CHAPTER XIII

THE DEVELOPMENT OF TRADITIONAL IRISH MUSIC.

THE saying that the invention of writing injured the power of memory, finds much support from the fact that musicians ignorant of written music, possess the faculty of memorizing tunes to a far greater degree than those who acquire their repertory from that source.

We have all heard of Irish seanachies and professional story tellers of Oriental countries, who could recite hundreds of talcs and genealogies in identical phraseology from day to day and year after year. Neither historians nor those who read their works could hope to rival them in that respect.

Music it must he granted surpasscs every other aid to memory in that it brings its influence most directly and most movingly to the heart. The old song or strain possesses a power which will turn back the years oven to the cradle no less than the odor of forgotten flowers.

We must not forget however that memory is capricious, and preserves a battling independence of the will. We cannot always summon up forthwith the images or combination of tones which we desire. Neither can the untrained ear be always relied on when we wish to reproduce the words or musical forms casually impressed on it.

The bards, like their predecessors the druids, concealed with jealous care all knowledge from the vulgar eye. The harpers in their turn, Brompton, the English abbot, tells us, taught in secret and committed their lessons to memory before the Norman invasion - a practice they continued down throngh the centuries.

Neither harpers not pipers made use of printed music cvcn when available in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as in fact the majority of them were blind and of necessity obliged to learn and teach by the oral method only.

Musicians of talent, harpers principally, have exercised their skill in elaborating simple melodies, and adding variations to the original strains. All of the four dozen airs in Burk Thumoths collections published in 1742-1743, whether Irish. Scotch, or English, are embellished with variations; and the same can he said of popular Irish and Scotch airs in O'Farrell’s, Alday's, and other collections, down to the early years of the nineteenth century.

Fired by the same ambition, the pipers and fiddlers invoked their muse to emulate the example of the harpers and set about composing additional “parts” and florid finishes to their simple dance tunes, especially jigs, and before long it was nothing unusual to find a jig with from three to half a dozen “parts” or strains. Not a few had been enlarged to seven, eight, and nine parts. In O'Farrell's Pocket Companion for the Union Pipes (third collection about 1810), “The Little House Under the Hill” jig has no less than eleven “parts,” while a nameless long dance in the Petrie collections is extended to twenty-four parts! Though Bunting tells us that the harpers invariably played and transmitted their tunes precisely as they had been taught them, it is but reasonable to make some allowance for lapses of memory and individual taste: for even Bunting himself included in his later collections variants of airs he had previously printed under different titles.

Quite obviously memorized music disseminated from one generation to another by vocal or instrumental means would inevitably lead to the formation of many variants from original versions.

Traditional music unlike any form of modern composition is not the work of one man but of many. Indeed it can hardly be said to have been composed at all. It is simply a growth to a certain extent subject to the innnence of heredity, environment, natural selection, and the survival of the fittest.

It may be regarded as axiomatic that the older the melody the simpler the strain. Melodies consisting of bnt one strain are to be found in the Petrie and Joyce collections.

The purpose of this chapter is not so much the discussion of the subject, as the practical demonstration of the changes which time and taste have brought about in some pieces of Irish music, and how dance tunes particularly have been evolved from vocal airs and other forms of the same melody.

