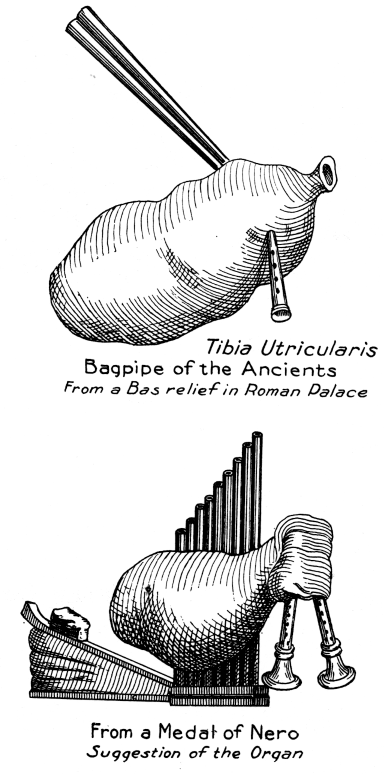

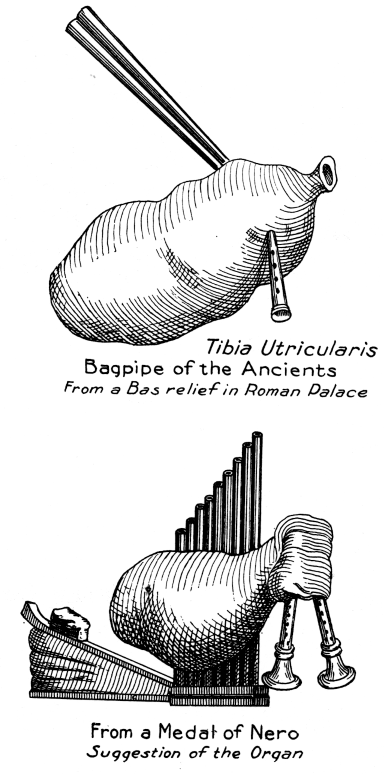

IN the minds of the English-speaking races of the present day, the bagpipe is invariably associated with scenes of Irish and Scottish life, yet the instrument in some shape or other turns up in every quarter of the globe. Omitting the various names by which it is referred to in scriptural times, we hnd that it was known in Persia as the nei aubana; in Egypt as the Zouhara; in Greece as the askaulos; and by the Romans as the tibia utricularis. In Germany they had the sacpfeiffe and dudel-sac; in ltaly the Zampogna, and the cornamusa; in France the musette and chalumeau. In Russia the bagpipe is termed volynska; in Spain, gheeyita; in Norway jockpipe; in Lapland walpipe; in Finland pilai; and in Wales pyban; dittering but little from pipai the generic name for all kinds of bagpipes in Ireland and Scotland.

Anyone desiring to learn all about the origin and pedigree of the bagpipe in all its guises and developments among all races and in all ages from savage to civilized, should lose no time in consulting Grattan Flood’s latest work, The Story of the Bagpipe.

No better proof of the antiquity of the bagpipe in Ireland need be adduced according to the author, than the reference to it in the Brehon laws of the fifth century. On this point, in his lecture on the “Music and Musical Instruments in Ancient Erinn,” O’Curry says: “Like the pipers themselves, I have not met in any ancient composition more than one reference to the Pipaireadha or pipers.

This reference is preserved in a fragment of ancient laws in the library of Trinity College. Dublin. The article contains a list of the fines or recompense, paid to professors of the mechnical arts for insults or bodily injury, and concludes in these words: `These are base, that is inferior professions, and entitled to the same amount of fines as the Pipairedha or pipers; and the Clesamhnaigh, or Jugglers: and the Cornaireadha, or trumpeters; and the Cuislennaigh or pipe blowers.' This paragraph is valuable, O’Curry adds so far as to show that the Cuislennaigh or pipe blower, was a different person from the Pipaire or piper.

The Cuisleannach or pipes were among the favorite musical instruments at the great triennial Paris at Tara which continued from pre-Christian days to the year 560 A. D., when the glories of “Tara’s Hall” came to an end.

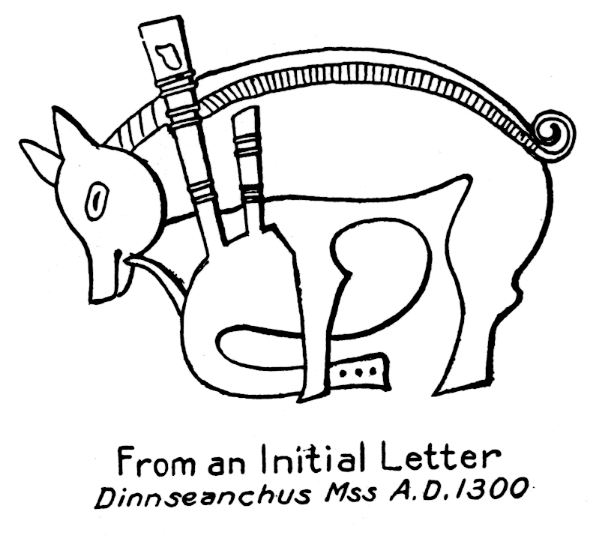

Mention is also made in Irish writings late in the tenth century of pipers and mna-caointe attending a king’s funeral. Even at religious service in early Christian times the bagpipe was utilized occasionally according to Grattan Flood, “either as a solo instrument or to sustain the sacred chant.”

Although Giraldus Cambrensis does not mention the bagpipe specifically as an instrument in use in Ireland in his time, there can be no doubt that it was known, as it is enumerated among the musical instruments at the fair of Carman, held triennially, commencing with the eighth century. The sixty-third stanza of the poem describing the fair begins thus:

“Pipes, fiddles, chainmen,

Bone-men, and tube-players.”

When Cambrensis wrote, the harp or clarseach, always the glorified instrument, had attained such popularity as to relegate the bagpipe to comparative obscurity, its use being confined to the peasantry exclusively even long after the Norman invasion. There is no evidence to show that it was used in war or as a military instrument prior to the fourteenth century. The mention of "Goetfrey

the Piper" and ~”William the Piper" in the years 1206 and 1256 respectively, among the deeds of the Priory of the Holy Trinity, Dublin; (Christ Church Cathedral,) sets at rest all doubts of the existence of the bagpipe in Ireland when Giraldus Cambrensis wrote.

It is also a matter of record that Irish pipers were among the Irish troops led by the Prior of Kilmainham, who in 1475 accompanied King Edward the Fourth to Calais.

