[from Irish Minstrels and Musicians, Capt. Francis O'Neill, Chicago, Regan Printing House, 1913]

CHAPTER XXI

FAMOUS PIPERS WHO FLOURISHED PRINCIPALLY IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

This celebrated piper, who is said to have been a native of Limerick, was more fortunate than most members of his profession in being immortalized by Shelton Mackenzie in Bits of Blarney and by Duncan Fraser in Some Reminiscences and the Bagpipe, even though the references to him are disappointingly meagre.

A footnote in the first named work reads, “There is now in New York a gentleman named Charles Ferguson, whose performance on the Irish pipes may be said to equal – it could not surpass – that of O’Donnell.” Ferguson’s pipes are pictured in Duncan Fraser’s work with the following notation:

“THE GREAT IRISH PIPE

WITH DOUBLE BASS REGULATOR AND 27 KEYS

This pipe is made of ebony and ivory with brass mountings, and was said to have been a gift from the late Queen Victoria to one Ferguson, a blind piper in Dublin.” The author adds that Ferguson played in and out of the large hotels in Dublin in the early part of the last century.

To have played before royalty was an honor only exceeded by that of having been presented with an instrument as a mark of special distinction, and though tradition delights in perpetuating stories of such royal favors, few will stand the test of authenticity. Queen Victoria no doubt was endowed with many admirable qualities, but neither generosity nor liberality, especially to an Irishman, can be reckoned among them. In the case of Ferguson, we can clearly acquit her of making any exception in his favor.

Attracted by his splendid execution when playing around the prominent Dublin hotels, Catherine Hayes, the great Irish singer, engaged Ferguson to accompany her on a concert tour of the United States and Canada in 1851. His financial circumstances having materially improved in America, he sought out Michael Egan, the famous pipemaker, who had moved his business from Liverpool to New York, and ordered made the set of pipes supposed to have been presented to him as before stated. Read what Mr. Nicholas Burke has to say on this subject:

“Charles Ferguson, after he came back from San Francisco, lived in Brooklyn, New York. Those pipes you mention in Irish Folk Music – A Fascinating Hobby, that he claims he got presented to him by Queen Victoria, were made for him by Michael Egan in his shop in Forty-second Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues, New York City.

“We had a benefit party for Egan when he was sick a short time before he died. And this was how the tickets were worded: `Benefit party for Michael Egan, the maker of the celebrated Harmonic Irish Union Pipes; also the maker of Professor Ferguson’s pipes, which are supposed to have been presented to him by the Queen of England.’

“Egan was well satisfied with the wording of the ticket. He said he never denied Ferguson’s qualities as a player, and he had no right to deny that he made the set of pipes for him.”

After settling down permanently in Brooklyn, Ferguson and William Connolly played together at picnics and church fairs, Fergusons forte being airs and slow music. Connolly was in demand to play jigs, reels, and hornpipes for the dances, and, in the language of Mr. Burke. “ ‘Tis he could do it to the queen’s taste.”

Ferguson is said to have learned most of his music from Rt. Rev. Dr. Tuohy, who was Bishop of Limerick from 1814 to 1828, a notable performer on the Irish pipes. From this We can account for the pupil’s ability to play the sacred music at the celebration of mass in a Brooklyn Catholic church in later times, and his preference for airs, to the exclusion of dance music.

Eventually, when well advanced in years, he married a wealthy old lady in Brooklyn, who professed a great desire to take care of him, and no doubt she did, for he dropped out of view completely thereafter.

An early settler on the shores of Lake Michigan. James Quinn enjoyed the distinction of being the first Irish piper who became a resident of Chicago.

Famous as a musician and popular as a citizen, he was regarded as an old-timer when the writer made his acquaintance in 1873.

Mr. Quinn was born in the parish of Cloone, barony of Mohill, County Leitrim, about the year 1805, and he died in Chicago in 1890, at a patriarehal age.

Being uncommonly bright and precocious, he attracted the notice of his landlord, Augustus Nicolls, eonnnonly called “Gusty” Nicolls, a noted piper and composer of pipe music, who took him in hand and gave him a thorough schooling on his favorite instrument.

Following some years, experience as a professional piper, Mr. Quinn was engaged as a house-piper by a gentleman in the adjoining county of Cavan.

Every man of prominence prided himself on his piper in those days, for whoever had the best piper was sure to have the most company. Whimsical as prima donnas, pipers were always noted for their eccentricities. No inducement which his employer could offer would restrain one remarkable performer of Mr. Quinn’s acquaintance from taking to the road with the first troop of tinkers that came the way in the spring. The gypsy life which that class of nomadic artisans led in the summer time appealed to him irresistibly, and not until the inclemency of winter weather drove them from the highways did this unconventional piper seek a re-engagement.

Fifty pounds a year and the use of a saddle horse was the ordinary annual allowance for a family piper, and this James Quinn received during his ten years’ stay in Cavan. Letters addressed to him in New York in 1840 indicate his emigration to America before that date. Little is known of his life in New York except that for four years preceding his death the great piper Patrick Flannery lived with him. Mr. Quinn was interested in the livery business after his coming to Chicago, but later he became a coal and wood dealer, in which gainful calling he continued up to the time of his death.

He was commendably liberal with his music in public and in private, and he never failed to entertain his callers to their hearts content. His style of execu- tion was close staccato of the classic Connacht school of piping, and, like most old-time players, he was inordinately addicted to embellishing his tnnes with a surprising number of variations. Many a rare tune has been preserved through him. Besides John K. Beatty, Michael McNurney, afterwards alderman, and Sergt. James Early, who were his pupils, “Pat” Coughlan and John McFadden, famous fiddlers, played in concert with him for many years in Chicago, and consequently acquired and perpetuated his music.

As a wit and a story teller he was in a class by himself. Keen, observant and gifted with a phenomenal memory, we can well believe that his fund of anecdotes was endless. Revered in death as he was loved when living, this typical piper and minstrel, although summoned to eternity over a score of years ago, is still affectionately referred to as “Old Man Quinn” by a large circle of surviving friends, as well as by his numerous descendants.

Most Irish musicians have their specialties, and this characteristic is particularly true of the pipers. Some who can play the most difficult dance music with ease and unconcern seldom attempt to entertain an audience with airs, marches or other slow measures except when called for; while others, on the contrary, who enjoy playing airs and even modern compositions, are incapable of rendering the sprightly dance tunes with that peculiar rhythm and swing which instinctively sets our feet in motion.

The subject of this sketch was a notable exception. He had neither fads nor favorites, for he was equally prohcient and charming in all kinds of music, ancient and modern, which came within the compass of his instrument.

From his own lips in Chicago I learned that he was a protege of “Sporting” Captain Kelly of the Curragh of Kildare. His musical precocity when a boy attracted the Captains attention, and many a time, perched on his patron’s knees, did the youthful prodigy play on his flute for the entertainment of company.

To Mr. M. Flanagan of Dublin, a fine musician himself, we are indebted for some interesting information concerning Hicks’ early life. He was born on the edge of the Curragh, about the year 1825, and was left without a father when quite young, the only son of his widowed mother. His musical proclivities endeared him to his generous patron, who, by the way, was an enthusiastic piper himself, and loved the music of his country as dearly as he loved the turf. What could better exemplify this intensity of feeling than his custom of naming his stud of racers after parts of the instrument, such as Chanter, Bellows, Drone, etc.? The inheritance of musical talent survives in his grand-nephew, Mr. John Kelly Toomey, a Dublin attorney, but it finds expression on the fiddle instead of the Union pipes.

And, by the way, Captain Kelly did not monopolize the sporting blood of the family, for it was his sister, Mr. Flanagan says. Who staked an immense sum and her “coach and four” on Dan Donnelly when he fought and defeated Cooper, the English champion pugilist, on the Curragh of Kildare.

But to return to our subject, “Johnny” Hicks became a piper under the patronage and instruction of Captain Kelly. He turned out to be an apt pupil, and if

we are to judge of the teacher by the style and execution of those who graduated under his tuition, the renowned turfman must be ranked among the best pipers of his day.

How Hicks got started as an independent piper is best told in Mr. Flanagan’s own words, which follow:

“I am sure you will be interested to learn that I was born and brought up Within a stone’s throw of a little wayside public house where Hicks played many a day and many a night. This was before my advent in the family, but the piper lived in the memory of my elders. He was introduced into the neighborhood by a hddler named `Patsy, Kilroy, and the piper soon `cut the roots’ of the fiddler to such a degree that Kilroy bitterly rued his unselfish act. One night the piper and fiddler Were playing in Concert a reel called `Fisher’s Fancy,’ at the public house referred to, when in comes `Bill’ Thoinpson, the local blacksmith and farrier. `Bill,’ who was as fine a specimen of the Irish peasant as I ever laid eyes on. Listened patiently while the musicians played a few rounds of the tune.

Placing his brawny hand on’ Kilroy’s shoulder, he softly said, `Put up that wash-staff attic and let the man play the pipes.,

“The public house which John Hicks had made his headquarters was situated on the Dublin and Galway mail-coach road, about midway between Edenderry and Ennfield. It was kept by the widow Cleary and was a place of great resort, because in those days there was something of a population in rural Ireland.

