CHAPTER V

STORIES OF TUNES WITH A HISTORY

DANCE MUSIC

“God’s Blessing be on you, old Erin,

Our own land of frolic and fun;

For all sorts of mirth and diversion,

Your like was not under the sun.

Bohemia may boast of her polka,

And Spain of her waltzes talk big;

Sure they’re all nothing but limping,

Compared with our old Irish Jig.”

THE classification of Irish melodies is to a certain extent arbitrary, as dance tunes are not infrequently used as airs for songs and marches, and vice versa.

Among the thousands of Irish melodies which have survived through centuries of adversity, the dance tunes are relatively few. The strains of the older airs and marches from which they have been evolved are plainly traceable in much of the popular Irish dance music of the present day. Even the most rapid Irish tune, when played in slow time, will be found to contain some lurking shade of pathos, and even to possess something of that melancholy luxury of sound which characterizes our most ancient melodies.

Not every tune has a story which would justify its telling in this article, therefore only those about which something is known likely to interest the average reader, will receive more than casual mention.

When Edward Cronin, an excellent fiddler of the traditional school, was brought into the limelight from obscurity, little did we suspect the wealth of rare folk music which lay stored in his retentive memory. Generous as the sunlight, he dictated without hesitation musical treasures known only to himself. In every variety of dance music he was a liberal and prolific contributor, and not only that, but a capable reader and writer of music also.

No double jig ever introduced in Chicago met with such immediate popularity among musicians and dancers as “Shandon Bells.” Mr. Cronin learned it in his youth at Limerick Junction, Tipperary, but it was entirely unknown, it seems, except in that locality. It has also been called “Punch for the Ladies” and “Ronayne’s Jig,” I learned during our investigations.

“Hartigan’s Fancy,” “The Walls of Liscarroll,” “The Pipe on the Hob,” “Guiry’s Favorite,” “Castletown Conners,” “Martin’s One-horned Cow,” “The Foot of the Mountain” and the “Maids of Ballinacarty,” all unpublished tunes and new to us, were obtained from John Carey, a native of Limerick, who died at an advanced age since then. Another jig which he called the “Jolly Corkonian” is the original of the march which the Scotch call “The Hills of Glenorchy.” In Dr. Joyce’s recently published work, Old Irish Folk Music and Songs, the jig named “Green Sleeves” is a variant of “Hartigan’s Fancy,” while “The House of Clonelphin” is Carey’s “Jolly Corkonian,” and so is “Mrs. Martin’s Favorite” as well.

“Kitty’s Rambles,” or “The Rambles of Kitty,” is by no means a new tune, but my setting of it with four strains instead of two deserves special mention. In a simpler form it was also known as “Dan the Cobbler” and “The Lady’s Triumph.” A setting of it in two strains is to be found in Dr. Joyce’s Old Irish Folk Music and Songs, entitled “I’m a man in myself like Oliver’s Bull.”

“Doctor O’Neill” and “The King of the Pipers” created a sensation when first introduced by Mr. Cronin. None among his audience had heard them before. Each tune consisted of five strains and it is quite probable that they had originally been clan marches. As nothing resembling those ancient tunes have been encountered in our researches, we are fortunate in being the means of their preservation. Insipid settings of the “Templehouse Jig” have heretofore been printed in America, but none to compare with Mr. Cronin’s version, which is the real thing from the glens. Another of his good ones is “Banish Misfortune,” a version in three strains, which is much superior to the two-strain setting in the Petrie Collection.

Once when he was playing a characteristic old Irish jig then heard for the first time by his audience, Sergt. Early remarked with evident appreciation, “Ah, that’s well covered with moss” - alluding to its ancient strains. Its original title being unknown even to Mr. Cronin, it was promptly christened “All Covered with Moss.” This jig is printed as an unpublished tune under the name “Roger the Weaver” in Dr. Joyce’s Old Irish Folk Music and Songs, just out of press.

After years of playing since our first acquaintance and at a time when his dormant repertory was supposed to be exhausted, an unfamiliar jig tune caught my ear. “Everything comes to him who waits,” thought I, when Mr. Cronin told us the tune was known to the oldtimers as “O’Sullivan’s March.” This name had been met with in my studies, but nothing purporting to be the air in question was ever discovered until recently, when it was found printed in Lynch’s Melodies of Ireland, published in 1845. The arrangement is unattractive in that volume and much inferior to Mr. Cronin’s version. In its present form, like many original marches, it is a jig and printed as such in the Dance Music of Ireland. The identity of the name “O’Sullivan’s March” alone appears to have been lost, for the strains may be recognized as resembling those of the “Old Woman tossed up in an blanket seventeen times as high as the moon,” a very ancient Folk Song.

