William Rowsome

[from 'Irish Minstrels and Musicians', Capt. Francis O'Neill, Chicago, Regan Printing House, 1913.]

THE inordinate passion which the Irish have in all ages displayed for music must have eventually produced an eager pursuit of such means as would tend to its gratification. Musical instrument makers were to be found in many of the smallest towns of Ireland, and generally among men of the lowest professions, Lady Morgan tells us in her Patriotic Sketches, published in 1807.

In this work she mentions the case of a poor hedge carpenter in the town of Strabane, County Tyrone, who obtained some degree of excellence in making violins and flutes, built a small organ, and was frequently called in by the most respectable families in the neighborhood to tune or mend pianofortes, harpsiehords, and other instruments.

Another instance was that of a young Connachtman then residing in Dublin, who, though but a common carpenter, made a small piano on which he performed, self-taught in theory of music as in the construction of a musical instrument.

“A remarkably fine-toned organ with six stops,” she continues, “has been lately placed in the Roman Catholic chapel at Mullingar, built by a poor wheelwright, a native of the town. He had commenced as a bagpipe maker a few years before, without any previous instruction, and shortly after completed a good pianoforte.”

The genius to whom Lady Morgan, then Miss Sydney Owenson, refers, was

Originally a maker of household spinning-wheels, and a mechanic of conspicuous excellence, he turned his attention to the making of Union pipes, and became the most famous in that line in Ireland, not alone in his day, but of all time, until Michael Egan, of Liverpool, won recognition and renown in the early forties of the ninteenth century.

Kenna flourished between 1768 and 1794, but the date on which he transferred his business to Dublin cannot be stated.

Judging by the splendid instrument pictured in Grattan Flood’s Story of the Bagpipe which Kenna made in 1770 for John MacDonnell, the development of the Union pipes was far advanced. This instrument, now the property of Lord MacDonnell, late Under-Secretary for Ireland, may be seen at the Dublin Museum, where another set of Kenna’s make is also on exhibition. And, by the way, it may interest the reader to know that John S. Wayland, founder and secretary of the Cork Pipers, Club, rejoices in the possession of a set of Union pipes made by Kenna in 1783, which had passed through the hands of five previous owners.

There having been two makers of bagpipes in Dublin with this surname (probably father and son), the subject of this sketch is generally referred to as “the elder Kenna.”

“The younger Kenna’, flourished in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, and by all accounts he ably sustained the family reputation. He kept shop at No. 1 Essex Quay, Dublin. Mysterious and secretive, “the younger Kenna” was a “close corporation,” and would not allow anyone, idler or stroller, about his place to see him take off a single shaving. A young farmer named Boylan, possessing remarkable mechanical skill, came one day into Kenna’s shop with a chanter and asked him to fit a reed to it, hoping to gain a little knowledge by seeing him work. Kenna, who always maintained a respectable appearance - he wore top boots, if you please - put on his hat and coat, left the shop at once, locked the door, and, turning to Boylan, said: “Come at this hour tomorrow, sir, and your chanter will be ready.’, And so it was, but Boylan was no wiser.

This well-known maker of Union pipes was one of four brothers, respectable young farmers, who lived in the parish of Carbury, County Kildare. A few miles from the town of Edenderry. Maurice took to “playing the pipes’, as a youth, migrated to Dublin, and acquired the tools and business of the “younger Kenna” on the latter’s death. Coyne’s shop was at No. 41 James Street, Dublin.

Instruments of Coyne’s make, of which many are yet in existence, display neat workmanship and, though lacking in volume, are pure and sweet in tone.

The discovery that the magnificent set of Union pipes of peculiar design picked up by Prof. Denis O’Leary in Clare in 1906 was manufactured by the Moloney brothers - Thomas and Andrew - at Kilrush, in that county, presumably solves a puzzling problem.

The trombone slide, which is a conspicuous feature of the instrument, was also a prominent characteristic of the splendid Irish pipes seen in the pictures of Captain Kelly and William Murphy in this volume. As neither of the noted pipemakers - Kenna, Coyne, Harrington, or Egan - turned out instruments of that type, there is nothing inconsistent in attributing their manufacture to the Moloneys.

It was while acting as Gaelic League organizer in 1906 that Professor O’Leary became acquainted with a Mr. Nolan, of Knockerra, near Kilrush, a good amateur piper and an enthusiast on the instrument, though then well advanced in years.

