ACQUAINTANCE WITH MUSICAL IRISHMEN AND SCOTCHMEN IN CHICAGO - ENLARGED OPPORTUNITIES FOR ACQUIRING IRISH FOLK MELODIES - REDUCING THEM TO MUSICAL NOTATION COMMENCED

“Of all the arts beneath the heaven,

That man has found or God has given,

None draws the soul so sweet away,

As Music’s melting, mystic lay;

Slight emblem of the bliss above

It soothes the spirit all to love.”

FOR several years subsequent to making the acquaintance of Mr. Conners, I circulated among the Highland pipers, such as William McLean, Joseph Cant, John Monroe, Neil McPhail, John Shearer and the Swanson brothers - all Highlanders. Patrick Noonan, Tom Bowlan, and the two Sullivans, were Irishmen. Only from the two first named did I derive any addition to my stock of tunes. McLean, who was an old man, claimed to have had no rival in Scotland in his early manhood, and I can well believe it. His style and execution were admirable, and he took great pleasure in playing such Irish tunes as were possible on the limited compass of a Highland chanter, while the majority of Scotch players confined themselves to the study of such tunes as were printed in books of pipe music.

Noonan was a character, suave and persuasive as a Donegal peddler in his commercial transactions. He was a fine performer on the Highland pipes, but his ruling passion was the acquisition of bagpipes of any kind and their equipments and disposing of them to amateurs at a profit. In effecting a trade, I am afraid he not infrequently disregarded a few obligations imposed by the Ten Commandments, but the sale once made, true to the traditional hospitality of his people, he would cheerfully spend the profits with the purchaser. Naturally enough, he died early and poor.

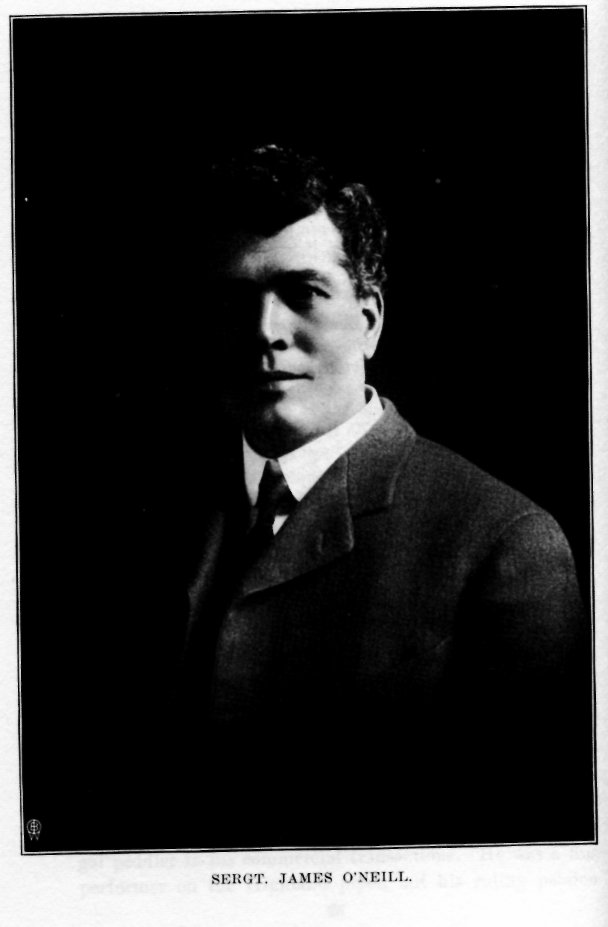

Joseph Cant, a Perthshire man, was a genial fellow who had the rare faculty of appreciating merit and good qualities in others. He wore a first prize medal won at an annual competition held at Buffalo, New York, between American and Canadian Highland pipers. It was through Mr. Cant that James O’Neill, who has been for years so intimately associated with me in collecting and popularizing the Folk Music of our race, was discovered.

A native of County Down, but long a resident of Belfast, James O’Neill was as familiar with Soottish music as Joe Cant himself, whose admiration he won by his airy style of playing flings and strathspeys on the violin. Quiet and unassuming in manner, his fine musical talent was unsuspected by his neighbors, and it was only by diligent inquiry that his address was learned. When found, he was all that our mutual friend Cant represented him to be, and much more, for his versatility in reducing to musical notation the playing, whistling, singing and humming of others, was truly phenomenal. None from the North Country possessed such a store of Ulster melodies as he, and it was chiefly because of his skill and unselfishness that the initial step in our joint work was undertaken.