“The Gold Ring,” one of Pat Touhey’s favorite jigs, came to us through John Ennis. It consists of seven strains, although the “Pharroh or War March” from which it has been evolved contains nine. Bunting states that the latter is “Very ancient - author and date unknown.” Other excellent traditional double jigs contributed by Ennis are “Malowney’s Wife,” “Bessy Murphy” and “Nancy Hynes. A version of the latter as Maire ni h-Eiden is printed in the Petrie Collection.

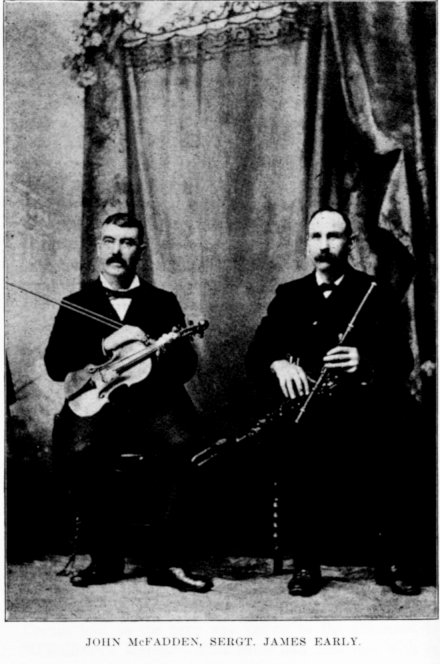

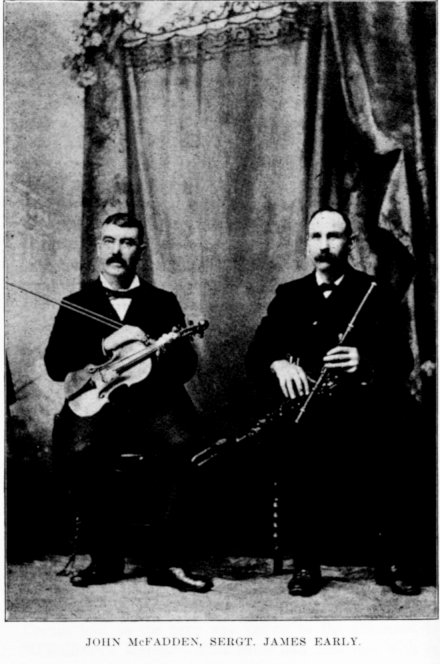

In all matters relating to music, Sergt. James Early and John McFadden are inseparable. They are natives of adjoining counties in the province of Connacht and, aside from their long association with the noted Irish piper, David Quinn, from the same province, who died in this city at an advanced age in 1888, they have played together in public and private for so many years that they have come to be regarded as a musical unit.

Nowhere in Chicago are Irish musicians, whether old residents or new arrivals, more welcome than in Sergeant Early’s hospitable home. Centrally located, it had been at all times and still is a meeting place for a choice circle of music-lovers, and no one has been so unselfishly and unobtrusively helpful in all that relates to the well-being of new comers and strangers as the resourceful sergeant himself.

That a vein of subdued sadness pervades our animated measures as well as our slow airs is well exemplified in “The Cook in the Kitchen” and “Cailleach an t-airgid,” or “The Hag with the Money.” Those plaintive jigs contributed by Early and McFadden are not included in any previous collection of Irish music. Even the indefatigable Dr. Petrie missed them.

Among the many florid and varied settings of jigs popular in bygone years is “Galway Tom” in five strains. In O’Farrell’s Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, volume 3, published in 1804, we find a different setting of “Galloway Tom” (as it is given) but with four strains. In pencil some former owner of this rare volume noted phonetically “Boughaleen Buee” after the English name. Similar notes over other tunes evinced a creditable knowledge of the subject on the part of the critic. An air entitled An Buacaillin buidhe, in common time, in the Petrie collections bears no resemblance to either version of “Galway Tom” above mentioned. Many other fine double jigs were obtained from Early and McFadden, such as “The Piper’s Picnic,” “Saddle the Pony,” “I Know What You Like,” “Sergt. Early’s Dream,” “Stagger the Buck,” “Scatter the Mud,” “The Miners of Wicklow,” “The Man in the Moon” and “The Queen of the Fair.” In Bunting’s third volume, The Ancient Music of Ireland, “The Miners of Wicklow” is included as an air. Dance versions of it, however, were printed in Aird’s Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, 1782, and in McGoun’s Repository of Scots and Irish Airs, circa 1800.

“The Queen of the Fair,” a composition of uncommon excellence by by the adroit and versatile Mac. himself, gives an idea of the originality and talent possesed not by him alone but others such as James O’Neill and Edward Cronin, who under more favorable circumstances would be not unknown to fame in the world of music.