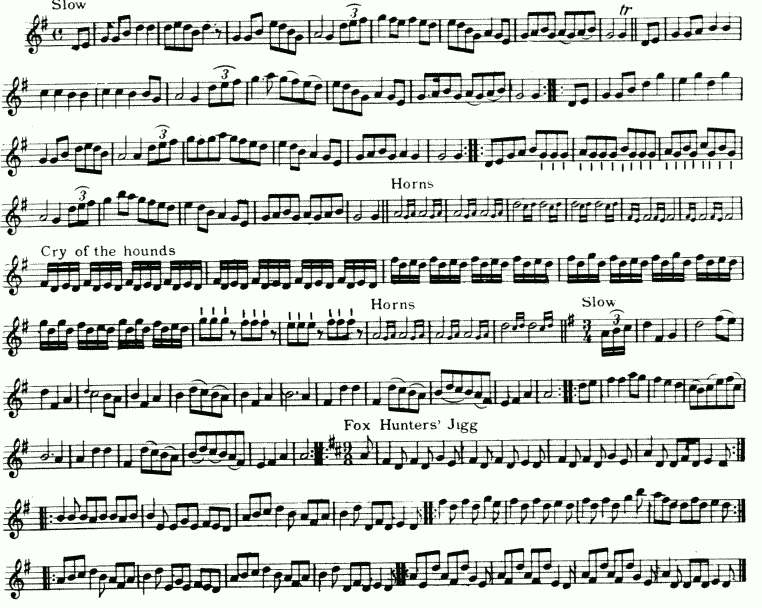

THE IRISH FOX HUNT, OR THE FOX CHASE

No piece of Irish music is so widely known by name in the land of its origin at least as “The Fox Chase.” As an instrumental composition it is attributed to Edward Keating Hyland, a celebrated blind piper who received some lessens in theory and harmony from Sir John Stevenson in Dublin. The melody or theme on which it was founded was an ancient lamentation to which was sung some verses in both Irish and English reciting a dialogue betwcen a farmer and a fox which he had detected with the “goods” on him in the shape of “a fine fat goose.”

From this air then called “An Maudrin Ruadh” (Modhereen Rus), Hyland developed the famous descriptive piece, including the sounds of the chase such as the tallyho, baying of the hounds, death of the fox, etc., and winds up the performance with “The Foxhunters' Jig”, an expression of the general delight at the result.

Fortunately we can present a copy of “The Irish Fox Hunt” as printed in O'Farrell's Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, published about 1806. This being but seven years subsequent to the date of its composition according to Grattan Flood, it can be safely assumed that O'Farrell's setting is authentic.

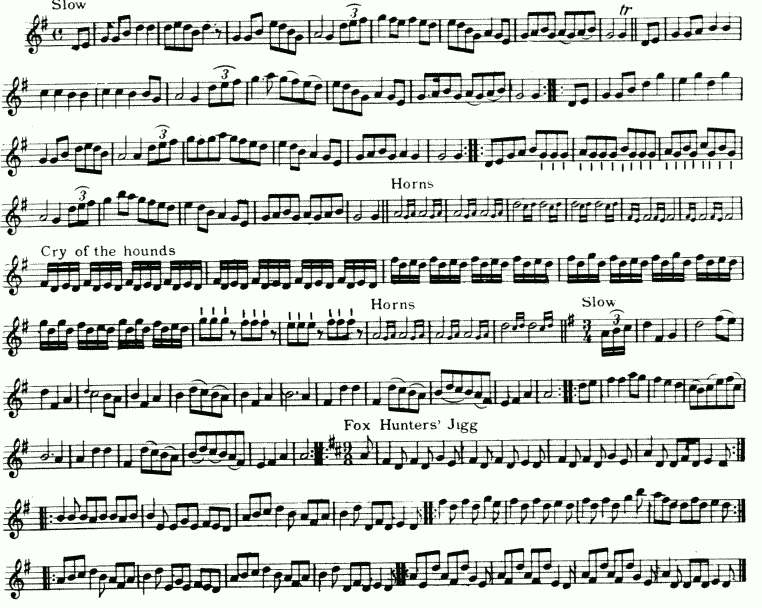

The next version, entitled “The Fox Hunt” is that found in the manuscript collection of Henry Hudson, 24 Stephens Green, Dublin, completed in 1842. A notation indicates that Mr. Hudson copied this and other tunes from an older collection owned by F. M. Bell.

Through the kindness of the princely Prof. P. J. Griffith of the Leinstcr School of Music we are enabled to submit the genial professor's own version of “The Fox Chase”, the version by the way which, enhanced hy his skillful execution, won the seal of supremacy at various contests.