Shortly after our acquaintance began, my transfer to Police Headquarters (an assignment which continued for nine years) was not conducive to successful co-operation. The acquisition of new tunes, however, suffered no abatement. According to the historian, Hume: “Almost every one has a predominant inclination, to which his other desires and affections submit, and which governs him, though perhaps with some intervals, through the whole course of his life.” Irresistibly attracted by music, and particularly Irish Folk Music, no opportunity was overlooked to gratify this inborn desire; and while at this date it cannot be estimated how many fugitive melodies were thus promiscuously acquired, it is evident the influence of this persistent pursuit on final results cannot but be considerable.

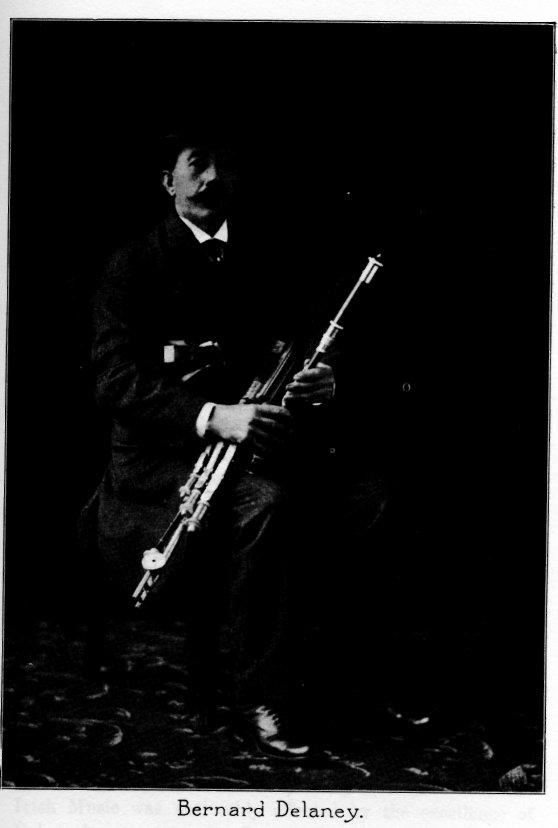

One afternoon Sergeant James Cahill happened into the General Superintendent’s office, and, knowing my interest in such matters, told me about a good Irish piper just arrived in town, who was playing in a saloon on Van Buren Street. Having been frequently disappointed in finding persons of that class not equal to their reputations, I was not prepared for the surprise in store. On reaching the building, and before entering, I knew at once that this was an exceptional instance where the musician’s abilities were underestimated. Within we found Bernard Delaney, a comparatively young man, rolling out the grandest jigs, reels and hornpipes I ever heard, and in a style unequaled by any piper we previously had met, not excepting our accomplished friend, John Hicks. His instrument was not large, but, oh, my, what a torrent of melody it poured forth! What the Rev. Dr. Henebry in later years endeavored to describe with his comprehensive vocabulary, the writer will not attempt.

Here, indeed, was a prize - and what a repertory of unfamiliar tunes he had from Tullamore, King’s County, his native place!

Without delay, Alderman Michael McNurney and Sergeant James Early, both good pipers, and a host of others of similar taste in music, came to see and hear this star of the first magnitude. Before long Delaney’s fame spread far and wide, and, being modest and unspoilt by flattery, he gained enduring friendship and prosperity. It is not to our purpose to enter into the details of what transpired about this time, except to mention that he soon had a pleasant engagement, and was accessible to all who desired to enjoy his music and learn his tunes. In the latter role the writer was by no means the least successful.

A few months had passed pleasantly for all concerned, when there came to Chicago, Power’s delightful Irish play, The Ivy Leaf. Their piper, Eddie Joyce, a brilliant young musician, took sick and was sent to a hospital. Great failings are not infrequently the concomitants of great talents, and so this precocious genius, whose fame was nation-wide, passed away in his teens, sincerely mourned by a large circle of admirers. To take his place temporarily, Delaney reluctantly consented; but such were his success and popularity, that Powers insisted on keeping him permanently on an increased salary. While we could not help congratulating Delaney, we were by no means reconciled to our loss. Nothing but a more desirable position in Chicago could be expected to allure him to return. When that had been arranged for, the writer intercepted The Ivy Leaf company in New York city and returned to the western metropolis, accompanied by our piper, where he became and still is a member of the Chicago police force. The interest in the study and practice of traditional Irish Music was noticeably affected by the excellence of Delaney’s execution, for he was in great demand as an attraction on festive and various public occasions.