In early life he knew intimately Thomas and Andrew Moloney of the same townland, who made on the order of Mr. Vandaleur, a local landlord, what is claimed to be the most elaborate set of bagpipes in existence. Thomas was a blacksmith and Andrew was a carpenter, but both were great performers on the Union pipes.

According to Mr. Nolan’s story, they did not manufacture many sets of pipes, but they were always most obliging towards the piping fraternity in repairing their instruments.

It may be objected that mechanics of their class would be incapable of turning out such fine technical work, but in view of the fact that Egan, the famous harpmaker of Dublin, was originally a blacksmith, and that the elder Kenna was by trade a wheelwright, there appear to be no just grounds to question the authenticity of the Moloney claims.

When seen by the present writer at Mr. Rowsome’s shop, 18 Armstrong Street, Harold’s Cross, Dublin, in 1906, Professor O’Leary’s treasure was disjointed and apparently long out of use, but it seems Mr. Rowsome experienced no difficulty in putting it in order. It was a massive ebony instrument, the chanter being eighteen inches in length, and, according to its present owner, “of exquisite sweetness and fullness, much superior to an Egan or Harrington chanter.” It has five regulators, with twenty-four keys, and the tones of both basses resemble those of an organ. There are two splendid drones. The tubing and keys are of pure silver and artistically turned out, and the various pipes are tipped with ivory.

Experts estimate the original cost at one hundred pounds, or five hundred dollars.

The date of their manufacture is not known, except that it was early in the nineteenth century, when the makers were in good circumstances. As the young man for whom the instrument was intended met with an injury, it remained on their hands, unsalable because of its expensiveness.

The disastrous famine years ruined the Moloneys and they were obliged to part with their masterpiece for a trifling sum. The purchaser, Mr. O’Carroll, of Freagh, near Miltown-Malbay, was a farmer of independent means, and an excellent performer on the Union pipes. People used to come from far and near to hear him play and to examine the wonderful instrument. He died about the year 1890, and as none of his family could manipulate this “hive of honeyed sounds,” it remained silent as a mummy until Mr. Rowsome restored its voice as before stated.

Many besides the writer were under the impression that John Egan, the famous Dublin harpmaker, who flourished in the early part of the nineteenth century, was also a bagpipe maker.

Speaking of his prominence in his profession, Miss Owenson, afterwards Lady Morgan, says in her Patriotic Sketches: “By an invention of which he has all the merit, he has so simplified the machinery that the springs hitherto found necessary to return the pedals he has laid aside, which renders the harp less liable to get out of order, much easier to repair, and enables the ingenious inventor to sell a pedal harp nearly one-half cheaper than it could be imported.” What more reasonable to suppose than that John Egan was the maker also of the many fine sets of Union pipes on the stocks of which the name “Egan” is found engraved? Few except old-time pipers were aware that the expert piper and mechanic who made those splendid instruments was Michael Egan, of Liverpool, and not John Egan, of Dublin.

This explanation, however, offers no solution of another Egan problem.

On the silver ferrule of the stock of Lord Edward Fitzgerald’s pipes in the Dublin Museum there is engraved the owner’s name, a coat of arms, and the date, “1768. Made by Egan, Dublin.”

Now the question arises, who was this Egan? The writer acknowledges his indebtedness to Grattan Flood for the information that John Egan's father made bagpipes, although Irish literature is silent on that score.

That an able pipemaker of that name once turned out nne instruments in the city of Cork is beyond question, for the name is alluded to by various authorities in that connection. The indefatigable John S. Wayland was unsuccessful in adding to our meagre knowledge. Some light has dawned on us through the medium of John O’Neill, Esq., J. P., of Sarsfield Court, Glanmire, who knew him in his boyhood days.

Harrington, whose first name Mr. O’Neill failed to remember, was the son of a small farmer, but he couldn’t be kept away from music. He went to the city and lived on Hanover Street, where our informant often saw him making pipes.

“Over fifty years ago,” says Mr. O’Neill, “the first exhibition in Cork was held. Harrington made a set of Irish pipes for the occasion. The keys and ferrules were of silver, and he sold them at the exhibition for fifty pounds. At the Munster Feis at Cork, about eight years ago, I complimented one of the pipers, named Cash, from the county of Wicklow, on the beauty of his pipes. He drew my attention to the words, `Harrington, Cork,’ branded on every stick of them. I have an old set of Harrington’s make left me by a piper named John O’Neill.” Discouraged by the direful condition of affairs resulting from the famine, Harrington emigrated to America and all trace of him was lost.