Hicks must have left the neighborhood in or about 1850. He was then quite a young man and was a promising rather than a finished player. In fact, there was in the parish at the time a much superior piper, `Tim’ Ennis, who afterwards taught me all I know on the instrument. Although denationalized in many aspects, the people of my parish had the old gra for the Union pipes, and a fiddler got but little countenance. Yet when I took up the study as a young fellow there was not another young piper within a radius of ten miles.” “The Kildare piper” must have eonie direct to America in 1850, for he was well known in all the cities along the Atlantic coast almost a generation before his visit to Chicago in 1880, an account of which can be found in Irish Folk Music – A Fascinating Hobby.

His playing was wonderfully even and rhythmical, and the tones were clear, full and melodious. Other performers heard in Chicago at later dates excelled him in brilliant execution and variations, but no piper of our acquaintance was so popular with a mixed, or American audience as John Hicks, because of his versatility in playing all kinds of modern music, including polkas, waltzes, and schottisehes. One great favorite which never failed to please was “General Grant’s Grand March,” a composition which served equally well as a schottische.

He was also a fiddler, and could transpose written music into keys suitable for the pipes when necessary.

He ventured on the stormy sea of matrimony more than once, his second wife being a lady of fortune. Her death before the birth of an heir, under the provisions of the ante – nuptial contract, deprived him of the inheritance.

Clerical in attire and appearance though he was, it did not protect him from being the victim of a fatal assault late one night in the year 1882. He was on his way home to New York after playing at an entertainment on the Jersey side of the Hudson River. Just as he reached the Hoboken ferry-dock someone whose identity was never ascertained struck him on the head with a sandbag.

No attempt was made to rob him, but he died in a short time without regaining consciousness.

In the account of his tragic death, the press honored his music and himself with many flattering paragraphs, due no doubt in some measure to his amiable personality and freedom from those failings which so often mar cordiality in the musical profession.

Among the pipers of whom we have any record, few if any were so successful financially and none possessed the nomadic instinct to such a degree as William Connolly, who was born at Milltown, County Galway, about the year 1839. His father, known as “Liam Dall” or “Blind William”, born at the beginning of the century, was a piper of great repute.

In his young days he went to Liverpool, accompanied by his brother, John, but their experience not being up to their expectations, they decided to cross the Atlantic. While John remained in the United States, William’s restless temperament impelled him to try his luck in Canada. Fortune favored him in this venture, and, finding things to his liking, he tarried in that country for an unusually long time, playing on the steam packets plying up and down the St. Lawrence River.

Having made considerable money, he longed for a change of scene, returned to the United States, and settled in Brooklyn, New York, where he bought a house. This property he disposed of in 1863, fearing he would be drafted into the Federal army, the Civil War being then at its height. Besides, he realized that it was much easier for him to handle a chanter than a rifle, so he lost no time in getting back to Liverpool, in which cosmopolitan city he remained four years.

Before his return to America, when all danger had passed, this inveterate bird of passage took occasion to pay a visit to the old home in Galway. Modesty evidently was not his most conspicuous virtue, for we are told that he engaged a boy to carry his set of bagpipes through Milltown, with a view to impress the people with a due sense of his importance.

Brooklyn, New York, his next destination, soon lost the distinguished piper, for he went to Waltham, Massachusetts, and built a dance hall in which he was to be the great attraction. Golden visions eventually lured him to California, so San Francisco enjoyed a musical treat for some time; but as happiness is always at the end of the rainbow, which recedes as we approach, Connolly retraced his steps to the Atlantic coast. After a brief stay in the East he again headed for the Golden Gate.

Still restless and dissatisfied, he bade a final adieu to California, intent on purchasing Hibernian Hall, Brooklyn; but as his wife would not consent to the sale of her home in Waltham, the project had to be abandoned. Another move was the result, this time to the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he died a few weeks later, after acquiring possession of a prosperous saloon.

Mr. Burke, to whom we are indebted for the above information, says “William Connolly was the best general player on the Irish pipes on either side of the Atlantic.” Michael Egan, the famous maker of the Irish or Union pipes, who knew all the best pipers of his day, was of the same opinion.

His brother John, it seems, was something of a rambler also, for in an article in The Advocate of Melbourne, Australia, issued August I7, 1912, we find that an Irish piper named J. Connolly returned to San Francisco, after a few months’ residence in Melbourne many years ago.” “Patsy’, Touhey, who regarded him as a fair performer, reports that he died about the year 1895 at Milford, Massachusetts.

On the authority of Mr. Burke we are told that this piper was a great performer, excelled only by William Connolly. Little is known of him except that he was a native of Ballinasloe, county of Galway, and that the renowned piper Patrick Flannery was his uncle. After the latter’s death, in 1855, Madden, accompanied by John Coughlan, visited Ireland, where he remained two years before returning to New York.

In Madden’s case, necessity was not the motive for his choice of a profession, for all his faculties were unimpaired. The predilection for music not infrequently proves irresistible, and where social position or some luerative calling presents no hindrance or restraint, the profession of wandering musician is taken up as an agreeable means of obtaining a livelihood.

This great performer on the Irish pipes, who was known among his own people as Cunnigam, belonged to the city of Galway, although Mr. Cummings of San Francisco claims he lived at Athenry, his own native place. Both may be right at different periods. The date of his birth is unknown, but he flourished around the middle of the nineteenth century. According to Mr. Nicholas Burke, he was much given to rambling and was seldom to be found at home. Going from one gentleman’s place to another’s, all over the country, he remained at each for an indefinite period, as did the harpers in their day.

Captain Clancy of the Chicago police, who was born some eight miles northeast of Galway City, remembers Cunnigam’s visits to his father’s house in the fifties. The piper drove his own jaunting car when traveling on his annual summer tours, and he put up for a week or so among his selected patrons.

During his stay at `the Clancy homestead the people flocked from miles around to hear him, and so did the pipers within reach – to listen, learn, and keep still, for they admitted his superiority.

The Captain, who has a clear recollection of the piper and his instrument, describes him as rather tall and thin, with high cheek bones and sallow complexion.

His pipes were longer, slimmer, and softer in tone than the modern concert instrument made by Taylor ot Philadelphia.

‘Twas Cunnigam’s proud boast, and one often repeated, that he received one hundred pounds a year from the Duke of Northumberland for staying at the castle and playing when required for six or eight weeks around the Christmas holidays.

He also claimed to have played before royalty and to have filled engagements at one of the most fashionable of London hotels. His return to his native home in Galway, in prosperous circumstances only in the summer season, gave color of probability to his story, especially as the duke was known to be a great lover of Irish music and a liberal patron of accomplished Irish pipers.

Cunnigam was an incorrigible rambler, and his peregrinations in the year 1861 extended to America, but his travels in the “land of the free” were confined to the cities of Boston, New York, Brooklyn, and vicinity. Restless in spirit as the “Flying Dutchman,” his stay in America was short, for the demon of dis- content seemed to possess him and keep him forever on the move. So he returned to Ireland, but from an article on “The Irish Music Revival” which appeared in the issue of The Advocate, August 17, 1912, we learn that “Owen Cunningham, formerly of Boston, U. S. A., formerly played in the streets ot Melbourne and Sydney in 1808.”

Like Ferguson, Cunnigam was an exception among pipers. A splendid performer, he played airs, marches and descriptive pieces to perfection, yet, to quote the language of Mr. Burke, “he wasnyt much on jigs, reels, or hornpipes.’,

No piper of his day or generation enjoyed such fanie as an accomplished musician as Eugene Whelan, who confined his circuit to his native Kerry.

At Oakpark, a few miles north of Tralee, there lived early in the nineteenth century a rich farmer named Whelan, who was keenly disappointed on the birth of his first-born because it was not a boy. You may be sure that when a second and a third daughter arrived they were anything but welcome. The exasperated Mr. Whelan took no pains to conceal his displeasure at not having an heir to perpetuate his name and inherit his wealth. More than once he told his neighbors that he would rather have three blind sons than three daughters possessed of all their faculties.

His people looked upon his attitude as a defiance of God’s will, which invited merited punishment, and it was no more than they expected when three blind song were born to him following the three daughters. This story, for which our genial friend, Officer “Tim” Dillon, is responsible, can claim more originality than that of Prof. P. D. Reidy, which follows: A beggar woman, accompanied by half a dozen children, sought alms at the Whelan farm-house one day. Being in an ungracious mood at the time, “the woman of the house,” who was not long married, ignored the plea for charity, comparing the beggar woman and her offspring to a sow and her brood. To the proverbial widow’s curse is attributed the subsequent misfortunes of the Whelan family. According to Professor Reidy, three brothers – Maurice, Eugene, and Michael – were born blind, and a sister, Kitty, nearly so. Maurice, who was a first-class hddle player, was living as late as 1840 at least. Michael, who was also a violinist, was the last survivor of the family. Eugene was the most accomplished performer on the Irish or Union pipes Professor Reidy, the renowned dancing master, ever heard. His command of tune was faultless, and his versatility even extended to the flute and fiddle also.