No one contributed more to the success of the efforts of the American Irish of Chicago to preserve and perpetuate the music of the Emerald Isle than our scribe, Sergeant James O’Neill himself. Tireless and patient in noting down vagrant strains from others, often traveling long distances for the purpose, he also possessed treasures in his father’s manuscripts and his own memory. Those he arranged according to his personal judgment, consequently the writer knows little of any stories connected with most of them. Not the least appreciated was the unfailing welcome and hospitality which made his home the Mecca for all interested in Irish music. Some came to increase our aggregation of melodies, while others came only to enjoy good music or learn tunes new to them and not elsewhere obtainable. All were equally welcome, and the “Evenings at O’Neill’s” were among the most enjoyable of our lives.

The story of that splendid double jig, “The Old Grey Goose,” is exceptional and not uninteresting. One of the tunes picked up by the writer from John Hicks, the great Irish piper before mentioned, consisted of the first and third strains of our printed setting. Many years later I heard James Kennedy, a fine fiddler from County Leitrim, play another version of it, being the first and second strains of our tune, which he called “The Geese in the Bog.” While noting down from my dictation the three strains referred to, Sergt. O’Neill’s memory was aroused to the fact that he had a version of this jig among his father’s manuscripts. A slight rearrangement resulted in a jig with six distinct strains which will compare favorably with any tune of that class in existence. But about the name -a different jig known to a limited extent and printed in an American publication was called “The Geese in the Bogs.” A somewhat similar tune under the same name is also printed in the Petrie collections. Even though Kennedy was possibly right, and there be some who say he was, a change of name was deemed advisable. To preserve to some extent the connection of the historic and popular fowl with our prize, it was christened “The Old Grey Goose.” In O’Farrell’s National Irish Music for the Union Pipes, published in 1797-1800, a version of it resembling Kennedy’s is printed under the name “We’ll all Take a Coach and Trip it Away.” To add to the confusion D’arcy McGee has written a song for the melody entitled “I would not give my Irish wife for all the dames of Saxon land.” A variant of our jig and named “The Rakes of Kinsale,” can be found in Dr. Joyce’s new work, Old Irish Folk Music and Songs. It has but four strains, one of them being a duplicate of the first an octave higher.

So much for the perplexities incidental to the study and collection of Irish Folk Music at this late day.

“Doherty’s Fancy,” a jig so named for the musician from whom Sergeant O’Neill learned it, is a characteristic Ulster tune. It differs noticeably in its decisive ringing tones from the soft and affecting plaintiveness of the tunes belonging to the West and South of Ireland.

Less distinct is “Wellington’s Advance,” a jig or march unknown in the Southern provinces.

Few names are more universally known than “Morgan Rattler,” yet few tunes are more rare. In Aird’s Selection of Scotch, Irish, English and Foreign Airs, Vol. 3, 1788, the tune appears as “Jackson’s Bouner Bougher” (whatever that may mean) and consists of but two strains. Jackson was a famous Irish piper and fiddler, who composed enough dance tunes, mostly jigs, to fill a volume, which actually appeared in 1774 as Jackson’s Celebrated Tunes. His name, almost invariably connected with the titles of his compositions, indicated their origin, although in course of time many of them came to be known by other titles. Elsewhere in Aird’s Selection, etc., etc., “The Morgan Rattler” in four strains meets the eye. This identical version is to be found in McGoun’s Repository of Scots and Irish Airs, before alluded to, and in McFadyen’s Selection, etc., etc., printed in 1797. “Morgan Rattler,” with three strains, is included in the contents of Wilson’s Companion to the Ballroom, published in London in 1816.

Sergeant O’Neill’s setting, copied from his father’s music books, is much superior to all, having been embellished by a skillful hand, according to the custom prevailing a century ago, until a total of ten strains display his versatility.

Many fine dance tunes came into our collection through the liberality of John Gillan, a retired business man, whose interest in Irish music and musicians has been perhaps the leading feature of his life. Among his manuscripts formerly in the possession of prominent musicians in Longford, his native country, and the adjoining county of Leitrim, were several elaborate settings of very ancient tunes, such as “Biddy Maloney,” a double jig of seven strains. Another unpublished jig is one named by us, “Gillan’s Apples.” On the manuscript it was called “Apples in Winter,” but as another jig of that name was to be found already published a slight change was made in the title to avoid confusion. The two first strains of this tune were played by John Hicks. Whoever added the two additional strains was no novice in composition.

“Paudeen O’Rafferty,” or “Paddy O’Rafferty,” as Bunting calls it, is another of those ancient tunes which has been the subject of embellishments or variations about the end of the eighteenth century. It is said to have been composed by O’Carolan in honor of a little boy of that name who won immortality by obligingly opening the gate for the bard while paying a visit to his first love, Bridget Cruse.