Delaney, who had been traveling post for some in the Rolling Mill district, occasionally stepped into a saloon on Ashland Avenue, where a near-blind piper named Kelly nightly entertained an appreciative audience. Kelly being but recently from the East, had no suspicion of Delaney’s identity, and the latter, uncommonly mild and unassuming, gave no intimation that he knew anything about music. Of course, murder will out - Delaney was recognized, and, regardless of his remonstrance, he was carried bodily into the dining room, stripped of his uniform coat, and compelled to put on the astonished Kelly’s pipes. What followed can be better imagined than described.

Two or three years later there came to my office at Police Headquarters a modest young man who introduced himself as Patrick Touhey and said he had been advised by the great piper, “Billy” Taylor, of Philadelphia, to call on me with a view of meeting Bernard Delaney. On our way to the latter’s home I learned that Touhey had been playing for a troupe that got stranded down the state somewhere, on account of the country roads being impassable at that time of the year.

Playing together, Delaney and Touhey were a picturesque team, the former being right-handed and the latter left- handed. ‘Twas a most enjoyable evening for those who were fortunate enough to be present. Touhey proved to be another surprise, who has since developed into a wonder. In the opinion of his admirers, he has no equal. As he has adopted the stage as his profession, the public has the opportunity to hear him; and if his qualities as an Irish piper fail to meet their expectations, I’m inclined to think they will be subject to disappointment to the end of their lives.

After many years of intercourse with all manner of Irish musicians, native and foreign born, who were addicted to playing popular Irish music with any degree of passable proficiency, I began to realize that there was yet much work left for the collectors of Irish Folk Music. Many, very many, of the airs, as well as the lilting jigs, reels and hornpipes which I had heard in West Cork in my youth, were new and unknown to the musicians of my acquaintance in cosmopolitan Chicago. Neither were those tunes to be found in any of the printed collections accessible.

The desire to preserve specially this precious heritage from both father and mother, for the benefit of their descendants at least, directed my footsteps to Brighton Park, where James O’Neil1, the versatile northern representative of the great Irish clan, committed to paper all that I could remember from day to day and from month to month, as memory yielded up its stores. Many trips involving more than twenty miles travel were made at opportune times, and I remember an occasion when twelve tunes were dictated at one sitting.

Originally there was no intention of compiling more than a private manuscript collection of those rare tunes remembered from boyhood days, to which may be added some choice specimens picked up in later years, equally worthy of preservation. Drawing the line anywhere was found to be utterly impracticable, so we never knew when or where to stop.

Some difficulties were at first encountered in acquiring any tunes from some of our best traditional musicians, but curiosity in time awakened an interest in our work, and, as in the old story, those who came to scoff remained to pray, or rather play, and it was not long before the most selfish and secretive displayed a spirit of liberality and helpfulness truly commendable. Mutual exchange of tunes proved pleasant and profitable. Narrow, despicable meanness, the characteristic of the miser, whether in money or music, asserted itself in one case, however, where it was least expected or deserved, so that nothing was derived from that source except what had been already memorized from his playing.

At a Wedding in the stock yards district in the winter of 1906 I formed the acquaintance of James Kennedy, a fiddler of uncommon merit. He was the smoothest jig and reel player encountered in Chicago so far. His tones were remarkably even and full, and his selection of tunes were all gems; in fact, he had none other. It is needless to say our chance acquaintance ripened into friendship. An exception in his class, he was modest, accommodating and, rarer still, entirely free from professional jealousy. His admiration for John McFadden, whom I had not yet met, was outspoken and sincere.