Speaking of his playing of the Ceoil Sidhe (Keolshee), the professor says: “The lights were extinguished. And as I entered the room in the tarmens house I had to study to know where Eugene was sitting, the music was so soft and melodious.” Exhibitions of dancing on the kitchen table by professional or noted dancers were very popular forms of entertainment in Cork and Kerry in former times.

When playing for such experts it was Whelan’s custom to shut off the drones and use the chanter only. Order and quietness were preserved by the old men, so that every tap of the dancers’ performance could be distinctly heard.

When Professor Reidy and Edmund Denis O’Loughlin, another celebrated dancer, gave an exhibition at Mr. Craig’s residence, near Ferranfore, in 1866.

Eugene Whelan, who played for them, was in failing health. And he soon had to take refuge in the Union Infirmary in Tralee, where he did not long survive.

So great was his reputation as a performer when in his prime, that profes- sional pipers from far and near came to hear him. Not only out of curiosity, but also with a view to profit by his example. Conviviality, that bane of professional musicians, led to excesses, and though his end was unhappy he was by no means friendless.

According to Mr. Burke, William Boyle, hailing from the city of Galway, was a fine general player on the Irish pipes and was equally proficient on the fiddle. Caring little for travel, he never went far from home until he canie to America. About 1885 or 1886. being then well advanced in years.

After a short stay in New York City. He settled in Newark, New Jersey, where he died. He kept a dance house in that town. And when Owen Cunnigam would be around they would play together at balls and parties and other entertainments.

Boyle was taught pipe music by Michael Touhey, a famous piper from Longhrea, Galway, grandfather of Patrick Touhey. The renowned American performer. His father, who was a piper also, kept a dance house in the city of Galway.

The maxim that temperance or sobriety tends to prolong life, finds no endorsement in the case of John Williams, a blind piper from the town of Athlone, on the banks of the Shannon. Being a fine performer on the Irish pipes, he was a great favorite with the soldiers at the barracks.

After coming to America he told Mr. Burke that he played for fourteen years in the “canteen.” and during that time he never went to bed a night sober.

Many and many a night he had been picked up. Bag and baggage, pipes and all, and taken home, helplessly intoxicated. He was past middle age when he emi- grated to this country with his wife and daughter, but he had two sons in America years ahead of him. He died at the beginning of this century, a very old man.

This truly great piper, better known as Morris Sarsfield, belonged to Clida, a short distance from the town of Headford, County Galway. How he came by the name Sarsfield is not clear, but it quite likely originated from hero-worship of the famous general. Under the name “Muiruich” (as near the writer can get it) he was known also in that part of the country, natives of which now residing in Chicago remember him by name and reputation.

In the language of Mr. Nicholas Burke. “he was a powerful man and a great player on the pipes.” and we find he had a decided aversion to remaining long in one place. Much of his time was spent in England, but if he happened to be at home at the time, he was sure to he off with the crowd that went harvesting to that country every year.

On one occasion he went to Wales and got along swimmingly with the miners until asked to play the “Collier’s Reel.” Unfortunately. This was a “new one on him.” “Tim” Callaghan’s excuse or proposition to “give them one as good’, was not satisfactory. To be unable to play the tune so named after their trade or calling was to be unworthy of their patronage. And the story goes that Morris was chased out of town for this deficiency in his repertoire.

Neither the date of his birth nor death can he stated. But it is certain that he flourished in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

More than half a century ago – in 1860, to be exact – the present writer, not yet in his teens, listened for hours with awe and delight to the music of Peter Hagerty’s pipes. Peter “Bawn,” as he was called on account of his fair hair.

Was a tall, dignified man of about fifty years of age. The ravages of smallpox, which destroyed his sight and pitted his face, had not entirely obliterated the comeliness of his classic features.

The “patron” at Colomane Cross, at which he played every Sunday afternoon in summer time, was the event of the week to the peasantry for miles around.

Besides the actual enjoyment of attending it, free rein was given to the pleasures of anticipation and memory. The “Piobaire Ban” was a busy man, for there was no let up to the dancing while daylight lasted, and every dance meant an increase of income to the piper.

Close by, in Crowley’s mointan, those who preferred athletics to music and dancing, indulged in hurling, jumping, and stone-throwing to their hearts’ content, and although Harrington’s shebeen was taking in an odd shilling, there was never a complaint of crime or disorder in connection with those popular peasant gatherings.

Of course the piper was not dependent on the weekly “patrons” for patronage.

His music was much in demand, especially in the winter months, to play at weddings, ehristenings and other festivities, and it was the writer’s good fortune to hear him again, even though his delicious strains were subdued by the stone wall which intervened.

There were great dancers in those days, and they were lavish of their praise of Peter “Bawn” as being the ablest performer on the Irish pipes in the south- western baronies of the County of Cork.

The parish priest, Father David Dore, was a gentleman of the old school.

He habitually wore velvet knee breeches, preached in both Irish and English, lived in peace and harmony with his flock, and died wealthy; but he encouraged rather than interfered with the time-honored customs of the people. His suc- cessor, Father Wall, was of a different type altogether. Austere and puritanical, his coming was like the blight of a heavy frost on a blooming garden. All forms of popular pastimes were ordered discontinued. No more dances or diversions relieved the monotony of peasant life, and the poor, afflicted piper, with his avocation gone, had no alternative but the shelter and starvation of the poorhonse.

Rumor has it that in after years there was some dispute or rivalry as to who should give him his passports to “kingdom come.”

In the days before brass bands put them “out of business” Irish pipers not infrequently enlivened the dull hours with their music and consequent dancing on passenger boats, both in Ireland and America.

Mr. John Connors, the Nestor of our Chicago pipers, lately deceased, played for years on one of the famous Mississippi packets, sailing out of Memphis, Tennessee. Before the Civil War.

In his delightful volume. Seventy Years of Irish Life, Mr. Le Fanu intro- duees to his readers the amiable musician on the “Garry Owen” a boat plying between Limerick and Kilrush in his college days.

On the voyage, which generally took about four hours – sometimes five or more, if the weather was bad – the passengers were cheered by the music and songs of a famous character, one “Paddy” O’Neill, whose playing on the fiddle was only surpassed by his performance on the bagpipes. He was, moreover, a poet and sang his own songs, with vigor and expression, to the accompaniment of his own music.

Rare indeed are men of such versatility, and however willing we may be to concede all that is claimed for him as a piper, fiddler, and vocalist, we must in all fairness acquit him of the accusation of being a poet, on the evidence submitted by Mr. Le Fanu himself.

At what date “Paddy” O’Neill gave up steamboating we are not informed, but we know he had a successor on that line in the person of

commonly known as “Jack the Piper.” Born in the County Limerick, he began his career as a piper, playing on the River Shannon excursion boats between Limerick and Kilrush. It is said he accumulated a lot of money in this way, but, growing tired of the monotony of his daily life, or perhaps the decline of interest in his music, he abandoned his accustomed post on the boat and took to the road as a roving piper, choosing the County of Clare as his held of operations, and seldom going beyond its boundaries for any purpose.

He attended all fairs of any importance, and wherever there was a bit of fun going on “Jack” was sure to be in the midst of the crowd, “standing on one leg,” while the other leg hung on a short crutch which held it in the same relative position as if he were seated, so that the end of the chanter could rest thereon.

Quinlan was a good piper, but the decrepitude of his instrument was a sad handicap to his proficiency. To those who spend their holidays at Lahinch and Lisdoonvarna he was no stranger, and he could often be seen sitting on the wall, squeezing out some lively strains for the boys and girls. To whom nothing is more enjoyable than “to tip the light fantastic toe” to the “merry pipes so gaily O.”

of Monntrath, Queens County, had quite a reputation as a professional piper for at least a score of years in the middle of the nineteenth century, and MICHAEL DUNN,

a well-to-do farmer of Aftaly, near Clonaslee, in the same county, was no less proficient as a performer on the Union pipes. His instrument, a small but neat set made by Maurice Coyne of Dublin, is now in the possession of his son, Capt.

Michael Dnnn. Of the Milwaukee Fire Department, who has inherited his father’s musical taste and talent. In addition, Captain Dunn is an expert and ingenious mechanic in all that pertains to the fittings of the most modern Irish chanter.

whose home was at the Ivy Bridge, a mile or so from Castleisland, County Kerry, is said to have been a very good piper, according to Richard Sullivan of Chicago, who knew him well in the seventies of the last century. In 1869 he played for Prof. P. D. Reidy’s dancing class, the sanie year in which the renowned professor gave an exhibition of artistic dancing at Ballybunnian to the music of “Tom” Carthy’s pipes. Good dancers are keen to appreciate good players, so We feel we are on safe ground when relying on such authority.

“Mick” Scanlan, as he was called, was blind, but he traveled all over With his son “Andy” as his guide and dancer to his music. The professionals who dance on a “slab” on the American stage evidently did not originate that circumscribed footing for their act, for “Andy” Scanlan carried about with him a miniature wooden platform, barely eighteen inches square, on which to display his Terpsichorean abilities. When we come to consider the condition of the highways and fields in Ireland when it rains – and that is often – we cannot but admire “Andy’s” thoughtfulness.