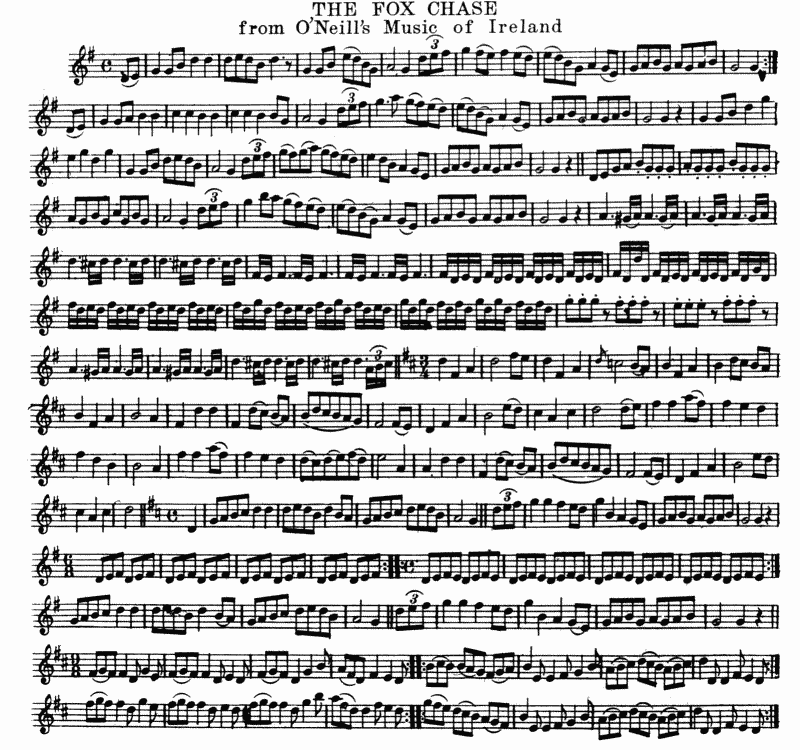

The fourth and final example of “The Fox Chase” is that which appears in O’Neill's Music of Ireland published in 1903. Although we had been led to believe that the setting was that played by the great Munstcr piper, Stephenson, it turns out that “Patsy” Touhey ohtained it from John L. Wayland at the Cork Pipers' Club, and that it primarily came from Mrs. Kenny of Dublin.

We trust the settings or versions of the once popular piece of music herein presented will serve to relieve the anxiety of several correspondcnts who feared that it would be utterly lost, although were it necessary several other versions could have been submitted.

THE IRISH FOX HUNT

from O'Farrell's Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes

Vol I Book 2 circa 1806

THE FOX HUNT

from H. Hudson's Manuscript Collection 1841 A. D.

THE FOX CHASE - Tipperary Version

by Prof. P. J. Griffith Dublin

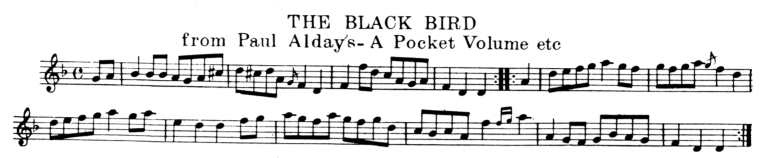

Deservedly popular whether as an air or dance tune in the late generations, “The Blackbird” was one of those allegorical songs much in vogue in the days of the “Old Pretender” in the beginning of the eighteenth century.

The earliest printed setting of this melody which we have been able to discover is that found in A Pocket Volume of Airs, Duets, Songs, Marches, etc., Vol. I, published by Paul Alday at Dublin about 1800-1803. Included among “Six Favorite Original Airs never printed till now” we find:

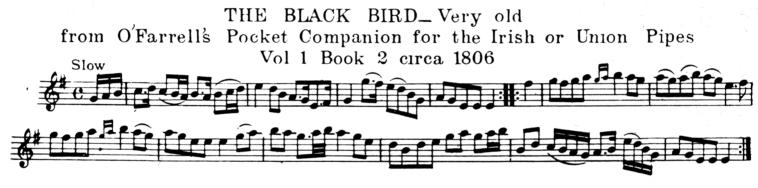

The following version was taken from O’Farrell’s Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, etc., published about 1806 and entitled:

It is indeed surprising to find that no setting or version of this noted tune can be found in the Petrie Collections of Irish music.

The setting of this melody which Bunting credits to “D. O’Donnell, harper, County Mayo”, although obtained in 1803, the same year in which Alday’s version was printed - was withheld until the publication in 1840 of The Ancient Music of Ireland, his third volume. This florid setting serves to illustrate what skillful instrumentalists can accomplish in the elaboration of the most simple compositions.

As Bunting’s version of “The Blackbird” with a traditional and long dance setting are included in Appendix C, of Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby, their reproduction in this work is unnecessary. Had we then possessed the ancient versions above presented they also would have been included in that work.