From another source we learned that Kennedy’s father was a violinist of celebrity; in fact, “the daddy of them all” around Ballinamore, in the County of Leitrim. To him we are indebted for many fine unpublished tunes, such as the “Tenpenny Bit” and “My Brother Tom,” double jigs; “Top the Candle,” hop jig; and the reels “Silver Tip,” the “New Demesne,” the “Chorus Reel,” the “Ewe Reel,” the “Mountain Lark,” “Colonel Rodney,” the “Drogheda Lasses,” the “Cashmere Shawl,” “Green Garters,” the “Cup of Tea,” “Kiss the Maid behind the Barrel,” and the “Reel of Mullinavat.” The latter tune I am inclined to believe Kennedy picked up from Adam Tobin, for Mullinavat is in Kilkenny, Tobin’s native county. Inferior settings of two others have appeared in different collections.

Notwithstanding Kennedy’s opportunities. He did not play all of his father’s tunes, it seems, for it turned out that his sister Nellie, over whom he had little advantage as a violinist, played three excellent tunes learned at home, which he did not know, namely, the jig called the “Ladies of Carrick,” and the reels “Touch me if you dare” and “Peter Kennedy’s Fancy.”

Noting down tunes from dictation at his own home, or visiting those who could not conveniently call on him, kept my versatile collaborator, James O’Neill, decidedly busy. Nor was he at all slow in making discoveries by his own efforts. John Carey, one of them, was a veritable treasure. Born and grown to manhood in County Limerick and brought up in the midst of a community where old ideas and customs prevailed, his memory was stored with traditional music. He numbered among his relatives many pipers and fiddlers, and being quite an expert on the violin himself in his younger days before that archenemy of musicians –rheumatism - stiffened his fingers, his settings were ideal. Gradually, from week to week, and extending into years, his slumbering memory surrendered gems of melody unknown to this generation, and not until within a few months of death did his contributions entirely cease. Even Mrs. Carey’s memory yielded up a fine reel, the “Absent-minded Woman,” which her husband did not play.

In the course of time, enthusiasts on the subject were frequent visitors to Brighton Park, the Mecca of all who enjoyed traditional Irish music. They came to hear James O’Neill play the grand old music of Erin which had been assiduously gathered from all available sources for years, and, pleased with the liberality displayed in giving everything so acquired circulation and publicity, they cheerfully entered into the spirit of the enterprise and contributed any music in their possession which was desired. Many pleasant evenings were thus spent, and those who enjoyed them will remember the occasions as among the most delightful of their lives.

To speak in praise of the ability of one whose work in the arrangement of our collections should speak for itself, may be a violation of conventional ethics; yet I may be permitted to say that on more than one occasion, and without preparation, he has filled a place in an orchestra in the absence of a regular member, and that in rendering Irish airs on the violin he is so far without a successful rival.

Sergeant James Early, a very good Irish piper, and his friend, John McFadden, a phenomenal fiddler, both inheriting the music of David Quinn, the sergeant’s instructor, posessed almost inexhaustible stores of traditional tunes. All that his admirer, James Kennedy, told me of McFadden’s excellence, was more than realized. The best of them were inclined to take off their hat to “Mack,” as he was familiarly called. Everything connected with his playing was original and defiant of all rules of modern musical ethics; yet the crispness of tone and rhythmic swing of his music were so thrilling that all other sentiments were stifled by admiration.

He came of a musical family, and it is quite certain that his attainments were due more to heredity than to training; but it does not appear that any connection existed, except the identity of surname, between the McFaddens of Mayo and the musical McFaddens of Rathfriland, County Down, from whom Dr. Hudson, editor of The Dublin Monthly Magazine, obtained some rare Irish melodies.

During successive years, strains almost forgotten kept coming from their stimulated memories and were deftly placed in score by our scribe, O’Neill. “Old Man” Quinn, as he was affectionately called, belonged to the Connacht school of pipers and had great renown as a jig player. He was much given to adding variations to his tunes, according to the custom of his time. As a wit he had a keen sense of the ridiculous, and his unlimited fund of humorous and oftentimes grotesque anecdotes derived from personal experience is even now as well remembered as his music. One frequently quoted was the case of a conceited fellow whose execution on the pipes was far from perfect. Fishing for compliments, he remarked to Mr. Quinn one day, “Most people say I’m the best piper in this part of the country, but I don’t think myself that I am.” “Faith, it is you I believe,” was the old man’s candid but uncomplimentary reply.