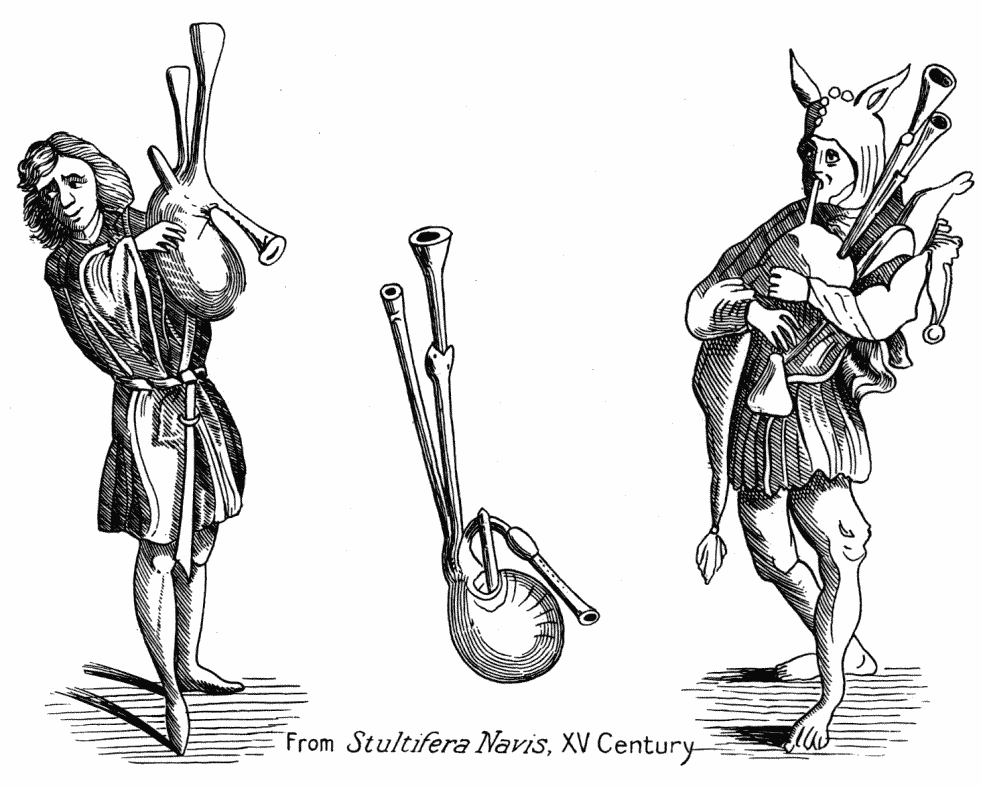

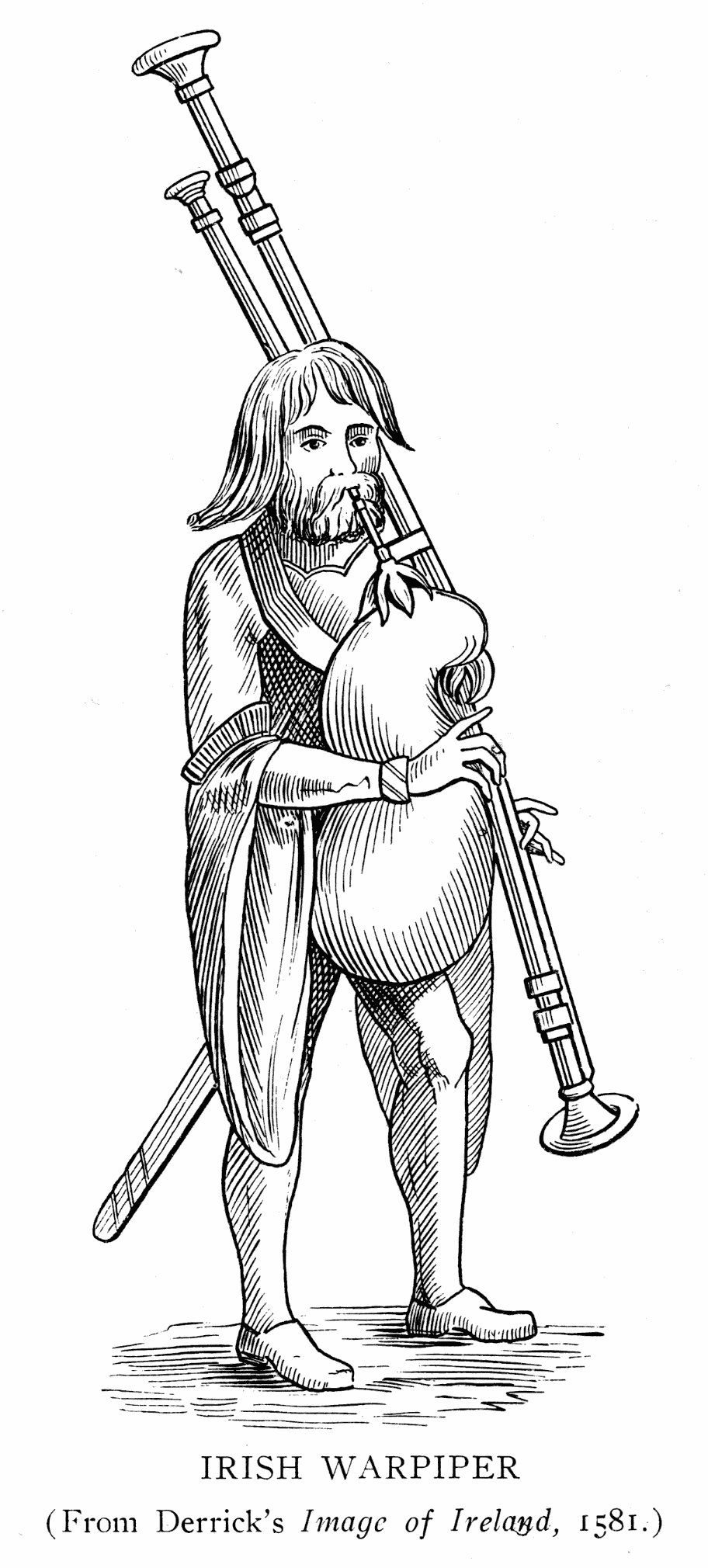

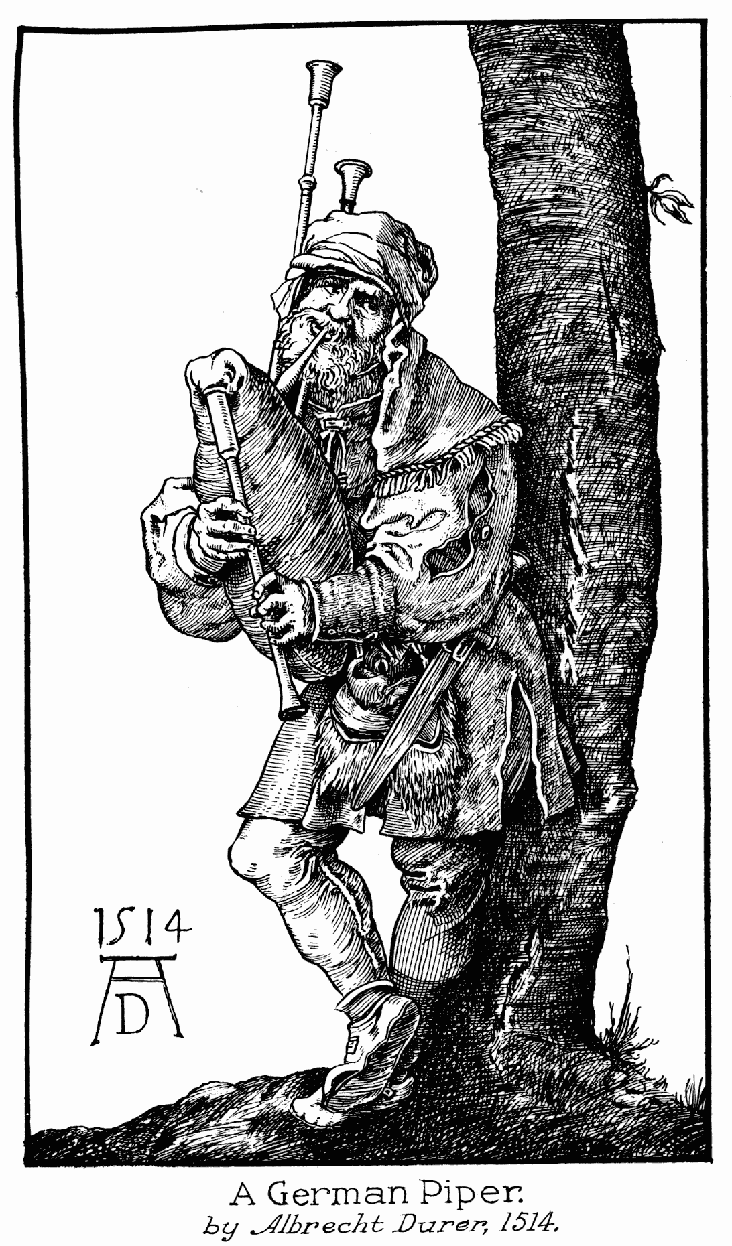

From the picture of a warpiper in Derrick’s Image of Ireland, published in 1581, even it not strictly accurate, we may obtain a fair idea of the costume and instrument of those times. A much finer type of the Irish warpiper is that credited to Albrecht Durer early in the sixteenth century. The original painting adorns a gallery in Vienna. Unlike the German piper painted in 1514 by the same artist, the Irish piper is not listed in any copy ot his works which we have seen. At any rate the picture is uninistakably that of an Irish Warpiper, for a glance will convince the most incredulous of the general resemblance it bears to that in Derrick’s work above named.

We may wonder how the great Bavarian painter came to meet such a subject for his brush, but when we come to consider that he traveled extensively in Europe, visiting Alsace and the Netherlands twice, and that Irish Kerns, accompanied of course by their pipers were engaged in the campaign at Tournay, Belgium, in 1513, and that Irish pipers accompanied the Irish troops at the siege of Boulogne in 1544, the question ceases to be a matter of speculation.

All throughout the centuries when warpipes were used by the Irish as a part ot their military equipment. Little Irish history was made in their absence, though their participation in the activities of warfare was not specifically mentioned. In forays and battles the pipers took literally a foremost part. Being always in the lead, and heroically remaining to encourage their troops with spirited war tunes, until death or defeat silenced their strains.

The Irish advanced to the charge at the famous battle of Bel-an-atha-buidhe, or the Yellow Ford, in 1598 to the stirring strains of the warpipes, and many instances are cited by Grattan Flood where the warpipes were used effectively. In the language of Standish O’Grady: “They were brave men those pipers. The modern military band retires as its regiment goes into action. But the piper went on -before his men and piped them into the thick of the battle. He advanced sounding his battle pibroch, and stood in the ranks of war, while men fell all around him.”

It was the patriotism and loyalty of the pipers, more than anything else that led to the enactment of the Statutes of Kilkenny in 1367. In the reign of Edward the Third, pipers or minstrels, storytellers, bablers, rimers, etc., were attainted and imprisoned as well as those of the English in Ireland “who receive or give them anything.” One piper, Dowenald (probably Dhonal) O’Moghane, was exempted from the operations of this law by special enactment because “he had constantly remained in the fealty, peace and obedience of the king; and that he had inflicted divers injuries on the Irish enemies for which he durst not approach near them.”

