JEREMIAH MURPHY

[from 'Irish Minstrels and Musicians', Capt. Francis O'Neill, Chicago, Regan Printing House, 1913.]

CHAPTER XIX

FAMOUS PERFORMERS ON THE IRISH OR UNION PIPES IN THE EIGHTEENTH AND EARLY PART OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURIES

THE classification of Irish pipers not included in the two preceding chapters, with a view to draw lines of distinction for the convenience of readers, is by no means as simple as it seems.

The idea of listing them as “amateurs” and “professionals” was abandoned for the reason that an amateur in modern days has come to be regarded as a beginner rather than a non-professional.

Drawing the line at the century was no less objectionable. Some pipers had flourished in one generation and died young. Others, again, blest with longevity, lived and flourished in two centuries, and in one ease at least even in three. The divisions adopted, though somewhat indefinite, will, we trust, be found not objectionable.

In the state of society which prevailed in Ireland in the eighteenth century we can well imagine how exclusive were the "Gentlemen Pipers', as far as the public was concerned. It appears, however, from an incident mentioned by John O'Keefe, the celebrated dramatist and comedian, in his Recollections, published in 1826, that there was another class of "Gentlemen Pipers" intermediate between the titled and the plebeian, as the following stories of the times about 1770

will show:

SPIRIT of AN IRISH PIPER

“MacDonnell, the famous Irish piper, lived in great style – servants, grooms, hunters, etc. His pipes were small and of ivory, tipped with silver and gold. You scarcely saw his fingers move, and all his attitudes while playing were steady and quiet, and his face composed. One day that I and a very large party dined with Mr. Thomas Grant at Cork, MacDonnell was sent for to play for the company during dinner. A table and chair were placed for him on the landing outside the room, a bottle of claret and glass on the table, and a servant waiting behind the chair designed for him: the door left wide open. He made his appearance, took a rapid survey of the preparation for him, filled his glass, stepped to the dining-room door, looked full into the room, and said: `Mr. Grant, your health and company!’ drank it off, threw half a crown on his table, saying to the servant, `There, my lad, is two shillings for my bottle of wine, and keep the sixpence for yourself.’

“He ran out of the house, mounted his hunter, and galloped off, followed by his groom.

“I prevailed on MacDonnell to play one night on the stage at Cork, and had it announced in the bills that Mr. MacDonnell would play some of O’Carolan’s fine airs upon the Irish Organ. The curtain went up and discovered him sitting alone in his own dress; he played and charmed everybody.”

MacDonnell possessed several exquisite sets of pipes. One of them, made by the elder Kenna and dated 1770, Grattan Flood tells us, passed into the MacDonnell family of County Mayo and is now in the Dublin Museum on loan from Lord Macdonnell, late Under-Secretary for Ireland.

It is a most elaborate instrument, and if the date is correct it proves con- clusively that the Uilleann or Union pipes had been developed into a keyed instrument with regulators much earlier than generally supposed, and certainly long before Talbot was born.

None but those of moral fibre and strong power of resistance may hope to withstand the demoralizing influence of conviviality in at atmosphere of adulation which conspicuous talent invites. James Spence, who was famous as a piper in his teens, was not one of those, for the sands of his life ran out at the early age of twenty-eight.

This brilliant performer on the Union pipes was born near Mallow, in the County of Cork, about the middle of the eighteenth century. Little or nothing is known of his early years except that his fame was widespread throughout Munster.

Emulating the example of so many others of his profession, he visited Dublin and at once won favor with the students and faculty of Trinity College, but lost discretion, health and life in short order, as before stated.

Who flourished in the latter part of the eighteenth and the early years of the nineteenth century, was a piper of renown in his day. Like most of his class, he traveled extensively in Scotland and England. At the performance of the pantomime of Oscar and Malvina at Covent Garden Theatre in 1791 it is recorded that Courtney played the Union pipes with much effect, and in 1798, according to Manson, author of The Highland Bagpipe, he “played a solo on the Union pipes in the quick movement of the overture, with good effect, in a performance founded on Ossian’s poems.”

A writer in the Freeman's Journal, March 2I, 1811, commenting on the capabilities of the Irish bagpipe, says “the celebrated Courtney has fully established the captivating sweetness of the notes in alt.” We learn from Grattan Flood that he spent many years in England and was not only a good performer but a good teacher. More than that, he was a composer of many popular dance tunes not easily identitied at this late day. He died in London, but the date, 1794, conflicts with the account in Manson’s work, above quoted.

Meagre indeed was the information available concerning the life of this noted piper, until we came across an article on the evolution of the Irish bagpipe, published in an issue of the Freeman’s Journal of 1811, the year of his death.

Speaking of Crampton, the writer says: “Possessing musical taste and judgment far above any other performer on the Irish bagpipe, he managed the bass or drone tubes with such skill as to form a very pleasing accompaniment, and plainly showed what might be effected were that attention paid which is devoted to other instruments. Besides, he gave a softness to the general tone that was peculiarly pleasing, and his style was so chaste, so completely divested of anything piperly, that no doubt can now remain of the bagpipe being capable of as much feeling and expression as the organ or harpsichord.” In the Story of the Bagpipe the author names Crampton as one of the three most famous Irish pipers at the birth of the nineteenth century. Though a brilliant instrumentalist, he was not endowed with the gift of composition.

In a notice printed in the Freeman’s Journal of April 13, 1812, describing the attractions of Dignam’s tavern, at No. 14 Trinity Street, Dublin, we are informed that the proprietor has engaged the “celebrated Munster piper, Mr. Talbot, a pupil of the late Cramp, to play every evening after eight o’clock, Sundays excepted.” But who was Cramp? None other than Crampton, whose name had been abbreviated eolloquially into Cramp, and even corrupted into Crump. By the latter name he was immortalized by Dr. Petrie.

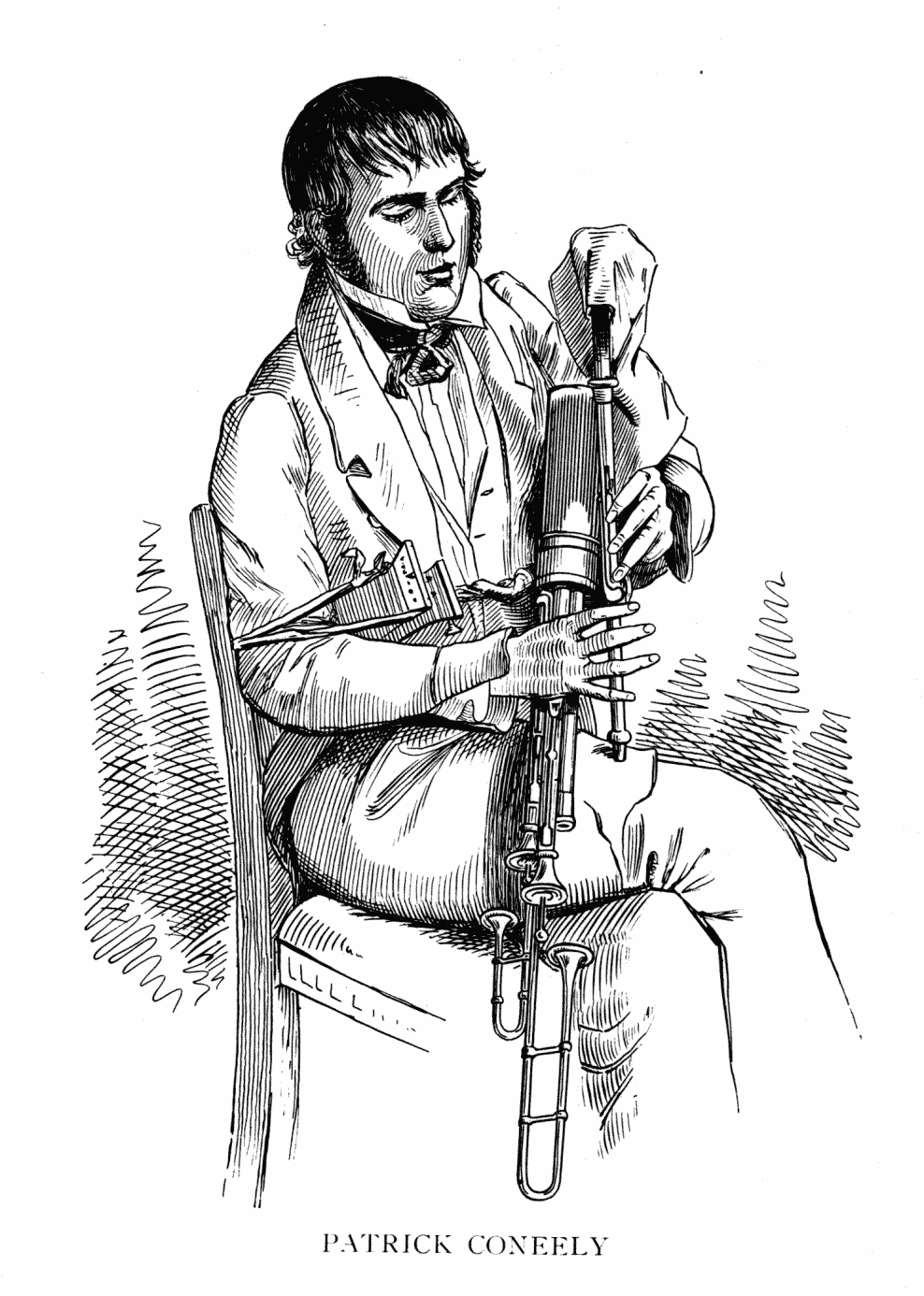

It was in writing a sketch of “Paddy” Coneely, the Galway piper, in 1840, that the amiable and gifted Petrie refers to Crump, whose instrument Coneely then possessed.