Not the least prolific of our contributors was Patrolman John Ennis, a native of County Kildare, who was both a fluter and a piper. His tunes were, as a rule, choice and tasty, and his interest in the success of our hobby was displayed in a curious way. Suspecting that several pet tunes were withheld from us by a couple of good players, he conceived the scheme of ingratiating himself with the musicians. Affecting unconcern, he contrived to memorize the treasured tunes, and then had them promptly transferred to James O’Neill’s notebook. To him we are indebted for many good tunes, among them being the following: “Young Tom Ennis,” “Bessy Murphy,” “Ask My Father,” “Child of My Heart,” and “Will You Come Down to Limerick” - jigs; “Toss the Feathers,” “Jennie Pippin,” “Miss Monaghan,” “Kitty Losty,” “Trim the Velvet,” “The Dogs Among the Bushes,” “The Sligo Chorus,” “College Grove,” “Over the Bridge to Peggy,” and the “Reel of Bogie.” Two excellent hornpipes, “The Kildare Fancy” and “The Wicklow Hornpipe,” were also contributed by Ennis. None of the above dance tunes, so far as the writer is aware, has ever been published in an Irish collection.

John Ennis was also a good entertainer, and many a Sunday afternoon was pleasantly passed at his hospitable home by a coterie of kindred spirits in those years. Besides, he possessed literary ability of no mean order, and contributed some able and interesting article on Irish music and dances to the press from time to time. His son Tom displays much musical talent and bids fair to rank high as an Irish piper.

“The Garden of Daisies,” a famous set dance, was known to us all by name alone, and we had almost despaired of obtaining a setting of it, when, to our joy, we learned that O’Neill’s next-door neighbor, Sergeant Michael Hartnett know the tune as it was played where he lived. It varied but little from an air I heard my father sing. The old saying, “It never rains but it pours.” was well exemplified in this case. While enjoying a steamboat excursion on the Drainage Canal a week or so later, what should I hear on the boat but another version of our long-lost tune, played in fine style by Early and McFadden! It had been sent them by Pat Touhey, who learned it from a fiddler recently arrived in Boston, and who in turn had picked it up from Stephenson, the great Kerry piper. The latter, whose execution on the Irish or Union pipes was remarkable, once accompanied Ludwig, the celebrated baritone, on one of his American tours. Two inferior versions of this tune have since appeared in Petrie’s Complete Collection of Irish Music. The Stephenson setting, in O’Neill’s Music of Ireland, is much to be preferred.

Another favorite, well known by name as “The Fox Chase,” was obtained from the same source, and although I have since heard played and also found among the Hudson manuscripts other versions of it, none equals Stephenson’s setting, which fills fifteen staffs.

According to Grattan Flood, “The Fox Chase” was composed by a famous Munster piper named Edward Keating Hyland, who had studied theory and harmony under Sir John Stevenson. He won the royal favor on the occasion of George the Fourth’s visit to Dublin in 1821, and was rewarded with the King’s order for a fifty-guinea set of pipes in appreciation of his fine performance.

In a large work entitled Ireland, by Mr. And Mrs. S. C. Hall, published about 1840, this composition is mentioned in connection with Gandsey, the “king of Kerry pipers.” “To hear him play,” they say, “was one of the richest and rarest treats of Killarney. Gandsey is old and blind, yet a finer or more expressive countenance we have rarely seen. His manners are, moreover, comparatively speaking, those of a gentleman. For many years he was the inmate of Lord Headley’s mansion, and was known universally as `Lord Headley’s piper.’ It would be difficult to find anywhere a means of enjoyment to surpass the music of Gandsey’s pipes. No one who visits the lakes most omit to send for him. Those who return without hearing him will have lost half the attractions of Killarney. Above all, he must be required to play `The Mothereen Rue’ or `The Hunting of the Red Fox.’ It is the most exciting tune we have ever heard, and exhibits the power of the Irish pipes in a manner of which we had previously had no conception. It is of considerable length, beginning with the first sight of the fox stealing the farmer’s goose; passing through all the varied incidents of the chase - imitating the blowing of the horns, the calling of the hunters, the baying of the hounds, and terminates with ‘the death’ and the loud shouts over the victim. Gandsey accompanies the instrument with a sort of recitative which he introduces occasionally, commencing with a dialogue between the farmer and the fox, -

“ `Good morrow, fox.’ `Good morrow, sir.’