A bagpipe maker of the above name, we are informed by Grattan Flood, occupied the premises at No. 35 Broad Lane, in the city of Cork, about the year 1820, but no further information concerning him is available.

Among bagpipe makers none holds higher rank than the subject of this sketch. His name engraved on the stock of an instrument was a synonym for purity of tone and a guarantee of first-class workmanship since early in the nineteenth century.

Exact dates are unascertainable at this late day, but some leading facts in the life of this hne musician and excellent mechanic can be stated with certainty. He belonged to the town of Glenamaddy, barony of Ballymoe, County Galway, according to Mr. Burke, who associated with him in New York City. John Cnmmings, of San Francisco, who enjoyed his acquaintance at Liverpool away baekin the fifties, says Egan hailed from the village of Cultymaugh, in the County Mayo. How he came to be a piper and pipemaker, or why he chose Liverpool instead of Dublin for his place of business, we have never learned.

It goes to show, however, that Irish pipers existed in considerable numbers in England around the middle of the nineteenth century.

The famous Flannery came to America in the year 1844, or perhaps a year later. The great set of pipes which added to his fame no less than to that of Egan, who made them, he brought across the Atlantic with him. From this date we are justified in assuming that Egan had been established in business at Liverpool probably as far back as 1830, and perhaps earlier.

As stated in the sketch of John Coughlan, the so-called Australian piper, he came to America on the recommendation of the elder Coughlan, with whom he lived for some time. He kept a workshop on Forty-second Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues, New York, until his death, which occurred in 1860 or 1861.

The splendid set of pipes which Charles Ferguson pretended was presented to him on the orders of Queen Victoria was made by Mr. Egan in his shop in New York City during Ferguson’s visit to America.

Then no more than now was bagpipe-making and repairing a lucrative business, it seems, for notwithstanding his skill and popularity, Egan died on the threshold of poverty like that other celebrated piper and pipemaker, “Billy” Taylor, of Phiiadelphia. A benefit party was gotten up for him by his friends in his last illness, and Mr. Burke tells us he remained with him to the last minute.

In discussing the merits of the instrument which he made for Patriek Flannery, Mr. Egan lets us into the knowledge that there was another pipemaker in Liverpool besides himself, namely, Michael Mannion.

The following is his language: “Until I made Flannery’s pipes there was no more thought of my pipemaking than there was of Michael Mannion’s, of Liverpool, or of Maurice Coyne’s, of Dublin.”

When Michael Egan died just before the Civil War, he left no successor to carry on the pipemaking business in New York, so to meet the want, “Ned” White, popularly known as the “Dandy Piper,” started a pipemaking shop at Roxbury, Mass., a suburb of Boston.

Of course, reedmaking and repairs were most in demand, but White turned out quite a number of new sets during his time, of which it can be said that the tones of his drones, if equaled, were never surpassed by those of any pipemaker known to Americans.

Born at Loughrea, County Galway, he came to the United States about the middle of the nineteenth century and settled in Boston. During the years of the Civil War, 1861 to 1865, he was in the zenith of his fame, and conducted a dance hall at Roxbury. Prosperity was loudly proclaimed by his fashionable wardrobe, and such was his pride in his apparel that he never appeared in public nnerowned with a tall silk hat. Hence his nickname, “The Dandy Piper.” “Patsy” Touhey, who knew him well in his old age, says he was “a nice player,” and the fact that John Coughlan, the best piper in Australia in after years, was sent by his father from New York to finish his studies under White, speaks well for his reputation when in his prime.

For many years there lived at No. 842 Greenwich Street, New York City, a good performer on the Union pipes, named Michael Carolan. A native of the County Louth, he was born about the year 1810, and learned the art of pipe- making in his youth. His execution was of the old close-fingering or staecato style, and his training must have been very thorough, for he could play off the printed page with the greatest facility. Long past his eightieth milestone, he died in 1894, in comparative obscurity.

Equally celebrated as a piper and pipemaker in America, “Billy” Taylor, of Philadelphia, came by his talents naturally. Born about 1830 in the historic city of Drogheda, County Louth, where his father was a piper, pipemaker, and organ builder, the son grew up in the trade and continued it until the day of his death, in 1891.

When the elder Taylor came to realize that as a performer he was excelled by his son, he kept right on with the business, but he had lost all taste for playing himself thereafter.