“As to the bagpipes,” in Petrie’s words, “they are of the most approved Irish kind, beautifully finished, and the very instrument made for Crump, the greatest of all the Munster pipers, or we might say Irish pipers of modern times, and from which he drew singularly delicious music. Musical reader! Do not laugh at the epithet we have applied to the sounds of the bagpipe. The music of Crump, whom we have often heard from himself on these very pipes, was truly delicious, even to the most rehned musical ear. He was a Paganini in his way – a man never to he rivaled. And who produced effects on his instrument previously nnthought of and which could not he expected.” Those pipes after Crump’s (or Crampton’s) death were saved as a national relic by the worthy and patriotic historian of Galway, James Hardiman, who in his characteristic spirit of generosity and kindness presented them to “Paddy” Coneely, as a person likely to take good care of them and not incompetent to do them justice.

Should an adequate work on Irish musical biography ever be undertaken, it is sincerely to be hoped the Union Pipers – true national minstrels – no less than the harpers will receive due consideration.

In vain we scan the pages of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians and British Musical Biography for the names of such renowned Irish musicians and composers as “Piper” Jackson, “Parson” Sterling, or even O’Farrell, an Irish piper and publisher of no inconsiderable fame in London for at least a score of years at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century.

Quite likely English writers and publishers had no conception of Irish music as performed on the improved Irish bagpipe, regarding both instrument and music as being no better than the rude performances of the pipers and street fakers of England as pictured by Hogarth and other English artists. Irish pipers were no rarity on the London stage since the last decade of the eighteenth century, and it is a matter of history that some of them, brilliant performers, were commanded to present themselves for the entertainment of royalty. With such recognition and patronage. It “passeth understanding” how the most prominent of them, and particularly one who published three notable eollections of music between the years 1797 and 1810, could be utterly ignored in such standard work as those named.

