CHAPTER XIV

FAMOUS COLLECTORS OF IRISH MUSIC

I.OVE of music for its own sake is invariably the inspiring motive which prompts and sustains the musical antiquarian, or collector of Folk Music in every age, and in every country. Like the benefactors of their race who have devoted their lives and even their fortunes to the acquirement of rare manuseripts, historical documents, and other interesting things, collectors of folk lore, and Folk Music, are all enthusiasts in their chosen subjects.

Affected no doubt by the tragic vicissitudes of their country, the Irish did not begin the work of collecting the melodies of Erin until long after the English and Scotch had invaded the held, and incorporated many stray Irish tunes in their publications.

As early as 1594 a manuscript collection of music, including several Irish airs, was compiled by William Ballet, a Dublin actor. In musical bibliography it is known as William Ballet's Lute Book, and is preserved in Trinity College Library.

Although many musical works were printed in England in the first half of the seventeenth century it was not until 1650 that any great collection of music without words was undertaken. From that date and for seventy-five years there-after various editions more or less enlarged of The English Dancing Master, commonly called Playford's Dancing Master, continued to come from the press, among the contents being not a few Irish tunes.

The same English publisher, John Playford, compiled and published in 1700 the first collection of Scotch music consisting of but sixteen pages and of which there is known to exist but one copy.

Though the subject of Music Collections has been dealt with at some length in Chapters XII and XIII of Irish Folk Music- A Fascinating Hobby, the occasion seems opportune to present brief biographies of certain colleetors whose conspicuous labors in the line of original research can never be too highly appreciated. In fact theirs were the storehouses from which many minor colleetors and publishers freely helped themselves.

The first music publishers of any note in Dublin were John and William Neale, father and son, and it is recorded, they played an important part in matters musical in their day, even to the extent of managing most of the entertainments in the city. The elder Neale or O’Neill - as the surname was sometimes referred to, was in 1723 connected with a musical club which afterwards developed into a very important musical association.

Their meeting place was at a tavern at Christ’s Church Yard, and it is worthy of note that it was at this location the Neales published in 1726, (or 1720 according to Bunting) a little volume with the modest title: A Book of Irish Tunes. About the same time they brought out A Collection of Irish and Scotch Tunes; three books of English Airs, and a volume of Country Dances. Two thin folio volumes of songs and airs from the Beggars' Opera which abounded with Irish airs followed in 1729, but their special claim to distinction in this connection lies in the fact that they were the pioneer collectors and publishers of Irish music.

The Neales were also the builders of the Musick Hall in Fishamble street, opened in 1741, and in which Handel conducted his first public performance in Dublin.

John Neale died before this event, but the son, William, survived to an advanced age, the date of his death occurring in the year 1769. Musical taste and talent persisted in the family for Wi1liam’s son, Dr. John Neale, became the best amateur violinist of Dublin.

After the Neales, Neills, or O’Neills, as they were variously called, the next collector of prominence was Burk Thumoth, whose fame rests on his two celebrated collections, Twelve Scotch, and Twelve Irish Airs, with Variations, etc., and Twelve English, and Twelve Irish Airs, with variations, etc., published about the years 1742 and 1745 respectively. Both volumes are “Set for the German Flute, Violin or Harpsichord.”

No details of Thumoth's life are available except that he was an Irishman and a famous performer on the flute.

In his third volume Bunting refers to Burk Thumoth’s Collection of Irish Tunes as having been published about 1725. That this date is much too early is clearly set forth in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. On the title page of the first edition it is stated that they were printed for John Simpson, but it appears that Simpson did not engage in the publishing business until long after that date. Again James Oswald’s two collections of Curious Scots Tunes are advertised on the title page of Thumoth's first “Book.” Yet Oswaldys volumes were not printed before 1742.

Omitting the date of publication, formerly a eonimon practice, still prevails, but less frequently, hence the discrepancies which naturally arise.