The rapid decline of pipe music in Ireland in the third quarter of the nineteenth century determined William Taylor and his stepbrother, Charles, to emigrate to America and try their fortunes on the other side of the Atlantic.

Their first stand was at New York City, in 1872, and they lived with a friend named Gaffney.

Tom Kerrigan’s pipes were the first made by Taylor in America, and he turned them out in a little workshop fitted up in Kerrigan’s basement, corner of Eighth Street and Avenue D. After a stay ot a year or so in that locality they went to Philadelphia, opened a shop, and gradually built up a business, most of which for a tinie consisted in repairing old sets of pipes. ‘

A short experience of the changed conditions prevailing in the United States convinced them that the mild tones of the ordinary Irish pipes were too puny to nieet the requirements of the American stage or dance hall, being a note or more below concert pitch. Genius that he was, “Billy” Taylor experimented, remodeled and developed a compact, substantial instrument of powerful tone, which blends agreeably with violin and piano. So successful was it in meeting the popular demand that the Taylor type of Irish bagpipe has superseded the old niellowstoned parlor instrument almost altogether.

“Charley” Taylor was a fine mechanic but not a musician. When experimenting, “Billy” would play, while his brother, stationed some distance away, would pass judgment on the music. Both were kept busy, and, though money eanie in liberally, their lrish weakness was taken advantage of by people one would naturally expect to have better principles.

A saloonkeeper who contrived to keep track of their mail instinctively knew when a cheek had arrived. A gang of leeches were promptly on hand to trespass on their hospitality, and, even though the Taylor brothers did not indulge in liqnors which intoxicate, the money was dissipated just the sanie. Oh! When will the Irish misconception of liospitalityy-the national curse-give way to saner customs?

Pouring over manuscript music, of which he had a large store, with a view to improving it, was “Billy's” chief diversion. Occasionally he gave instructions to aspirants, one of his pupils being “Eddie” Joyce, of Boston, who bade fair to rival his teacher when death intervened.

We are credibly informed that Highland pipes, as well as lrish pipes, were manufactured by the Taylors in Drogheda, and it is quite probable such was the case, because Highland pipes were turned out in the Philadelphia shop. Some medals were awarded the Taylors at the Centennial Exposition held in that city in 1875.

The renowned musician and mechanic died in 1901, and his brother “Charley” followed him in about a year, but as neither had ventured to embark on the stormy sea of matrimony there were neither widows nor orphans to mourn their loss.

They were sincerely lamented, however, by all the Irish pipers in the land, for to them the death of the Taylors was a veritable calamity.