This harsh law was the first severe blow struck at the popularity of the bagpipe, although in course of time the rigors of its enforcement subsided, and those against whom the law Was directed, went among the English and exercised their arts and minstrelsies, and returned to the "Irish enemies” with whatever information they secured.

While we may not be particularly concerned in the identity of the warpipers who accompanied the Irish Kerns in their campaigns in Scotland, and on the continent, in the fifth decade of the sixteenth century to bolster up the interests of English royalty, we cannot help voicing our regret that history has not preserved the names of the pipers who rendered such valiant service at the battle of Bel-an-atha-buidhe (Yellow Ford) in 1598, and at the battle of Curlew Mountain one year later, and above all at the battle of Fontenoy in 1745.

For the description of the bagpipe, or warpipe as it existed in the sixteenth century, we are indebted to Richard Stanyhurst, who, writing about the year 1584, says: “The Irish likewise, instead of the trumpet, make use of a wooden pipe of the most ingenious structure to which is joined a leather bag, very closely bound with bands. A pipe is inserted in the side of this skin, through which the piper, with his swollen neck and puffed-up eheeks, blows in the same manner as we do through a tube. The skin, being thus filled with air, begins to swell, and the player presses against it with his arm; thus a loud and shrill sound is produced through two wooden pipes of different lengths. In addition to these, there is yet a fourth pipe, perforated in different places, which the player so regulates, by the dexterity of his fingers in the shutting and opening the holes, that he can cause the upper pipes to send forth either a loud or a low sound, at pleasure. The principal thing to be taken care of is, that the air be not allowed to escape through any other part of the bag than that in which the pipes are inserted. For if anyone were to make a puncture in the bag, even with the point of a needle, the instrument would be spoiled, and the bag would immediately collapse, and this is frequently done by humorous people when they wish to irritate the pipers.

“It is evident that this instrument must be a very good incentive to their courage at the time of battle, for by its tones the Irish are stirred up to fight in the same manner as the soldiers of other nations by the trumpet.”