A celebrated Irish piper, first name unknown, who flourished in the latter part of the eighteenth and first part of the nineteenth centuries, must be reckoned as one of the most famous collectors of Irish music, but being listed among the notables of his profession in Chapter XIX further reference to him in this connection is unnecessary.

The selection of Edward Bunting to reduce to musical notation the tunes played at the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792 inimortalized his name and gave his talents that trend which eventually led to such important results. To this circumstance, probably, he owes the preservation of his name from the oblivion which was the fate of most of his professional contemporaries.

Edward Bunting was born in the town of Armagh in 1773, his mother being the daughter of an Irish piper named Quinn, whose ancestor, Patrick Grauna O'Quinn, lost his life in the rising of 1641. His father was an English mining engineer from Derbyshire, who came to Ireland to open a coal mine in county Tyrone. The three Bunting brothers, Anthony, John and Edward, studied music at Armagh and became professional organists. Contrary to the general belief that the subject of this sketch had no previous acquaintance with traditional Irish music, it appears that young Edward mingled freely with his mother's kindred in his boyhood days, and confessed to a liking for the native music, which increased on more intimate acquaintance in later years.

So rapidly did he progress in his musical studies that he outclassed his teachers and the organists who employed him in a subordinate capacity. Teaching pupils much older than himself was not without its embarrassments, especially when they happened to resent his exercise of authority. Not only did he excel in music but in the mechanical skill to tune and repair the instruments.

Recognized as a prodigy, hero-worship came near spoiling him. Petted and painpered, he grew peevish and indolent, and like many another genius of brilliant prospects, Bunting may have disappointed the expectations of his early years, had not the event which laid the foundation of his fame occurred, when he was but a rosy-cheeked blue-eyed boy of nineteen.

For four years after the Belfast Harp Festival of 1792, Bunting tells us, he devoted himself to the work of collecting airs. Encouraged and hnanced by the patriotic Dr. MacDonnel1 and other liberal citizens of Belfast he travelled into Tyrone and Derry, visiting the centenarian Hempson at Magilligan after his return from Belfast, and spending a good part of the summer in the mountainous districts around Ballinascreen, where he obtained quite a number of admirable airs from the country people.

His principal acquisitions he claims to have collected in the province of Connacht where he was the guest of the celebrated Richard Kirwan, founder of the Royal Irish Academy. Having succeeded beyond his expectations he returned to Belfast, and in the year 1796 produced his first volume containing sixty-six native Irish airs never before published.

No sooner had this tangible result of Bunting’s painstaking labor come from the press than a Dublin pirate-publisher brought out a cheap edition, undersold Bunting’s half guinea volume, and robbed him of the fruits of his enterprise. And that was not all. When Tom Moore - at the suggestion of W. Power, his publisher, commenced his renowned Irish Melodies he found Bunting's volume of garnered airs ready at hand for his purpose.

From Moore’s own memoirs we learn that Robert Emmet was an eager listener, as he played over the airs from Bnnting’s collection at Trinity College. Wedded to Moore’s inimitable verses the airs gained in popularity, but the profits from this source went to the poet and his publisher and not to Bunting.

Writing of the latter’s work in 1847 Petrie says: It has now been long out of print and too generally forgotten, but the majority of its airs have been made familiar to the world by the genius of Moore, to whom it served as a treasury of melody, as may be gathered from the fact that of the sixteen beautiful airs in the first number of the Irish Melodies, no less than eleven were derived from that source. Even Lover did not disdain to seek inspiration in its pages for “The Angels' Whisper.”

Regardless of the fact that his efforts were unrewarded by due financial return, and that others had reaped both fame and fortune as a result of his labors, Bunting continued persistently in his work of research and accumulation as opportunity offered. To him it was a labor of love to be indulged in, during the intervals of his occupation as organist and teacher.

