FAMOUS HARPERS IN THE SEVENTEENTH AND LATER CENTURIES

The rolls of fame I will not now explore,

Nor need I here describe in learned lay

How forth the minstrel fared in days of yore,

Right glad of heart, though homely in array,

His waving beard and locks all hoary grey;

While from his decent shoulder decent hung

His Harp, the sole companion of his way;

Which to the whistling wind responsive rung,

And ever, as he went, some merry lay he sung.

-Beattie.

The old Irish harp has now perhaps no existence unless in the repositories of the curious. It has passed away among many other interesting relics of earlier times, which had yet a lingering existence at the close of the eighteenth century. How much more true to day than when penned by a writer in The Dublin Penny Journal eighty years ago.

Prior to the beginning of the nineteenth century, when a much simpler state of socioty prevailed, the harper was an honored guest whose appearance never failed to produce much animated excitement wherever he camo laden with the music, the provincial intelligence, and the family gossip, amassed during half a year or more tunefuk peregrination. Well may we exclaim in the words of Samuel Lover:

“Oh give me one strain

Of that wild harp again,

In melody proudly its own,

Sweet harp of the days that are gone!

Timos wide-wasting wing

Its cold shadow may fling

Where the light of the soul hath no part;

The sceptre and sword

Both decay with their lord,

But the throne of the bard is the heart!”

Manson in his great work, The Highland Bagpipe, says: In Scotland the use of the harp ceased with the pomp of the feudal system, while in Ireland the people retained for many generations an acknowledged superiority as harpers.

As this feature of the subject is dealt with in a separate chapter there is no necessity for digressing from our purpose, which is the consideration of the famous harpers who nourished subsequent to the reign of Queen Elizabeth.

MR. CLARK

Through an entry in his diary of 1653-4, John Jocelyn, an Englishman, has immortalized Mr. Clark, a gentleman of quality and parts who was brought up to the practice of the harp since his fifth year. “Come to see my old acquaintance, and the most incomparable player on the Irish harp, Mr. Clark after his travels. He was an excellent musician and a discreet gentleman. Such music before or since, did I never hear, that instrument being neglected for its extraordinary difficulty, but in my judgment far superior to the lute itself, or whatever speaks with strings.”

Though born in England, Clark following the customs of his professional brethren in Ireland, visited his patrons periodically all over the country. The date of his birth may be ascribed to the first decade of the seventeenth century.

WILLIAM FITZ ROBERT FITZ EDMOND BARRY

Strange as it may appear the above named, a blind harper, according to the records, was in the service of Lord Barrymore, who had been commissioned by Queen Elizabeth to exterminate the harpers. But this was a dozen years after her death.

MYLES O’REILLY

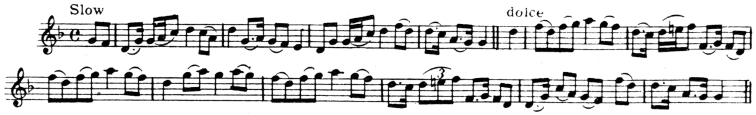

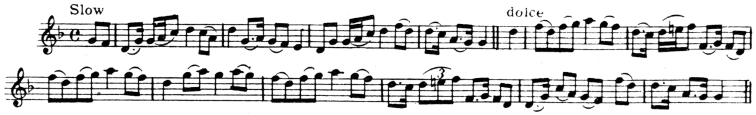

This eminent harper, as Bunting terms him, was born about 1636, and hailed from Killincarra, County Cavan. He was universally referred to by the harpers assembled at Belfast in 1792 as the composer of the original “Lochaber”, an air so called from the circumstance that Allan Ramsay wrote a song to it entitled, “Farewell to Lochaber, Farewell to My Jean.” The original air referred to as “The Irish Tune,” was printed in Thomas Duffet's New Poems, Songs, Prologues, and Epilogues, etc. published in 1676, a copy of which may be seen in the British Museum. Allan Ramsay's song appeared in the Tea Table Miscellany. Fuller information concerning this air may be found in Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby.