“Jack” Moore, as he was known to his neighbors, did not claim to be a gentleman in the sense that he was an aristocrat or above being engaged in some useful occupation. He was simply a wealthy farmer who lived about one mile from Neweastle-West, County Limerick. He was also an excellent performer on the Irish bagpipes – the best in Ireland, according to his friends – who played in his own home for his own pleasure and the entertainment of his company. He was above playing for money, and that, we believe, is where the line can be drawn between the gentleman piper and the professional. It is related of him that he communicated through the means of his music outside the prison walls with a prisoner closely confined for some political or government offense. At any rate, the intent of Moore’s piping was understood and had the desired effect.

Moore, who owned two line farms, was in the habit of taking a cart-load of butter at a time to the Cork market. His neighbors, among whom he was very popular, always timed their trips so as to accompany him, for, besides enter- taining them at his house the night before their departure, he was liberal on the road, and took care that they were justly dealt with by the butter merchants at the city.

Mr. Dillon, a respected member of the Chicago police, now retired, had the honor of dancing “The Blackbird” and “The Humors of Bandon” to Moore’s music in his boyhood days. Being childless, the farmer-piper willed his hne instrument to his nephew.

The latter, who was not musically inclined, for more than four years did not trouble himself to unwrap the package in which his uncle’s gift had been given him. One night he had a very vivid dream in which the late lamented “Jack” Moore appeared to be much displeased because his pipes had been left so long neglected and unused.

Maurice of course excused himself, as he had never learned to play, but the uncle insisted he could it he tried, giving his diffident nephew to understand that there could be no peace for either while the pipes remained silent and smothered in the green bag.

Maurice awoke, worried and perplexed. Try as he would, he couldn’t fall asleep again. There was nothing else to do but get up, for the impulse was irresistible. ‘Twas long after midnight but yet some time before cock-crow – the weird hours in which the spirits and fairies haunt their former homes – when Maurice put the disjointed pipes together and yoked them on as he had seen his uncle do many a time. To say he felt uneasy and nervous is putting it mildly; but after catching a long breath he pumped the bellows under his arm and com- menced lingering the unaccustomed chanter – Moladh’s buidheachas le Dia! (Praise and thanks be to God). Out came the music in a flood of melody, the same as if old “Jack” Moore himself had them on! To his astonishment, Maurice found he could play like an expert on his dead uncle’s pipes without having been taught at all.

Not satisfied with this instance of musical skill supernaturally acquired, our veracious informant, Mr. Dillon, went on to say that in a week or ten days – he couldn’t say for sure – a circus happened along and, being a little short on talent, the manager prevailed on Maurice Moore to entertain the audience with some music on the wonderful pipes as a special attraction. Maurice had some mis- givings about playing so conspicuously, but the story goes that his performance met all expectations, for the gift with which he had been so suddenly and myste- riously endowed betrayed no evidence of decline or deterioration up to the day of his death, which occurred some forty-odd years ago.

Owen and Patrick R. Bohan, who flourished about the middle of the nineteenth century, were natives of a place called Clonbare, County Galway. Mr.

Nicholas Burke, of Brooklyn, New York, who heard them play in his boyhood, says “they had a great name as Irish pipers.”

Being neither lame nor blind, they enjoyed traveling, not alone in Ireland, but in England. Many trips were made to Liverpool, for that great commercial city was almost as Irish as Dublin, in which they eventually settled down, although “Paddy” spent much of his time in England. Owen seems to have been soon lost sight of, but his younger brother’s name,

has been embalmed in modern literature. An lrish-American writer named Barry, speaking of the modern Irish bagpipes, says: “In its original form it had nothing like the range of capabilities which now enables Mr. Bohun to perform on it not only the `Humors of Ballinahinch,’ `Shaun O’Dheir an Gleanna,’ `Paddy O’Carroll,’ `The Fox Chase,’ and `The Blackbird,’ but serious productions such as Corentina’s song from Dinorah and Bach’s Pastorale in F major.” Corroborating Mr. Barry’s appreciative comment, a Dublin correspondent adds, “In the use of the regulators, Bohan was far ahead of all other players of his day.”

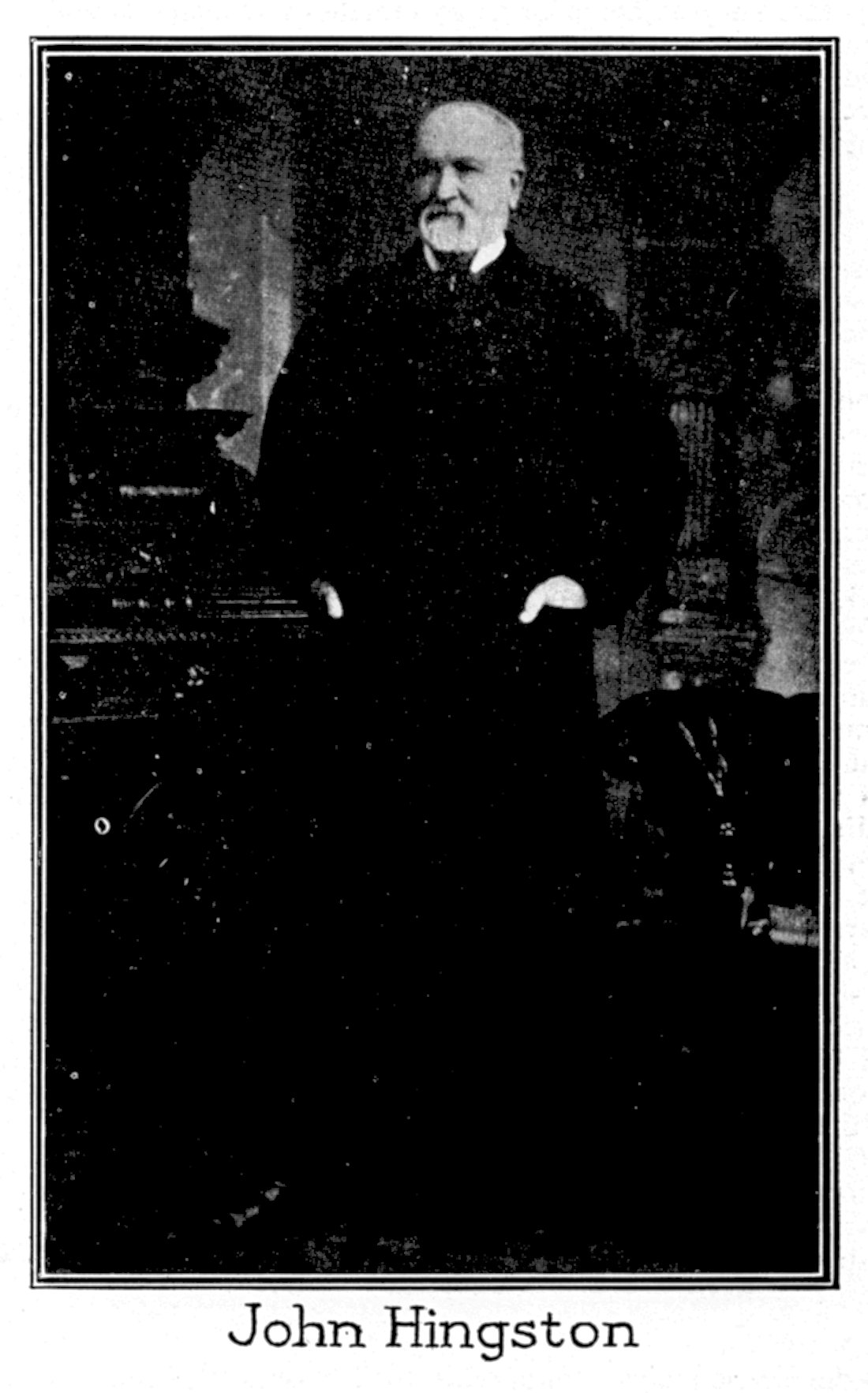

If he ever heard of Father Mathew it is certain he ignored his teachings, consequently he was always a frequent if not welcome guest at the various city police barracks. Early in the year 1867, on a winter evening, Bohan was returning to town after playing in the viceregal kitchen, feeling maith go leor. A young constable, noticing the foreign-looking individual in a slouched hat and wearing chin whiskers, accosted him, and while speaking felt of the green bag, which contained a whooping set of pipes that he took for a new-fashioned pike, in joints, or some other dangerous weapon. A character so suspicious-looking could not be allowed to escape the official vigilance. The new recruit escorted his prize to the barrack, reporting to his station sergeant that he had just captured a dangerous Fenian. His visions of immediate promotion were rudely dispelled, however, When the sergeant, after a glimpse of the captive, exclaimed, “Musha, bad cess to you and your Fenian; sure that’s `Paddy’ Bohan, the piper!” In his old age the minstrel was evidently far from prosperous, and he was indebted for many favors to the generous John Hingston, steward of Trinity College. The latter, who was Canon Goodman’s particular friend, appreciating Bohan's great superiority as a performer on the Irish pipes, fitted him out with a presentable suit of clothing and played in concert with him at the Viceregal Lodge before the Prince of Wales, afterwards King Edward VII.