In 1809 he published his second volume: A General Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland, Arranged for the Pianoforte and Voice, and containing “An Historical and Critical Dissertation on the Harp.” The author had intended to have Irish songs set to the 77 airs in the work, but as Patriek Lynch, a capable Irish scholar whom he had engaged to assist him in this feature of the project became involved in the political Complications of the times, the plan was abandoned and English verses by Thomas Campbell, Miss Balfour and others were utilized instead.

This splendid work placed Bunting in the foremost rank of British musicians and at the head of those of his own country. Yet fame and worry was all he got out of it. Had it not been for the Iiberality of his Belfast subscribers its sale at one pound six shillings a volume would not have defrayed the expenses of publication. Failing to dispose of his elaborate work otherwise he ceded his interests to the publishers for a trihing sum.

A musical prodigy in childhood, though an orphan in early youth, his talents procured him adulation and an easy living. As his years advanced, his fame increased, his company was sought in the best society, and he formed the acquaint- ance of distinguished men of letters, as well as the most eminent in his own profession.

A confirmed diner-out, and enjoying life thus pleasantly and even luxuriously, Bunting remained unmarried until his forty-sixth year.

Many of his collected airs were as yet unpublished and it was hardly probable that he would venture to repeat his bitter experience, with a family now dependent on him for support had not the persuasion of friends and the goading of Dr. Petrie stirred his indolent spirit into renewed activity.

Although Moore, eager for additional airs suitable for his lyrics, pronounced the great collector's third volume, The Ancient Music of Ireland, published in 1840 “a mere mess of trash,” the genial Tom made amends soon after by acknowledging his indebtedness to Bunting for his acquaintance with the beauties of native Irish music, graciously admitting that it was from his early collections his “humble labors as a poet have since then derived their sole lustre and value.” This last and in many respects his greatest work contained in addition to its hundred and a half airs and musical examples, much valuable information relating to the characteristics of Irish melody, ancient musical terms, notices of remarkable airs and sketches of famous harpers. It also included “An Essay on the Harp and Bagpipe in Ireland, by Samuel Ferguson, Esq., M. R. I. A.,” and other interesting articles.

Highly appreciative notices of the work were printed in The Atlzenezmz and other influential periodicals. “We close with regret Mr. Bunting’s volume because we believe that with it we take leave of the genuine Music of Ireland,” wrote Robert Chambers in Chambers Edinburgh Journal. “It must not be regarded as a musical publication alone, but as a National work of the deepest antiquarian and historical interests.” Dr. Petrie proclaimed it, “A great and truly national work of which Ireland may feel truly proud. To its venerable editor Ireland owes a deep feeling of gratitude, as the zealous and enthusiastic collector and preserver of her music in all its characteristic beauty, for though our national poet Moore, has contributed by the peculiar charm of his verses, to extend the fame of our rnnsie over the civilized world, it should never be forgotten that it is to Bunting the merit is due of having originally rescued our national music from obscurity.”

Bunting did not long survive his final triumph, but his last years were soothed by the consolation that his life-work was duly appreciated. He died suddenly while preparing to retire on the evening of December 21, 1843, at the scriptural age of three score and ten.

Farquhar Graham states in the Introduction to Surenne's Songs of Ireland that Bunting “died at Belfast and was interred in the cemetery of Mount Jerome.” Hence our error in Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby.

The great collector died in Dublin, to which he removed in 1819 at the time of his marriage. Our esteemed friend, Prof. P. J. Griffith of the Leinster School of Music who reminded us of our error, obligingly sent us a drawing of the granite monument in the Dublin General Cemetery, Mount Jerome, on which the following is inscribed:

Sacred

to the memory of

Edward Bunting,

who died 21st December, 1843,

aged 70;

Mary Anne Bunting,

his Wife,

who died 27th May, 1863,

and their only son,

Anthony Bunting,

who died 10th July, 1849,

aged 29.

Of the host of Irish musicians whose talents have imniortalized their names during the last century, the subject of this brief biography is one of the few who paid more than casual attention to the native dance music.