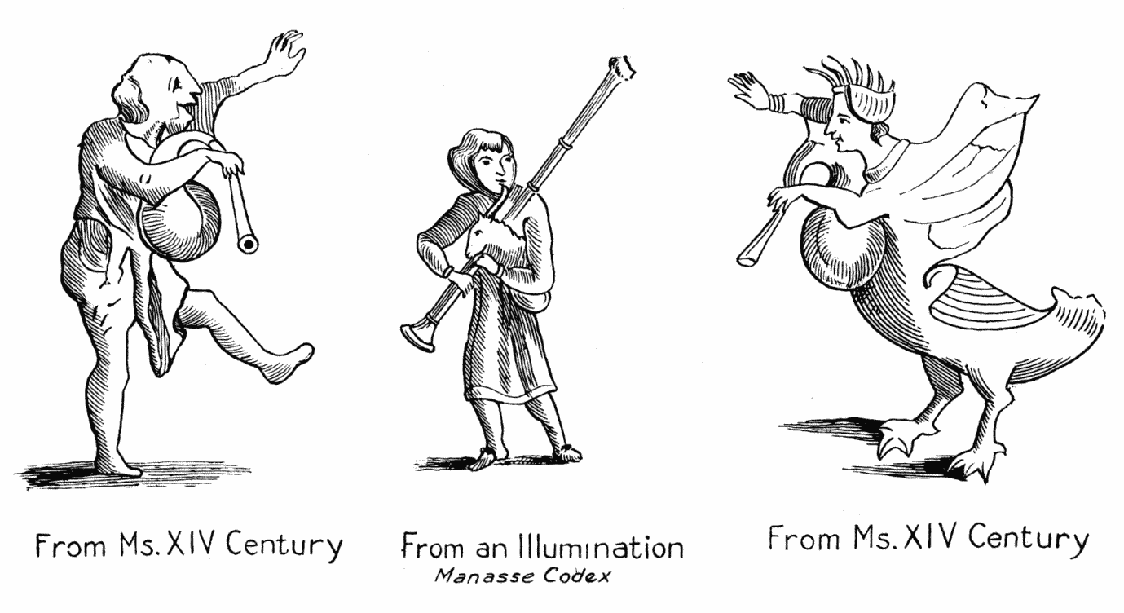

Illustrations of the Piob Mor or warpipes of this period described by Stanyhurst, from the brush of different artists, prove conclusively that the instrument was both ornate and imposing, and it would appear superior in workmanship to the warpipes of today.

Some writers assume that the terms “Cuisle pipes” and “Uilleann pipes” are synonymous or interchangeable. On this point there appears to be a hook on which to hang an argument. That there were two methods of holding the bag admits of no question. In the more ancient pictures of pipers, it will be noticed that the instrument is suspended by a strap or band passed over the shoulders.

While the bag rests on the perforiner’s breast and stomach as in Albreeht Durer’s paintings of a German piper, and an Irish piper at the beginning of the sixteenth century. The picture of the Irish warpiper in Derrick's Image of Ireland, published in 1581, displays a similar arrangement. This style would naturally be called the “Cuisle pipes,” as the pressure on the bag to expel the air is exerted by the forearms or wrists-hence, cuisle, or pulse.

A later development of the warpipe was in placing the bag, much diminished in size, under the arm, in which position the necessary pressure is administered by the elbow or Uilleann.

The war pipe may be of either design when blown from the mouth, but it will be noticed that Uilleann as a descriptive term for the bagpipe did not come into use before the last quarter of the sixteenth century - 1584, Grattan Flood says, and that was about the time when the change just mentioned took place. However, the Uilleann pipes of those days were still the warpipes or Piob Mor; and they must not be confounded with the Uilleann or Union pipes which were practically a new instrument, developed in the early years of the eighteenth century.

Shakespeare’s “woollen bagpipe,” so frequently alluded to, and of late plausibly explained as meaning Uilleann bagpipe, affords no cause for speculation in the edition of his works in the writer’s library, published in 1803, for the expression is plainly printed “swollen bagpipe”; a designation singularly appropriate.

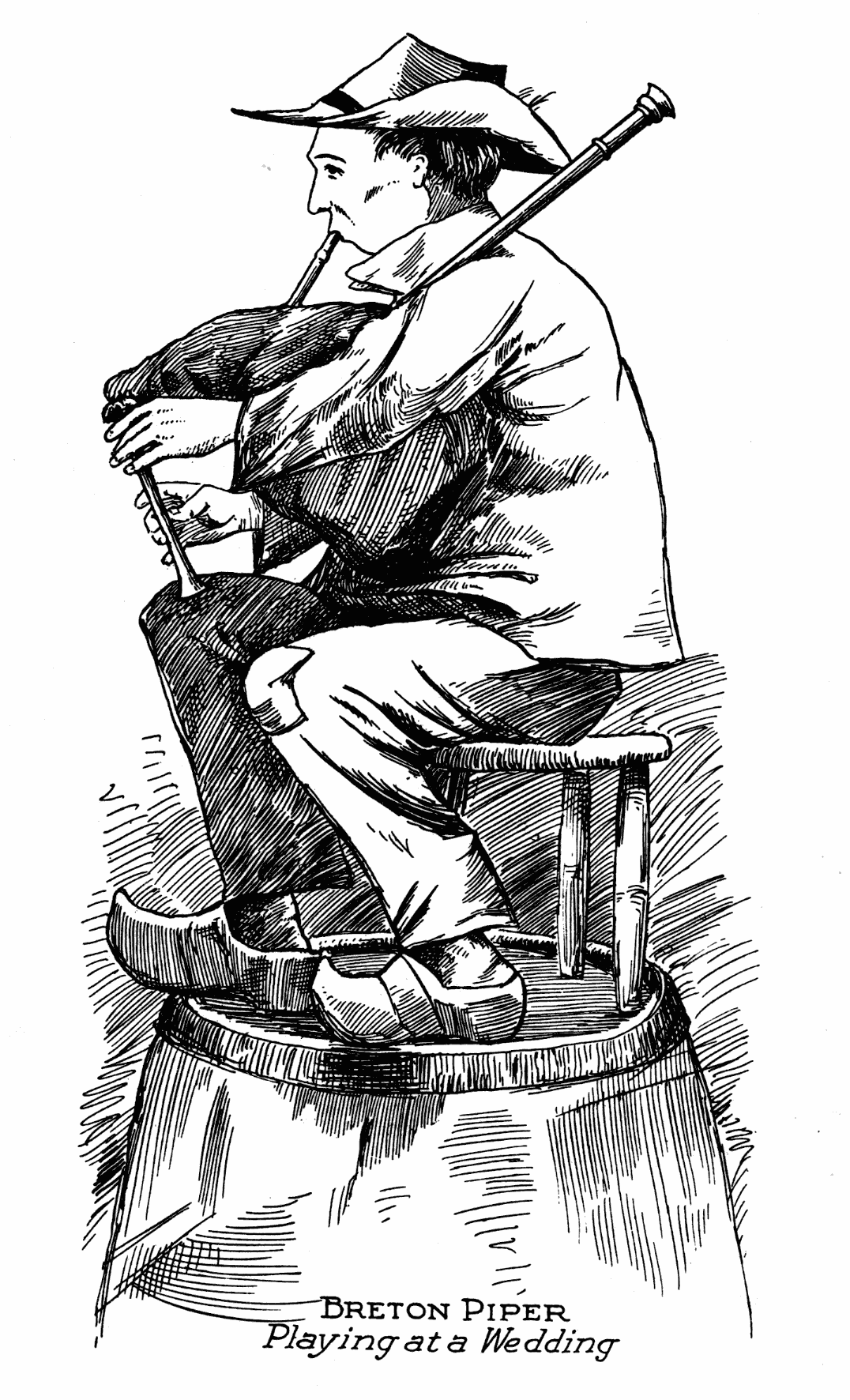

After the Uilleann pipes had been modified in tone, and blown with a bellows, and had the drones arranged compactly and horizontally in a stock, the instrument was more in demand at social gatherings, and such festivities as weddings and ehristenings; but this type, on which the piper played while seated, did not by any means supplant the Piob Mor at funerals, football and hurling matches. Only a generation or so ago, Mr. Wm. Halpin of Newmarket- on-Fergus headed the Clare hurlers on their way to compete with their Limerick rivals, playing on a set of Highland pipes, which was in fact the Piob Mor of both Scotland and Ireland for many a day, though a third drone had been added.