Although a man of herculean build and a piper of no mean ability himself.

John Hingston many a time danced to the piping of “Paddy” before the inroads of age stiffened the joints of both.

In his prime “Paddy’, Bohan was a perfect piper, and his art was perpetuated in his no less distinguished pupil, “Dick” Stephenson, “The Prince of Pipers.” Not a little whimsical speculation as to the origin and orthography of the surname has been indulged in, but as neither Bowen nor Bohun conforms to the genius of the Irish language, the characteristic hnal as in Bohan is used. The name O’Beoain as written in the Annals of the Four Masters is probably its most ancient form.

From personal knowledge the present writer can testify that “Jimmy” O’Brien was a fascinating performer on the old-style soft-toned Union pipes. We have listened to others who excelled him in execution and versatility, but no one had the faculty which he possessed ot producing combinations and turns by a dextrous movement ot the bottom of the chanter on his knee.

The amiable and modest “Jimmy” was born at Swineford, County Mayo, about 1823. Neither halt nor blind, he took to music through pure love of it, and, being well acquainted with Cribben, a celebrated piper, he became his pupil in early manhood. O’Brien later struck up an acquaintance with “Paddy” Walsh, another famous Mayo piper, but found him far less liberal with his tunes than the good-natured Cribben.

“Paddy” Walsh, although a good teacher of pipe music, would never allow his pupils to beat time with the foot when learning. The test of proficiency was in playing the lesson tune three times over without a slip. When this was accomplished successfully, Walsh, without a word, would pick up the pupills hat or cap and fling it out, as a hint for the owner to follow it and get the rest of the air outdoors.

After graduating, O’Brien emigrated to England, where he obtained employment in a stone-quarry in Yorkshire. An injury to his spine which he sustained

at this work unfitted him for manual labor the balance of his life, so he was obliged to depend on playing the pipes for a livelihood thereafter. He played in taverns and at picnics all over the north of England, particularly in Yorkshire and Lancashire. And even wandered as far south as Devonshire on one occasion.

While sauntering along a highway one day he came to a fine-looking mansion, and, being thirsty, he went up to the hall door and rang the bell. An old lady, whose head was crowned with a wealth ot snow-white hair, responded. When O’Brien announced the object of his call she asked him where he came from.

On learning that he was an Irishman she further inquired if he knew a place called Ballinamuck. Of course he did, for it was close to his birthplace. Then the mystery of her interest in Irish topography was revealed.

Her son, an officer in the English army, was killed in that vicinity a little while before the battle of Ballinamuck, in September, 1798. When the Irish and French troops were marching towards the town, followed closely by the English.

A French soldier dropped out of the ranks, too ill to proceed farther, and crawled behind a stone wall to die. Seeing the English force marching by a short time later, he took deliberate aim at an officer and shot him dead. The victim was the whitewhaired lady’s son.

Notwithstanding a bereaved mother’s cherished grief, O’Brien’s thirst was assuaged with a beverage stronger than water.

In the early sixties lie came to the United States, landing at Portland, Maine, and he played all through the Irish settleinents in that state. Boston, Massachusetts, was his next destination. Having friends and relatives in Chicago, he settled eventually in the western metropolis in 1875 and made the home of Roger Walsh, whom he had known in Portland, his headquarters for a long time. Many a pleasant hour the present writer spent listening to “Jimmy’s” delightful music and memorizing his tunes, many of which were not in circulation until given publicity through our efforts.

At that time Officer William Walsh was but a strippling of fifteen, and ‘twas as good as a play to hear old Roger, his countenance aglow with parental pride, address the boy in alternate terms of encouragement, admonition and endearment as he “trebled and ground” to O’Brien)s piping.

The amiable and accommodating piper had the peculiar and oft-times embarrassing habit of suddenly stopping the music to voice a passing sentiment or

indulge in conversation when elated. After his death, in 1885, his pipes were treasured by John Doyle while alive, and then passed into the possession of Sergt. James Early.

Born somewhere between Ballina and Westport, in County Mayo, this most celebrated of two brothers, in the opinion of some critics, rivaled the renowned William Connolly as a performer on the Union pipes. Mr. Burke says, “I have heard arguments between players about the Wallace brothers; some claimed that Michael Wallace was a better player than Connolly.” In the latter’s biography we have quoted Michael Egan as awarding him the palm of superiority as an Irish piper “on either side of the Atlantic.” As Egan, the piper and pipemaker, was a competent judge, we must regard the question of supremacy as settled.

All that can be said of Frank is that he was inferior to his brother Michael as an Irish piper, but at that he was an excellent performer. As far as known, they traveled together, but never extended their circuit beyond the British Isles.

The Wallace brothers flourished about the middle of the nineteenth century and some years later.

The Wallace brothers and the Bohan brothers, elsewhere mentioned, had assoeiated for years in England with a well-known if not distinguished piper- fiddler of dance hall fame in Brooklyn, New York. An appeal to that thrifty minstrel evoked promises and evasions in plenty, but no enlightenment. But perhaps we were expecting too much, with no reward in sight, from natures grown callous and avaricious by long practice in “passing the hat” on both sides of the Atlantic.

An Irish piper of that name who flourished in comparatively recent times is said by Burke to have been “a good player on the pipes.” Nothing concerning his antecedents is known except that he hailed from the county of Waterford and was born about the year 1838.

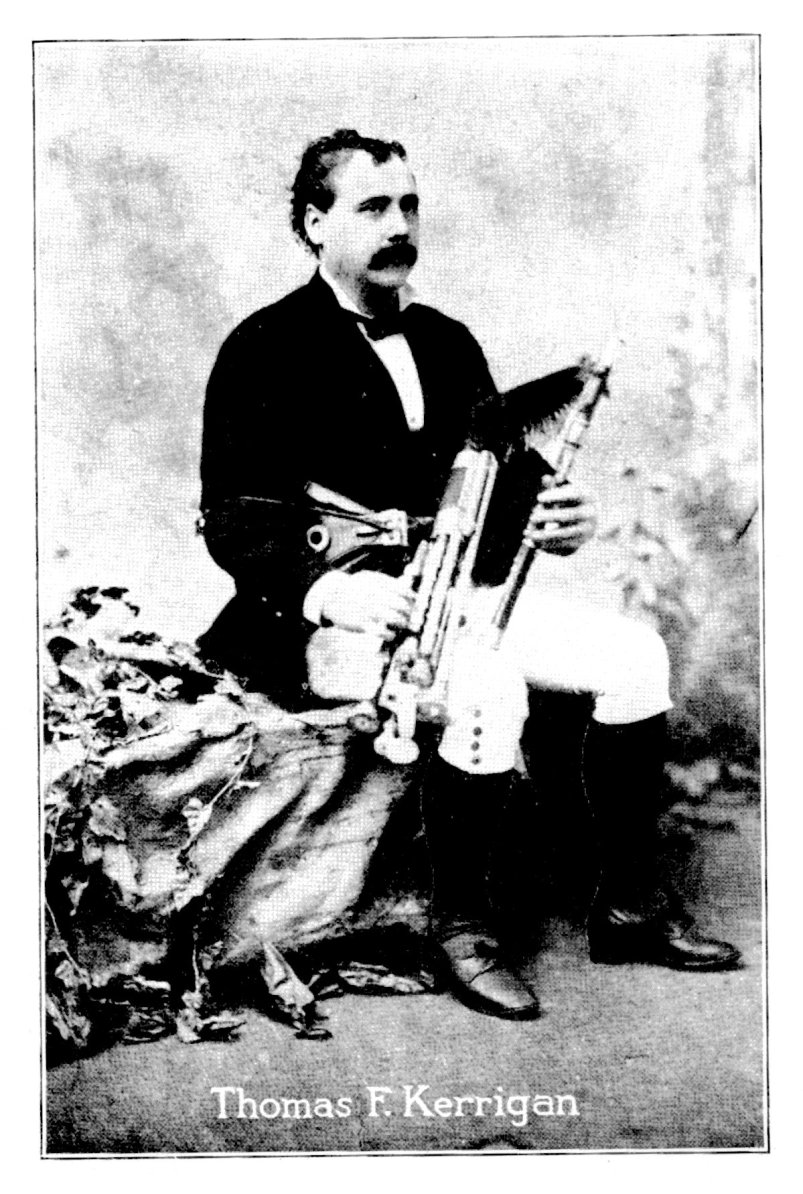

Some years after the Civil War, a man named Reagan, who kept a “Free and Easy” or concert hall, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, decided that an Irish piper would add much to the attractions of his place. Accordingly, he went to New York City and called on Thomas F. Kerrigan, a famous piper who conducted a similar institution at No. 316 West Forty-second Street. Mr. Kerrigan referred him to John Egan, the “Albino piper,” but the latter, not caring for adventures so far from home, sent him to John Cronan, who without hesitation accompanied Reagan back to the “Smoky City,” where he remained for about eight years.

On his return to New York, Cronan formed a sort of partnership with his old-time friend, Egan, and they continued to play together at picnics, parties, and various entertainnients for a long time thereafter. He made his home at his daughter,s house in New Jersey for some years, but he died in 1905 in the City of New York.

