TURLOCH O'CAROLAN AND HIS TIMES

To do anything like reasonable justice to such a celebrity as the great Irish Bard in a few pages is a hopeless task. And what adds to the difficulty is, not the lack but rather the amplitude of material available. Nothing less than a good-sized volume would meet the requirements.

Turlogh O'Carolan was born about the year 1670 at a place called Baile Nuadh or Newtown, near Nobber in the County of Westmeath, but in his youth his father migrated to County Leitrim, where he settled on a farm near Carrick-on-Shannon. Though gifted with a natural genius for music and poetry he displayed no precocious disposition for either. Had he not lost his sight when 10 or 15 years of age from an attack of smallpox, it is doubtful if he would ever have won undying fame through his minstrelsy. Accident or rather chance determined his vocation, and he continued it more by choice than necessity. Respectably descended, possessing no small share of Milesian pride, and entertaining a due sense of his additional claims as a man of genius, he neither played for hire nor refused a reward if offered with delicacy, and he always expected and invariably received that attention which he deserved. His visits were regarded as favors, and his departure never failed to occasion regret. He seldom extended his travels beyond the province of Connacht, where he was such a universal favorite, that messengers were continually after him to one or other houses of the principal inhabitants; his presence being regarded as an honor and a compliment.

Instinctively understanding that hospitality has its limitations, he made a good natured reply of which the following is a translation, to a gentleman who was pressing him to prolong his stay.

“If to a friend’s house thou shouldst repair;

Pause and take heed of lingering idly there;

Thou mayest be welcome but it’s past a doubt;

Long visits soon will wear the welcome out.”

In his Historical Memoirs of the Irish Bards; Walker says O’Carolan must have been deprived of sight at a very early period of his life; for he remembered no impression of colors. His merry saying: “My eyes have been transplanted into my ears,” does not necessarily imply early blindness. Other authorities mention sixteen, and eighteen years respectively, as his age when afflicted, while Grattan Flood extends the date to his twenty-second year.

“He was unquestionably a great genius both as a composer and a poet; but it is equally certain that he never excelled as a performer,” according to Edward Bunting: “This may be attributed to the fact that he did not begin to learn the harp till he was upwards of sixteen at which age the fingers have lost the suppleness that must be taken advantage of in early years, to produce a really master hand.”

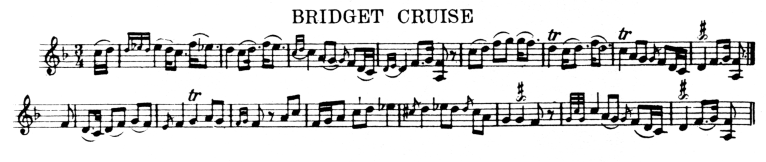

Love does not always enter at the eyes for O'Carolan became enamored of Miss Bridget Cruise of Cruisetown in County Longford several years after he had lost his sight, and though this lady did not reciprocate his affection; yet the song in which her name is immortalized is regarded as his masterpiece coming as it did, warm from his heart while his genius was in its full vigor.

Near his father’s house was a rath, in the interior of which one of the Fairy Queens or “good people’, was believed by the country people to hold her court. This rath or fort was the scene of many a boyish pastime with his youthful companions; and after he became blind, he used to prevail on some of his family or neighbors to lead him to it, where he would remain for hours together, stretched listlessly before the sun. He was often observed to start up suddenly, as if in a fit of ecstasy, occasioned as it was firmly believed by the preternatural sights which he witnessed. In one of these raptures he called hastily on his companions, to lead him home, and when he reached it, he sat down immediately to his harp and in a little time played and sung the air and words of a sweet song addressed to Bridget Cruise, the object of his earliest and tenderest attachment.

So sudden and so captivating was it, that it was confidently attributed to fairy inspiration. From that hour he became a poet and composer. “Bridget Cruise,’ is the only one of O’Carolan's airs composed in the traditional style.

One of his earliest patrons, George Reynolds of Letterfian Leitrim, who was something of a poet himself, remarked to O’Carolan in the Irish idiom: “Perhaps you might make a better hand of your tongue than of your fingers.” He suggested a text by telling him that a great battle had been recently fought between the fairies or “good people’, of two hills in the neighborhood. The influence of the folklore of his boyhood and the day dreams in which he indulged at the rath, contributed not a little to the inspiration which produced “The Fairy Queens” in 1693, a much more ambitious composition than “Bridget Cruise.” No more successful in his courtship of Margaret Browne - the “Peggy Browne” of his muse - than of Miss Cruise, he consoled himself with the charms of Mary Maguire, a young lady of good family in the County of Fermanagh, whom he married in his fiftieth year. Though she was proud and extravagant they lived in connubial harmony through life. After his marriage he occupied a small farm near Mohill in County Leitrim, but hospitality more suited to his mind than his means, soon caused embarrassment, and he was soon left to lament the want of prudence without which the rich cannot taste of pleasure long, nor the poor of happiness.