R. M. Levey, whose true name was Richard Michael O’Shaughnessy. Was born at Dnblin in ISII ‘and died there in 1899. Displaying a decided predilection for music in boyhood days, he served an apprenticeship to James Barton from 1821 to 1826, after which he entered the Theater Royal Orchestra, being then but fifteen years old. A few years later he became musical director.

As a violinist of unusual gifts he was well known at the Crystal Palace Handel Festivals, and other musical events in London, and the incident which led to his change of name occurred on the occasion of his first visit to the metropolis. When asked, his name by the official in charge of enrollment, he promptly replied “Richard Michael O’Shaughnessy.” “O'whatnessy ?,” echoed the astonished official. “O'Shaughnessy,” repeated the bewildered violinist. “My friend,” volunteered his questioner, “you can never hope to make a success in professional life with an unpronouncable name like that. By the way what was your mother's maiden name ?” When told it was Leavy, the official wrote down Levey, and announced to the abashed musician, “Hereafter you will be known as R. M. Levey in this establishment.,’ And true enough it is by that Hebraic cognomen he is known in musical history.

Wallace and Balfe were among his most intimate friends and he toured Ireland in 1830 with the latter's opera company. In all, Levey composed nfty overtures and arranged the music for forty-four pantomimes, and he often alluded with pardonable pride to Sir Robert Stewart, and Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, as his pupils. He was also professor of the violin at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, of which he was one of the founders.

His oldest son and namesake, born in 1833, became a violinist of renown and won distinction at concerts in Paris and later in London where he was known as “Paganini Redivivus” Another son, William Charles Levey, no less talented, also won recognition in Paris, and was subsequently conductor at Drury Lane and Covent Garden theaters.

With all his accumulated honors this famous Irish musician did not disdain the simple folk music of his ancestors. On the contrary all through life he cherished a love for the unpretentious melodies of the Green Isle, which he noted down from the playing of traditional fiddlers and fluters in Dublin and London.

In the latter city he published in 1858, and 1873, two unclassified collections of The Dance Music of Ireland each containing one hundred tunes. Only in one instance, he tells us in a footnote, did he alter in the slightest degree the tunes which he obtained as above stated. Levey’s was the first work ever printed devoted to Irish dance music exclusively.