As Grattan Flood says, “from grave to gay, the bagpipe was requisitioned, and no important Irish funeral took place unless headed by a band of war pipers.” At the burial of a remarkable dwarf piper named Mathew Hardy, in 1737, the funeral cortege was led by “eight couple of pipers, playing a funeral dirge composed by O'Carolan. Gradually the warpipes were superseded by the Union pipes for domestic use, and by trumpets and drums for military purposes. The last occasion of which there is any historical mention of Irish pipers in war was at the battle of Fontenoy, May 11, I745, when the Irish Brigade in the service of France turned the tide of battle against the English troops. Very appropriately, two of the tunes those intrepid expatriated pipers pealed out were “The White Cockade” and “Saint Patrick’s Day in the Morning.”

In Dissertations on the History of Ireland, published in 1766, the learned Charles O’Conor of Belanagar says: “The instrumental music in the chase, as in the field of battle, was sounded by wind instruments, what they called Adhar-caidh Cuiul.” This term is literally musical horns, and not a musical bag, as translated by Walker and others. What words could more aptly describe a set of bagpipes of the old type than musical horns?

In his correspondence with Dr. Walker at a much later date, O’Conor mentions the Cuisle Cuiul as “a simple kind of bagpipe, loud-toned and confined to a bare octave.” This nurnber of notes agrees exactly with the primitive bagpipe pictured in Dr. Ledwich’s Antiquities of Ireland, which has but six vents for the fingers and one for the thumb. An additional vent for the little finger of the right hand, of later introduction, increased the capacity or compass of the so-called warpipe chanter.

When the Piob Mor or Warpipe was transformed into the Irish or Union pipes, is largely a matter of conjecture, as the old form continued in use long after the transformation was made. The first performer on the improved instrument of whom we have any historical record was Lawrence Grogan of Johnstown Castle, Wexford. Grattan Flood credits him with the authorship of both words and music of “Ally Croker,” in the year 1725. We must, therefore, place the origin of the Irish pipes some few years before that date.

As the harp declined, the new type of bagpipe, improved from time to time, gained immensely in popularity. The extent to which it had been developed from a loud-toned instrument of but one note more than an octave in compass, to two full octaves, may be realized from Dr. Burney’s description in 1775: “The instrument at present in use in Ireland,” he says, “is an improved bagpipe, on which I have heard some of the natives play very well in two parts without the drone, which I believe is never attempted in Scotland. The tone of the lower notes resembles that of a hautbois and clarionet, and the high notes that of a German flute, and the whole scale of one I heard lately was very well in tune, which has never been the case of any Scots bagpipe that I ever heard.” The Irish bagpipe in its improved form had not been deemed unworthy of the ear of royalty, at least a score of years before the date of Dr. Burney's description, for a footnote in Walker’s Historical Memoirs of the Irish Bards informs us “that George the Second was so much delighted with the performance of an Irish gentleman on the bagpipes that he ordered a medal to be struck for him.”

Modern writers assure us with confidene that the qualifying word Union, as applied to the improved Irish bagpipe, is simply a corruption of the Irish term Uilleann, in use for over two hundred years. Quite as plausibly might we advance the claim that the word Union is aptly descriptive of the modern Irish instrument, which is in fact a union of two instruments - namely, the simple bagpipe and the organ. Since the adoption of the regulators which produce the organ tones, the Irish or Union pipes have been frequently alluded to as the Irish organ.