What is probably the original setting in two strains was printed in Aird’s Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol. 3, 1789, as “Paddeen O’Rafardie, Irish.” Bunting’s version, which he obtained in County Antrim in 1795, and printed in 1840, consists of five strains, but the author and date of composition he notes are unknown.

Our setting of that rare old jig, “Cherish the Ladies,” in six strains, was obtained from the Gillan manuscripts. Versions of it in three strains are to be found in the Petrie and Ryan collections. Dr. Petrie refers to it as a Munster jig, yet none who the writer heard play it in any style were natives of that province. In its original form of two strains it was one of Jackson’s jigs, and Dr. Petrie’s opinion receives corroboration by finding a simple version of the tune in Dr. Joyce’s Old Irish Folk Airs and Songs, just published.

“Be Easy, You Rogue,” which is a free translation of the Irish title, “Stadh a Rogaire Stadh!” also from the Gillan manuscripts, is a florid setting of an old jig or march in four strains. Its relationship to “The Priest with the Collar” in the Petrie collections is plainly evident. “The Monaghan Jig” is another of Mr. Gillan’s contributions, but “Katie’s Fancy” has the most interesting history of any.

Peter Kennedy, a farmer living near Ballinamore, County Leitrim, and a fiddler of more than local reputation, from whom Mr. Gillan obtained this tune, told in an amused way how he had followed a fluter around the streets of that town in order to learn a new jig he was playing. Failing to memorize it to his satisfaction, Kennedy was obliged to trace out the fluter’s lodgings and pay four pence for his services in dictating “Katie’s Fancy,” as he called it to his visitor. The tune was regarded by Mr. Gillan as a rare prize, and he safely guarded it on his return to Chicago. Miss Nellie, his daughter, with her characteristic good nature, surreptitiously wrote me a copy. As soon as I could whistle it, the jig was given general circulation.

The mention of her name suggests this as an auspicious opportunity to say that Miss Gillan is a pianist of rare accomplishment and phenomenal execution. It is entirely beyond the descriptive powers of the writer to do her justice in this respect. In the playing of Irish dance music of all varieties she was simply in a class by herself.

Perhaps no dance tune of such marked individuality as the “Lark in the Morning” can be found in the whole range of Irish music. It was furnished us through Sergeant Early from an Edison record made by James Carbray in Quebec, Canada. Nothing but hearing it played, on the violin particularly, would give an adequate idea of its originality and beauty. Mr. Carbray, now a resident of Chicago, tells us he picked up the tune from a Kerry fiddler named Courtney. Nothing even suggestive of this rare strain has been encountered in our researches, but I have a recollection of hearing it alluded to as an old Set-Dance.

Other tunes sent us on Edison records by Mr. Carbray were a double jig named “Courtney’s Favorite” and a single jig, which for want of a title, we named “Carbray’s Frolics.” Since the publication of O’Neill’s Music of Ireland Mr. Carbray has become a resident of Chicago, and, being an excellent musician and maker of musical instruments, as well as a kindly, courteous gentleman, it goes without saying that his welcome was warm and his companionship appreciated.

We are all more or less indebted to Bernard Delaney for the introduction of many fine tunes to our community. His well deserved reputation as an Irish piper did much to spread the knowledge of his music among local musicians, as well as to promote the popularity of Irish music in general. To give him due credit at this date in that respect would be no easy task for much that was noted down by Sergeant O'Neill from the dictation of others was no doubt memorized from Delaney's playing. As a matter of fact, his repertory was so comprehensive and his memory so retentive that discrimination is now almost out of the question. Like all pipers of our acquaintance, he entertained a decided preference for reels. So fertile in imagination and deft in execution was he, as well as Patrick Touhey, that their graces, trills and deviations were endless in variety. While their style and skill entranced the listener, both were the despair of the music writer.

It was Bernard Delaney, I believe, who introduced to the Chicago pipers and fiddlers an unpublished jig of rare traditional flavor known as “An Bean Do Bhi Ceadna Agam,” or “My Former Wife.” The sudden popularity which it achieved became a source of no little embarrassment to its sponsor. It was one of the “pet” jigs which he liked to play at public entertainments. When Early and McFadden happened to be on the same programme and came on the stage ahead of Delaney, the mischievous pair never failed to play his favorite tune.

Incidents of this nature influence not a few good musicians to keep from circulation their best tunes, and which they do not choose to remember except on special occasions. What can be more amusing, if not provoking, than to hear a fine performer roll out a string of “chestnuts” to the exclusion of all rare tunes when one understands the motive for this tantalizing practice?

Being an audience of one, on a certain occasion in the home of one of our most eminent pipers, he, seeing no necessity for restraint, played in grand style half a dozen reels and jigs entirely new to me, although we had been more than intimate friends for years. Very civilly he agreed to give us the tunes whenever Sergeant O’Neill was prepared to note them down. Together we called a few evenings later ready for business, but, alas - in the meantime our piper’s memory had suffered a relapse, and neither name nor suggestion could arouse it. He couldn’t remember any of the tunes, and, judging from prior experience, I am inclined to believe that, like others formerly heard from his facile fingers, those tunes are forgotten in real earnest now.