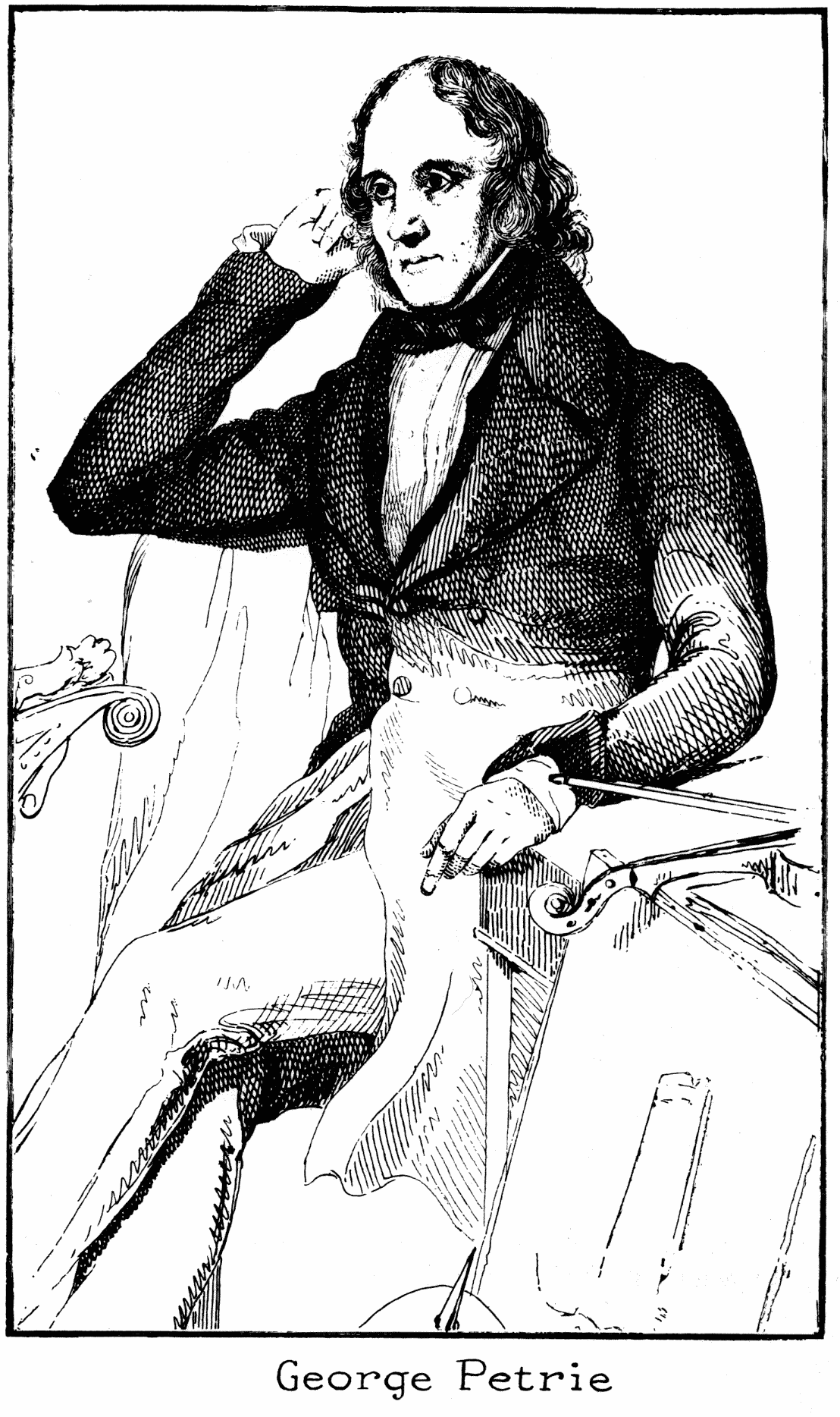

One of the most learned and versatile of the distinguished sons of Erin was the amiable George Petrie - artist, archaeologist, journalist and musician. Born at Dublin in 1789, he was the son of James Petrie, also a native of the Irish capital but of Scotch ancestry. When ten years old George entered the school of Mr. White at which Sheridan, Moore, and several others of his famous countrymen were educated. In due time he studied art under his father who was a talented portrait painter, among the subjects of his brush being Lord Edward Fitzgerald, Philpot Curran and Robert Emmet. The son soon became noted for his skill in water colors, and was in much demand in illustrating works on travel and topography, because his drawings were peculiarly imbued with truthfulness and possessed that indescribable charm which has been styled feeling. It was while engaged in this congenial pursuit that he acquired the vast fund of antiquarian information which enabled him to accomplish more in the interest of Irish archaeology than had been done by a single individual before or since.

He became librarian of the Royal Irish Academy in 1830, was associate editor of the Dublin Penny Journal in 1832, founded the Irish Penny Journal in 1840, and was the projector of the museum of said academy for which he collected over 400 ancient Mss., among them being the original manuscript Annals of the Four Masters.

From 1833 to 1846 Petrie was actively engaged in the Ordnance Survey of Ireland, had charge of its historical and antiquarian department, and numbered among his staff Prof. Eugene O’Curry and Dr. John O’Donovan, the translator of the Annals before mentioned.

The most notable of Petrie’s numerous antiquarian writings was The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland, Anterior to the Anglo-Norman Invasion, Comprising an Essay on the Origin and Uses of the Round Towers of Ireland. The Essay on the Round Towers, originally written in 1833, won the gold medal and prize of fifty pounds offered by the Royal Irish Academy for the best essay on the subject.