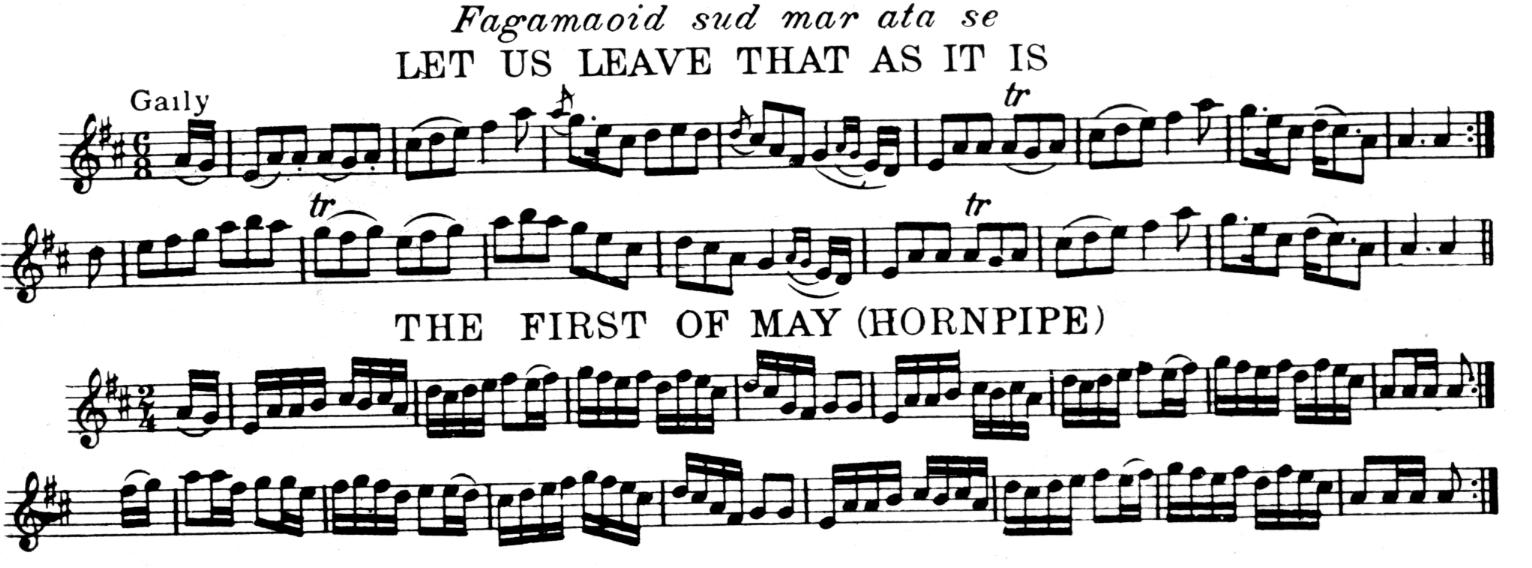

Fugamaoid sud mar ata se, and THE FIRST OF MAY

A prominent advocate of traditional Irish music who was enthusiastic in his praise of a hornpipe known as “The First of May” was asked if he considered it a very old tune. Unhesitatingly he replied that it was one of the very oldest. A brief discussion which followed gave the learned gentleman much food for thought for the evidence of its derivation from a much older melody was most convincing.

We can assume that no one will question the antiquity of the air called “Fagamaoid sud mar ata se.” By no means a rare melody, two settings of it being in the Complete Petrie Collection, Dr. Joyce, who includes a version of it in his Ancient Irish Music, says: “Several songs, both English and Irish, are sung to this air which is well known all over the Munster counties.” Many will remember that “Darby O’Leary,” or “The Galbally Farmer,” was one of them.

A comparison of the air which is in six-eight time, with the hornpipe in common time, will show that they are identical in strain and differ only in arrangement. Plainly enough, the hornpipe was evolved from the old air, as in many similar instances.