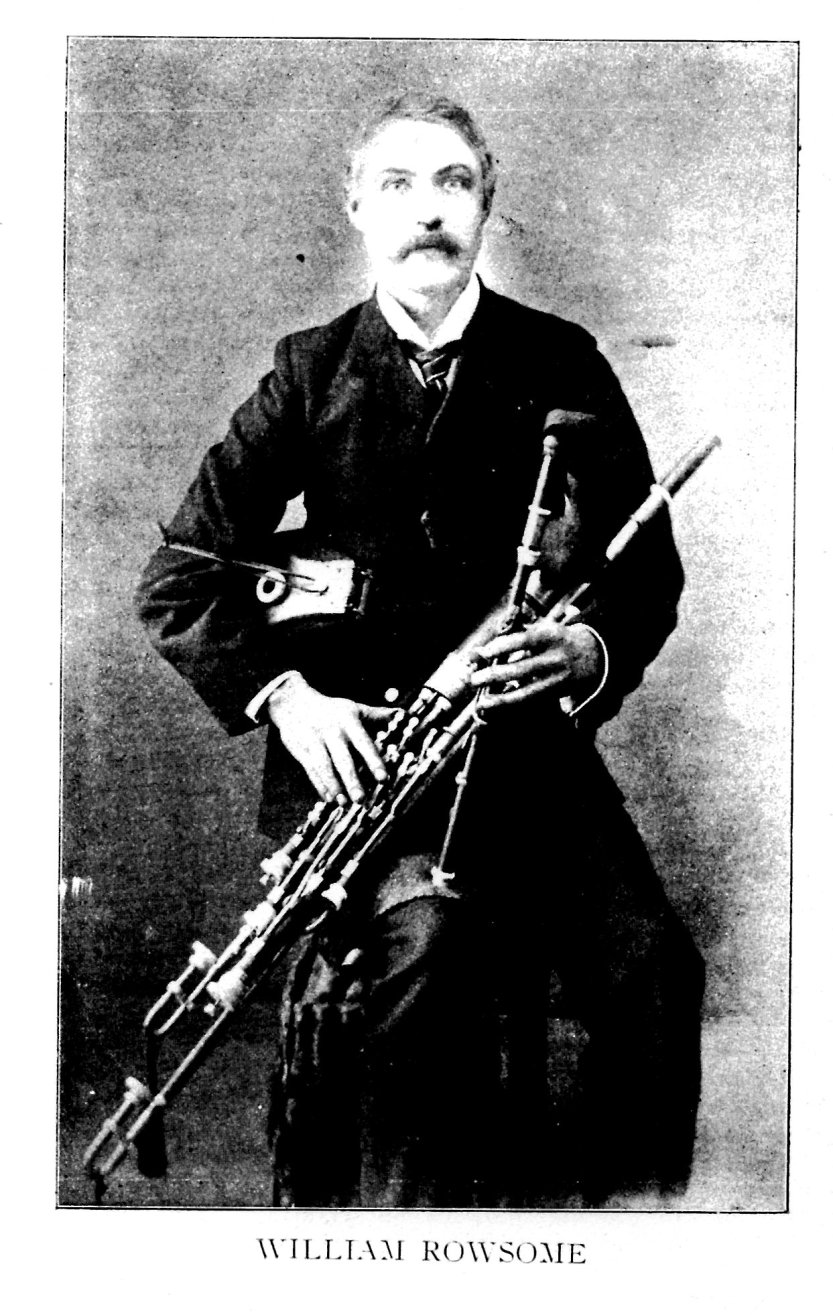

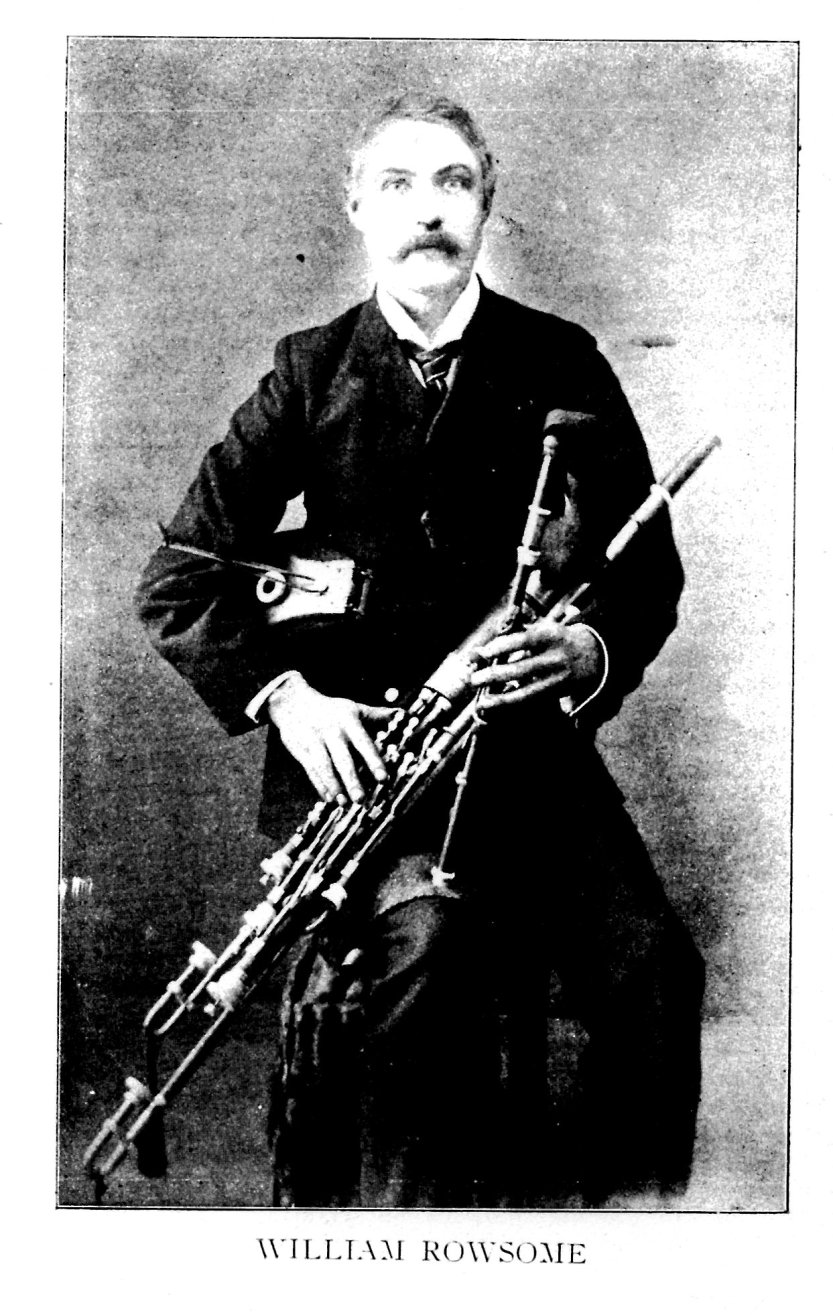

Another notable instance of heredity of musical talent is to be observed in the Rowsome family. Mr. Samuel Rowsome, a “strong” farmer of Ballintore Ferns, County Wexford, was a fine performer on the Irish pipes, by all accounts.

His sons, William and Thomas, of Dublin, need no introduction to the lovers of pipe music in this generation. Perpetuating the name and fame of the family, young Samuel Rowsome, son of William, has already achieved distinction as a piper.

During a brief visit to Dublin in the summer of 1906, the present writer made the acquaintance of the subject of this sketch at his residence, No. 18 Armstrong Street, Harold’s Cross. Being favorably impressed by his manner and music, the visit was repeated in the company of Rev. James K. Fielding, of Chicago, next day. Of course, Mr. Rowsome “put on the pipes” and played his favorite tunes at a lively clip - a trifle too lively for a dancer, we thought. That, however, is a mere matter of opinion. But the spirit of the music was in the performer, unmistakably, for while he touched the keys of the regulators airily and in good rhythm, his eyes sparkled with animation and his whole anatomy seemed to vibrate with a buoyancy which found suitable expression in the clear tones of his chanter. The instrument on which he played and that used by Prof. Denis O’Leary, winner of the first prize at the Munster Feis a few days before, were Mr. Rowsome’s own make. In finish and tone there was no cause for criticism, unless possibly a greater volume of tone might be more desirable in a large hall.

Old-time instruments in all stages of dilapidation were strewn about the shop awaiting repairs, the most remarkable being an immense set made on an original design, and which had lain unused in a Clare cabin for many years.