SIR EDWARD SUTTON

Having such a wealth of famous harpers of our own, it is not with any sinister design the above named gentleman-harper is introduced in those pages. Evelyn the English diarist, writing of him in 1668, says: “I heard Sir Edward Sutton play excellently on the Irish harp, but not approaching my worthy friend, Mr Clark, who makes it execute lute, viol, and all the harmony an instrument is capable of.”

THADY KEENAN

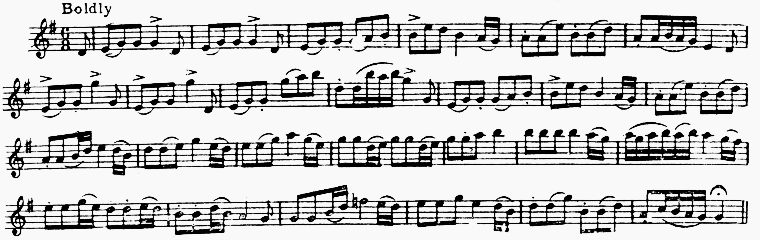

This harper, who flourished early in the seventeenth century, won immortality by his composition of that delightful air, “An Tighearna Mhaigheo,” (Lord Mayo).

The circumstances which led to its inspiration were as follows: David Murphy undoubtedly a man of genius, who had been taken under the protection of Lord Mayo through benevolent motives, incurred his patron’s displeasure by some misconduct. Anxious to propitiate his Lordship, Murphy consulted a friend, Capt. Finn, of Boyle, Roscommon. The latter suggested that an ode expressive of his patron’s praise, and his own penitence, would be the most likely to bring about the desired reconciliation. The result was in the words of the learned Charles O’Conor, “the birth of one of the finest productions for sentiment and harmony, that ever did honor to any country.” Apprehensive that the most humble advances would not soften his Lordship’s resentment. Murphy concealed himself after nightfall in Lord Mayo’s hall on Christmas Eve, and at an auspicious moment poured forth his very soul in words and music, conjuring him by the birth of the Prince of Peace, to grant him forgiveness in a strain of the finest and most natural pathos that ever distilled from the pen of man. Two stanzas will show the character of his alternating sentiments.

“Mayo whose valor sweeps the field

And swells the trump of Fame;

May Heaven's high power thy champion shield,

And deathless be his name.

“O! bid the exiled Bard return,

Too long from safety fled;

No more in absence let him mourn

Till earth shall hide his head.”

LORD MAYO

RORY DALL O'CAHAN

It is doubtful if any harper of any age was so renowned as Rory Dall O’Cahan if we except the glorified Turlogh O'Carolan. The O'Cahans were a powerful clan in the portions of Antrim and Derry called the O'Cahan country, and were loyal lieges of Hugh O'Nei11, whose harper, Rory Dall. was said to be.

Ruaidri, or Rory, born in 1646, was nicknamed Dall or blind, after losing his eyesight, it being a term commonly applied to those similarly afflicted. He early devoted himself to the harp not as may be surmised, with a view to following music as a profession for the tradition invariably preserved of him in the North is that he traveled into Scotland attended by the retinue of a gentle man of large property, and when in Scotland, according to the accounts preserved there also, he seemed to have traveled in the company of noble persons.

GIVE ME YOUR HAND

Proud and spirited, he resented anything in the nature of trespass on his dignity. Among his visits to the houses of Scottish nobility, he is said to have called at Eglinton Castle, Ayrshire. Knowing he was a harper, but being unaware of his rank, Lady Eglinton commanded him to play a tune. Taking oftence at her peremptory manner, O'Cahan refused and left the castle. When she found out who her guest was her ladyship sought and effected a speedy reconciliation. This incident furnished a theme for one of the harper’s best compositions. “Tabhair Dam Do Lamh,” or “Give Me Your Hand!” The name has been latinized into “Da Mihi Manum.”

The fame of the composition and the occasion which gave birth to it reaching the ear of King James the Sixth, induced him to send for the composer. O’Cahan accordingly attended at the Scottish court, and created a sensation.

His performance so delighted the royal circle that King James familiarly laid his royal hand on the harper’s shoulder. When asked by one of the courtiers if he realized the honor thus conferred on him, to their consternation Rory replied: “A greater than King James has laid his hand on my shoulder.” Who was that man? cried the King. “O’Neill, Sire,” proudly answered Rory standing up.