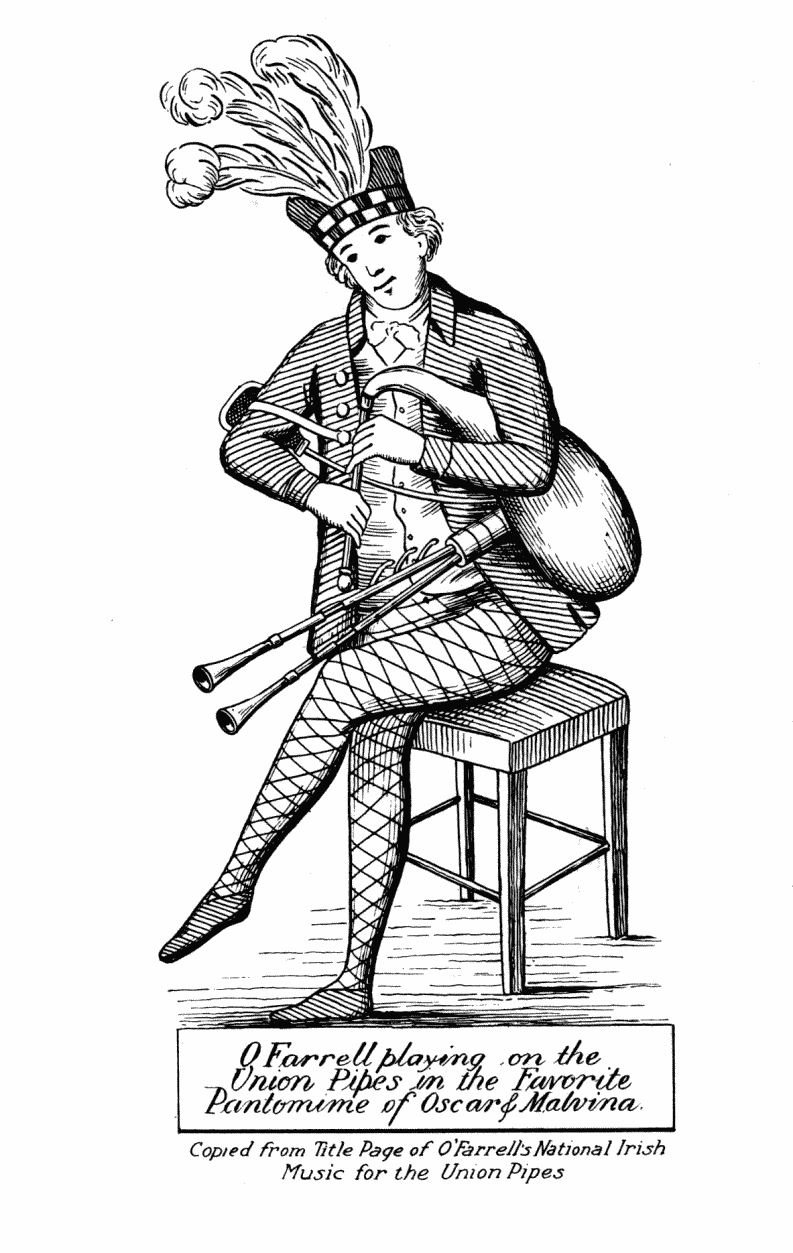

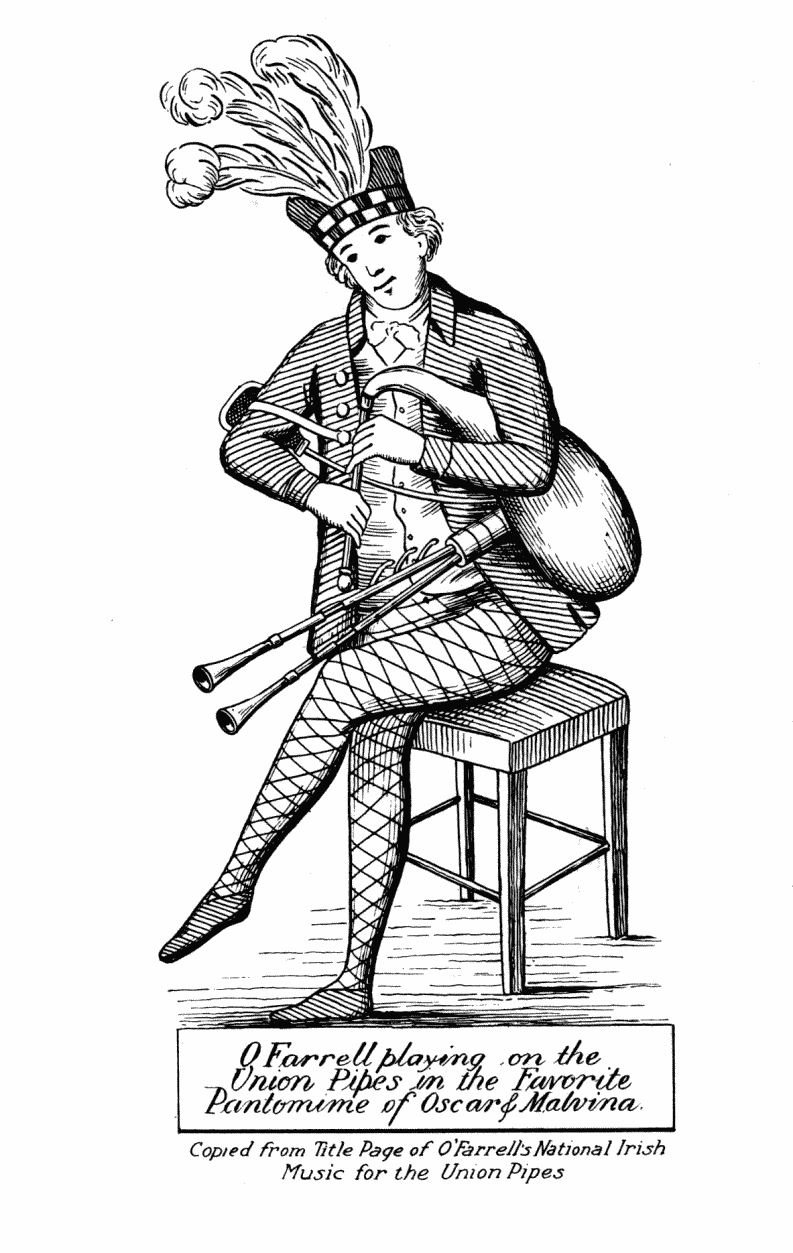

To the researches of the indefatigable Grattan Flood we are indebted for much of what little information we possess concerning this talented and enter- prising piper. Of his early life we know nothing. His introduction to fame dates from the year 1791, when he played the Union pipes in the pantomime of Oscar and Malvina at London. A man of affairs, evidently, he was practical and far- seeing, for after years of preparation, no doubt, he published a work entitled O’Farrell’s Collection of National Irish Music for the Union Pipes; Comprising a variety of the Most Favorite Slow and Sprightly Tunes Set in Proper Stile and Taste, etc., etc.; also a Treatise with the most perfect Instructions ever yet published for the Pipes.

Although music and a tutor for the Highland pipes had been published by Rev. Patrick MacDonald in 1784, O’Farrell’s Treatise was the first ever printed for the improved Irish instrument; and, by the way, the present writer procured through the courtesy of Grattan Flood a transcript of said Treatise from the copy of O’Farrell’s Work in the National Library at Dublin – the only one in Ireland, it is said – and inserted it as “Appendix A,’ in Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby. Since the publication of the latter work, in 1910, we have ascertained that O’Farrell,s collections repose in the National Library and not in the Trinity College Library, as therein stated.

Again in 1804 there came from the press O’Farrell’s Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, etc., etc., two small volumes of music, chiefly Irish, suitable for the instrument. These were followed in 1810 by two others similarly named.

This remarkable man, who must have been an excellent performer on the Union pipes, preserved, through his thoughtfulness and energy, many fine airs and dance tunes that but for his efforts would have been lost. His volumes are frequently quoted by Alfred Moffatt in tracing the history of many of the airs in his Minstrelsy of Ireland.

One of his own composition, called “O’Farrell’s Welcome to Limerick,” would seern to indicate that he had traveled in Ireland and that probably Limerick had been the place of his nativity.

That the unexpected sometimes happens was curiously illustrated in the experience of the writer recently. One of a dozen rare musical works sought through the medium of a London book agency whose specialty is tilling such orders, turned up with some rubbish. To my delight, it proved to be a perfect though discolored copy of O’Farrell’s first volume, of which there was but one copy in all Ireland! At last here was O’Farrell’s likeness in a vignette on the centre of the title page, garbed as he appeared on the London stage, and from it the etching on the opposite page has been reproduced. The set of Union pipes on which he played are quite distinct and unlike any other instrument we have ever seen. But possibly the artist was to blame and neglected to include the small drone and tenor with which such instruments are equipped.

Another noted performer on the Union pipes of the same period was Jererniah Murphy, a Galway man from Loughrea. In an issue of the Freeman’s Journal of Dublin, in September, 1811, Murphy’s arrival in the city is announced as follows:

THE IRISH PIPES

Jeremiah Murphy, late of Loughrea, begs leave to acquaint the

lovers of national music that he at present plays at Darcy's Tavern,

Cook Street, where he humbly hopes his exertions to please will

obtain for him that encouragement with which he has for so many

years been honored by the gentlemen of Munster and Connacht.

Early in 1813, Murphy transferred his services to the Griffin Tavern, on Dame Street – a sort of “Free-and-Easy” establishment. After 1815 he gave up entertaining the public in taverns, and his subsequent career is not a matter of record.

Available information concerning the subject of this sketch is decidedly meagre. Among the contents of Petrie’s Complete Collection of Irish Music are two unnamed jigs contributed by Dr. P. W. Joyce, “as played by James Sheedy.” One of them is an old Munster single jig set by Dr. Joyce in 1852 from the whistling of Michael Dineen, a farmer at Coolfree, parish of Ardpatrick, in County Limeriek. The latter had learned it in his youth “from the playing of James Sheedy, a celebrated Munster piper, who died a very old man, more than thirty years ago.”

As the above quotation was penned by Dr. Petrie in 1855, Sheedy must have been in his prime in the last quarter of the eighteenth century.

In a country so renowned as Ireland for the beauty of its melodies and the excellence of its musicians for so many long centuries, it was by no means surprising that famous performers on the harp and Union pipes abounded throughout the Green Isle until comparatively recent times.

One cannot help remarking that wherever mentioned in literature, almost all Irish pipers were alluded to in their respective circuits as “the greatest piper in Ireland.’,

A few, in the more modest estimate of their friends, were declared to be “the best piper in the county and the next one to it as well.” Who does not crave fame. The goal of universal aspiration? If exceptions exist, seek not for them among musicians. Following closely upon the heels of fame came rivalry and unhappiness. For no sooner was a piper’s reputation established than peace fled and anxiety commenced. Challenges from rivals eager to strip him of his title are anything but conducive to tranquility of mind, and, being blind – most of them – they never could tell when a disguised competitor was among their audience, picking up their best tunes and gaining information which might be an advantage and guide for future contingencies.

On a fact so generally known, it is scarcely necessary to quote Carleton, the celebrated Irish novelist, as an authority in saying that Union pipers were most numerous in the provinces of Connacht and Munster and fewest in Ulster, his native province.

It is much to be regretted that but comparatively few have escaped the oblivion to which the many have been thoughtlessly consigned. No one was more capable of the task of immortalizing the great pipers who we have no doubt came within the scope of his observation than Carleton. Yet only two have been so favored, namely, Talbot and Gaynor, though two others are briefly mentioned.

Born near Roscrea, in northeast Tipperary, in 1780, this celebrated musician and mechanic lost his eyesight when but fifteen years of age, as a result of an attack of smallpox. It is indeed a melancholy alternative that destines the poor sightless lad to an employment that is ultimately productive of so much happiness to himself and others. So the blind boy devoted his attention to music, and soon acquired such efficiency on the Union pipes that in a few years he was locally famous and in request for all festive gatherings at the seaside near the city of Waterford, where his family had settled after his misfortune. Having traveled about by land and sea for some years, he became a professional piper in 1802, when twenty-two years of age.

Though totally blind, Talbot possessed constructive genius of a high order, and was surprisingly delicate and exact in manipulation, not merely as a musician, but as a mechanic as well. His performance, singularly powerful and beautiful, charmed his audience wherever he went.

It is said that he opened a tavern in Little Mary Street, Dublin, yet it is certain he played in others. His playing of the Union pipes at a performance of Oscar and Malvina at Crow Street Theatre in 1816, Grattan Flood says. Upheld his reputation as a master of the instrument. He used to play in Lady’s Tavern, in Capel Street, where he arrived every night about eight o’clock and remained until midnight, or even later, occasionally. He was very sociable and, when drawn out, displayed much genuine Irish humor and rich conversational powers. Sometimes at a late period of the night he was prevailed upon to attach himself to a particular party of pleasant fellows who remained after the house was closed, to enjoy themselves at full swing. Then it was that Talbot shone, not merely as a companion, but as a performer. The change in his style and manner of playing was extraordinary; the spirit, the power, the humor and the pathos which he infused into his execution were observed by everyone; and when asked to account for so remarkable a change, his reply was, “My Irish heart is warmed; I’m not now playing for money, but to please myself.” “But could you not play as well during the evening, Talbot, if you wished, as you do now ?”

“No, if you were to hang me. My heart must get warmed, and Irish – I must be as I am this minute.”

This indeed was very signihcant, and strongly indicative of the same genius which distinguished Neil Gow, O’Carolan, and other eminent musicians.