Not less noteworthy were Dr. Petrie’s patriotic services in another field of endeavor. From his seventeenth to his seventieth year he was an assiduous collector of Irish Folk Music. During his sketching raids his mind was not altogether absorbed by the beauties and romance of the seenes through which he passed. He possessed a perfect ear and was proficient on more than one instrument. Wherever he went through the country and heard an ancient Irish tune that was new to him he carefully noted it down, even sometimes on a sketch book page. In this manner was formed his singularly interesting and invaluable collection of ancient lrish airs, the great majority of which but for his instinctive care would have been buried in oblivion; the old inhabitants of the districts where he found them in use, being long since dead, and the younger generations having emigrated or dispersed. The first step in each locality visited was to make inquiry concerning people who could sing or play music, or even whistle tunes. So gentle and unassuming was Dr. Petrie and so charming his personality that he found no difficulty in gaining the confidence of the people who met him by appointment in some commodious kitchen generally, when he noted down such tunes as caught his fancy.

Not a few of his melodic treasures were obtained from ballad singers. Invariably gifted with fine voices they attracted crowds at every fair and market in those days, and contributed more than any other influence to keep alive and in circulation the simple melodies of the peasantry.

Manuscript collections of music that otherwise might have never gained the light of publicity proved a prolific source of pleasure and profit to Petrie. Such as those compiled by Mr. Patrick O’Neill of Kilkenny in 1785, and the amiable sagart, Father M. Walsh, P. P. At Iveragh, County Kerry, who, is is said, was the original of A. P. Graves, “Father O’Flynn.”

How or when the subject of this sketch learned to play the fiddle and the flageolet, or by whom taught does not appear to be a matter of record, but we know that he was proficient on both, and that he rendered the native music enchantingly on the former instrument, but played only to a sympathetic audience. Furthermore he had little patience with the affectation of the would-be “quality” of the provinces who favored quadrilles and gallopes instead of the native dances. “But what a monstrosity - to dance quadrilles in Galway!” he exclaims. “Dance indeed, no but a drowsy walk and a look as if they were going to their grand-mothers’ funerals. Fair Galwegians -- for assuredly you are fair - put aside the sickly affectation of refinement which is equally inconsistent with your natural excitability and with the healthy atmospheric influences by which you are surrounded. Be yourselves, and let your limbs play freely and your spirits rise into joyousness to the animating strains of the Irish jig, the reel, and the country dance; so it was with your fathers and so it should be with you.”

From his own pen of later years we learn that he was a passionate lover of music from childhood and of melody especially, “that divine essence without which music is but as a soulless body,” and that the indulgence of this passion had been indeed one of the great it not the greatest source of happiness in his life. Though he had been at all times a devoted lover of music and more particularly of the melodies of his country, which he considered to be the most beautiful national melodies in the world, neither the study nor practice of music, had been anything more than the occasional indulgence of a pleasure during hours of relaxation from the fatigues of other studies, or the general business of life. Neither had he contemplated giving even a portion of his collection publicity in his own name.

With characteristic liberality and unselfishness, Petrie contributed a number of airs to the poet Moore which for the nrst time appeared in his Irish Melodies, and shortly afterwards he enriched Francis Holden. Mus. Doc., with a much larger number which were first printed in his father's, Smollett Holden’s Collection of Old Established Irish slow and quick Tunes published in 1800.

Petrie’s acquaintance with Bunting began shortly after the publication of the latter’s second volume in 1809. Interested only in the preservation of the melodies which he had accumulated, Petrie generously offered him the use of the whole collection or such portions of it as Bunting may select, provided that due acknowledgement be made of the source from which they had been obtained.

After the acceptance of over two dozen airs, of which he printed only seventeen, Bunting could not be persuaded to accept even one more lest the public might say that the greater and better portion of his third volume published in 1840 was derived from Petrie.

Enthusiast as he was, the latter kept on adding to his store year by year, cherishing the hope that some fortunate circumstances might intervene and lead to the publication of his rnelodic treasures eventually. And he had not hoped in vain, either, for the formation of the Society for the Preservation and Publication of the Melodies of Ireland, in December, 1851, presented the desired opportunity.

