed with him, for none of them could - or would.

“Hail, music! Sweet enchantment hail!

Like potent spells thy powers prevail;

On wings of rapture borne away,

All nature owns thy universal sway.

For what is beauty, what is grace,

But harmony of form and face;

What are the beauties of the mind,

Heav’n’s rarest gifts, by harmony combined.”