Bernard Delaney of Chicago, who met him at Pittsburgh, says he was an amiable, quiet spoken man and a fine, even player on the Union pipes.

Around the early sixties of the nineteenth century there nourished in Tullamore, Kings County, a good performer on the Union pipes named “Jack”

Foraghan. Though a wagonmaker by trade, he was what might be termed a semi-professional, for he played at weddings and christenings and other occasions when favored with an engagement.

He was the proud possessor of an ass and dray of his own, the latter being an object of much interest to his neighbors on account of the facility with which it could be used on sidehill ground. It was provided with an extra wheel of larger diameter than the other two. By substituting the large wheel for a small one on either side, as the circumstances required, the body of the cart was kept pretty much on a level.

Foraghan, who died when but thirty years ot age, had a liberal repertory of dance tunes, and his music was to an appreciable degree the source from which Bernard Delaney derived his inspiration.

“The Albino piper” was a native of Dunmore, County Galway, and like his whilom partner, “Patsy’, Touhey, Was ciotogach, or left-handed. Born about the year 1840, he studied pipe music under the instruction of William Connolly the elder, familiarly known as “Liam Dall” or “Blind William,” and also from the latter’s grandson, John Burke, a capable performer.

Since corning to America most of his time was spent in New York City, the only exception being the years in which he toured the eastern States with “Patsy” Touhey and John Cronan.

Supplementing the latter’s praise of Egan’s proficiency on the Irish pipes, Mr. Burke adds, “He was a grand player and very powerful in his music.” Egan died in New York City about 1897, a comparatively young man.

Touhey is no less eulogistic of his former partner, from whom no doubt he learned some of the artistry of his phenomenal execution on the regulators, and “Patsy’s” estimate can always be relied on as impartial and judicial, although he is charitably silent concerning Egan’s temperamental peculiarities.

In connection with “Paddy” Bohan’s superlative manipulation of the regulators, Mr. Flanagan remarks: “The best piper I ever heard used neither drone

nor regulator – merely the chanter. He must have commenced as a child, so inimitable was his execution. His name was Martin Kenneavy. He enlisted and served six years either in the Ninth or Twelfth Lancers, and on the completion of his military service married one of Bohan’s daughters.

“In 1887, after a long absence from my native land, I heard him play in Gibney’s tavern, at the top of Knockmaroon hill, Phoenix Park, and from him I picked up some fine tunes.”

Kenneavy died at Newcastle-on-Tyne about the year 1890.

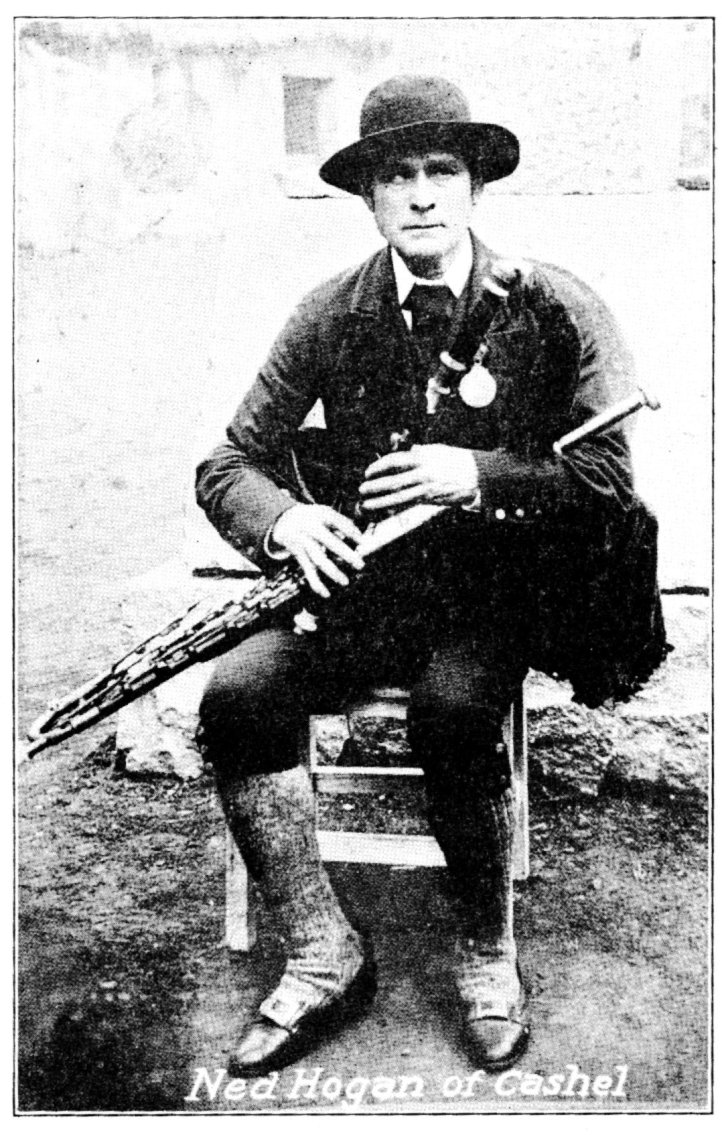

Who has not heard of the Hogans of Cashel, Tipperary, the famous family of pipers and hddlers? Great as was their reputation a generation or two ago, most of what little information concerning them has trickled down to us was vague and legendary rather than reliable.

Out of the gloom of uncertainty we have recently been led by Mr. Wayland of the Cork Pipers, Club, who in his boyhood days enjoyed the acquaintance of one member of the tuneful family. Supplementing his personal knowledge, he has favored us with certain authentic facts derived from his old-time friend, “Con” Dwyer of Cashel.

According to popular report there were four brothers – two pipers and two hddlers – but we find that the numerical strength of the family was underestimated (a very un-Irish error). In reality the father and three sons were noted Union pipers, while two other sons were distinguished fiddlers. All of the brothers but Michael were afflicted with defective eyesight.

The father of this interesting family was a native of Cashel, Tipperary, where his sons also were born. He was a professional piper and flourished in the second and third quarters of the nineteenth century. Thurles, it seems, had been his place of residence for some time, for he died there about the year 1890, at an advanced age, outliving his oldest son by several years, but was buried with his ancestors in his native town.

The eldest of the quintette was not alone a noted piper but a fine fluter and an expert violinist as well. Bernard Delaney, the polished policeman-piper of Chicago, who met “Tom” Hogan at Tullamore, Kings County, in the early sixties, describes him as a tall, dark-complexioned man, always very neat and dressy and wearing a stylish hat. His appearance indicated prosperity, and well he deserved it, for he was equally at home on all kinds of music, ancient and modern, and could play to suit any variety of musical taste. Left to his own choice, “Tom” Hogan ordinarily first played an air, or descriptive piece of music, and followed it up with some spirited dance tune.

John S. Wayland got his first inspiration from “Tom” Hogan’s piping when the latter, accompanied by his son-in-law, “Mickey” Walsh, the dancing-master, used “Johnny” Mickey’s commodious kitchen on the Wayland farm for a dancing- school. The piper died at Cashel, his native place, in 1884. The dancing-master, his son-in-law, who is yet living and long past ninety, it would appeaig was at least as old as “Tom” Hogan, his father-in-law. He claimed to be over ninety years of age when serving as one of the judges of the Feis at Thurles in 1906, and could dance a few steps even then. He Was the recipient of a handsome present in money from Cardinal Vanutelli, Papal Legate, when at Cashel a few years ago, when he learned that “Mickey” Walsh was a member of the Papal Brigade that fought against Garibaldi in 1870. A son of “Tom” Hogan’s who is a splendid fiddler lives in Cashel.

Next in order of primogeniture came “Ned” Hogan, who it is alleged was the best piper in Ireland in his day, according to “Billy” Taylor, of Drogheda and Philadelphia. Be that as it may, there can be no doubt that he enjoyed an enviable reputation as a performer on the Union pipes, although a competent authority still living in Dublin is of the opinion that he had no advantage over “Dicky” Stephenson.

Whether the story, like several similar ones, is apocryphal or not, it is claimed that “Ned” Hogan was presented with a silver-mounted set of pipes by the Prince Consort, grandfather of the reigning King George V. Dublin had been his headquarters for some years, but in 1888 the generous John Hingston, else- where mentioned, fitted him up with a suit of olive green Irish broadcloth cut in the Irish style, put a set of good pipes under his arm, and paid his passage over to the London Exhibition. It is quite possible that the medal which he wore when his picture was taken was won at that time. He settled in Shoreditch, East London, and died there.

From London he came back in a coffin in 1897, his remains being forwarded to Dublin by his pastor, who took up a subscription to defray the expenses. Two daughters, both musicians, were supposed to be living in the capital on that date.

The youngest of the five Hogan brothers was John. Less distinguished, possibly, as a piper than “Tom” and “Ned,” he is also less known to fame. Full forty years ago Mr. John K. Beatty of Chicago heard him play in County Westmeath. His performance was very creditable. Though still living, his present whereabouts is unknown, and being a traveling piper, like so many of his profession, he probably finds life in England or Scotland more to his liking than in his native country.