George Petrie, then sixty-two years old, was elected president. Nine of the ten vice-presidents were noblemen, and all members of the council - twenty-three in number - were men of learning and distinction.

Encouraged and sustained by this notable galaxy, Petrie set to work, and published in 1855 a handsome tolio volume (containing 147 assorted numbers) entitled The Petrie Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland, Arranged for the Pianoforte, edited by Georgc Petrie, LL. D., R. H. A., V. P. R. I. A., Vol. I. Several other impressive honors and announcements on the title page are omitted, but enough has been stated to show that the movement did not fail for lack of patrons of prominence, and although the airs and dance tunes were “illustrated by a great quantity of criticism and observation” which was of absorbing interest, yet fail it did, owing to the same cause that paralyzed so many similar attempts at popularizing Irish music -- public apathy and indifference.

The editor’s misgiving as to the success of his work on account of the decline of the “racy feeling of nationality and cultivation of mind so honorable to the Scottish character’, was justified by the result. Though his treasury of melodies would fill many volumes, only one, containing less than one-tenth of them, was published, and the undertaking so full of promise at its inception was abandoned.

Although checked in his cherished aims, his ardor in adding to his collection suitered no diminution. During a visit to the Arran Islands in 1857, with a party of friends, they made their headquarters at a cottage near Kilronan. The same course was pursued as on other like occasions, and when the persons “who had music” were assembled, night after night, the work of taking down the names and words in Irish was assigned to Prof. Eugene O'Curry, while Dr. Petrie, equipped with fiddle and writing material, scored the music bar by bar as it was sung to him by each vocalist, who in rotation “took the chair,” or rather the stool, in the chimney corner. When the “proofs” had been corrected Dr. Petrie would play the airs or tunes over and over again, to the astonishment and delight of his audience. Respected and lamented universally, the amiable enthusiast died in 1866, leaving four daughters but no son.

A small supplement to The Petrie Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland, containing thirty-six airs, saw the light of day in 1882 - sixteen years after his death - but it was not until the Irish Literary Society of London engaged Sir Charles Villiers Stanford to hunt up his almost forgotten manuscripts and take charge of their publication, in 1902 and 1905, that Dr. Petrie’s dream was ultimately realized.

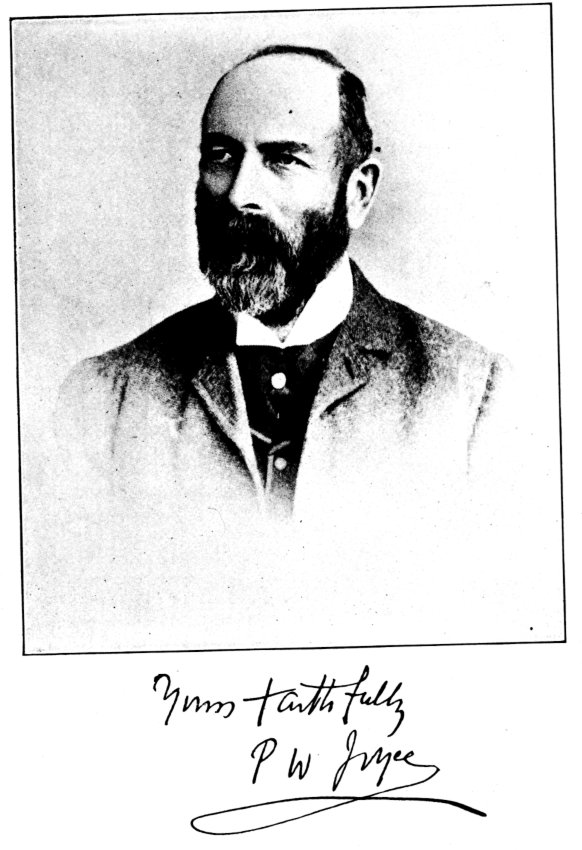

Few men have been so favored with fame and fortune in their lifetime as the genius whose name heads this sketch. Gifted with literary as well as musical talent, Dr. D. W. Joyce is the author of several works of antiquarian value, notably Irish Names of Places, published in 1869.