Four of the nine tunes to be found at the end of Bruce Armstrong's fine work on The Highland Harp, are attributed to “Rorie Dall”, namely “Lude's Supper;” “The Terror of Death;” “The Fiddler's Content ;” and “Rorie Dall’s Sister’s Lament.” Others of his compositions not previously named are “Port Athol;” “Port Gordon;” and “Port Lennox.”

It is a curious coincidence that after spending many years with McLeod, of Dunvegan, in the Isle of Skye, O’Cahan should die at Eglinton Castle about the year 1653. In some inaccountable way during his long sojourn in Scotland he became known as Rory Dall Morrison, and this has so clouded his origin and identity as to involve his very nationality in question.

JOHN AND HARRY SCOTT

Contemporary with Rory Dall O'Cahan were the above named brothers, natives of the County Westmeath. Bunting says they were particularly distinguished for their caoinans or dirge pieces. They composed pathetic lamentations for Baron Purcell of Loughmoe, County Tipperary, and for Baron O’Hussey of Galtrim, County Meath.

GERALD O'DALY

The reputed authorship of “Eibhlin a Ruin,” is all that has preserved O’Daly's name from oblivion. Even his name is in dispute. In Bunting’s Ancient Music of Ireland; Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians; and British Musical Biography; the name is given as above; while in The Gentleman's Magazine, 1827; Hardiman’s Irish Minstrelsy, 1831; and in Fitz Gerald’s Stories of Famous Songs, 1906; it is Carrol O’Daly.

All, however, agree in associating the name with the famous melody.

Bunting, who refers to him as a contemporary of O’Cahan, who died in 1653, is of the opinion that from the marks of high antiquity apparent throughout the air, it is probable that he only adapted the Irish words to it. On the other hand Fitz Gerald tells us that at a venture he would suggest about 1450 when living money was still in use, as the probable date of the song, for the hero says ; he would spend a cow to entertain his ladylove.

The date of his death is given as 1405 by Mrs. Milligan Fox in her Annals of the Irish Harpers.

The earliest printed version of the song appeared on Coney's Beggar's Wedding, 1728 or 29. The song with music followed in 1731.

THOMAS O’CONNELLAN

This bard and musical genius whom Arthur O'Neill called “Tom Conlan, the great harper,” was born at Cloonmahon, (anciently known as Clonymeaghan), County Sligo. The date of his birth is variously given as about 1625 and 1640.

His celebrity in Ireland was very great although it would seem he was no less popular in Scotland where according to Arthur O'Nei11 he attained to city honors as “baillie” in Edinburgh. After a sojourn of a score of years in Caledonia, he returned to his native land in 1689 and died while a guest at Bouchier Castle, near Lough Gur in County Limerick in 1698. “His remains were reverently interred in the adjoining churchyard of Temple Nuadh,” Grattan Flood says, “and over his grave a few pipers appropriately played by way of a funeral dirge the introductory and concluding phrases which O'Connellan had added to Myles O’Reilly’s “Irish Tune;” the version being known as “The Breach of Aughrim,

A banshee we are told wailed from the top of Carrig na g-Colur while his funeral procession was passing to the burial ground. The mournful cooing of the wild pigeons from which the rock takes it name, may account for this quaint fancy.

The “Great Harper” was the composer of “The Dawning of the Day;” also known as “The Golden Star;” “Love in Secret;” “Bonny Jean;” “The Jointure;”“Molly St. George”, “If to a Foreign Clime I Go;” “Planxty Davis;” and seven or eight hundred others now forgotten. The last named: Planxty Davis, is known in Scotland as “The Battle of Killierankie.”

“By Lough Gur's waters, lone and low the minstrel’s laid-

Where rnouldering cloisters dimly throw sepulchral shade.

Where clustering ivy darkly weeps upon his bed,

To blot the legend where he sleeps - the tuneful dead!

And fallen are the towers of time, in dust in lone,

Where the ringing of his fairy chime, so well was known!

Where song was sweet and mirth was high, and beauty smiled

Thro’ roofless halls the night winds sigh, the owl shrieks wild.’