An appeal for continued patronage in behalf of Mr. Dignam, proprietor of the O. P. Tavern, printed in the Freeman’s Journal of April 13, 1812, announced as an attraction that “Mr. Talbot, the celebrated Munster piper, a pupil of the late Cramp, has been engaged to play every evening after eight o’clock (Sunday excepted) at his house, No. 14 Trinity Street.” The notice is addressed “To the Lovers of Harmony.”

Though blind, Talbot used to employ his leisure hours in tuning and stringing pianos, organs, and mending almost every description of musical instruments that came within his reach. His own pipes, which he called the “grand pipes,” were at least eight feet long, and for beauty of appearance, richness and delicacy of workmanship, surpassed anything of the kind that could be witnessed, and, when considered as the product of his own hands, were indeed entitled to be ranked as an extraordinary musical curiosity.

This talented blind musician played before George IV and appeared at most of the London theatres, where his perfornianees were received with the most enthusiastic applause. In person Talbot was a large, portly – looking man, red-faced and good-looking, though strongly marked by traces of the smallpox. He always wore a blue coat, full made, with gilt buttons, and had altogether the look of what is called in Ireland a well-dressed bodagh or “half-sir,” which means a kind of gentleman farmer.

His pipes indeed were a very wonderful instrument, or rather combination of instruments, being so complicated that no one but himself could play upon them. The tones which he brought out of them might be imagined to proceed from almost every instrument in the orchestra – now resembling the sweetest and most attenuated notes of the finest Cremona violin, and again the deep and solemn diapason of the organ. Like very Irish performer of talent that we have met, he always preferred the rich old songs and airs of Ireland to every other description of music, and, when lit up into the enthusiasm of his profession and his love of the country, has often deplored, with tears in his sightless eyes, the inroads which modern fashion had made and was making upon the good old spirit of the bygone times. Nearly the last words Carleton ever heard from his lips were highly touching, and characteristic of the nian as well as the musician: “If we forget our own old music.’, said he. “what is there to remember in its place ?” - words, alas! which are equally fraught with melancholy and truth.

The man, however, who ought to sit as the true type and representative ot the Irish piper is he whose whole life is passed among the peasantry, with the exception of an occasional elevation to the lord’s hall or the squire’s parlor – who is equally conversant with the Irish and English languages, and who has neither wife nor child, house nor home, but circulates from one village or farm-house to another, carrying mirth, amusement, and a warm welcome with him wherever he goes, and tilling the hearts of the young with happiness and delight.

The true Irish piper, Carleton continues, must wear a frieze coat, corduroy breeches, grey woolen stockings, smoke tobacco, drink a tumbler of punch, and take snuff; for it is absolutely necessary from his peculiar position among the people that he should be a walking encyclopedia of Irish social usages; and so he generally is, for to the practice and cultivation of these the simple tenor of his inoffensive life is devoted.

The most perfect specimen of this class Carleton ever was acquainted with was a blind man known by the name of “Piper” Gaynor. His beat extended through the county of Louth, and occasionally through the counties of Meath and Monaghan. Gaynor was precisely such a man as has been described, both as to dress, a knowledge of English and Irish, and a thorough feeling of all those mellow old tints which an incipient change in the spirit of Irish society threatened even then to obliterate.

As before stated, he was blind, but, unlike Talbotys, his face was smooth, and his pale, placid features while playing on his pipes were absolutely radiant with enthusiasm and genius. He was a widower who in his earlier years had won one of the fairest girls in the rich argieultural county of Louth, in spite of the competition and rivalry of many wealthy and independent suitors. But no wonder, for who could hear his magic performance without at once surrendering the whole heart and feelings to the almost preternatural influence of this miraculous enchanter? Talbot? No, no! After hearing Gaynor, the very remem- brance of the music which proceeded from the “grand pipes” was absolutely indifferent. And yet the pipes on which he played were the meanest in appear- ance you could imagine, and the smallest in size of their kind, at that. It is singular, however, but no less true, Carleton says, that he could scarcely name a celebrated Irish piper whose pipes were not known to be small, old-looking, and marked by the strains and dinges which indicate an indulgence in the habits of convivial life.

Many a distinguished piper had the novelist heard, but never at all any whom he could think for a moment of comparing with Gaynor. Unlike Talbot, it mattered not when or where he played; his ravishing notes were still the same, for he possessed the power of utterly abstracting his whole spirit into his music, and anybody who looked into his pale and intellectual countenance could perceive the lights and shadows of the Irish heart flit over it with a change and rapidity which nothing but the soul of genius could command.

Gaynor, though comparatively unknown to any kind of fame but a local one, was yet not unknown to himself. In truth, though modest, humble and unassum- ing in his manners, he possessed the true pride of genius. For instance, though willing to play in a respectable farmer’s house for the entertainment of the family, he never could be prevailed on to play at a common dance, and his reasons, often expressed, were such as exhibit the spirit and intellect of the man.

“My music,” he would say, “isn’t for the feet or the floor, but for the ear and the heart; you’ll get plenty of foot pipers, but I’m none o’ them.” When asked what he thought of the Scotch music in general, he replied, “Would you have me to speak ill of my own? Sure they had it from us.” “Well, even so; they haven’t made a bad use of it.”

“God knows, they haven’t,” he replied; “the Scotch airs, many of them, are the very breath of the heart itself.”

The experience of a night spent by Carleton in his youth at a farmer’s house in Gaynor’s company is too long to be reproduced in full, so we will bid adieu to this paragon of pipers and quote his biographer’s closing paragraph: “Such is a very feeble and imperfect sketch of the Irish piper, a character whom his countrymen love and respect and in every instance treat with the kind- ness and cordiality due to a relation. Indeed, the musicians of Ireland are as harmless and inoffensive a class of persons as ever existed, and there can be no greater proof of this than the very striking fact that in the criminal statistics of the country the name of an Irish piper or fiddler, etc., has scarcely if ever been known to appear.”

The authorship of a great poem or musical composition is the key which opens the portals to the hall of fame. Mr. Hyland’s claims to distinction as an lrish piper, however, do not rest alone on his reputation as the composer of that delightfully descriptive piece of music, “The Fox Chase,” with its imitation of the horns, the tallyho, the hounds in full cry, and the death of the fox, etc. He was an excellent musician, but his performance of “The Fox Chase” is said to have been unrivaled.

Born at Cahir, County Tipperary, in 1780, the same year in which Talbot was born, like the latter also, Hyland lost his sight in early youth, and was apprenticed to a local piper. His talent for music must have been conspicuous to have attracted the notice of Sir John Stevenson, under whom he studied musical theory in Dublin when twenty years of age.

This circumstance brought him into prominence, which, coupled with his wonderfully clever performance. Led to his being “commanded’, to play before King George IV, on his visit to Dublin in 1821. As a mark of recognition, his majesty ordered him a new set of pipes costing hfty guineas. The popularity of the Irish or Union pipes by this time was much enhanced as a result of the improvements effected by Talbot.

If Hyland composed “The Fox Chase,’ in 1799, as stated by an authority, his precocity was remarkable, he being then but nineteen years old and as yet uninstructed by Sir John Stevenson. In according him all due credit, we must bear in mind that the original lamentation, or “Maidrin Ruadh,” consisting of but eight bars, on which the piece was founded, was much older than Hyland’s generation. The renowned performer and composer died at Dublin in 1845.

Elsewhere in this volume will be found several versions of this celebrated piece. Obtained from widely different sources.

Accomplished Irish pipers, with few exceptions, like their predecessors, the harpers, traveled extensively throughout Ireland, Scotland and England, until comparatively recent times. Some followed a regular circuit periodically and returned to their native homes to end their days. Others, again, finding life quite agreeable among the English or Scoteh, settled down permanently in the sister island. Of this latter class was John Murphy, whose talents secured him the enviable position of family piper to the Earl of Eglinton, at Eglinton Castle, Ayrshire, Scotland.

Murphy was evidently no ordinary performer, but a piper and musician of distinction. For in 1820 he published, A Collection of Irish Airs and Jiggs with Variations by John Murphy, performer on the Union Pipes at Eglinton Castle.

Neither history nor tradition shed their illuminating rays on the career of O’Hannigan as far as the present writer was aware until a sketch of his life appeared in The Story of the Bagpipe, by Grattan Flood, recently published.

Some allusions to him have come to hand since then, however.

Born in 1806 at Cahir, County Tipperary, whence Hyland, the famous piper, also hailed. O’lrlannigan was a full-fledged popular Union piper in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Having become blind at the age of eleven, he took the usual course in such affliction, and served an apprenticeship of four years to various Munster pipers.