`Pray, fox, what are you ating?’

`A fine fat goose I stole from you,

Sir, will you come here and taste it?’

This celebrated musician, who died in 1857, when ninety years old, was the son of an English soldier who won the love of a Killarney colleen and settled down in that romantic spot.

The following story, told me years ago in Chicago by a Kerryman, may be found not uninteresting:

An indifferent strolling piper happened along one day, and, after listening to Gandsey’s music for a while, was induced to play a few tunes himself. The poorest performance rarely fails to evoke some recognition from an Irish audience, so the kindly Gandsey remarked, “Ni holc a sinn,” (”That’s not bad”). Not to be outdone in politeness, the stranger generously replied, “Ni holc tusa fein a Gandsey” (”You’re not bad yourself, Gandsey”).

Our placid neighbor, Sergeant Hartnett, born among the glens in northwest Cork, proved to be a rare “find.” An excellent dancer of the Munster school, he remembered many old dance tunes beside “The Garden of Daisies,” such as “The Ace and Deuce of Pipering,” etc., as well as strange and haunting plaintive airs. What could be more characteristic in traditional Irish music than “The . Fun at Donnybrook”? The text recited in Irish what a stranger saw at that noted fair, and of course the rhyming narrative extended to more than a dozen verses. This strain so charmed our kind and appreciative friend, Rev. Dr. Henebry, while on a visit to our city, that it was not without much persuasion he could be induced to lay down his violin, although dinner awaited him.

Rumors were afloat to the effect that a youthful prodigy on the fiddle lived somewhere in “Canaryville,” a nicknamed settlement in the Stock Yards district. When located he proved to be a modest, good-looking young fellow, apparently about seventeen years old, named George West. Prosperity evidently overlooked him in the distribution of her favors; in fact, he had no fiddle. The five-dollar “Strad’, his widowed mother bought him before she died had been crunched beyond repair by over two hundred pounds of femininity which inadvertently landed on its frame. A trip to Brighten Park demonstrated that his reputation had not been exaggerated. He was a wonder, all right, for his age, and a credit to any age. Such a bow hand and such facility in graces, trills and triplets, were indeed rare. ‘Twas a revelation, truly, and it was little wonder that admiration of his gift was succeeded by jealousy occasionally. Everything was done to place him in some pleasant and profitable position. Work, however, was not to his taste. Ambition along that line held no lures for him. One solitary talent he possessed, and that uncultivated. Two lessons, aside from hearing and watching James Kennedy play, constituted his only musical training, yet he could memorize and play offhand any dance tune within a few minutes. I recollect one occasion when he picked up four from me in less than half an hour. Three good tunes were taken down from his playing - two double jigs, “The Boys of Ballinamore” and “The Miller of Glanmire,” and a hornpipe called “The Boys of Bluehill.” This latter tune, which West heard from a strolling fiddler named O’Brien, was entirely new to our Chicago musicians.

One evening I accompanied him to make the acquaintance of his friend O’Malley, who eked out a living by playing at house dances. A trip through a few dark passageways and up a rickety back stairs led us to his apartments. There was welcome for West, but his introduction of me as Captain of Police was very coldly received. With evident reluctance, O’Malley produced the fiddle, on West’s request, while his wife and children viewed me as an interloper, with unconcealed misgiving. Calling the children to me in a friendly way, and giving them some coin, effected a sudden change in the atmosphere. Beer soon appeared on the table, and under its mollifying influence all indications of suspicion and distrust quickly disappeared. O’MalIey, though handicapped with the loss of one finger from his left hand, played “like a house on fire” as long as we wanted to listen. His rapid yet correct execution was astonishing under the circumstances, but I learned afterwards that he was seldom capable of handling the bow after midnight if any kind of intoxicating liquor was within reach. In such emergencies, his understudy, Georgie West, completed the engagement. Thus lived the careless, improvident but talented Georgie, until an incident in his life rendered a trip to the far west advisable.

Attracted by the growing popularity of Brighton Park as a rendezvous for Irish music “cranks,” and the publicity given to our meetings by the press, the number of visitors constantly increased. Among them were such desirables as Sergeants James Kerwin, James Cahill, Gerald Stark and Garrett Stack; also Patrolmen Timothy Dillon, William Walsh and John P. Ryan.