LAURENCE O’CONNELLAN

who is referred to by some writers as William, was a younger brother of the renowned harper and composer, Thomas O’Connellan. Born in the same home the difference in their ages is said to have been five years.

Laurence, who affected a different style from his more famous brother, produced many pieces of high merit. Among them are mentioned “Lady Iveagh;” “Saedbh Kelly;” and “Molly MacAlpine,” otherwise known as “Molly Halfpenny” and “Poll Ha’penny,” as a dance tune. It will be remembered that “Molly MacAlpine” was the air to which Tom Moore sung, “Remember the Glories of Brian the Brave.”

After the death of his elder brother, Laurence went to Scotland, bringing with him and popularizing several of the deceased minstrel’s compositions, among them being, according to James Hardiman, author of Irish Minstrelsy , `Planxty Davis,’ since well known as the 'Battle of Killicrankie,' and also a prelude to the “Breach of Aughrim” universally admired under the name of `Farewell to Lochaber.”

JOHN MURPHY

Arthur O'Neill, who may be regarded as the historian of the harpers, told Bunting of a famous harper named Murphy, a Leinster man, the son of a very indifferent performer, who had borne a higher reputation as a performer, than any other harper who had been O’Neill’s contemporary. On his return from the continent in 1719, after a stay of eleven years, his conceit was insufferable. He had played with approbation before Louis XIV.- Louis le Grand - of France, and proud of this distinction he assumed airs and ostentations finery, which naturally aroused the jealousy and ill-will of his professional brethren. The father on learning of his son’s arrival in Dublin in great grandeur promptly called on him, only to be kicked down stairs, for his shabby appearance. On another occasion O’Carolan, notwithstanding his blindness, nearly beat him to death in a tavern at Castle Blayney, County Monaghan. Murphy in his lofty impudenc sarcastically alluded to the Bard’s compositions as being but “bones without beef.” O’Carolan attacked him, and as he was screaming with pain and terror his irate assailant kept shouting into his ear, “Put beef to that air you puppy!” with every kick. The interference of onlookers saved the egotist's life.

In his Story of the Harp Grattan Flood says, that Murphy as harp solist, was one of the attractions at a special performance on February I4th, 1738 - the year in which O'Carolan died - at Smock Alley Theatre, Dublin. His death took place in 1753 after several seasons’ playing at Mallow, County Cork, then a popular health resort.

CORNELIUS LYONS

This renowned musician, who in his day was household harper to the Earl of Antrim, was a native of County Kerry, and nourished in the latter part of the seventeenth, and the early part of the eighteenth centuries.

Agreeable in personality, his reputation both as a man and a musician was admirable. Though a rival in art and even in composition, Lyons was O’Carolan;s loyal friend and companion. Famous as an arranger of variations in more modern style to such airs as “Eileen a Roon ;” “The Coolin”, etc., only one of his original compositions - ”Miss Hami1ton” - has been preserved.

The Earl of Antrim was a wit and a poet, and notwithstanding his rank, was quite democratic in his manners. Once while in London accompanied by Lyons, they went to the house of a famous Irish harper named Heffernan, who kept a tavern there, but agreed on a plan before entering.

“I will call you cousin Burke,” said his lordship. “Yon may call me cousin Randall or My Lord as you please.” It was not long before Heffernan was made aware of the dignity of his guest, from the conversation and livery of his 1ordship’s servants. Heffernan being requested to bring his harp complied willingly and played a good many tunes in grand style. The Earl then called upon his “Cousin Burke” to play a tune. After many apologies and with apparent reluctance the supposed cousin at length took the harp and played some of his best airs. Heffernan after listening a while started up and exclaimed, “My lord you may call him 'Cousin Burke’ or what cousin you please, but Dar Did he plays upon Lyons’ fingers.”

MR. HEFFERNAN

The above described episode was the first meeting of Lyons and Heffernan. Lord Antrim then retired, leaving the minstrels to enjoy themselves to their hearts' content which Arthur O’Neill assures us they did like “bards of o1d.” The story of the trick which had been played on Heffernan soon gained circulation and it was not long before the Duke of Argyle came to the tavern with a large company to hear him play. Unheeding his lordship's call for a Scotch tune Heffernan played “The Golden Star,” a plaintive Irish melody.