Always an impulsive enthusiast, my reverend countryman, Father Fielding, was bound to take a shot at it with his ever-ready kodak. Yours truly was persuaded - very reluctantly, though - to hold up the framework of the wonderful pipes to the proper level, it being understood that I was to constitute no part of the target. Standing sideways and leaning backward as far as equilibrium would permit, my outstretched arms presented the derelict instrument in front of the camera. Three months later the morning rnail brought me a souvenir from the reverend photographer in which my distorted likeness was more prominent in the picture than the pipes I had been holding!

Commendably circumspect in his language and reference to others in his profession and trade, during our few hours’ stay, Mr. Rowsome has been almost as fortunate as “Billy” Taylor, of Philadelphia, in winning and retaining the good will of his patrons and associates. The artistic temperament, however, may be accountable for many little misunderstandings which sensitive natures magnify into grievances.

Never was there a greater surprise sprung on “the old folks at home” and the promiscuous array of pipers, fiddlers and fluters at Ballintore and vicinity than the discovery that “Willie” Rowsome had become an accomplished performer on the Union pipes. Having moved to Dublin and married there in early manhood, he was remembered by the people at home in Wexford only as a fine freehand fiddler who could also do a little at the pipes.

Blood will tell, and so heredity asserted itself nd his case. When he paid a visit to the old homestead in the summer of 1911, his general execution and command of the regulators was a revelation to his family and friends. Replying to a question as to the relative merits of William and Thomas Rowsome, John, the senior brother, said: “That is largely a matter of opinion; sorne would rather `Willie’s’ playing, others would prefer `Tom’s.’ I believe `Willie’ is just as good as `Tom,’ and his style is more staccato.”