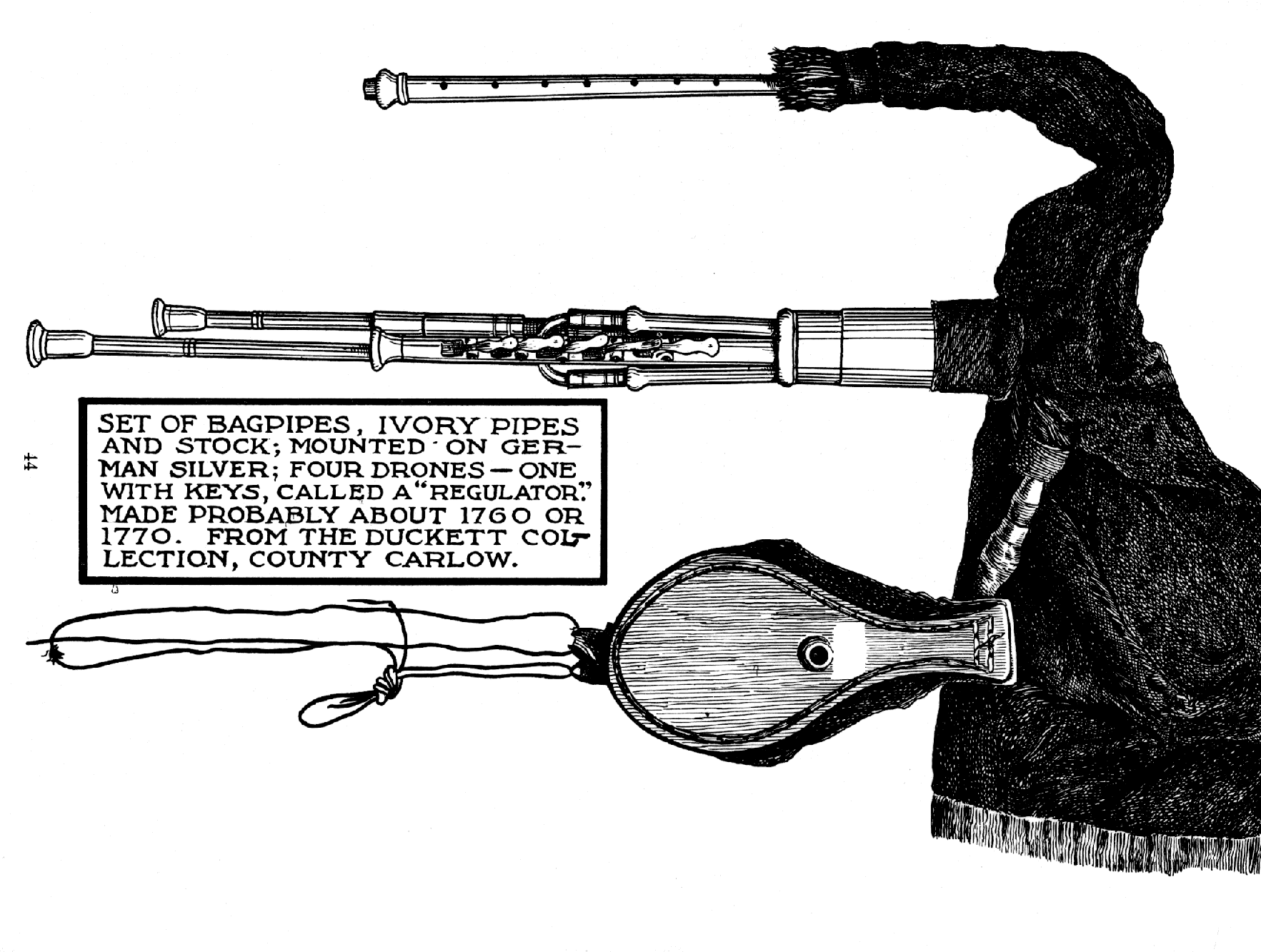

It will be noticed that Dr. Burney, above quoted, makes no mention of keys or regnlators on the “improved bagpipe” of his day, nor are there any on the fine old specimens of an Irish bagpipe pictured on page 40 of Duncan Fraser’s work on The Bagpipe, although it has four drones closely set in the stock. Elaborate instruments or “sets,” equipped with keyed chanter and regulators, were turned out between 1770 and 1790, by the elder Kenna, a renowned pipemaker of Dublin, and it was about that time, or perhaps later, that the Irish bagpipe became known as the “Union Pipes.” As a specimen of a still earlier development of the Union bagpipe, the picture of the Carlow instrument presents an interesting study.

This name, as far as the present writer is aware, was first seen in print in O'Farrell's Collection of National Irish Music for the Union Pipes, published about the end of the eighteenth century. The following extract from the author’s introduction would seem to justify the name: “The Union Pipes-Being an instrument now so much improved as renders it able to play any kind of Music, and with the additional accompanyments which belong to it, produce a variety of pleasing Harmony which forms as it were a little Band in itself.’,

Not a few combining both musical and mechanical genius contributed to the further development of the Union pipes, down to late in the nineteenth century. The number of regulators were increased to three in standard instruments; then a fourth, and even a fifth, was ultimately added, until, as Manson the Scotch authority says, the Irish pipes have been elaborated to such a degree that they have almost ceased to be bagpipes.

The soft, plaintive tones of the pipes manufactured by Kenna, Coyne, and Egan, so delightful in the parlor, proved too weak to produce the desired effect in concert halls and/theatres of modern times, so William Taylor, a Drogheda pipemaker, who came to New York City in 1872, and settled in Philadelphia about 1874, developed an instrument of powerful tone and concert pitch, which met all requirements in that respect.

As the limit of development had been reached, the vogue of the bagpipe had declined, and notwithstanding the agitation for its revival in recent years, the outlook to an enthusiast presents but little ground for optimism.

It is unfortunate that the teaching of Irish pipe music has not been standardized, as that on the Highland pipe has been. The system of execution on the latter instrument is uniform; and as all Highland pipers learn from written music, under competent instructors, whether in Scotland, England, Canada, or the United States, they are `enabled by the uniformity of their system to play together, in perfect accord, upon all occasions.

That a School of Piob Mor or warpipe music existed in Ireland as late as the middle of the seventeenth century, is beyond question, for we find that Domhnall Mor, or Big Donald MacCrimmon, son of John, the founder of the famous College of Pipers, in the lsle of Skye, was sent by his chieftain, MacLeod, to a school or college of pipers in Ireland, to perfect himself on the instrument.

From this it would appear that before government persecution chilled their ardor, te Irish pipers were as renowned in their line as were the harpers.

What might he written on this subject would not alone fill a volurne, hut several of them, for in recent years three separate volumes have been written on the bagpipe - two by Scotch authors, Duncan Fraser and W. L. Manson, and one by our own Grattan Flood, Mus. Doc. Even so, they did not by any means exhaust the subject. In Manson’s work, a whole chapter is devoted to the shafts of ridicule and uncomplimentary criticism aimed at the Highland bagpipe and its music, all of which might have been said as deservedly of the Irish warpipes, espeeially if out of tune, and in the hands of an incapable performer. Yet, strange to say, although the English pipers were also favorite targets for the scoffers in their day, nothing except that which is commendable has come down to us concerning the lrish pipers or their performance.

It is now generally admitted that the Scotch got their musical instruments, as they got their music and language, from Ireland. Since the colonization of Scotland from Dalaradia in Ulster, about the year 504, regular intercourse between the two countries has ever since been kept up.

However long the bagpipe may have been in use in Scotland, historical mention of it had been wanting until early in the fourteenth century. The precise date of the bagpipes introduction to Scotland is unknown a writer in an Edinburgh publication of 1911 says: “Certainly it was in evidence during the twelfth century, and authentic records show that pipers formed a part of the king’s retinue during the fourteenth.” From all we can learn there was no essential difference between the Seoteh and lrish warpipe until early in the eighteenth century, when the third or bass drone was added to the Scotch instrument. About the same time the Irish warpipe was transformed into the Union pipes already described.

To discuss the origin of the bagpipe in Scotland, or Ireland, would lead to nothing definite, as the diversity of views expressed by writers on that subject is simply bewildering. The opinion that it was derived from the Romans has been discarded by such modern authorities as Manson, Duncan Fraser, and Grattan Flood.

The bagpipe belonged to the Celts, and its existence can be traced to their colonies all the way from ancient Scythia via the Black Sea, and the Mediterranean to the shores of Britain. In the absence of evidence, much is left to conjecture, yet the claim is now confidently made that the bagpipe arrived with the Celts long before the Roman invasion. “Tell me where the old Celt settled,” says Duncan Fraser, “and I will tell you where to look for the bagpipe.” `

After disclaiming any obligation to the Scandinavians, Romans, English, or continental nations for the introduction of the bagpipe into Scotland, W. L. Manson says: “Ireland indeed can put forward a good claim - Christianity came from there, the peoples are the same, and the relations between the two countries in early days were very c1ose - but there is less to uphold the claim than there is to show that the pipes are native to the Highlands.” In their migration from the borders of the Black Sea, along the Mediterranean shores, and thence northward by way of the Iberian peninsula, the Celts would be certain to colonize Ireland long in advance of their advent in Caledonia. Besides, we must not forget that Ireland was better known to the ancients than Britain. There can be no question, however, that the bagpipe in form, development, and use, was essentially the same in both countries down to the beginning of the eighteenth century when radical changes took place.

As an instrument of war and peace with tones clear, powerful and penetrating, it voiced the national melodies. It had been associated with all the activities of Gaelic life from the cradle to the grave. No single musical instrument ever devised by man united in itself so wide a range of utility as the Piob Mor of the Gael. In the language of Lieut. MacLennan of Edinburgh, it pealed forth merry melodies in the halls of the chieftains at the birth, and baptism of the heir. At marriages convivial parties, festive gatherings, dances, and other amusements, it was indispensible. It accompanied the workman to lighten his labor. Its steady measured notes assisted and solaced the soldiers in their long and painful marches, through rocks, rivers, and deserts. It summoned the clansmen when danger was near, and it stimulated and inspired the Highlander with courage and determination on the field of battle. It had from remote times its share in solemn acts of devotion in the sanctuary, and at funerals the melancholy wailing of the lament played on the bagpipes, could give expression to the grief of the relatives better than any other instrument.