Equipped with a good horse and an attendant harper furnished by his generous patroness and lifelong friend. Mrs. MacDermott Roe of Alderford House, County of Roscommon, O'Carolan commenced the profession of an itinerant harper or bard in 1693. Wherever he went the gates of the nobility and others were thrown open to him; he was received with respect and a distinguished place assigned him at the table. In all respects he was a genuine representative of

the bards of old.

It was during his peregrinations that he composed all of the two hundred airs which have immortalized his fame. He thought the tribute of a song (with music of course) due to every home in which he was entertained, and he seldom failed to pay it: choosing for his subject either the head of the family or the loveliest of its branches.

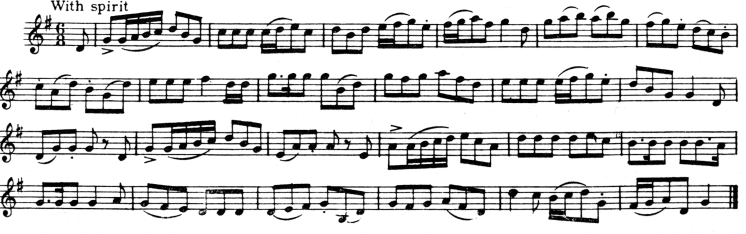

THE FAIRY QUEENS

One of O’Carolan’s earliest friends was Hugh MacGauran, a County Leitrim gentleman, who had a happy poetic talent, and excelled particularly in ludicrous species of poetry. He was the author of the justly celebrated song of Plearca na Ruarcach freely translated as “O'Rourke's Feast,” which he prevailed on the bard to set to music. The fame of the song having reached the ears of Dean Swift, he requested of MacGauran a literal translation of it in English. The Dean was so charmed with its beauties that he honored it with an excellent version of his own. MacGauran's original composition in Irish appears to have been lost, but O'Caro1an's “Planxty O'Rourke” composed about 1721, has been preserved.

PLANXTY O'ROURKE (O'Rourke's Noble Feast)

Although O'Carolan delivered himself but indifferently in English, he did not like to be corrected for his solecisms, Hardiman tells us in his Irish Minstrelsy. A humorous instance of this weakness has been handed down. A self sufficient gentleman surnamed O'Dowd or Dudy, as it was sometimes pronounced, once criticising his English, asked him why he attempted a language ot which he knew nothing. “Oh I know a little of it” was the reply. “If so,” said the egotist, “can you tell me the English for Bundhoon?”“Yes,” said the bard with an arch smile, “I think the properest English for that word is Billy Dudy.” This grotesque repartee turned the laugh against the critic who was ever after nicknamed “Billy Bundhoon.” .

O’Carolan seldom exercised the keen satirical powers he possessed, although occasionally they were aroused by inhospitality - to him the only unpardonable sin. At the house of a parsimonious lady who was sparing in her supply of O’Carolan’s favorite beverage, a butler named O'Flynn, who objected to his freedom of the wine cellar - a customary privilege - had his name preserved from oblivion in the couplet-

“What a pity hell's gates are not kept by O’Flynn! So surly a dog would let nobody in.”

The incident which led to the birth of “O'Carolan's Devotion”, was a chance meeting with a Miss Featherstone of County Longford, who was on her way to church at Granard one Sunday in the year 1719.

“Your servant. Mr. O'Caro1an,” she saluted.

“I thank you. Who speaks to me?” he replied.

“It is I, sir. One Miss Featherstone.”

“I've heard of you, Madam: a young lady of great beauty and much wit. The loss of one sense prevents my beholding your beauty; and I believe it is a happy circumstance for me, for I am assured it has made many captives. But your wit, Madam! I dread it.”

“Had I wit, Mr. O’Carolan, this is not a day for its display. It should give place to the duty of prayer. I apprehend that in complying with this duty, you go one way, and I go another -I wish I could prevail with you to quit your way for mine.”

“Should I go your way, Madam, I dread you yourself would be the chief abject of my devotion.”

After some bantering of this nature, Miss Featherstone invited the bard to visit her house, assuring him of a hearty welcome, and admonishing him to pray for her at his church. Very gallantly O’Carolan responded: “Could I withdraw my Devotion from yourself, I would obey; but I will make the best effort I can. Adieu. Adieu.”

“Adieu to you, O'Carolan 0 but remember--”

The event justified his fears. Instead of praying for Miss Featherstone, he neglected his religious duties to compose a song on her, which has been described as “humorously sentimental, but in bad English.” The music, however, was of a high order.