Sergeant Cahill, unassuming as he was, possessed many quaint tunes from the County Kildare, where he was born, and besides being an Irish piper, he was an expert woodturner. In a shop in the basement of his residence he made many chanters fully equal to TayIor’s work in tone and finish. Even as a reed-maker he had few equals, and what was still better, his liberality and assistance were never appealed to in vain.

Mr. Dillon, a veteran violinist and officer of the law, hailed from County Kerry, and any one at all acquainted with Irish geography and tradition knows what to expect of him. His tones and trills, weird as the banshee’s wailing, realized the cherished ideals of our enthusiastic champion of traditional Irish music, the Rev. Dr. Henebry.

“Big” John Ryan, once champion “stone-thrower,” and an amateur on several musical instruments, gave us the inimitable “Raking Paudheen Rue” and “The Fair Maid of Cavan” although he hails from historic Tramore, County Waterford.

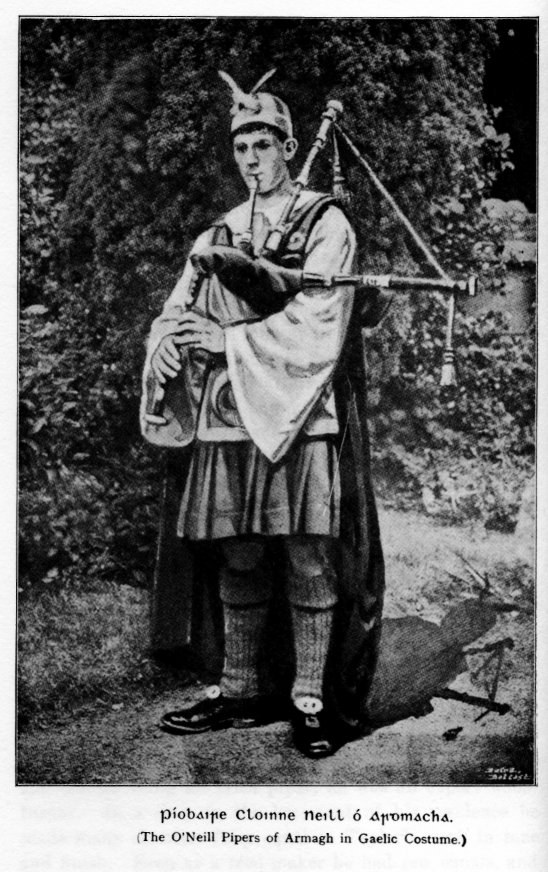

“Willy” Walsh, a native of Connemara, County Galway, was and is a rare musical genius. Self-taught from printed music appropriate to the instrument, he became an accomplished “Highland” piper and toured the country with Sells Brothers’ circus one season. He next turned his attention to the fiddle, but wind instruments being more to his liking, he chose the flute, on which difficult keyed instrument he became quite expert. For his own personal use he has compiled a large volume of selections, principally from O’Neill’s Music of Ireland, but transposed to the Highland pipe scale, which, by the way, differs from that of all other musical instruments. Just a score of Irish tunes transcribed by him were forwarded to Francis Joseph Bigger, of Belfast, Ireland, in 1908, for the use of a band called “The O’Neill Pipers of Armagh.”

In acknowledging the receipt of those prized tunes and marches, Mr. Bigger informed me that they were “just what were wanted,” and he expressed the hope that we would favor “The O’Neill Pipers of Armagh” with more of them.

No words of mine could do justice to Sergeant Kerwin - the genial, hospitable “Jim” Kerwin, not as a fluter and a lover of the music of his ancestors, but as a host at his magnificent private residence on Wabash Avenue. On his invitation and that of his equally hospitable and charming wife, a select company, attracted and united by a common hobby, met monthly on Sunday afternoons at his house for years. They were all good fellows, unhampered by programme or formality. Pipers, fiddlers and fluters galore, with a galaxy of nimble dancers and an abundance of sweet-voiced singers, furnished diversified entertainment the like of which was never known on the shores of Lake Michigan before nor, unfortunately, since; but of this, more anon. “There is an emanation from the heart in genuine hospitality which cannot be described,” says Washington Irving, “but is immediately felt, and puts the stranger at once at his ease”; and so it was at Kerwin’s.