In the language of an admirer who is himself a versatile musician, “his staccato style is a marvel of dexterity, as it entails an expenditure of muscular energy beyond ordinary manual effort. His tipping and tripling are admirable, and his manipulation of the regulators may well, in these degenerate days of piping, be regarded as an innovation in the art. In playing dance music, which he prefers, his chords, save at the end of the strain, are never sustained beyond the duration of a crochet, so that the bars of his accompaniment in reels and hornpipes are regularly filled with four crochets each, and not infrequently varying to the same number of quavers with equivalent rest intervals alternating.” Much more from the pen of a friendly biographer might be added, but believing it would be injudieions to eater unduly to personalities, especially in the case of a musician still in the land of the living, we must forego the pleasure it would afford us to be more generous with space under different circumstances.

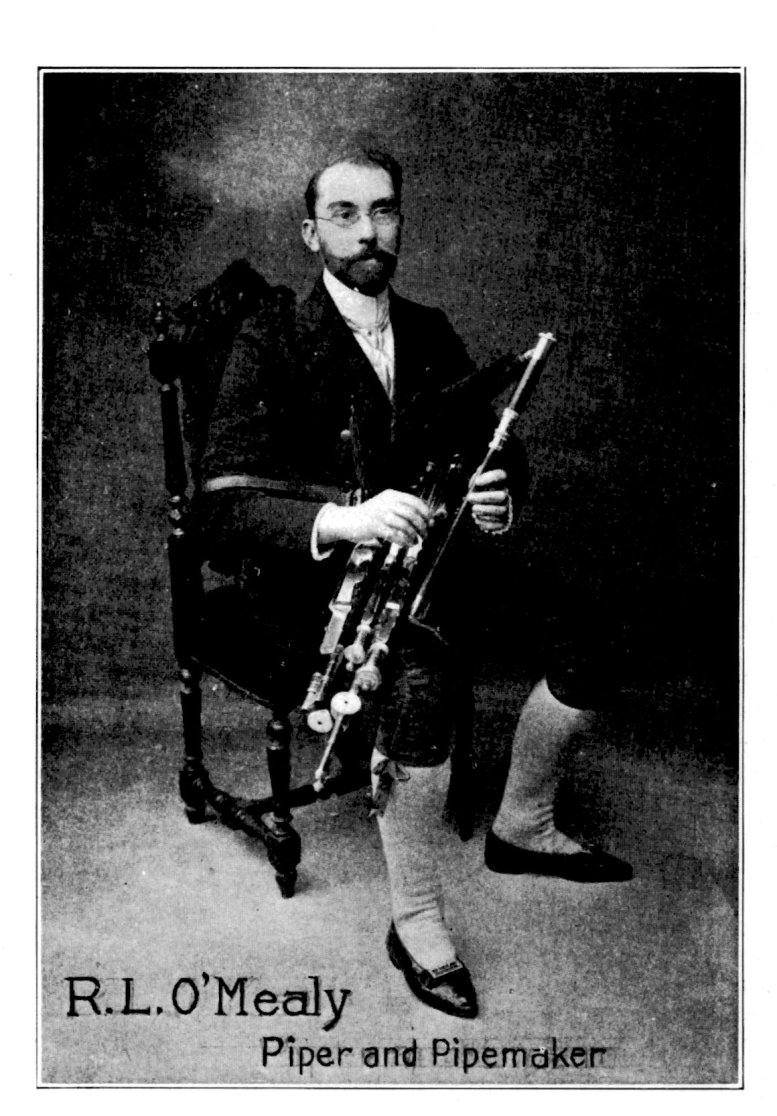

It is with anything but confidence or complacency we approach the task of writing a brief sketch of Mr. O’Mealy, who as piper and pipemaker has earned an enviable reputation in both capacities since the formation of the Gaelic Leagues. Much that would be interesting to the general reader from our point of view, and rather complimentary than otherwise, is omitted in deference to our subject’s wishes. Biography of the living is as much out of place, anyway, as ante-mortum epitaphs, for be it known we are all prone to view ourselves in the delusive mirror of self-esteem.

A man of education and ability, Mr. O’Mealy, now of No. 17 Edinburgh Street, Belfast, was horn generations too late for his merits to be appreciated as they deserve.

A native of County Westmeath, near the birthplace of O’Carolan, where his father, also a fine piper and pipemaker, was a comfortable farmer, O’Mealy traces his ancestry to the historic O’Malleys of County Mayo, where his great grandfather, Thomas, was born. The latter, though a builder by occupation, is said to have been a noted piper and pipenlaker. The trade and talent passed down from father to son through four generations; and as the flattering testimonials of the press in Belfast, Londonderry. Coleraine, Newry, Dublin, and Glasgow, proclaim the excellence of his performance on the Irish or Union pipes, we are furnished with a conspicuous instance in which talent is hereditary.