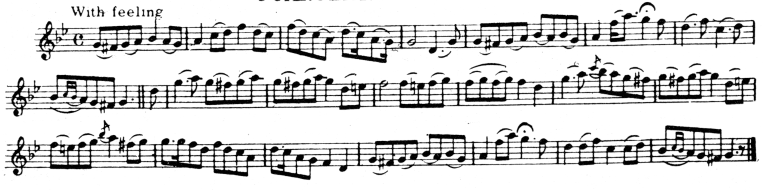

O'CAROLAN'S DEVOTION

Irish hospitality and his mode of life led to his fondness for the “flowing bowl,” as it does almost invariably with his humble brethren of the present day.

Inordinate gratifications bring their own punishment, and from the consequence O'Carolan was not exempt. Physicians assured him that unless he corrected his habits, his mortal career would soon come to an end. He determined to abstain thereafter from the forbidden yet delicious cup. He wandered about the town of Boyle, County Rosconnnon, at that time his principal residence, dejected in spirit and brooding in melancholy. His gayety had forsaken him, and his harp lay in some obscure corner of his habitation, neglected and unstrung.

Passing one day by a grocer’s shop, our Irish Orpheus, after a six weeks' quarantine, was tempted to step in, undecided what course to pursue. “Well, my dear friend,” cried he to the young man who stood behind the counter, “you see I am a man of constancy; for six long weeks I have refrained from whiskey. Was there ever so great a case of self-denial? But a thought strikes me, and surely you will not be cruel enough to refuse one gratification which I shall earnestly request. Bring hither a measure of my favorite liquor, which I shall smell to, but indeed shall not taste.” The lad indulged him on that condition; and no sooner did the fumes ascend to his brain than every latent spark within him was rekindled. His countenance glowed with an unusual brightness, and the soliloquy which he repeated over the cup was the effusion of a heart newly reanimated. Contrary to the advice of his medical friends, he once more quaffcd the forbidden draught until his spirits were sufficiently exhilarated and his mind had resumed its former tone. Inspiration returned, and he immediately set about composing that much admired song known as “O’Caro1an's Receipt,” or “Planxty Stafford.” That same evening, at Boyle, he commenced the words and began to formulate the air, and before the following morning he sang and played this noble offspring of his imagination in Mr. Stafford’s parlor at Elphin.

O'CAROLAN'S RECEIPT FOR DRINKING (Planxty Stafford)

When O’Carolan was enjoying the hospitality of Thomas Morris Jones, Esq., of Moneyglass, County Leitrim, in the year 1730, he signalized the occasion by composing a song, according to his custom. While so engaged he was overheard by one Moore, who had a ready ear for music and played tolerably well on the violin. After completing his inimitable piece, O’Carolan proudly announced that he had now struck out a melody which he was sure would please the Squire.

Moore, in a spirit of mischief, insisted the air was an old and common one. And to prove his contention he actually played it note for note on the violin. This, of course, threw the bard into a rage. However, when his passion calmed down, an explanation took place, and all misunderstandings were duly drowned in the good old-fashioned way.

Another version of this story is to the effect that O’Carolan and Baron Dawson happened to be enjoying, with others, the hospitalities of Squire Jones, and slept in adjoining rooms. The bard being called upon by the company to compose a song or tune in honor of their host, retired to his apartment, taking his harp with him, and under the inspiration of copious libations of his favorite beverage, not only produced the melody now known as “Bumper Squire Jones,” but also very indifferent words to it. While the bard was thus employed, however, Baron Dawson was not idle. Being possessed of a hne musical ear as well as considerable poetical talents, he not only fixed the melody in his memory, but actually wrote the noble song now incorporated with it before he retired to rest.

At breakfast the following morning, when O'Carolan sang and played his composition, the Baron, to the astonishment of all present, and the bard in particular, stoutly denied O’Carolan's claims to the melody, and to prove his contention, sang it to his own words amid shouts of laughter and approbation. The bard, whose anger knew no bounds, was eventually mollified by explanations.

Not few were the practical jokes of a similar character that had been perpetrated on the blind bard in his time.

All accounts of O’Carolan's life make mention of a romantic incident which occurred about 171,3 during his pilgrimage to “St. Patrick’s Purgatory” in an island in Lough Derg, County Donegal. On his return to shore he found several pilgrims awaiting the arrival of the boat which had conveyed him to the penitential cave. In assisting some ot those devout pilgrims to step on board, he chanced to take a lady’s hand, and instantly exclaimed: “Dar lamha mo chardais Criost” (by the hand of my gossip), “this is the hand ot Bridget Cruise.” His sense of feeling did not deceive him; it was the hand of her whom he had adored - his first love.

His musical capacity had been severely tested more than once when the craze for Italian music had crossed the Channel from England, but he never failed to acquit himself with credit.