Coming frorn the pen of W. L. Manson, a Scotch writer, the subjoined quotation from The Highland Bagpipe cannot fail to be of interest to the general reader particularly as his views cannot have been the result of either partiality or prejudice.

“Passing from debatable ground, the result of our assortment of quotations, seems to be that the tirst thoroughly authentic reference to the bagpipe in Scotland, dates from 1406, that it was well known in Reformation times, that the second drone was added about 1500, that it was first mentioned in connection with the Gaelic in 1506 or a few years later, that it was classed in a list of Scottish musical instruments in 1548, that in 1549 and often afterwards it was used in war, that in 1650 every town had a piper, that in 1700 the big drone was added, and that in 1824 the Scots were enthusiastic about the pipes.

There is not the slightest doubt of course, that the instrument was used in Scotland for many years, probably for centuries before we can trace it, but previous to the dates given we have only tradition and conjecture to go by.” The Highlander in his time of greatest adversity, the same author says, stuck to the pipes so the pipes seem determined to stick to the Highlander in spite of the tendencies of latter day civilization.

The transition from the harp to the bagpipe was spread over two centuries. In the middle of the sixteenth century both instruments were in use, but in the seventeenth century, there were few harpers while the civil wars gave bagpipe music an impetus, on account of its superiority in the noise and tumult of battle as a military instrument. Besides supplanting the harp - Manson continues - the pipes also supplanted the bards themselves. The clan piper was second in importance to the chief.

The Scottish bards hated the growing popularity of the pipes, as ardently as the Irish pipers despised the introduction of brass bands, but the world moves, and the keenest satire of the former and the bitterest invective of the latter, were alike powerless to retard or stay the progress of either rival.

The last clan bard, Neil Mac Mhuirich, died in 1726, and the last clan harper in 1739, when the hereditary pipers were in all their glory, living from generation to generation in the family of the chieftain at the head of their respective clans. Not only were the clan pipers of superior rank to other retainers of their chief but they were provided a servant or gille to carry their pipes. And though the pipers of our day have fallen from their high estate so have many of their historic patrons. Today the McLeod of Dunvegan, is a poor man. In a year of famine to keep the crofters from starving he emptied his own purse.

The use of the Piob Mor, or Highland pipe in connection with Highland regiments, has well served to maintain its popularity as the national instrument, there being at the beginning of the twentieth century twenty-two pipe bands in the British army. It is said that from the year 1750 to 1800, the Isle of Skye in the Hebrides alone furnished 500 pipers for military service.

A curious circumstance is the favor shown this class of music by ancient races. “The only foreign music the Chinese masses have shown any interest in is the skirling of the bagpipes of the Cameron Highlanders”, the American Consul General at Tientsin tells us, and although wealthy Chinese occasionally purchase pianos they use them simply as pieces of furniture.

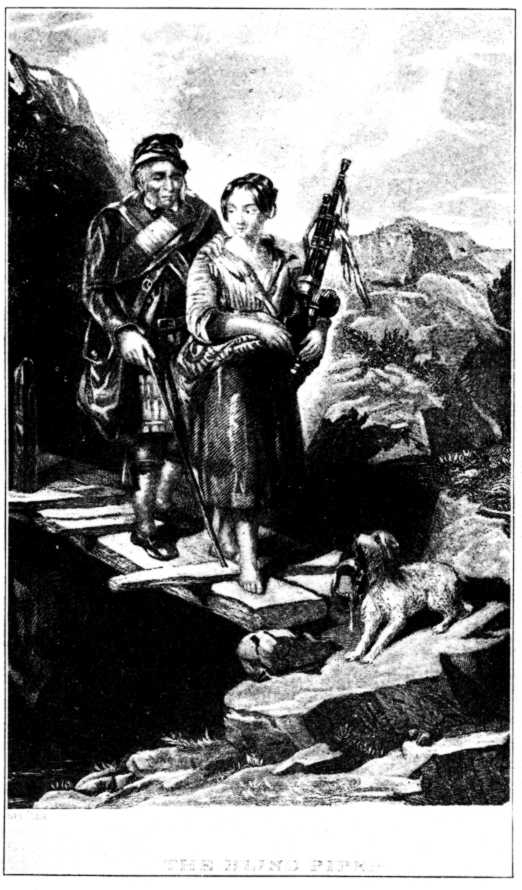

Differing in the arrangement of the drones from all other representations of the Scottish bagpipe with which we are familiar, is that drawn by Sir David Wilkie R. A. In “The Bagpiper,” one of his earliest paintings; and “The Blind Piper,” from the brush of J. Naysmith, another famous Scotch artist, of about a century ago.

It is worthy of note that the so-called Brian Boru Warpipes lately manufactured in London are modeled after those peculiar instruments.

It has been generally conceded that the Romans introduced the bagpipe into Britain about the middle of the first century. It was the military instrument of the Roman infantry, while the trumpet was assigned to the cavalry. Yet if the Celtic inhabitants of Hibernia and Caledonia were in possession of the bagpipe before the Roman invasion as now claimed by such authorities as Manson, Duncan Fraser, and Grattan Flood, there can be no reason to doubt that it was known to the ancient Britons also.

That it was the pastoral instrument of Britain in the ninth century is evident, for we fnd the shepherd in Evans' Old Ballads whom King Alfred visits in disguise declares that his

“Bagpipes shall

Sound sweetly once a year,

In praise of his renowned king.’,

Although the earliest mention of the bagpipe in English literature is to be found in the prologue to Chancer’s Canterbury Tales, evidence is not wanting to show that it was by no means rare at least a eentnry before his time. Illustrations, cathedral windows, and payments to pipers, attest the bagpipe’s popularity in the fourteenth century. Its crowning glory, however, was the inclusion of pipes in the royal bands. Queen Elizabeth's “Band of Musick” in 1588 consisted of 16 trunipets, 9 minstrels, 8 viols, 6 sackbuts, lutes, harps, 3 players on the virginals, 2 rebecs, and 1 bagpipe.

The bagpipe also enjoyed the favor of Kings Edward the Second, and Edward the Third, who retained performers on the instrument in their musical establishments. King Henry the Eighth of unsavory memory, who had musical as well as more reprehensible tastes, left in his collection four such instruments “with pipes of ivorie.”

The English bagpipe until the year 1300, or so, consisted of but the bag, blowpipe and chanter. The first instrument pictured with a drone is to be found in the Gorleston Psalter, written about 1306. the second drone being added a century later. Thus improved it is frequently referred to as the “Drone” or “Dronepipe.”

In the pages of Knights’ Old England describing the customs and habits of the outlaws of Sherwood forest in the days of Robin Hood, we read “of enjoyment in their shooting and wrestling matches, in their sword fights, and sword dances, in their visits to all the rustic wakes and feasts of the neighborhood. How the outlaws would be visited by the wandering minstrels coming thither to amuse them with old ballads, and to gather a rich harvest of materials for new ones. The legitimate poet-minstrel would be followed by the humbler gleeman forming one of a band of revelers, in which would be comprised a taborer, a bagpiper and dancers and tumblers.”