One of Delaney’s best jigs was the “Frieze Breeches,” which in some form is known all throughout Munster. A strain remembered from my mother’s singing of it was added to Delaney’s version, making a total of six in our printed setting. A ridiculous, although typical, folk song, called “I Buried My Wife and Danced on Top of Her,” used to be sung to this air, which bears a close resemblance to our version of “O’Gallagher’s Frolics.”

Dr. Joyce in his new and most important work prints two versions of “Gallagher’s Frolic” as unpublished tunes, and unconsciously perhaps a third version under the name, “Breestheen Mira.” This latter title, it will be observed, preserves the word “Breestheen” or “Breeches” as in the name of our tune.

Another great favorite of Delaney’s was the “Rakes of Clonmel,” which the writer memorized and dictated to our scribe. The latter, remembering a third strain from an Ulster setting, called the “Boys of the Lough,” annexed it.

How certain airs and strains more or less diversified can be traced all over Ireland is indeed remarkable, while others plainly traditional remained unknown beyond a limited district in which they apparently had originated.

The following instance well illustrates this limitation: Abram Sweetman Beamish, of Chicago, from whom we obtained the Buachaillin Ban, or the “Fairhaired Boy,” “My Darling Asleep,” and the “Knee-buckle” jigs, also the “Skibbereen Lasses,” “Tie the Bonnet,” “Dandy Denny Cronin” and the “Humors of Schull” reels, was a native of a parish adjoining the parish of Caheragh, in which the writer was born. Our ages are equal and we left Ireland about the same time, yet I never heard in my youth any of the tunes above named. The first and fifth only were known to the local musicians. Similarly most of my tunes were unfamiliar to Mr. Beamish.

Such is its decadence now in that part of Ireland that none of the rising generation, including amateur musicians, have any but the most fragmentary knowledge of the wealth of Folk Music in common circulation fifty years ago.

Through Edward Cronin’s efforts we obtained from John Mulvihill, a native of Limerick, an unpublished jig named the “Stolen Purse,” which in its quaint tonality indicates its evolution from some traditional lament. A good reel, named “Bunker Hill,” was also noted from his playing. The name was suspiciously modern, but upon investigation I find that Bunker Hill is Dr. Henebry’s address in or near the city of Waterford, Ireland. Were the writer to tell what is remembered of his personal experiences and contributions, being naturally familiar with a mass of details, the reader would be justified in thinking that personality was being given entirely too much prominence in those notes. Such is not the intention, however, because the constant aim has been to confine those discursive sketches within the narrowest possible limits.

The avoidance of duplicates, and the inclusion of all that deserved a place in our collections, has at all times been the subject of our greatest concern, still with all our care in the vast amount of material to be considered, complete success has not been attained. One of my earliest boyhood recollections was an air or jig called “Get Up Old Woman and Shake Yourself,” which, by the way, is not to be confounded with “Go to the Devil and Shake Yourself,” although it has been so misnamed in Alday’s Pocket Volume of Airs, Duets, Songs, Marches, etc., Dublin, 1800, and in Haverty’s Three Hundred Irish Airs, published in New York in the year 1858. Neither title appears in the Bunting or Petrie collections. Under the head of Diversity of Titles this complication will be more fully discussed.

The “Humors of Bantry” is a sprightly double jig, which escaped Dr. Petrie and other collectors, although known to several of our musicians in a simpler form than our setting, which has a second finish of great spirit to its second strain. “Fire on the Mountain,” the name under which Dr. Joyce prints it as an unpublished tune in his late work, Old Irish Folk Music and Songs, is also the name by which it was known to Early and McFadden, and it is also a supplementary name in the index to O’Neill’s Dance Music of Ireland.

Who has not heard of the humorous classic, “Nell Flaherty’s Drake”? But how many know the air of it? It is scored in O’Neill’s Music of Ireland, as I heard it sung in the old homestead. Fluent and melodious as it is simple, the air was never before printed. A verse of a still older song sung to it ran as follows:

“My name is Poll Doodle, I work with my needle

And if I had money ‘tis apples I’d buy;

I’d go down in the garden and stay there till morning,

And whistle for Johnny, the gooseberry boy.”