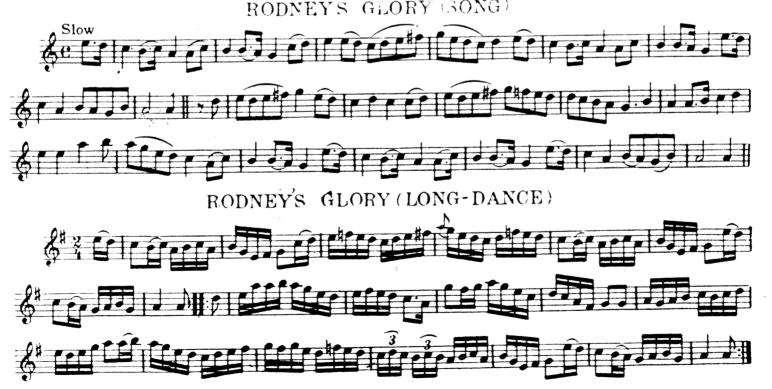

Rodney's Glory

Not the least popular of the long dance tunes of a generation or so ago, was “Rodney’s Glory.” In this form it is simply an adaptation from the song of that name eomposed in honor of Lord Rodney, the English admiral who won some signal victories over the Spanish and French fleets in 1780 and 1782 respectively.

The melody, no doubt much older, was also called “My Name is Moll Mackey” and “The Praises of Limerick.” Following is the air of “Rodney’s Glory” as sung by my father:

Similarly this once popular Long dance tune, of which there are several versions, was evolved from a slow song air, which the present writer often heard in boyhood days. From the drift of one line remembered - ”My hook began to glitter, and my flail it was in order” - it would appear that the song was of the narrative class, describing the adventures of one of those who migrate annually to engage in harvest work in more fertile fields.

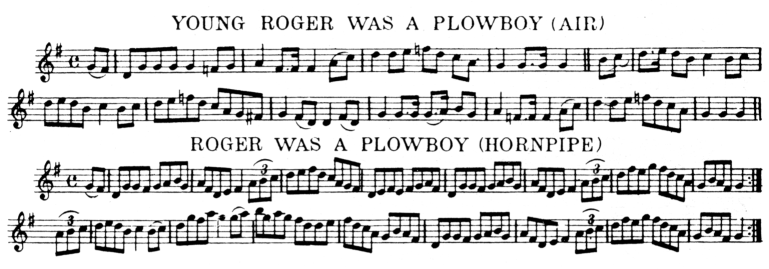

YOUNG ROGER WAS A PLOUGHBOY

This old air taken from Dr. Joyee’s Ancient Irish Music will serve to illustrate how readily a strain so simple may be converted into a typical Irish hornpipe.

THE CAMPBELLS ARE COMING, and MISS McLEOD'S REEL

No tunes have enjoyed greater popularity for many generations than the above named. “The Campbells are Coming” or “An Seanduine” as it is called in Ireland, was printed as early as 1750, and it is historically certain that “Miss MeLeod's Reel” was one of six tunes played by the Galway pipers in 1779, for the entertainment of Beranger, the French traveler. The antiquity of both tunes is therefore beyond question, and ordinarily one would not suspect their close relationship.

Any discriminating musician who will examine their structure and compare their similarity of strain cannot escape the conviction that both tunes had a common origin or that “Miss MeLeod's Reel” was derived from “The Campbells are Coming,” or its Irish equivalent “An Seanduine”

JIGS DERIVED FROM MARCHES

In stating that most if not all traditional Irish jig tunes were originally marches or song airs, we have the authority of the illustrious Dr. Petrie. Obviously Jackson’s compositions, published in his lifetime, are not of this class. Some have come down to us but little altered from their most ancient settings; while not a few others have been so disguised in the process of evolution as to almost lose their identity.

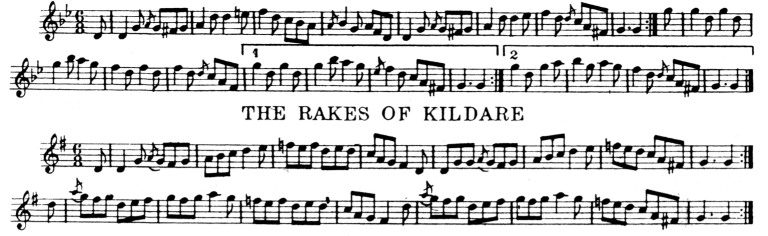

For instance, who would question the antiquity of a jig so generally known as “The Rakes of Kildare?” Yet when compared with “Get Up Early...”, an ancient march melody which Bunting obtained in 1802 from R. Stanton at Westport, county of Mayo, it is plainly evident that the march is the parent tune. “Very ancient author and date unknown,” is Bunting's notation on the latter.