Following the example of others in his profession who had attained local celebrity he went to Dublin. In 1837 we are informed he tilled an engagement of five nights at the Adelphi Theatre. Seven years later his performance at the Abbey Street Theatre evoked merited applause. He is next heard of at London in 1846, where he remained six years, adding to his fame, and earning the coveted distinction of playing before Queen Victoria and the Prince Consort. And also at an Oxford University commemoration.

Like other exiles he yielded to the desire to return to his native land but died within a year at Bray, County Wicklow, from a stroke of apoplexy.

This surname was as numerous in West Cork and Kerry, as the Smiths were in the old German settlenients in Pennsylvania, and equally as insufficient for the purposes of identification without a subtitle or nickname. The writer in his boyhood days at the Bantry National School could enumerate seventeen branches of the Sullivans, as they were commonly called, and the list was by no means complete.

“Paddy O’Sullivan” is referred to by Grattan Flood as “O’Connell’s famous piper,” although “Mickey” Sullivan, Cumbaw of Castlecove, elsewhere sketched, claimed to be hereditary piper to Daniel O’Connell’s family. At any rate he was taught the art of piping by another Sullivan, his uncle and a band master, piper Mr. Sullivan, ”Coshier,” is mentioned by Lady Chatterton in her Rambles in the South of Ireland, in 1839.

More interested in his personal appearance than in his music, she is silent as to the latter, but describes the former in considerable detail, adding that the nick-name “Coshier” was given to a particular branch of the O’Sullivans from which he claimed descent, for a peculiarity in using a sword in battle. “A most singular figure he was; originally tall and thin, his height is now diminished,” she says, “in consequence of a fall, the result of which was to incline his head greatly to one shoulder, and his jocose countenance has acquired an air of knowing familiarity characteristic of his profession.”

“This excellent performer,” according to Grattan Flood, nourished from 1825 to 1840, but as he could not be induced to wander far from Derrynane, he could not have been the celebrated piper of that name mentioned by Carleton who pur- sued a rival named Reillaghan for eighteen months through the whole province of Munster in order to challenge him to a contest for supremacy.

Not everyone is aware that Thomas Sullivan, a famous military band master, and father of Sir Arthur Sullivan, was also a native of Kerry.

Chronologically this famous blind minstrel is entitled to hrst place among Irish-American pipers, as far as our information goes.

He was a native of Ballinasloe, County Galway, but neither the date of his birth nor any account of his early life has come to our knowledge, except that his tame was widespread even in his youth.

He was well along in years when he came to America, about 1845 and as he had no family, he lived for years with Mr. James Quinn in New York City. Money was showered on him as he played in the streets, so keen was the appreciation of his wonderful music, which we can well believe was voluminous as well as melodious.

This grand old minstrel, towering in talent as well as in physique. Played his way into paradise, where no doubt he was eagerly welcomed, if we are to place any faith in lrish folk lore, for he had his pipes buckled on, with the lively strains of “The Bucks of Oranmore”, rolling in rhythmic tones from the chanter, when the summons to eternity came, as he was entertaining a fascinated audience on the streets of Brooklyn in the year 1855.

In the estimation of Mr. Quinn, a great piper himself, Flannery, of all the pipers he had ever heard, was “the best jig-player that ever laid a finger on a chanter.” ~

“I’ve heard of Flannery from my boyhood,” says Mr. Burke. “He was before my time, but from all accounts he was a great player.”

Concerning his splendid instrument the statement of Michael Egan to Mr. Burke is of unique interest: “I made his pipes in Liverpool. I made him a good instrument, and the right man got it. It made a great name for him and also for me. Until I made Flannery’s pipes, there was no more thought of my pipemaking than there was of Michael Mannion’s of Liverpool, or Maurice Coyne’s of Dublin.” The renowned piper had lived at least ten years in America, and taking into consideration his advanced age on arrival, we can safely assume that his birth may be dated a score or so years back into the eighteenth century.

Flannery’s grand set of pipes, in which Mr. Egan, their maker, took so much pride, became the property of Mr. Quinn, his friend, who honored the old minstrel with a decent burial. Ald McNurney, into whose hands they passed subsequently, found them too large for convenience, so he traded them for a more suitable instrument to Bernard Delaney, who can wake the echoes with them again, although they are far below modern concert pitch.

As a performer on the Irish or Union pipes, the subject of this sketch appears to have been unrivaled in his day, at least as far as musicians of his class had come within the scope of Mr. And Mrs. S. C. Hall’s observation in their compre- hensive travels throughout Ireland in the thirties of the nineteenth century.

Much prominence has been given the celebrated piper and his talents on pages 39 and 40 of Irish Folk Music; A Fascinating Hobby, in connection with the history of the “Fox Chase,” and which therefore need not be repeated here. Much supplementary information, however, concerning this charming character, having since come to hand; it is submitted with great pleasure for the edihcation of those interested in Irish musical biography.

Gandsey was long distinguished as “Lord Headley’s piper”, and it was his privilege for many years to receive instruction beneath his lordship’s roof, where his fine original talents were applied to what was worthy of care and cultivation, and where his attention was riveted to the most exquisite melodies of the mountains and glens.

The venerable bard (who died in 1857 at the patriarehal age of ninety) had much Saxon blood in his veins; for his father was an English soldier, who, being quartered at Ross Castle, fell in love – most naturally – with a pretty Kerry girl.

Having espoused him and his fortune, she followed them to Gibraltar, bequeathing her child James to her mother’s care. An attack of smallpox left him nearly blind, but he could just tell how many candles were lighting on the table. Possibly the skillful surgery of the modern oculist could have effected a cure, as the sight had not been totally destroyed.

The child evinced early genius for music, turning when absolutely an infant the reeds of the lake into musical instruments. When old enough, his grand- father sent him to one of the rustic schools where Latin was taught; and not only the master, but the pupils, loved to instruct and aid the precocious blind boy.

Gandsey possessed original talent in many ways. His wit was ready and keen, and he threw the genuine character of the strain into his performance.

But, gentle reader, from the words of Mrs. Hall you are invited to judge for yourself. “The door opens and the blind old man is led in by his son: his head is covered by the snows of age, and his face, though it retains traces of the fearful disease which deprived him of sight, is full of expression. His manner is elevated and unrestrained-the manner of one who feels his superiority in his art, and knows that if he do not give you pleasure, the fault is not his. Considering that perhaps you do not understand suihciently the beauty of Irish niinstrelsy, he will test your taste by playing some popular air or quadrille; and you already ask your- self if you are really listening to the droning bagpipes. His son accompanies him with so much taste and judgment on the violin as to cause regret that he is not practiced on his father’s instrument, for you would have the mantle hereafter – and long hence may it be – descend upon the son. You ask for an Irish air, and Gandsey, still uncertain as to your real taste, feels his way again, and plays, per- haps, `Will You Come to the Bower?’ so softly and so eloquently that you forget your determination in favor of `original Irish music, and pronounce an `encore.’ Do not, however, waste any more of your evening thus; but call forth the piper’s pathos by naming `Druimin dhu dheelish,’ as an air you desire to hear; then observe how his face betrays the interest he feels in the wailing melody he pours not only in your ear but into your heart.

“What think you of that whispering cadence-like the wind sighing through the willows? What of that line-drawn tone, melting into air? The atmosphere becomes oppressed with grief, and strong-headed, brave-hearted men feel their cheeks wet with tears.

“Said we not that Gandsey was a man of might? The piper feels the eiiect of that air himself; and as he is not a disciple of Father Mathew, a flagon of ale or a mixture of mountain dew will `raise his heart’ and put him in tune for a planxty. There it comes: ringing, merry music – joy giving, light-hearted strain, the overboiling of Irish glee.

“Some of the martial gatherings are enough to rouse O'Donoghue from his palace beneath the lake – one in particular, `O’Donoghue’s whistle,’ is full of wild energy and fire. In but too many instances these splendid airs have not been noted down. The piper learned them in his youth from old people, whose perishing voices had preserved the musical traditions so deeply interesting – even in an historical point of view – to all who would gather from the wrecks of the past, thoughts for the future. There are few of those memories of by-gone days that Gandsey does not make interesting by an anecdote or a legend; and in proportion as he excites your interest, he continues to deserve it.” The instrument on which he performed to the great delight of Mrs. Hall, and in fact all who ever heard him, was a bequest from his friend and instructor, Thady Connor, who asserted Gandsey was the only musician in that part of the country worthy to inherit so precious a gift. When questioned as to the accuracy of the authority for a certain story, the kindly old man smiled and bowed but made no verbal reply. As he did not express any doubt concerning its truthful- ness, we may as well repeat the story as told to the amiable authoress by no less a person that Sir Richard Courtenay himself, in a chapter devoted to “Irish Pipers in Literature.”