In his young days Mr. O,Mealy had the pleasure of playing at a concert with the renowned Canon Goodman, who in his opinion was the best piper in the province of Munster.

The young man's talents, though acknowledged, were unappreciated, and, failing to secure a position in any line of remunerative employment in Cork, he directed his course to Belfast, where he was more successful. Realizing that an instrument fuller in tone than the Kenna, Coyne, or Egan type of bagpipe, would be more suitable for modern conditions, he has followed Taylor’s example in raising the tone to concert pitch, and increasing its volume. The old-style bagpipe, be it understood, was much below concert pitch, though very pleasing as a parlor instrument.

Never has a question been raised as to O'Mealy’s excellence as a performer on the Union pipes or the quality of his workmanship. In the manipulation of the regulators, his accompaniment of the chords evokes much flattering comment.

“He is a most interesting psychological subject,” writes one correspondent, “artistic and sensitive; but a decenter fellow than O’Mea1y you could not meet. As a performer of airs, he is most expressive, but as to dance tunes - jigs, reels, and hornpipes - he can turn them off with the greatest rhythmic point and humor. Only to know him socially would not lead one to think him gifted in this way. His playing of the reels is full of that ineffable, buoyant flow that only the best pipers know the secret of. His finger technique is as complete as any I've known, and his use of the regulators. the expressive ringing tones of his treinolo (or, more correctly, his vibrato) are wonderful.

“As a pipemaker he is no less remarkable. All the work - wood work, brazing, turning ivories, curing skins for bellows and bags - is done by his own hands. What he doesn't know about the making and repairing of pipes isn’t much. It was in the blood of the family.”

It is claimed that at the Oireachtas in 1901, and also in 1902, prizes were awarded Mr. O’Mealy for his workmanship, and he is also said to have received an award at the Dublin Feis Ceoil in 1897 for unpublished tunes.

Liberally endowed with the artistic temperament, O'Mealy seems well equipped for his profession. He claims to have worked certain improvements in various parts of the instrument which do away with many of the difficulties with which the learner had formerly to contend. If Irish piping becomes a lost art it will not be for want of skillful pipeniakers in this generation.

Since the death of William and Charles Taylor of Philadelphia in 1901 no capable successor in the art has appeared on the American continent. We emphasize the word capable because an amateur in Massachusetts turns out a set once in awhile which though pleasing to the eye is disappointing to the ear. In fact, the drones of a nice looking set owned in Chicago cannot be fitted with guills at all, by the most expert in that line in the city.

Of Wilmington, Delaware, an excellent turner and general mechanic, got possession of all “Billy” Taylor’s tools and equipment after his death. Mr. Hutton is an enthusiast on bagpipes, both Scotch and Irish, and we are informed enjoys turning out an instrument occasionally, such is his love of everything connected with them. But it takes more than a mechanic to put the true tones in a set of Union pipes, and besides it is an art that all can’t learn, try as they may.

Had there been any scarcity of Union pipes in Chicago in recent years, several of our citizens could have risen to the occasion and supplied the want. Sergt. James Cahill, a native of Kildare, one of the group of pipers in the Irish Music Club, was an expert wood turner. In a workshop attached to his residence he has turned out at least a dozen chanters – flat and sharp – equal to the best, and fully equipped with keys.

Another musician-mechanic to whom nothing comes amiss has devised reamers which bore out chanters as true in tone as any that ever came from the hands of Taylor. In evidence thereof it can be stated that Sergt. James Early and Bernard Delaney, onr celebrated policeman piper, use Mr. Carbray’s chanters in preference to those which belong to their sets of Taylor pipes.

Mr. Carbray, who is a florist in the employ of the West Park Commissioners, Chicago, loves to dally with the lrish pipes. But his execution thereon is not at all comparable to his mastery of the violin. Though he never saw Ireland or the sky over it, being a native of Quebec. Canada, to which his parents had emigrated from the county of Tyrone in the fifties of the last century.

Among the exhibits at the Irish Harp Festival in Belfast in 1903 were “several sets of pipes made by James Williamson, Belfast.” From the press we learn that he “played magnificently on the Irish pipes” on that occasion.

Another exhibit was a “set of Irish Union pipes” attributed to a maker named Kennedy.

In the vicissitudes of human life with its changing moods and fashions, the pipemakers – not so long ago a flourishing fraternity – have dwindled almost to the vanishing point.