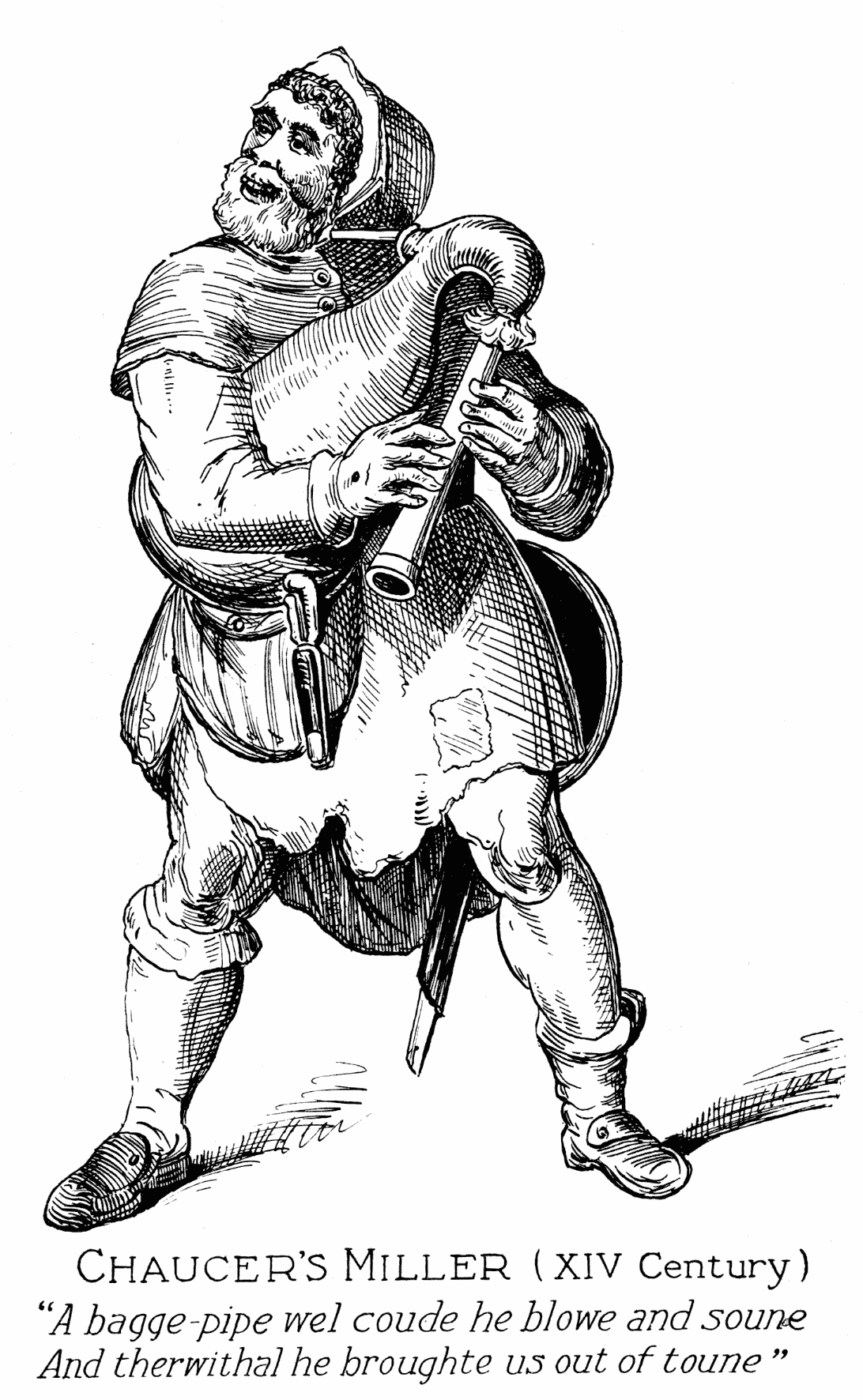

The above refers to times a generation or so before Chaucer introduces his miller Who led the procession from Southwark to Canterbury and the shrine of Thomas a Becket.

“A bagge-pype wel coude he blow and soune

And therwithal he broughte us out of toune."

The author tells us that a bagpiper marched or rode in front of the bands of pilgrims on their way to some favorite shrine - a frequent sight in those days - cheering on the weary-footed with his gay music.

It will be observed that the bagpipe which innnortalized Chaucer’s miller as well as others of the fourteenth century, had no drone; neither had the instrument played by the piper accoinpanied by the drummer which illustrates the scenes of the early part of the seventeenth century in Chapter 3, Vol. 2 of Knights' Old England.

In mediaeval England the bagpipe was used In connection with church services, as it was used in Ireland. And Scotland, cspecially in processions and outdoor religious ceremonies, but it was at games and May Day dances that the bagpipe was given preference over other instruments.

“I have seen the Lady of the May,

Set in an arbour on a holy day,

Built by the May-pole where the jocund swains

Dance with the maidens to the bagpipe's strains.”

Illustrating this quatrain from Browne's Pastorals, written in 1625, the piper is seated on a tall barrel or puncheon near the Maypole, while the dance goes gaily on all around him. In this picture the bagpipe is equipped with two drones. and so is the instrument played on bv the piper in Hogarth's "South-wark Fair”.

Though enjoying the favor of royalty during several reigns. it does not appear that the bagpipe was ever used in war in England. Pipers flourished in goodly numbers early in the seventeenth century, and were as conspicuous at fairs and outdoor entertainments as their brethren in more recent times in Ireland.

At no stage of its development was the English instrument at all comparable

in style or finish with the Piob Mor or warpipc of Ireland or Scotland.

The English bagpipe survived with varying degrees of popularity until early

in the eighteenth century, although the Northumbrian pipes - a distinct and much

improved variety-remainetl in favor for a generation or two afterwards;

and from recent accounts it is not yet altogether extinct.

We can safely assume that the bagpipe was known to the Cambrians long anterior to its mention in authentic history, for we are assured by no less an authority than Prof. Kuno Meyer, the renowned philologist, that the Gaels of Ireland made various settlements in Wa1es in the third and fourth centuries, and the intercourse between the two countries was always of a friendly character and long continued.

Being in great favor with Grutfydth ap Conan King of North Wales, it was given much prominence at an Eisteddfod or Feis held in the year 1100, on which occasion Grattan Flood tells us an Irishinan was the prize-winner.

Much earlier reference to the bagpipe, perhaps in a simpler form, is that found in the institutions of the Welsh King, Howel Dha, (Howel the Good), about the year 942: “Every chief bard to whom the prince shall grant an office, the prince shall provide him an instrument: a harp to one, a crwth to another, and pipes to a third; and when they die, the instrument ought to revert to the prince.”

Brompton, an English historian enumerates the bagpipes among the Welsh musical instruments in 1170, and Giraldus Cambrensis corroborates him in 1185. The popularity of the harp overshadowed it to such an extent in the next century that the bagpipe may be said to have disappeared in Wales at the opening years of the fourteenth century.