Little is known of this migratory Irish piper except that he was a native of Mayo, large in stature, and flourished about the middle of the nineteenth century.

Like so many others of his profession he encouraged the belief that he was indebted to the fairies for his musical excellence.

Finding the life of a traveling piper in Ireland not to his liking, he made his Way to England, where money was more plentiful than in Connacht. Settling down in some town in Lancashire, he secured an engagement to play nightly in a barroom at regular weekly wages, and being a fine piper, even-tempered and accommodating, his employer’s increased patronage proved his popularity.

To Walsh it began to look like a life job. Yet in the midst of our joy there may lurk the germ of trouble, and so it was in this case.

One evening a gang of navvies who came in, seeing a fiddler of their acquain- tance at the bar, rudely ordered the piper to put up his pipes and let the fiddler play.

Under ordinary circumstances he would be well pleased to get a rest while some other musician continued the entertainment, but the insulting tone in which he had been addressed so stirred his hot Milesian blood that he could not overlook the insult.

The herculean piper, six feet three inches in height, deliberately unbuckled his instrument and put it away carefully after detaching the bellows. With the latter as a weapon in his muscular grip he sailed into the crowd and put them to rout, fleeing in all directions for their lives.

After this incident, either from a dislike to the country or the desire to escape the penalties of the law for his onslaught, he returned to his native province, con- tent with whatever the future had in store for him to the day of his death. He settled at Swineford, County Mayo, and taught his art to many pupils who came from near and far for instruction on the pipes.

His method of dismissing his pupils was as unceremonious as his own departure from England. When one had mastered a tune Walsh took the pupil’s hat and hung it outdoors as a signal for the owner to follow it. Without any unnecessary words another aspirant for musical learning was taken in hand and treated similarly.

Down to within comparatively recent times, capable performers on the Union pipes, like their predecessors the harpers, were attached to the households of families of distinction, not alone in Ireland but also in Scotland and England occa- sionally. No little honor and prestige accrued to the position or connection, but to regard the office as hereditary is, we think, claiming too much. Musical talent is more often sporadie than inherited, and the medioerity of famous men’s sons has become proverbial; the dullness of the bard O’Carolan’s only son being a not- able instance.

The subject of this sketch presumably is spoken of in The Story of the Bug- pipe, as one of the last household pipers to the “O’Donoghue of the Glens” in the forties and fifties of the last century, and regarded as little inferior to Gandsey.

Earlier mention is made of Daniel O’Leary, the “Duhallow Piper,” by a traveler who made his acquaintance in the early thirties at the cabin of a herdsman whom the piper visited periodically in his wanderings.

He is described as a dwarfish hunchback, with a knowing cast of countenance and a keen observant eye. After the customary cead mile failte and the ordinary exchange of compliments O’Leary yoked on his pipes to play as a courtesy to the stranger and rendered “Eileen a Roon” and “O’Carolan’s Farewell to Music” with exquisite taste and feeling.

“I have listened to much music,” to quote the traveler’s words, “but Jack Pigott’s `Cois na Breedha’ and O’Leary’s `Humors of Glin’ are in my estimation the ne plus ultra of bagpipe melody.”

A very entertaining but lengthy story of O’Leary’s adventures and experience with the fairies at the fort or rath of Doon will be found in another chapter.

Far more truly can it be said that Galway was the “Mother of Pipers” than that Virginia was the “Mother of Presidents.” Although obviously inadvisable to institute comparisons, yet in introducing the subject of this sketch as second to none in his profession from Galway, or any other county in Ireland for that mat- ter, we are but voicing the opinion which prevails among old-time musicians.

“John McDonough was the best player of Irish music on the pipes known in his day,” Mr. Burke tells us. “He always claimed the parish of Annaghdown, on the banks of Lough Corrib, as his native home (the same in which I was born), but he traveled about from place to place during the greater part of his life.” Even fifty years after his death, which occured in 1857, old people speak of this remarkable piper,s facility in giving to the music an appeal and expression peculiarly his own. An all-around player, capable of meeting all demands, he had a preference for piece or descriptive music.

Much of his time was spent in Dublin, and we are informed by his daughter, Mrs. Kenny, “Queen of Irish Fiddlers,” that while in that city he had for a brief period been engaged by the late Canon Goodnian at Trinity College, either for the purpose of teaching his art, or furnishing entertainment.

In this Mrs. Kenny is simply mistaken, for her father died ten years before the Canon’s appointment to a professorship in Trinity. McDonough may have entertained the faculty or students in earlier years, in Goodman’s sophomore days, or what is more probable he may in his wanderings through Ireland have met the reverend piper when a curate at Berehaven, or Skibbereen, and there given him instruction.

Whatever the occasion may have been, MeDonough’s name was placarded conspicuously in Dublin as the celebrated Irish piper from Annaghdown, County Galway, especially on the bridges crossing the Liffey.

While playing on the streets one evening, to the keen delight of an appreciative audience, some well-to-do gentry who came along were so captivated by his inimitable execution that they took him into a clubhouse or hotel in the vicinity. No doubt he was treated with much liberality, but when he reappeared on the street some time afterwards, it was noticed that he was under the influence of intoxicants. This so angered the waiting audience that they stoned the building, and didn’t leave a whole pane of glass in the windows within reach of their missiles.

In his native province and even beyond it John McDonongh was commonly referred to as “Mac an Asal” from the following circumstance: His father, who was a dealer in donkeys or asses, made a practice of getting “Johnny” to play the pipes along the highway to fair or market while mounted on the back of one of them.

Whether the father’s motive was parental pride in his sonys musical precocity, or a shrewd appreciation of the value of commercial advertising, we are unable to say, but it certainly attracted attention. Later in life, from one of his favorite expressions, he was called “Home with the rent.”

To no class in the community did the terrible famine years prove more disastrous than to the pipers. Those who lived through plague and privation found but

scanty patronage thereafter. “The pipers were gone out of fashion.” as one of them ruefully expressed it, so poor John McDonongh, the peerless piper, finding himself crushed between poverty and decrepitude, took sick on his way back to his native Galway and died neglected and ignored in the Gort poorhouse.

His splendid instrument, made specially for him by Michael Egan, the most famous of all Irish pipemakers, while both were in Liverpool, was treasured by his widow for seven years after his death. Necessity however forced her to sacrifice her sentiments, and though costing originally twenty pounds she disposed of it for a trice to a pipe-repairer named Dugan, of Merchant’s Quay, Dublin.

It appears that Erhnund Keating Hyland and William Talbot were not the only Irish pipers who had the honor of playing for the entertainment of King George IV during his visit to Dublin in 1821.

Kearns Fitzpatrick enjoyed that distinction also, but probably on account of the tones of his instrument being deficient in volume for such a large auditorium, he was not equally successful in appealing to the royal generosity, although his playing of “St. Patrick’s Day” and “God Save the King” was greeted with applause.

How the prestige of having “played before the king” affects a musician’s reputation is well illustrated by a quotation from the letters of a German prince who toured Ireland in I828, addressed to his sister: “In the evening they produced the most celebrated piper of Ireland, Kearns Fitzpatrick. Called the `King of the Pipers,’ having been honored with the approbation of `His most gracious majesty, King George the Fourth.’ Indeed the melodies which the blind minstrel draws from his strange instrument are often as surprising as they are beautiful, and his skill is equal to his highly polished and noble air. These pipers, who are almost all blind, derive their origin from remote antiquity. They are gradually fading away, for all that is old must vanish from the earth.”

The prince. Evidently much impressed with the piper and his instrument, took occasion to cultivate a closer acquaintance. Four days later he writes: “As Fitzpatriek the piper, whom I had sent for to my party yesterday, was still in town, I had him come to play privately, in my room while I breakfasted, and observed his instrument more accurately. It is as you know peculiar to Ireland, and contains a strange mixture of ancient and modern tones. The primitive simple bagpipe is blended with the flute, the oboe, and some tones of the organ, and of the bassoon: altogether it forms a strange but pretty complete concert. The small and elegant bellows which are connected with it are fastened to the right arm by means of a ribbon, and the leathern tube communicating between them and the bag lies across the body, while the hands play on an upright pipe with holes like a flageolet which forms the end of the instrument, and is connected with four or five others joined together like a colossal Pan’s pipe. During the performance the right arm moves incessantly backwards and forwards on the body, in order to fill the bellows. The opening of a valve brings out a deep humming sound which forms an unisona accompaniment to the air. By this agitation of his whole body, while his lingers were busied on the pipes I have described, Fitzpatrick produced tones which no other instrument could give out.