One often wonders why a popular tune passes current for years without a name among non-professional Irish musicians. Nothing is more common than to be told on making inquiry, “I never heard the name of it,” and seemingly nothing concerned them less than the name as long as they could play a tune to suit their fancy. Such was the case with the fine old traditional tune, the “Merry Old Woman.” None of our best performers had any name for this favorite jig, so it could not be permitted to remain nameless any longer. By dint of persistent investigation we eventually learned that it was known as the “Walls of Enniscorthy.” Few double jigs equal it. None excel it, and I’m inclined to believe that it is one of “Old Man” Quinn’s tunes preserved to us by Sergeant Early. A variant of this jig I find appears in Dr. Joyce’s late work under the name, “Rakes of Newcastle-West,” but in a much simpler setting.

While traveling on post, one summer evening in 1875, the strains of a fiddle coming through the shutters of an old dilapidated house on Cologne street attracted my attention. The musician was an old man named Dillon, who lived alone, and whom I had seen daily wielding a long-handled shovel on the streets. His only solace in his solitary life besides his “dhudeen” was “Jenny,” as he affectionately called his fiddle. A most captivating jig memorized from his playing I named “Old Man Dillon” in his honor. Like many others of his tunes, it was nameless. Inferior versions of it have since been found, entitled “A Mug of Brown Ale,” and I am satisfied this is the original and correct name. J

It is a curious coincidence in our experience that all solitary musicians - that is those who play for their own enjoyment mainly - seldom vary from song or marching time in the execution of dance music.

A fine old traditional tune, “Drive the Cows Home,” although classed as a double jig, was evidently a clan march. William McLean, from whose piping I picked it up, played it in marching time on the Highland pipes.

To Bob Spence, a fellow boarder, in 1870, I am indebted for our setting of “Happy to Meet and Sorry to Part,” a grand and spirited double jig not found in any previous Irish collection, although printed in one American volume of miscellaneous dance music. Spence was a devoted student, and while he patiently sawed away on his fiddle, a receptive memory enabled me to learn his tune and retain it.

Another excellent jig is “The Joy of My Life,” unnamed and unpublished as far as we know. It was a favorite with Delaney, Early and McFadden, and some others.

A German bandmaster in Troy, New York, was so pleased with its rhythm that it fills a favored place in his repertoire. To impress a German leader favorably is high honor indeed for an Irish jig.

When I heard that affable Highlander, Joe Cant, play Bodach an Drantain, its Irish origin appeared indisputable, and, being a “new one,” it was retrieved as the “Grumbling Rustic,” its translated name. Incidental corroboration of its identity and my judgment came to light by finding an elaborate version of it with four variations in that extremely rare volume, McGoun’s Repository of Scots and Irish Airs, published about the year 1800. It was named “Gillan na Drover” and classed as Irish. The first and second words were plainly corrupted from the Gaelic “Giolla na” - servant or attendant of. What Irish word “drover” stands for is still a mystery. In our desperation for an intelligible title, this march in O’Neill’s Irish Music for the Piano or Violin is called “Gillan the Drover.”

The "Tailor's Wedding", which I heard played on the Highland pipes by my cherished friend, Joe Cant, had a suspiciously Irish swing to it. And so it proved to be, although printed in Scotch music books. It was known to McFadden and Early as “Skiver the Quilt,” and by that name we found it printed in both ancient and modern collection. Yet it does not appear in Petrie's Complete Collection of Irish Music.

An almost forgotten melody is the “Cailin, Deas Donn,” or “The Pretty Brown-haired Girl.” The Irish song to this air I remember only in a fragmentary way, and it is doubtful if the Folklorists have preserved a copy. Overlooked when preparing our first volume, it has been since printed in the Dance Music of Ireland. O'Farrell included it in his Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes (1810) as “Calleen Das Dawn.”

Two versions of “The Tenpenny Bit” were procured from James Kennedy and Abram S. Beamish, representing Leitrim and Cork respectively. Its existence in counties so far apart proclaims its antiquity, although no trace of it has been found in Petrie's Complete Collection of Irish Music, by that or any other name.

A willing and valued contributor to our musical stores was Timothy Dillon, a. much respected member of the Chicago police force, from which he has since been retired on pension. A violinist of the old traditional style of playing, he possessed many fine jigs and reels with which we were entirely unfamiliar, among them being “The Boy from the Mountain,” “The Woodcock,” “The Belles of Liscarroll,” “The Chorus Jig,” “Church Hill,” and “The Yellow Wattle,” double jigs; “Bothar o Huaid,” or “The Northern Road,” single jig; “Dillon’s Fancy,” “The Long Strand,” and “The Lady Behind the Boat,” reels. His style was airy and florid and quite distinct if not original in its sweeping slurs. An almost identical setting of “The Chorus Jig” is printed in Dr. Joyce’s recent work, before mentioned, as an unpublished tune. The tune of that name published by Bunting in his third collection is in two-four time and was obtained by him in 1797 from “McDonnell the Piper,” its author and date of composition being unknown. This tune is identical with “The Rocks of Cashel,” printed in other collections. An early and simple version of it under the latter name is to be found in McGoun’s Repository of Scots and Irish Airs, printed about 1800, and in Aird’s Selection of Scotch, English, Irish, and Foreign Airs, volume 4, published about 1791. In A Philosophical Survey of the South of Ireland, published in 1778, the author, Dr. Campbell, says, “We frog-blooded English dance as if the practice was not congenial to us; but here they moved as if dancing had been the business of their lives. The `Rocks of Cashel’ was a tune which seemed to inspire particular animation.”