The story goes that an Italian voilinist named Geminiani, then residing in Dublin, hearing of O'Carolan’s fame, took steps to put it to the proof. Selecting an elegant piece of music in the Italian style, he altered it here and there in such a manner that none but a keen musician could detect the mutilation, and sent it to the hard at Elphin, County Roscommon. The latter, on hearing it played, declared it to be a nne piece of music, but humorously remarked in Irish: “Ta se air cois air bacaige?”

He rectified the errors as requested, and when the music score was returned to the Italian maestro in Dublin, he pronounced O'Carolan to be a true musical genius.

On another occasion, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, according to the historian Sylvester O'Halloran, the then Lord Mayo brought from Dublin the celebrated Geminiani to spend some time with him at his seat in the county. O'Carolan, who happened to be visiting his lordship at the same time, found himself greatly neglected, and complained of it one day in the presence of the foreigner. “When you play in as masterly a manner as he does,” replied his lordship, “you shall not he overlooked.” O’Carolan, whose pride was aroused, wagered with his rival that though he was almost a total stranger to Italian music, yet he would follow him in any piece he played, and he himself would afterwards play a voluntary in which the Italian could not follow him. The test piece happened to he Vivaldi's fifth concerto, which the foreigner played on the violin. The blind bard was victorious, and “O’Caro1an's Concerto” was the result.

The death of his wife in 1733, which was his first bereavement, threw a gloom over his mind, that was never after entirely dissipated. Realizing that the sands of his life were fast running out, he commemorated his final departure from the hospitable home of his great friend, Robert Maguire of Tempo, County Fermanagh, with the production of that plaintive melody, “O’Carolan's Farewell.”

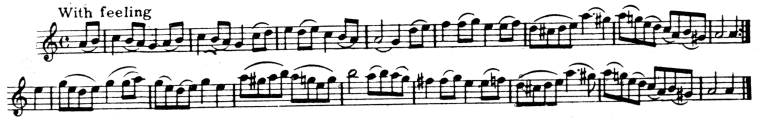

O'CAROLAN'S FAREWELL

Hastening on his way and making a few hurried visits to cherished friends in County Leitrim, he reached his destination - Alderford House - the residence of his lifelong friend, Mrs. McDermott Roe, where he died on the 25th of March. 1738, in the sixty-eighth year of his age. Shortly before his death, he called for his harp, and with feeble fingers wandering among the strings, he evolved his last composition, the weirdly plaintive wail, “O’Carolan's Farewell to Music.”

O'CAROLAN'S FAREWELL TO MUSIC

O’Carolan's funeral was a memorable event. The wake lasted four days, and he was buried on the fifth, in the MeDermott Roe vault at Kilronan Ardagh, County Westmeath. Upwards of sixty clergymen of different denominations, a number of gentlemen from surrounding counties, and a vast concourse of country people assembled to pay the last mark of respect to the great bard. Hospitality was lavish, a keg of whiskey on either side of the hall was replenished as often as emptied, and the music of the harp was heard in every direction.

During his forty-five years of itinerant minstrelsy, he is said to have composed upwards of two hundred pieces of music, many of which have been irretrievably lost, including all but one of the fifteen addressed to Bridget Cruise, the object of his youthful yet hopeless attachment.

A harper who attenueo the Belfast hard revival in 1792, and who had never met the bard, had acquired more than one hundred of his tunes, it is said. Although half a dozen or so of his productions had been included in J. And W. Neales Collection of Irish Times, in 1726, and at least as many more were printed in Wright's Aria di Camera, two years later, nothing purporting to be a collection of his compositions appeared until nine years after his death.

Under the patronage of Rev. Dr. Delaney of Dublin, O~Carolan’s son, who had little musical genius, published by subscription a small edition of his father’s works in 1747, but selfishly and unfilially omitted several of the best of them.

O’Carolan was the first of the Irish harpers who departed from the purely Irish style in composition. Bunting says he delighted in the polished compositions of the Italian and German schools, yet he felt the full excellence of the ancient music of his own Country.

Uniting in his person the fourfold avocations of his race - poet, composer, harper, and singer - he may well be regarded as the last true bard of Ireland; but he possessed none of their ruling spirit, for he was more festive than patriotic. Welcome alike to hall and cottage, he spent his days in cheering their inmates, as Bayle Bernard says, with his love songs and his planxties, and doubtless did so all the more in being himself the happiest harper who has ever repaid the loss of sight by the felicities of sound.

Though nearly two centuries have passed on the wings of time since Turlogh O’Carolan was “gathered to his fathers,” he still lives in his own deathless strains; and while the charms of melody hold their sway over the human heart, the name of the great Blind Bard will he remembered and revered. As a fitting conclusion to this brief biography, we quote the expressive words of Charles O’Conor of Belanagar, his loyal friend: “Turlough O'Carolan, the talented and principal Musician of Ireland, died. May the Lord have mercy on his Soul, for he was a moral and religious man.”