“The sight in which you must picture to yourself the handsome old man with his fine head of snow-white hair, is most original and striking; it is, if I may say so, tragi-comic. His bagpipe was very splendidly adorned. The pipes were of ebony ornamented with silver. The ribbon embroidered, and the bag covered with name- colored silk fringed with silver.

“I begged him to play nie the oldest Irish airs; wild compositions, which generally begin with a plaintive and melancholy strain like the songs of the Slavonic nations, but end with a jig, the national dance, or with a martial air. One of these melodies gave the lively representation of a fox hunt; another seemed to be borrowed from the Hunters’ Chorus in the Freisehutz; it was five hundred years older.

“After playing some time the venerable piper suddenly stopped and said. Smil- ing, with singular grace, `It must be already well known to you, noble sir, that the Irish bagpipe yields no good tone when sober; it requires the evening, or the stillness of night, joyous company, and the delicious fragrance of steaming whiskey-punch. Permit me, therefore, to take my leave.’ “I offered such a present as I thought worthy of this fine old man, whose image will always float before me as a true representative of Irish nationality.” How strange that Irish writers should regard such types of Irish life as Fitzpatrick and his class unworthy of their pens.

The prince had been enjoying the hospitality of a Mr. O’R-- at or near Bansha, Tipperary, when he encountered the grand old minstrel Keans or Kearns Fitzpatrick.

In the early years of the nineteenth century there came from Westmeath into the barony of Carbury, County Kildare, a young piper named Peter Cunningham.

He soon disappeared however, but some years later, after having ranibled all over Munster, came back a finished performer. He settled in the parish of Dunfort at least to the extent that any roving piper can settle. A victim to a peculiar feature of Irish hospitality, he had acquired an unfortunate taste for drink.

On one occasion he visited at Powers’ distillery in Dublin some country friends employed in the establishment, and sampled their wares to the number of seventeen glasses of whiskey at that bout. His only regret on leaving was that he had not drank enough while the liquor was going cheap. To finish the slaking of his thirst he went into a convenient pawn office and pledged a five-pound set of pipes for three tenpennies or half a crown.

In his last years he had of course nothing, and was provided with a lodging in a barn by “Pat” Boylan. Of Killinagh, about four miles from “denderry, Kings County.

Peter was visited by the priest who administered the last sacrament. Being prepared for the long journey he called for his pipes, and after dashing off a few rounds of the “Humors of Glin” announced, “That is the last tune I will ever play,” and soon fell into the sleep which knows no waking.

In the early years of the nineteenth century a piper of some renown named “Jack” Rotchford flourished in the barony of Slieveardagh, County Tipperary. He must have been favored with attributes not especially conspicuous among tradi- tional musicians to have earned the nickname ”Seoghan a Beannuighthe” (Shaun a Vanee) or “John the Blessed.”

All too meagre are the details of his life which have come down to us, but from the text of the following legendary story communicated to us by Mr. Patrick Dunne of Kilbraugh, it can be inferred that he was one of those known as family pipers.

Tradition has it that Shaun was “enchanted, so wonderful was his music, and although he never knew a note, he was able to charm the birds to come and sing near him.”

“Old Butler,” of Williamstown, while entertaining some neighboring gentleman at his residence on one occasion made a bet that he had a better piper than his guest. So Shaun and the other piper met according to the arrangements and played alternately all night and until the break of day, because the judge was unable to decide as to their respective merits. The question of supremacy may never have been determined had not a skylark – proverbial for melody and early rising – lit on the window sill and tapped his approval on a pane of glass when Shaun struck up “The Little House Under the Hill,” and endeavored to accom- pany him with bird music while the tune lasted. Of course Shaun Was proclaimed the winner and “Old Butler” won the bet.

In their complacent yet pitiable egotism pipers of prominence aifected an air of mystery now and then, and encouraged a rather prevalent notion in days gone by that the friendship and intlnence of the fairies had not a little to do with the current of their lives. Shann, who was one of this class, is himself responsible for the following:

One fine morning while watching a cow which needed some care and atten- tion, he thought he may as well entertain himself with a tune or two on the pipes when not otherwise engaged. Choosing the shady side of a rath or fort he sat down and played and sang some favorite airs, for be it understood Cows are by no means insensible to the charms of melody. Loud shouting and elapping of hands greeted the finish of his performance. Startled by such unexpected appreciation he was about to hasten away, when requested to continue the music. After obliging the fairies with another tune-for as no one was in sight who else could it be?-~they cheered again, and as an evidence of their regards, announced, “Go over to your cow now and yon’ll find she has a heifer calf.,’

At a later period, say about the middle of the last century, a piper of at least local celebrity named James Coady, hailing from the same part of Tipperary as “Jack” Rotchford, traveled ahout the country. Whatever virtues he possessed, he was not without a few of the cardinal failings of his fellows. Referring to him by the name which he preferred – Seamus an Choadhe - ‘s wife complained that he gave her no money on his periodical visits home, and alleging that whatever Choadhe would earn during the day Seamus would spend in the night. Drunk or sober he had a great reputation for putting a demoralized set of pipes in good order, a faculty which not all of even the most noted performers possessed.

While making inquiries concerning the historv of “Pat” Spillane, a musical genius who first saw the light at Templetouhy, County Tipperary, it developed that an accomplished piper named Timothy Shelly had kept a public house or tavern in that town for many years.

As his musical performance was restricted to that locality his fame was necessarily eircuniscribed. Intemperance led to his ruin eventually, and he died in the poorhouse about the year 1870, according to Mr. Patrick Dunne, our obliging correspondent.

This great piper’s name, like that of so many others of his profession, would have passed into oblivion but for the linking of his performance with the pranks of Robert Brownrigg. The eccentric “Gentleman Piper” of Norrismonnt, County Wexford.

Kelly, although blind, was one of the circulating pipers of a century ago, and a good one he must have been to have enjoyed the patronage of Mr. Brownrigg.

If further testimony were needed in support of his reputation it Was furnished by a lately deceased eentenarixm of poaching proclivities, who in praising a favorite hound said it had “a tongue as sweet as Hugh Kelly’s pipes,” and that was no small compliment we can well believe.

Not the least distinguished of the many Irish pipers who rejoiced in the patronymic of Farrell or O’Farrell, was one whose story as related by Mr. Flan- agan of Dublin cannot fail to arouse our sympathy regardless of other diversified emotions. Considered from any point of view the outcome reflects anything but credit on those responsible for the poor musician’s predicament.

When our versatile Dublin friend was a young man “learning the pipes” he was occasionally visited by Farrell, whose home was at Shannon Harbor in Kings County. The latter was a fine performer on the double chanter. Ln person he was tall and erect with hair as white as snow, and having served twenty-one years in the army was in receipt of a pension of some six or eight pence a day. “As you are aware,” says our informant, “O’Connell came along addressing the people and levying the Repeal rent to maintain his campaign, though he betrayed no aversion to the fat salaries his relatives were drawing from the government. The Liberator being expected somewhere in Farrell’s locality. The parish priest proposed to the piper that he should take his place in a cart and head the procession with his music.

To this prominence Farrell objected, pointing out that he was dependent to some extent on the government. And that it would he injudicions for him to take part in a demonstration hostile to it.

“Naturally the priest prevailed. And the piper-pensioner. Much against his judgment. Played as requested on the assurance of his reverence that he would see to his safety from unpleasant consequences. When the old soldier was about to be deprived of his pension, the priest on whom he relied told him all he could do for him was to write to O’Connell. ~

“To the appeal made to him by the patriotic priest in Farrell’s behalf, the illustrious Dan. Indifferent to the sacrifice, replied curtly that he `hoped to get Repeal without the assistance of any military men.’” The pension was forfeited. And though the clergyman pursued the course on which he had relied for its retention, poor Farrell in his old age was left to suffer the pangs of poverty as well as the anguish of misplaced confidence.

There was also a piper named Martin Farrell, who circulated in that part of the country. Though a very fair performer “he wasn’t a patch” on the soldier piper of Shannon Harbor.

Immortalized by the eminent George Petrie in the Irish Penny Journal of 1840, “Paddy” Coneely. The Galway piper who flourished in the Second quarter of the nineteenth century, alone of the many accomplished pipers hailing from that county lives in history.