Not by any means the least distinguished of our number was Adam Tobin, a Kilkenny man, equally proficient as a piper or fiddler. Ordinarily genial and accommodating he was easily aroused by opposition; yet he was universally popular, and year after year he has been engaged by one of the Scotch societies to play at their picnics. His repertory of tunes was both choice and extensive, and I am inclined to believe that a few of them escaped the vigilance of our scribe, Sergeant O’Neill.

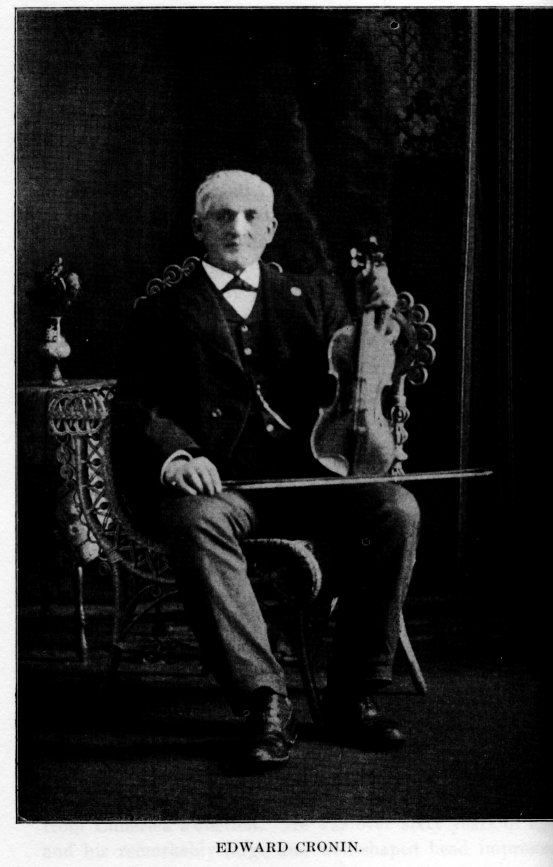

The discovery of a new musical star of uncommon brilliancy by John McFadden, when announced, natural aroused keen curiosity. When seen and heard at a select gathering at Lake View, a distant part of the city, the wonder was how an Irish violinist of such exceptional ability could have remained unknown to us all these years.

The new star was Edward Cronin, a Tipperary man from Limerick Junction. He was over sixty years of age, and his remarkably large and well-shaped head impressed one as being the seat of rare intellect. His features, set and expressionless as the Sphynx when playing, relaxed into genial smiles in conversation at other times. Long, sweeping bowing, with its attendant slurs, gave marked individuality to his style which was both airy and graceful. In fact, he represented a distinct school in this respect, for among traditional Irish musicians nothing is so noticeable as the absence of uniformity of style or system. The pages of Grattan Flood’s History of Irish Music afford us an insight to the causes which led to this result. When harpers and pipers were indiscriminately imprisoned by order of the government, Irish National Schools of Music could not be expected to prosper. Scotland had a College of Pipers, and still has schools of pipering, with an abundance of printed pipe music and books of instruction. The Irish aspirant for musical honors, outside of a few of the large cities, must learn as best he can from any one within reach who is willing or able to teach.

Returning to our friend Cronin, he was a mine of long-forgotten melody. Old tunes, some of them known to us by name only, he could reel off by the hour. Lacking congenial companionship, many of his traditional treasures were but faintly remembered; yet intercourse with music lovers gradually unlocked his memory until Irish Folk Music was enriched by scores of tunes through his instrumentality. They were all committed to the art preservative by our scribe, and it was fortunate for many reasons that such action was taken, one of which is that the majority of them entirely escaped the painstaking efforts of Dr. Petrie and Dr. Joyce.

Plucked from obscurity, Mr. Cronin became all at once famous and popular, and played at numerous public and private entertainments. As he was capable of writing music, this accomplishment enabled him to aid us materially by noting down the tunes of others, as well as his own. Scoring down ancient and composing new music became with him an absorbing passion, after many years of corroding apathy; but as Addison says, “Music is the only sensual gratification which mankind may indulge in to excess without injury to their moral or religious feelings.”

“Music has power to melt the soul,

By beauty Nature‘s swayed;

Each can the universe control,

Without the other‘s aid.

But when together both appear,

And force united try;

Music enchants the list’ning ear,

And beauty charms the eye.”