A typical blind piper belonged in the city of Galway, where he kept a dance house for some years. Emigration, decline of public interest, and other causes ruined a once profitable patronage. Sightless and old and unable to make a living by other means than music, he was obliged, like many another unfortunate Irish minstrel, to take refuge in the poorhouse as his only escape from starvation.

However, his reputation as a fine piper survived his inhumation in this grave of hope and ambition. So when the Gaelic League undertook to revive an interest in native music and language, O’Reilly was taken out by some enthu- siasts and conveyed to Dublin, where, out of practice and all as he was for years, he gained distinction by winning first prize in the pipers’ competition at the annual Feis in 1901.

A Dublin newspaper, describing the Pipers’ Festival in the “Large Concert Hall of the Rotunda,” has the following: “A notable incident was the playing of Mr. Martin O’Reilly, who played a selection entitled “The Battle of Aughrim,” descriptive of the advance, the trumpets of the British, the battle onslaught of the Irish soldiers, and the wail of the women. Aughrim was of course a lost field, but, nothing daunted, the gallant old piper, throbbing with a spirit that might long to play his countrymen into battle, fired them with a stirring and strident version of the victorious march of Brian Boru.” He played in perfect tune and produced marvelous tones on his instrument.

The famous Galway piper was the central figure at several entertainments at various cities for some time thereafter. At the Belfast Harp Festival in 1903 he was the hero of the occasion, his favorite pieces being “The Fox Chase” and “The Battle of Aughrim.” “The wonderful old man,” says one press report, “played the ancient airs with such a feeling expression and profound understand- ing of their suggestions and meanings that he simply took the house by storm.

Later he played for the dancers.”

A half-tone picture of this now celebrated piper from a photograph by Father Fielding in Dnblin was inserted as a frontispieee in O’Neill’s Dance Musir of Ireland in 1907.

It is humiliating to relate that when the excitement subsided, instead of providing suitably for this grand old traditional musician, or establishing him in a way to teach his precious art, we find him back again in the Gort poorhouse: in which ignoble institution he has since died.

And when we come to consider the heartless indifference of the people towards Martin O’Reilly and his talents, can we be blamed if we sometimes question the sincerity of the agitators who have talked themselves hoarse in their advocacy of a regenerated Ireland?

As an object lesson, the ease of Martin O’Reil1y serves well to remind us that a vast gulf still separates theories from practical methods in Ireland.

From far-away Australia earne all the information we possess of Thomas Mahon, an Irish piper, of peculiar celebrity in his day. The interest awakened by Mr. M. P. Jageurs’ article on the Irish Revival in The Advocate of Melbourne last August brought Mahon to the surface from the pool of oblivion.

In a communication to the same weekly a few months later, James Clarke of Albert Park writes: “From childhood to the present date, I have been an enthusiastic admirer of Irish pipe music, a taste stimulated through having lived in boyhood days close to the home of the late Thomas Mahon, `Professor of the Irish Union Bagpipes to Her Most Gracious Majesty, Queen Victoria.’ “ When the late Queen hrst visited Ireland in 1849 a number of Mahon’s friends used their infiuence to obtain for him an introduction, and an opportunity of performing before royalty a selection of national music on a national instru- ment, and they succeeded. However, when the ambitious minstrel arrived in Dublin he found to his keen disappointment that the royal party had left earlier in the day for Balmoral. With a persistence worthy of a better cause, Mahon followed with fevered haste, and delayed only by inevitable formalities, was ushered into the royal presence in dire trepidation, with “his knees bending under him.”

A few kindly words of encouragement from the Queen’s Highland piper, who was present, soon reassured him, so that when her majesty through a page conveyed her request for the “Royal Irish Quadrilles”, “St. Patrick’s Day,” “Garryowen,” etc., he acquitted himself very creditably, but was surprised when he learned that not only the Queen, but the Prince Consort was familiar with the best gems of Irish music.

The Prince Consort, then in his prime, seemed to be enthusiastic over Mahon’s performance, and the Queen, to signalize her appreciation, directed that thenceforth Mahon may bear the proud title as above quoted.

After spending a few weeks at Balmoral Castle, playing for a few hours daily for the royal household, he gave a series of recitals in the principal towns of Scotland before returning to his humble home in the historic little town of Finea, in the county of Westmeath. Mr. Clarke heard him play at a party in 1882, and again in 1889, at which period he must have been over eighty years of age, and though the flight of time had left its stamp on his furrowed face, he was still the brilliant performer on his favorite instrument. When in the zenith of his career he accepted engagements from the wealthier class only, but with increasing years and less prosperous times, his services were available for less favored classes. Two of his sons, after learning to play fairly well, Mr. Clarke tells us, went to America.

Commenting on the respective merits of Mahon, and Coughlan, “the Aus- tralian piper”, he says: “The latter was quite the equal of the former, as a player of dance music, but as an exponent of the higher branches of the art, Mahon, who had through the kindness of a wealthy patron the advantage of a sound musical education, was as might reasonably be expected the more accomplished musician.”

A year or so subsequent to the last date of which Mr. Clarke writes, Mr. Jageurs, author of the article which inspired the discussion, met Mahon and danced a “moneen” jig to his music while on a visit to his native land. The minstrel was then very old and feeble, and though the unexpected coming of an Irish-Australian to that secluded part of Westmeath caused him some little excite- ment, still his infirmities prevented him from playing very much on the beautiful set of pipes he possessed. His jig music. Mr. Jageurs continues, was well ren- dered, but in a reel his memory failed him, with the result that parts of other tunes became intermixed with the original. His forte was still manifest in his execution of descriptive pieces, for the rapid lingering and other quick move- ments incidental to dance music were too much for his enfeebled condition. In the slower musical expression of the melodies, and other almost forgotten ancient airs, he played well enough to convince his visitor that the great reputation he bore in his day, particularly around the “bonnie, bonnie banks” of Lough Sheelin, was well deserved.

The grand old minstrel, whose circuit seldom extended beyond the counties of Westmeath, Longford, and Cavan, died early in the nineties, aged about eighty- five years. In personal appearance his resemblance to Tom Moore was quite remarkable, and the similarity in other respects was no less noticeable, for both had a taste for stealing a few hours from the night as the best of all ways to lengthen their days.

The Union pipes upon which Mahon was heard to the greatest advantage, according to Mr. Clarke, were formerly the property of Sir Godfrey Kneller, one of whose descendants married a nobleman residing near Finea. This is interest- ing if true. Sir Godfrey was born at Lubeck, Germany, in 1648, and died in England in 1723. Taking into consideration that the Union pipes in their most primitive form were but just then developed from the Warpipes, we may be par- doned for regarding the story of the famous painter’s original ownership of Mahon’s instrument as highly improbable.

Shortly after the Cork Pipers Club had been organized in 1898, Jeremiah O’Donovan, its first secretary, mentioned to John S. Wayland, its founder, that a very accomplished old piper named Pat MeDonagh lived in the city of Galway.

O’Donovan, who was an authority on the subject, said he never heard his equal.

Mr. Wayland, whose interest had been aroused, had long wished to meet a piper so highly spoken of. His curiosity was gratified at last on seeing the “man from Galway” facing the judges among at least a score of competitors. On hearing them play Mr. Wayland and Father Quinlan, an amateur piper who sat beside him, agreed that McDonagh was far and away the best of them all.

“When the steward conducting the contest announced that all was over, and the audience began to disperse,” writes Mr. Wayland, “I walked over to McDonagh, a most respectable little man with white hair, and wearing blue smoked glasses; and addressed him in Gaelic, saying how glad I was to meet him, having heard of his ability. I had hardly said that in my opinion he had won first prize, if he got fair play, when the steward having got the verdict from the judges, clapped for silence and to my delight proclaimed the highest award – five pounds – to Pat McDonagh.

“He was certainly a beautiful player, with the sweetest chords I ever heard, and grand `passes, up the scale, and no jarring notes.

“I met him in the street the next day near the Rotunda and was inquisitive enough to ask him where he was going. `Back to Galway,’ he replied. `Why, Mr.

McDonagh,’ I said, `aren’t you a very foolish man not to wait for the Feis Ceoil competition which comes oft in three days ?’ He had intended going home and possibly coming back, but I prevailed on him to remain.” So he did, and won first prize again, a matter of three pounds more. This was in 1903, and before another year had passed Pat McDonagh was numbered with the dead. Another account has it that he died in 1908.

Whatever may have been McDonagh’s career in early life, in later times he kept a small shop or store in the city of Galway, and bore an excellent reputation.

For a man of his rare musical ability his modesty was truly refreshing, and though conscious of his gifts, he was much disinelined to display them away from his own home.

No relationship other than that of surname and nativity existed between him and John McDonough, the renowned piper of an earlier generation.

Unique, even tragic, was the career of “Johnny” Moore, a piper of good repute residing for many years in Brooklyn, New York. He was born in or near the City of Galway about the vear 1834, and was but a boy when his father died.

The widow Moore soon found consolation in a second marriage, her choice being Martin O’Reilly, the celebrated blind piper: and it was from him the subject of this sketch acquired his musical training. Shortly after his coming to America, Moore enlisted in the United States navy and remained in the service for quite a few years.