GET UP EARLY

JIG AND REEL FROM SAME STRAINS

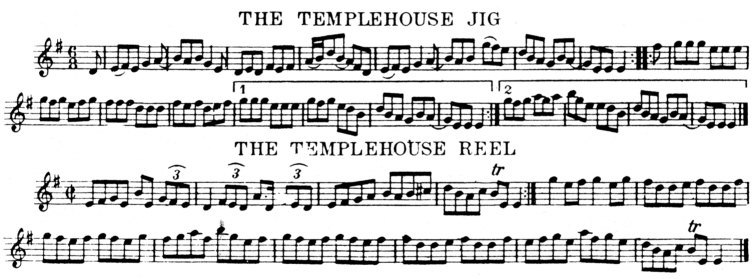

Instances of jigs and reels being evolved from the same strain, or of one being derived from the other, are more numerous than is generally supposed. Some pipers and fiddlers are surprisingly expert in that line of composition, or adaptation. A change of arrangement especially if in a different key, will oftentimes constitute an apparently new tune.

The most ordinary ear can discern the relationship existing between “The Templehouse Jig” and its offspring, “The Templehouse Reel,” each in its class is a tune of distinct merit, though identical in tonality.

JACKSON'S MORNING BRUSH

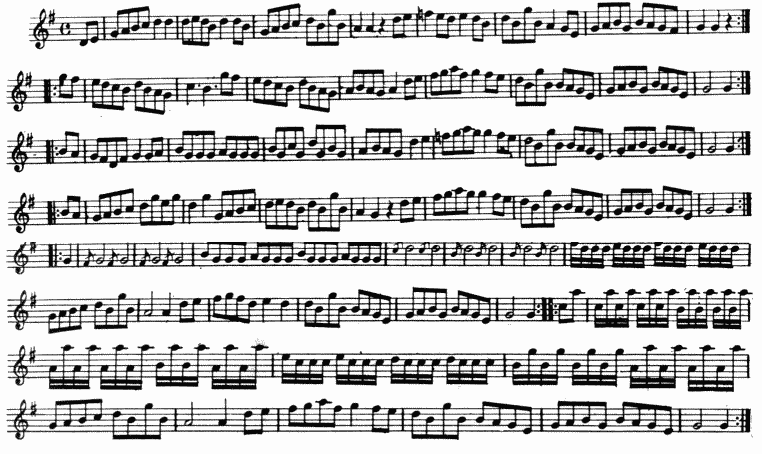

A good example of a jig which grew from two to four strains in much less than one generation is “Jackson’s Morning Brush,” the best known of “Piper” Jackson's compositions. Following is the version of it as played by Bernard Delaney and others of our best traditional musicians in Chicago.

The earliest setting of this favorite jig is probably that taken from a MSS. Collection of 1776 by Grattan Flood and published in his recent work, The Story of the Bagpipe. It consists of only the first and third strains of Delaney’s version. The setting which we find in volume one of Aird's Selection of Scotch, English, Irish, and Foreign Airs, published in 1782, comprises the first, second and third strains of our example without the second finish to the third.

Bunting’s setting of this tune obtained from a piper in 1797 was extended to four strains in the same order of sequence as ours, but besides lacking the second finish before mentioned there are a few minor differences not at all to its advantage.