One of the old timers is “The Three Little Drummers,” which I remember from boyhood. Dr. Petrie’s collections include three settings of it, one of them being printed without a name. Our version has three strains; the third, learned in Chicago, is identical with the second strain of Dr. Petrie’s unnamed setting. Highland pipers seldom play any other Irish jig for dancers but this, and it is to be found in most of their books or bagpipe music.

Recently I learned that “The Little House Under the Hill,” an old jig of no special merit, was composed by the famous “Piper” Jackson, who flourished about 1750. A version of it closely resembling the simple melody I learned when a boy is named “Link About” in Aird’s Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, published from 1782 to 1797. Strangely enough, the tune named “The Little House Under the Hill,” in an earlier volume of the same work, is a reel of unknown origin. The jig is also to be found in The Hibernian Muse as an air from The Poor Soldier. It was evidently in more repute a century ago than it is today, for an elaborate setting of it in eleven strains, under its proper name, was printed in O’Farrell’s Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, published in 1804.

Many years ago the writer picked up an unpublished jig from Daniel Rogers, a native of East Clare, who consoled himself for many privations and disappointments in life by merrily whistling the many rare tunes which a musical ear, had stored in his memory. He had learned it, he told me, from a County Clare fiddler named Tom Hinchy, in New York. As usual, there was no name to it, so we called it “Hinchy’s Delight.” No trace of it has been found in Petrie’s Complete Collection of Irish Music, and the only one of our local musicians who had even a variant of it was Edward Cronin.

Among the many Irish melodies interspersed throughout Mooney’s History of Ireland was one entitled “Ella Rosenberg.” It was a new one to all of us, and so enthusiastic was one of our club over its tonal beauties that it came to be known as “Father Fielding’s Favorite.” His Reverence induced the good sisters in his parish to teach it to their most promising music pupils, while he cheerfully accompanied them on the flute.

But we are not always loyal to our first love, and “Ella Rosenberg” was not the only one to feel the pangs of neglect and inconstancy. Her admirer, the musical clergyman, heard a piper named Burns play a different version of it in Waterford, while his Reverence was on one of his annual pilgrimages to Ireland. Since his return to Chicago he has been endeavoring, with poor success, to substitute the new for the old version which first captivated his fancy.

A spirited jig named the “Humors of Castle Lyons,” noted down from the writer’s dictation, is probably not a very ancient composition. It was not known, evidently, to any collectors of Irish Folk Music before Dr. Hudson obtained a setting of it from a noted piper named Sullivan, in the County of Cork, whose rivalry with Reillaghan is the subject of a story in a later chapter. The tune has found its way into American collections of harmonized melodies.

No one but an Irishman would think of naming an air or a tune “The Man Who Died and Rose Again.” Where Patrick Touhey, the famous piper, obtained this rare unpublished jig, we are unable to say.

Few tunes learned in boyhood days left such an indelible impression on my mind as “The Blooming Meadows,” which I heard Mr. Timothy Downing, a gentleman farmer at Tralibane, play in his own home. Although instructed by him on the flute, I did not venture to be too inquisitive in regard to tunes not a part of my studies, and therefore did not learn its name at that time. The melody has been previously printed under various names, but no setting has the artistic second finish to the last strain except ours. Although Dr. Joyce printed a setting of “The Blooming Meadows” in his Ancient Irish Music in 1873, a slightly different version of it, named “Trip It Along,” appears in his latest work, Old Irish Folk Music and Songs.

Other names by which this splendid double jig is known are “Down With the Tithes,” “The Humors of Milltown,” and “The Hag and Her Praskeen.” The latter was the Connacht name by which it was known to David Quinn, the celebrated piper. It has also been called “Cover the Buckle,” but I have since ascertained definitely that the name refers to a special dance and not a special tune.