Born in 1827 at Ballyorgan, among the Ballyhoura Hills, which divide south-eastern Limerick from the County of Cork, he was nurtured in an atmosphere of tradition, and, loving music, instinctively, like his prototype, Petrie, he learned to play the fiddle, and mingled with the peasantry in their pastimes and entertainments.

In the Preface to his Ancient Irish Music he says: “I spent all my early life in a part of the country where music and dancing were favorite aniusements; and as I loved the graceful music of the people from my childhood, their songs, dance tunes, keens and lullabies remained on my memory almost without any effort of my own. I had, indeed, excellent opportunities, for my father’s memory was richly stored with popular airs and songs, and I believe he never sang or played a tune that I did not learn. Afterwards, when I came to reside in Dublin and became acquainted with the various published collections of Irish music, I was surprised to find that a great number of my tunes were unpublished, and quite unknown outside the district or province in which they had been learned. This discovery stimulated me to write down all the airs I could recollect, and when my own memory was exhausted, I went among the peasantry during vacations for several successive years, noting down whatever I thought worthy of preserving, both music and words.”

Shortly after Mr. Joyce went to reside in Dublin, in the early bloom of manhood, a copy of the prospectus of the Society for the Preservation and Publication of the Melodies of Ireland fell into his hands. Becoming interested in the project, he ventured to call on Dr. Petrie. The president of the organization. The timidity, which at first almost nnnerved the young man, soon vanished on finding that the learned antiquary was a charming, kindly and unpretentious old gentleman whose gentle voice and manners soon made him feel quite at ease. Dr. Petrie was evidently surprised at the extent of his caller’s repertory of strange tunes, and, finding that the young musical enthusiast could write music, he requested him to jot down a few dozen of his best.

“With a little book filled with airs, all from memory, I returned at the end of a week.” Dr. Joyce writes: “The good doctor looked at the MS. and fell upon it much as a gold miner might fall upon a great and unexpected nugget. And so commenced my collection of Irish airs, at first entirely from memory, all of which I handed over to Dr. Petrie, hook after book, according as each was filled. And this continued for Several years.”

Dr. Petrie acknowledges his indebtedness to “Mr. Joyce” all through his collections, but as the death of the venerable collector in 1866 put an end to any lingering hope that he would bring out a second volume of The Petrie Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland, Dr. Joyce wisely undertook to publish his collection himself.

Accordingly, in 1873 there came from the press Ancient Irish Music; Comprising One Hundred Irish Airs Hitherto Unpublished, Many of the Old Popular Songs, and Several New Songs: Collected and Edited by P. W. Joyce, LL. D., M. R. I. A. The descriptive text accompanying each number is by no means the least interesting part of the volume. This was followed in 1888 by Irish Music and Song: A Collection of Songs in the Irish Language, Set to Music.

A far more pretentious work than either is Old lrish Folk Music and Songs: A Collection of 842 Irish Airs and Songs Hitherto Unpublished - Edited with Annotations for The Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, by P. W. Joyce, LL. D., M. R. I. A., President of this Society.

This very interesting work is made up of three separate collections, the largest and best, consisting of 429 numbers, being from Dr. Joyce himself. The Forde MSS., compiled in the second quarter of the nineteenth century by William Forde, a distinguished Cork musician who edited the Encyclopedia of Melody, published before 1850 in London, yielded 256 more; while the Pigot MS. Collection, assembled by John Edward Pigot, of Dublin, M. R. I. A. and honorary secretary to the “Society for the Preservation and Publication of the Melodies of Ireland,” contained 157 selections.

Still hale and hearty in his eighty-sixth year, and devoted to the enjoyment of his cherished hobby, Dr. Joyce is likely to be heard from again in the world of music before be becomes a nonogenarian or joins the “heavenly choir.’.