Few indeed are they who do not know that Petrie, artist, antiquary and musician that he was, delighted in nothing more than the indulgence of his hobby of collecting folk music, and it was his desire to increase his store of melodies that brought him to seek the piper’s acquaintance in 1839.

Famous though he was in that part of Connacht, “Paddy” Coneely was not the equal of John Cramp, or Crampton, the Munster piper whose instrument had been secured after his death by the generous Hardiman and presented to his countryman, the Galway piper.

According to Petrie. ‘Paddy’ was simply an excellent Irish piper – inimitable as a performer of Irish jigs and reels, with all their characteristic fire and buoyant gaiety of spirit – admirable indeed as a player of the music composed for and adapted to the instrument, but in his performance of the plaintive or sentimental melodies of his country, he was not able, as Crump was, to conquer its imperfections; he plays them not as they are sung, but – like a piper.

“Yet We do not think this want of power attributable to any deficiency of feeling or genius in `Paddy’ - far indeed from it – for he is a creature of genuine musical soul; but he has had no opportunities of hearing any great performer like that one to whom we have alluded, or of otherwise improving, to any considerable extent, his musical education generally. The best of his predecessors whom he has heard he can imitate, and rival successfully; but still `Paddy’ is merely an Irish piper – the piper of Galway par excellence; for in every great town in the west and south of Ireland there is always one musician of this kind more eminent than the rest, With whose name is justly joined as a cognomen the name of his locality.” “Paddy” was away from home on a tour of the county when Petrie and his party visited the City of Galway; consequently they did not meet until a fortunate coincidence brought them together on the Connemara highway. The piper was on his way home for a change of clothing with the intention ot spending an evening with a party of gentlemen who had engaged him to play at a regatta coming on in a few days. Though quite blind. Yet at any hour of the day or night, he could find his way from his house at Newcastle to any given place in the county. It is said he might often be seen leading another poor blind man by the hand to the latter’s destination.

Despite

his protestations “Paddy” was actually kidnapped and this was

effected only by the seizure of his pipes. His captors explained to

him that the Galway gentlemen could often hear him, while they may

never have the opportunity again of doing so. So he had to come.

Like the American bobolink which sings almost as soon as it is caged, they had “Paddy’, crooning old Irish songs for them and pointing out and even describing all the objects of any interest as they passed along as accurately as if he were blessed with eyesight; though in tact he was stone blind from infancy. More reliable than a barometer, he was an infallible authority on the weather, foretelling a storm in sunshine, and a clearing up on a dismal day, with equal certainty though no indications of impending changes were apparent to others.

After keeping the kidnapped piper with them for two weeks, he was brought home safe and sound and financially better off than if he had kept his engagement with the gentlemen of the regatta.

During the trip, Petrie noted down seventeen of Coneely’s tunes, all of which, with six others scored by Lord Rossmore a few years later, are included in Petrie’s Complete Collection, published in 1902-1905.

The amiable “Paddy” was in tolerably comfortable circumstances Petrie tells ns, having a neat cottage and a few acres of land which he cultivated. He had a great love of approbation – who hasn’t ? - a high opinion of his musical talents, and a strong feeling of decent pride. He played only for the gentry or com- fortable farmer, and would not lower the dignity of his professional character by playing in a tap room or for the commonality, except on rare occasions, when he would play gratuitously and for the sole pleasure of making them happy.

Although he had a wonderful repertory of Irish music; instead of firing away with some lively reel or still more animated Irish jig, he pestered Petrie, in spite of his intensely Irish nationality, with a set of quadrilles or a gallope such as he was called on to play by the ladies and gentlemen at the balls in Galway.

Popular and patronized as he was in his prime, poor “Paddy,” like many other celebrities, outlived his fame. He so far resembled many of his fellow votaries of the muses, who moved in a more exalted sphere, that he rarely “thought of tomorrow.), The famine years proved disastrous to him in many ways. Sad- ness instead of gaiety universaliy prevailed, and music had lost its appeal even were our hero – then in broken health – capable of furnishing it. Paralysis grad- ually sapped his strength and he passed away in 1850, relieved of anxiety for the welfare of his two boys, who were cared for by the Christian Brothers.

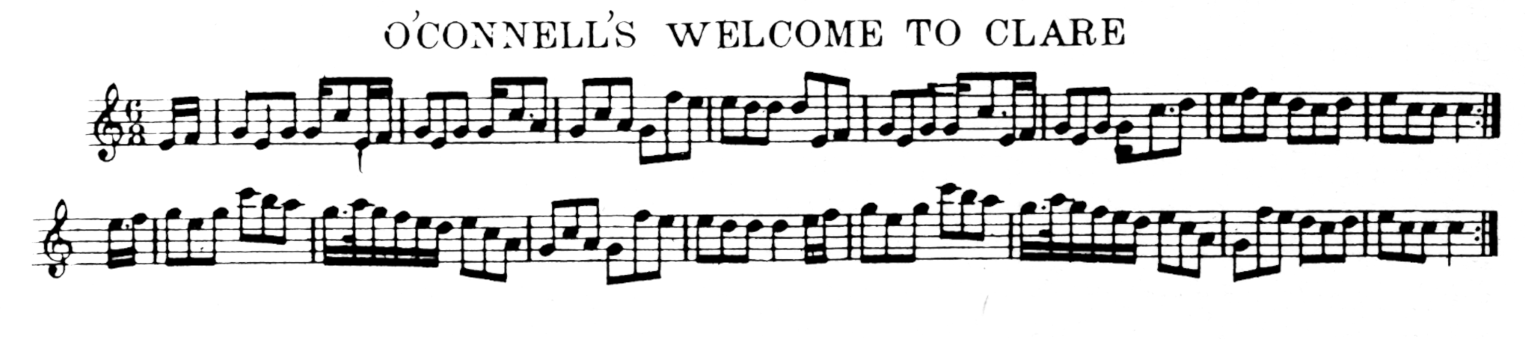

As a specimen of his composition “O'Connel1’s Welcome to Clare,” in 1828, is herewith submitted:

Of the barony of Mohill, County Leitrim, who fiourished in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, was a piper of no ordinary ability. The following story on the authority of Mr. John Gillan of Chicago, who was personally familiar with the circumstances, illustrates his superiority over his contemporaries in that territory.

A few years before the middle of the nineteenth century the estate of Col.

Francis Nesbit at Derrycarn, in southeastern Roscommon not far from Drumod, came into the possession of an Englishman at an auction sale. The purchaser, who was passionately fond of pipe music, gave a barbecue to his new tenants, at which no less than thirty pipers attended. From this number the new landlord selected nine of the best performers to compete for prizes. “Owney” Brennan was pro- claimed the champion after the contest, his rendering of “Lady Kelly’s Reel” being viewed with special favor. One of the Galway Joyces received second prize.

While the third went to a piper who hailed from Drogheda.

Riding in a donkey cart and playing the pipes as if for a wager, it was Bren- nan’s invariable custom to accompany any of his friends or acquaintances leaving for America, from their home to the town of Longford, where they embarked on a boat to continue their journey. He was neither lame nor blind, but took to minstrelsy for a livelihood from natural inclination.

In the parish of Emly – the Imlagh of Ptoleniy -- and barony of Clanwilliam, County Tipperary, a piper of good repute and fine ability named “Ned” Fraher flourished before the middle of the nineteenth century. Not from necessity but rather from musical instinct did he become a piper, for in early life he was in full possession of all his faculties.

After leading the ordinary life of a professional piper for some time, he went to England, where he is said to have won fame and fortune. At any rate he had money and medals when he returned, and there was no one to dispute his claim that he had played before royalty and received the splendid instrument he brought back as an evidence of royal appreciation.

Stricken with sudden blindness, his affliction, idiomatically termed a “blast,” was attributed to the malevolence of the fairies. His misfortune exempted him from the clerical proscription then in force, and he was allowed to play on Sunday afternoons. He was about fifty-three years of age in 1857 when our informant, Mr. Denis Maloney, an excellent musician himself, came to America.

Of Ballylanders, County Limerick, are said to have been excellent performers on the Union pipes. The father, who flourished in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, was blind, and often instead of playing in concert with him Denis danced to his music.

In his young manhood the latter emigrated to England, and being of splendid physique he obtained a position on the police force. An Irish Adonis. A dancer, and musician, he became a prime favorite in short order, and his admirers pre- sented him with a most expensive set of Union pipes, as he had neglected to bring his own with him from Ireland.

As our informant, who had been one of his neighbors at Ballylanders, emigrated to the United States in 1857, the subsequent career of the Lees – father and son – must remain unrecorded.