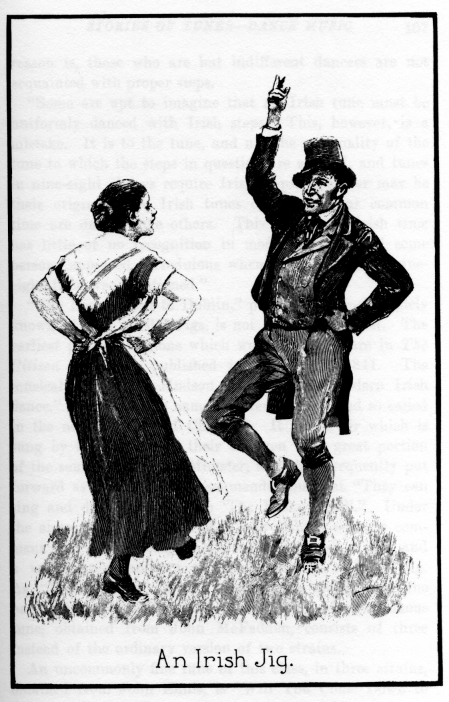

Most Irish jigs in six-eight time are “Double Jigs,” commonly termed “Doubles” in Leimster and some other parts of Ireland. Such jigs are also popularly known, at least in Munster, by the appellation of Moinin or Moneen jigs, a term derived from the Irish word moin - a bog, grassy sod, or green turf - because at the fairs, races, hurling matches, and other holiday assemblages, it was always danced on the choicest green spot or moinin that could be selected in the neighborhood. A separate classification of “Single Jigs,” and the first ever made in a printed volume, was initiated in O’Neill’s Dance Music of Ireland.

The following description of that variety is taken from The Petrie Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland, published in 1855. Like the common or “Double Jig,” the “Single Jig” is a tune in six-eight time, and having eight bars or measures in each of its two parts. But it differs from the former in this, that the bars do not generally present, as in the “Double Jig,” a succession of triplets, but rather of alternate long and short, or crochet and quaver notes. “Battering,” as applied to this variety of jig, is called “single battering.” The floor is struck only twice - once by the foot on which the body leans, and once by the foot thrown forward.

In considering Hop Jigs or Slip Jigs, as they are called, according to locality, a quotation from Wilson’s Companion to the Ballroom may not be out of place. The author, who styles himself “Dancing Master from the King’s Theatre Opera House, London,” was not handicapped by any shrinking modesty which would restrain him from criticising others in his profession, says in his preface: “In the progress of this work a number of tunes have been collected together in nine-eight, as they require in their application to the figures, either in country dances or reels, what are technically termed Irish Steps. Few tunes of this measure are to be found in collections of Country Dances; and the reason is, those who are but indifferent dancers are not acquainted with proper steps.

“Some are apt to imagine that an Irish tune must be uniformly danced with Irish steps. This, however, is a mistake. It is to the tune, and not the nationality of the tune to which the steps in question are applied, and tunes in nine-eight always require Irish steps, whatever may be their origin; while Irish tunes of six-eight or common time are danced like others. This variety of Irish time has little or no recognition in modern music, and some persons appeared incredulous when arrangement in nine-eight time was mentioned.”

“The Rocky Road to Dublin,” probably the most widely known of Hop or Slip Jigs, is not one of the oldest. The earliest printed versions which we have found are in The Citizen magazine, published in Dublin, in 1841. The musical editor, Dr. Hudson, says it is a “modern Irish dance.” It is said the name is taken from a road so called in the neighborhood of Clommel. It is the air which is sung by the nurses for their children in a great portion of the southern parts of Munster, and they frequently put forward as one of their recommendations that “They can sing and dance the baby to `The Rocky Road’.” Under the above name a version of it was printed without comment in Petrie’s Complete Collection of [risk Music, and a variant also appears as “Black Rock,” a Mayo jig. As “Black Burke” it was found in a publication the name of which is forgotten. Our setting of this famous tune, obtained from John McFadden, consists of three instead of the ordinary version of two strains.

An uncommonly fine tune of this class, in three strains, obtained from John Ennis, is “Will You Come Down to Limerick?” Simpler versions are known to old-time musicians of Munster and Connacht, and in Chicago. Ennis had no monopoly of it, for it was well known to Delaney, Early, and McFadden. As an old-time Slip Jig it seems to have been called “The Munster Gimlet,” a singularly inapt title; but when it came into vogue by its song name, we are unable to say.

It would be too tedious to discuss in detail the many excellent and hitherto unpublished Hop Jigs gathered and printed through patient and persistent efforts maintained from year to year, so we will conclude the discussion of Jigs by a brief allusion to “The Kid on the Mountain.”

This unpublished tune in six strains was introduced among our experts by the “only” Patsy Touhey, the genial, obliging and unaffected wizard of the Irish pipes. A version of this tune, with the puzzling title, “Bugga Fee Hoosa,” I find is included among the numbers in Dr. Joyce’s Old Irish Folk Music and Songs.

To hear Touhey play this jig as he got it from his ancestors was “worth a day in the garden” to any one interested in the Dance Music of Ireland.

“Oft have I heard of music such as thine,

Immortal strains that made my soul rejoice,

Of wedded melody from reed and pipe, the voice,

And woke to inner harmonies divine.”