When the nobleman complained that it was too melancholy for a Scotch tune the harper replied, “Yon must know my Lord it was composed since the Union.” The remark touched a sensitive spot, for the Duke, who was an advocate of the Union of Scotland with England, hastily left the tavern with his company in no pleasant frame of mind.

MR. MAGUIRE.

A celebrated harper named Maguire, from the County of Fermanagh, settled in London about the year 1720, and opened a wine shop or tavern near Charing Cross. His house attracted the patronage of some of the very best people in the city, including the Duke of Newcastie and several of the ministry. On one occasion he was asked why the Irish airs were so plaintive and solemn. He replied that the native composers were “too deeply distressed at the situation of their country, and her gallant sons to compose otherwise; but remove the restraints which they labor under, and you will not have reason to complain of the plaintiveness of their notes.”

He had committed the impardonable sin! The expression of such warm sentiments of patriotism gave offence, his house became gradually neglected,- in modern idiom, boycotted - and he died broken-hearted a year or so afterwards.

OWEN KEENAN

Born in 1725 and therefore contemporary with Echlin O’Cahan, a harper named Owen Keenan, of Augher, was no less reckless, turbulent, and adventurous. Becoming enamored of a French governess at the residence of Mr. Stuart at Killmoon near Cookstown, County Tyrone, which he often visited, he proved that love laughs at other obstacles no less than at locksmiths. Blind as he was the impetuous Romeo made his way to the room of his Juliet by means of a ladder from the outside. This breach of the proprieties resulted in his commitment to Omagh jail.

Another blind harper named Higgins hailing from Tyrawley, County Mayo, who traveled in better style than most others of the fraternity, hearing of Keenan's predicament, hastened down to Omagh, where his respectable appearance and retinue readily procured his admission to see his friend. The jailer was not at home but his wife was. She loved music and cordials and being once a beauty was by no means insensible to flattery even from men who could not see. She fell an easy victim to their wiles, and the blind harpers contrived to steal the keys out of her pocket, oppressed as she was with love and music,

They did not forget to make the turnkey drunk also, and while Higgins remained behind soothering his infatuated dupe, Keenan escaped with Higgins’ boy on his back to guide him over a ford in the river Strule, by which he took his ,,, back to Kilmoon and repeated the offense for which he had been previously imprisoned.

After narrowly escaping conviction at the County assizes, Keenan finally carried off the governess and married her. Seldom does an affair of this kind end otherwise than happily in the story books, yet rumor compels us to add that after their emigration to America, the fickle French woman proved unfaithful to her romantic Romeo.

HUGH O'NEILL

An honorable exception to the generality of`the harpers of his day Hugh O’Neill was a man of conspicuous respectability both in character and descent.

He was born at Foxford, County Mayo, late in the seventeenth century, and his mother being of the MacDonnell family, was a cousin to the famous Count Taaffe.

Having lost his sight by smallpox when but seven years old, he devoted himself to the study of music as an accomplishment. In later years this acquirement was turned to good account when he was beset with reverses of fortune.

From the respectability of his family and the propriety of his deportment, he was received more as a friend and associate than a professional performer by the gentry of Connacht.

To the generosity of Mr. Tennison of Castle Tennison, County Roscommon, he owed the possession of a large farm at a nominal rent. Though sightless he enjoyed a hunt with the hounds which in an open country like Roscommon subjected him to comparatively little physical danger.

JEROME DUIGENAN

\Ve are indebted to Arthur O’Neill, the Plutarch of the harpers, for all that is known of this remarkable performer on the harp, who was born in County Leitrim in the year 1710.