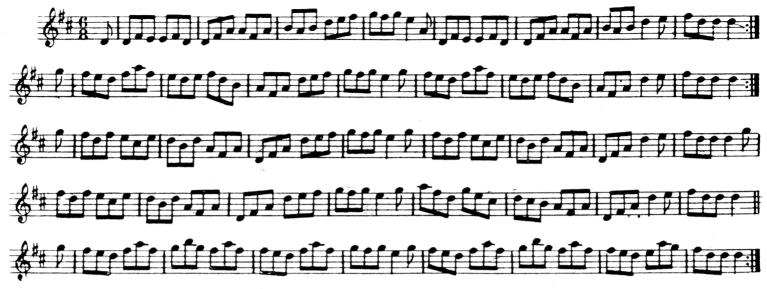

JACKSON'S MORNING BRUSH

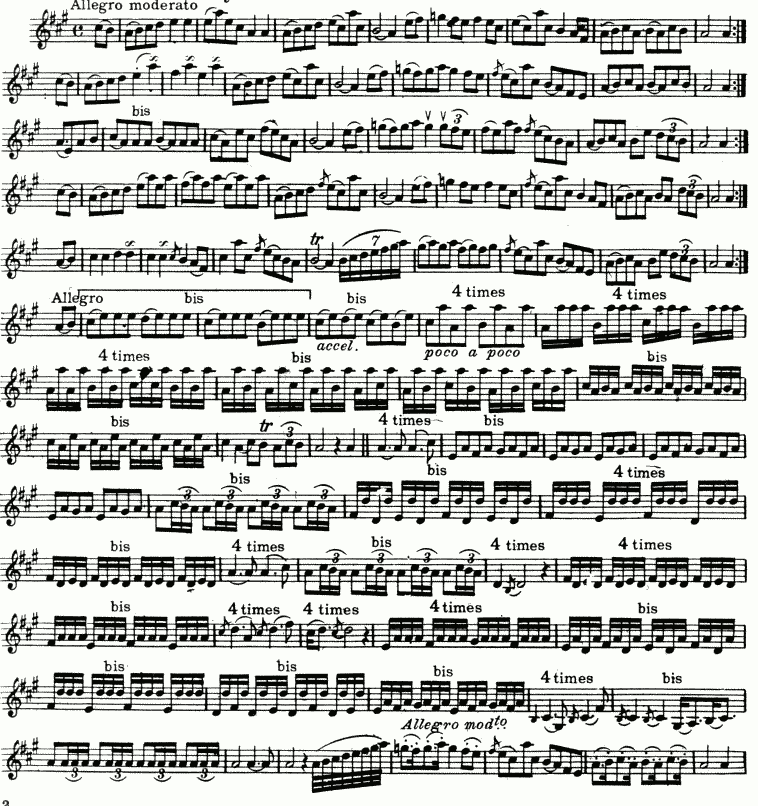

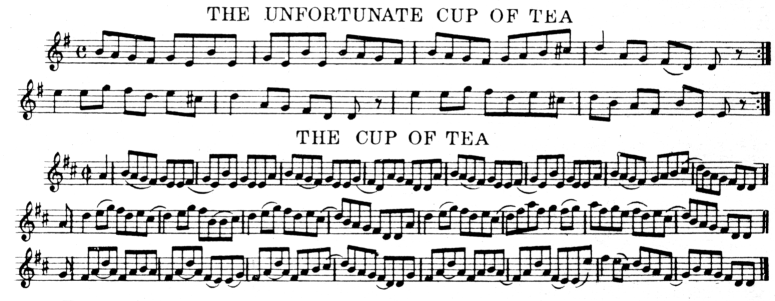

Whi1e engaged in this line of demonstration we may as well submit for consideration two settings of a popular reel which presents unmistakable evidence of having been the subject of somewhat similar development. The first setting as printed in Haverty’s Three Hundred Irish Airs is named “The Unfortunate Cup of Tea.”

The setting of this fine reel as printed in O’Neill’s Dance Music of Ireland, was the version noted down from the playing of James Kennedy, one of the famous fiddlers of the Irish Music Club of Chicago. Among the “craft” it was called “The Cup of Tea.”

TRADITIONAL MUSIC

Although convincing evidence has been presented, much more is available to support the claim that traditional Irish music has quite generally wandered from its originals, in all of its different varieties. Even that “Queen of Irish airs:” “The Coulin” has its “Old Coolin” and a still more primitive version in the Petrie colleetions, and such a slashing marching tune as “The Boyne Water” is represented by two apparently older versions - Nos. 1529 and 1530 - in the same repository of ancient Irish music, disguised under Irish names of different import.

A volume, much less a chapter, would scarcely do justice to this subject, but we trust examples enough have been submitted to furnish food for thought especially to those who in their self-complacent attitude of musical infallibility, will tolerate no standard of excellence or perfection but their own.