“There was a harper before my time,” he says, “named Jerome Duigenan, not blind, an excellent Greek and Latin scholar, and a charming performer.” Of the numerous anecdotes heard by O’Neill concerning him, that which pleased him most was the following:

Duigenan lived with a Colonel Jones of Drumshambo, who was one of the representatives in parliament for the County of Leitrim. The Colonel being in Dublin at the meeting of parliament, met with an English nobleman, who had brought over a Welsh harper. When the Welshman had played some tunes before Colonel Jones which he did very well, the nobleman asked him had he ever heard so sweet a finger. “Yes,” replied the Colonel, “and that by a man who never wears either linen or woolen.”’ “l’ll bet you a hundred guineas” says the nobleman, “you can't produce anyone to excel my Welshman” The bet was accordingly made, and Duigenan was written to and ordered to come on immediately to Dublin and bring his harp and dress of Cauthach with him; that is a dress made of beaten rushes, with something like a caddy or plaid of the same stuff. `On Duigenan’s arrival in Dublin the Colonel acquainted the members with the nature of his bet, and they requested that `it might be decided in the House of Commons before business commenced. The two harpers performed before all the members accordingly, and it was unanimously decided in favor of Duigenan, who wore his full Cauthach dress, and a cap of the same stuff shaped like a sugar loaf with many tassels. He was a tall handsome man and looked well in it. Mr. Bunting says this conical cap was unquestionably the barradh of the old bards, and corresponds with the costume of the head carved on the extremity of certain ancient Irish harps.

DOMINIC MUNGAN

A harper of great renown in the first half of the eighteenth century was Dominic Mungan, whose story Edward Bunting learned from Henry Joy, Esq., of Belfast, who often heard him play.

Born blind about the year 1715 in the pastoral and poetical county of Tyrone, his profession was determined by his affliction, and in it he acquired such fame as to embalm his name in the annals of Irish musical literature. He was long famous for his excellent performance throughout the north of Ireland “where he regularly went the Northwest circuit with the bar.” An admirable performer, those janglings of the strings so general among ordinary praetitioners were never heard from the harp in his hands. His “whispering notes,’ were indescribably charming. They commenced in a degree of Piano that required the closest approach to the instrument to render them audible, but increased by degrees to the richest chords.

Mungan was conversant with the best music of his day such as that of Corelli, Handel, and Geminiani, select adagios from which he often played.

Being a man of prudence and economy he was enabled to give his three sons a liberal education. Mark, the eldest, destined for the priesthood finished his studies in France where he obtained more than two score premiums for classical learning. In consequence of his intense application his health failed on his return home, and he died at Strabane in his father’s house.

John, the second son, becarne a physician and won distinction in his chosen profession, abandoned the creed of his parents, and lost his life in an accident returning from the Middleton races.

The youngest son, Terence, also apostatized, and was appointed dean of Ardagh, from which he was promoted to the bishopric of Limerick in the Established Church.

John the doctor had fallen in love it is said with a protestant young lady, who refused his suit on account of his creed. Having recanted he again sought her hand, and was scornfully rejected. She “would not demean herself by marrying a turncoat.” To add still further to his humiliation his father refused to speak to him thereafter.

ECHLIN O'CAHAN [ACKLAND KANE]

Strong as the wandering proclivities of the Irish harpers have been for centuries prior to their extinction, it is doubtful if any of them indulged this propensity to such an extent as did the subject of this sketch, who was born at Drogheda, County Louth in 1720.

Such was his love of adventure, that notwithstanding his blindness, he visited Rorne early in life where he played before “the Pretender,” then resident there. In his subsequent travels through France and Spain in which a large number of exiled Irish had settled, he was treated with great liberality and introduced to the notice of His Catholic Majesty. The design of favoring him with a pension which the king had in contemplation, was frustrated by his own indiscretions, and after exhausting the patience and patronage of his countrymen at Madrid, O'Cahan set out on foot for Bilboa on his way home, carrying his harp on his back. As he was a very strong, athletic man he reached his destination safely.

It does not appear that he spent much time in Ireland after his return, for all mention of his name and fame thereafter down to the time of his death in 1790 is in relation to Scottish events.

While on a tour of the Isles in 1775, he was at Lord Macdohald’s of Skye, where he recommended himself so much by his performance, that his host presented him with at silver harp key that had long been in the family, “being unquestionably,” Bunting says. “the key left by his great predecessor and namesake, Rory Dall O'Cahan.” But the dissipated rascal sold it in Edinburgh and drank the money.

His behavior was not at all times so exemplary, for Mr. Gunn relates that the Highland gentry occasionally found it necessary to repress his turbulence by clipping his nails; thereby “putting him out of business” for a time.

His execution and proficiency were a credit to his teacher, Cornelius Lyons, harper to the Earl of Antrim. Manini often spoke of him at Cambridge with rapture, as being able though blind, to play with accuracy and great effect the fine treble and bass parts of many of Corelli’s concerts, in concert with other music. Had he been but moderately correct in his conduct he might with certainty have raised the character of the wandering minstrel higher than it had stood for a century before.

THADY ELLIOTT

In deseribing harpers ot note we would hardly be justified in ignoring Thady Elliott of County Meath, the blind minstrel, who taught Rose Mooney.

His general character, though spoken of disparagingly by Edward Bunting, was viewed with more Iiberality and toleration by Arthur O’Neill, who experienced nothing but kindness at his hands.

Elliott's chief claim to fame or rather notoriety, rests on an act bordering on sacrilege which but few outside of Bedlam would have the hardihood to attempt.

A practical joker of a type not yet extinct, knowing that he was to play at the celebration of Mass on Christmas morning at the town of Navan, took him to a public house or tavern the evening before. and bribed him with the promise of a gallon of whiskey to strike up “Planxty Connor,” one of O’Carolan's lively tunes, at the time of the Elevation.

With all due decorum Thady played sacred music until the appointed time, when true to his word, he swung into “Planxty Connor” to the horror of the officiating priest who well knew the apocryphal nature of the melody.

Other means of showing his displeasure being unavailable, the priest repeatedly stamped his foot. Some who thought his emphatic movement was but an irresistible response to Thady's spirited strains, whispered “Dhar Dhia tha an Sagart ag Rinnce.” The daring and irreverent harper after a few rounds of the Planxty resumed the sacred airs, but that didn’t save him from denunciation and dismissal after the service.

A harper named Harry Fitzsimmons, who was engaged to play at the later Masses, had no easy time of it, escaping Elliott’s vengeance. The latter though blind, secured a club and laid in wait outside the chapel door for his intended victim. After a while some one seeing the priest coming out said “Ta se ag teact” (He is coming). When the footsteps indicated striking distance Thady made a sweeping blow which, had it hit his reverence instead of the chapel door, would have seriously injured him.

Humiliated like the lion who loses his prey by miscaleulating the length ai his spring, Thady Hlliott re-entered the sanctuary and publicly apologized for his misbehavior.

He was born in 1725, and notwithstanding his vices and his follies, Bunting says he was a capital performer, and generous and hospitable in the highest degree.

“OLD” FRENEY

Mingled with mother earth in some ancient church yard in his native province, for more than a century, lie the mortal remains of “Old Freney the Harper”, described in The Dublin Penny Journal of October 20, 1832.

Freney or Frene, as he was sometimes called, was not less than ninety years old at the end of the eighteenth century. Of medium size and bent with age, his head of Homerie cast was crowned with hair of the whitest, and he was a welcome visitor in every respectable family in many of the western counties. His harp, as the writer could recollect its oppearanee was a dark framed antique looking instrument, closely strung with thin brass wires, which produced that wild, low ringing music poetically compared to the “ringing of fairy chimes.” The effect of this was heightened by the old ma's peculiar expression of intense and sometimes pleased attention to his own music as` he stooped forward. Holding his head close to the wires, as he swept them over with a feeble, uncertain and trembling hand - the too obvious effect of extreme age. His appearance thus bowed beside the instrument, which towered far above his white head. was of the most picturesque character. But the old minstrel had no rallying of tuneful power - his harp strings seemed to have caught the wandering, querulous and feeble dotage of his infirm age and echoed mournfully of departed power and life.

It now adds much to the interest of his memory, that he could not have been the welcome guest, which at that time he was for the sake of his music alone. He was a venerable ruin of those good old times which were felt to he passing away with the harper. 'Old’ Freney had lived among their granffathers, and had been prominent in the gay doings of those less refined, but more joyous and hospitable times. He was full of old stories about persons whose names and deeds had still an interest in the memory of their descendants; and those stories were listened to with a delight which can now be little understood.