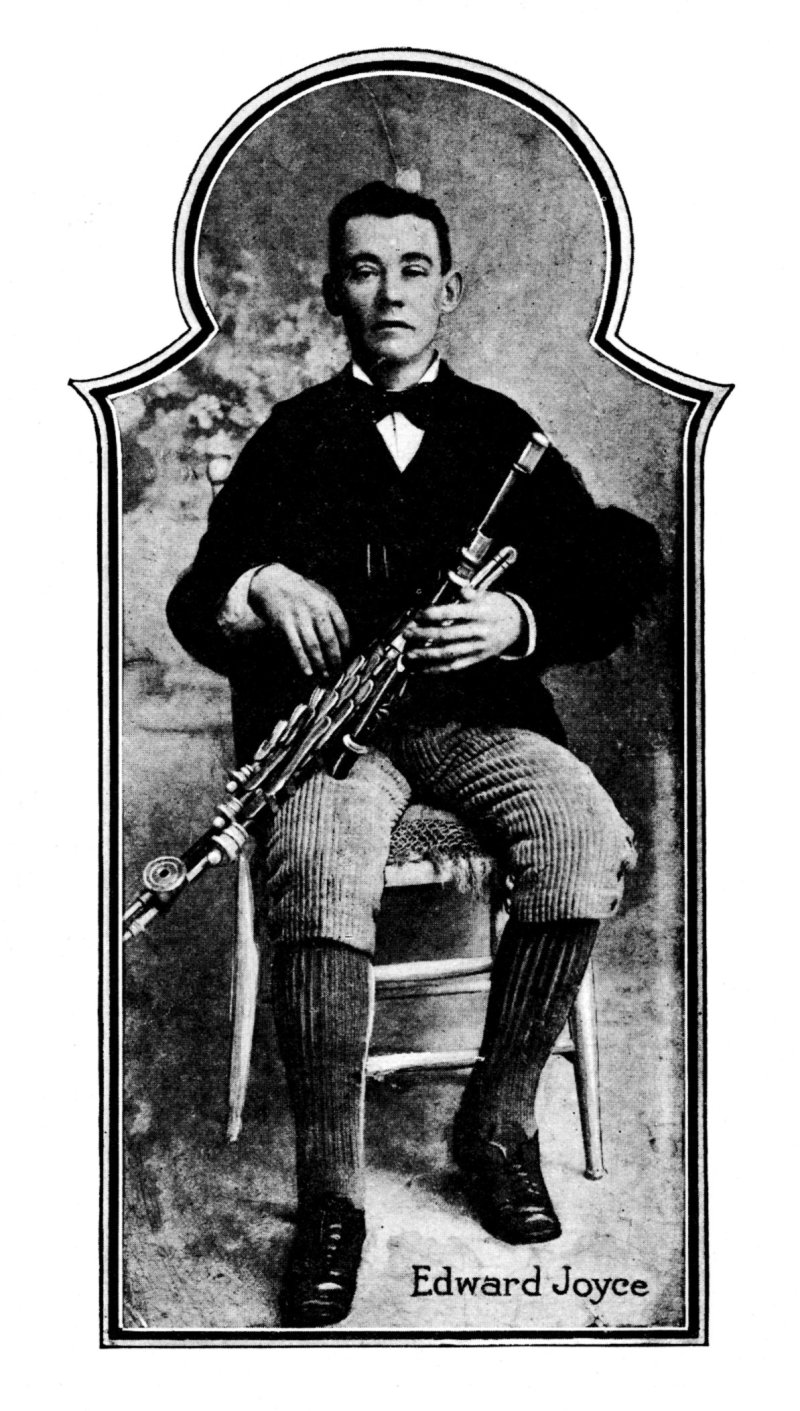

Subsequently he became a professional piper around New York. He accepted an engagement with Powers, Ivy Leaf company, the same with which “Eddie” Joyce and “Barney” Delaney had previously traveled, but took sick at Springheld, Ohio, in 1887, and was sent to a hospital. On Mr. Powers, urgent request, Moore’s place was temporarily filled by Delaney, who was loaned from the Chi- cago Department of Police to tide over the emergency.

While on the circuit after his recovery “Johnny” Moore called on the Delaneys at Chicago later in the season. He was explaining how he had tripped and

fallen on the sidewalk, while bringing home a pail of coal from the fuel yard, when Mrs. Delaney exclaimed in surprise: “A pail of coal! Why, I should think it would be cheaper to buy a ton at a time.” His brow clouded as he glanced at her suspiciously, as if questioning her seriousness, and replied in an injured tone: “A ton at a time! What do you think we are? Millionaires?” As far as known Moore’s life was otherwise uneventful, until in 1894 he decided to return to his native home for the purpose of bringing Martin O’Reilly, his stepfather, back to America with him. The night before his departure from New York he visited “Patsy” Touhey and Patrick Fitzpatrick, brother pipers to whom we are indebted for much of our information. It was remarked that his condition was none of the best, but at that it was by no means alarming.

A week later the newspapers announced that a passenger named John Moore died on the voyage to Ireland, when the boat was within sixty miles of land, and was buried at sea on his own request.

Mr. Fitzpatrick says that Moore was not particularly distinguished for brillianey of execution on the chanter, but in the manipulation of the regulators he had few if any superiors. Often when the reed in his chanter proved refractory or did not “go” to suit him, he would play the whole tune through on the keys of the regulators.

Though but little known to fame the subject of this sketch was a prodigy on the pipes. Like his contemporaries. “Patsy” Tonhey, “Eddie” Joyce, and many others of the fraternity, “Johnny” Murphy come of piping stock. Bartley Murphy, his father, under whose training “Patsy”, Touhey’s musical talents were developed, was himself taught by James Touhey, “Patsy’s” father.

Young Murphy was a Boston boy, born in 1865. Under his father’s instruc- tion he progressed rapidly, and soon was ranked with “Eddie” Joyce, than which no greater compliment could be paid him.

From a former companion, John Finley, the noted dancer and now promising piper. We learn that in 1885 when Murphy was but twenty years old he was matched to play against Joyce for a stake of five hundred dollars, their respective backers being Richard K. Fox of sporting fame and the renowned pugilist, John L. Sullivan. For some reason the contest never came to an issue. Quite likely Murphy’s declining health may have tended to discourage the proposition, for we are told by Mr. Finley. To whom we are indebted for the information, that he died in 1887 lamented by all who knew him.

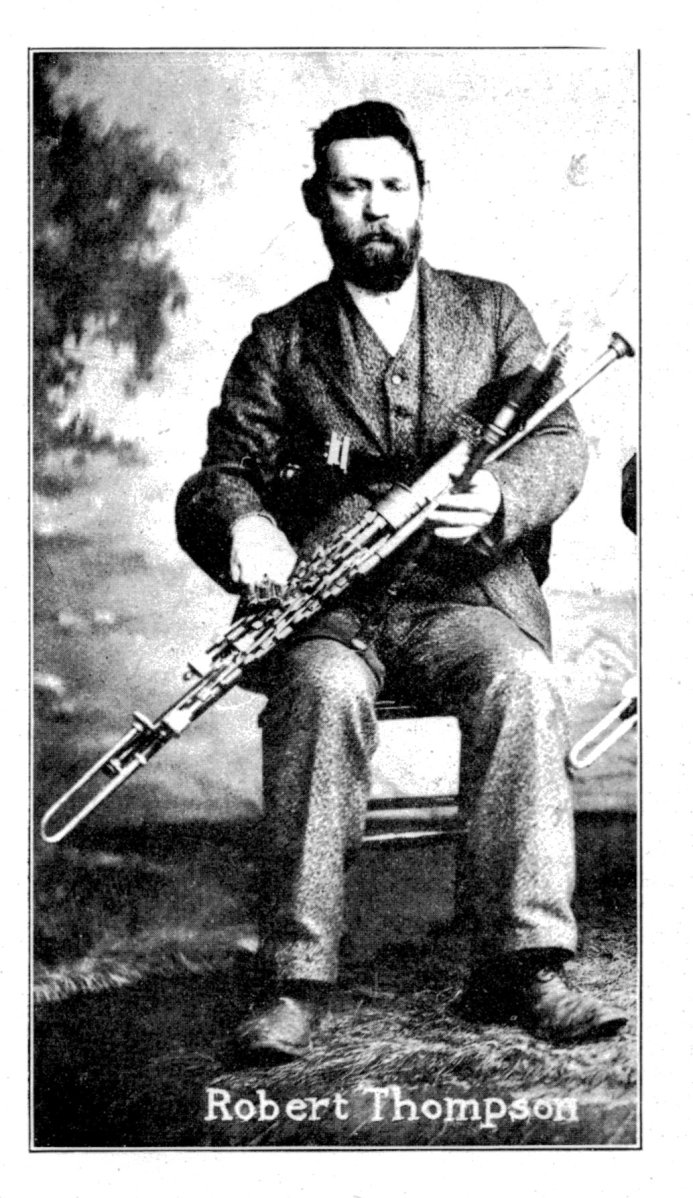

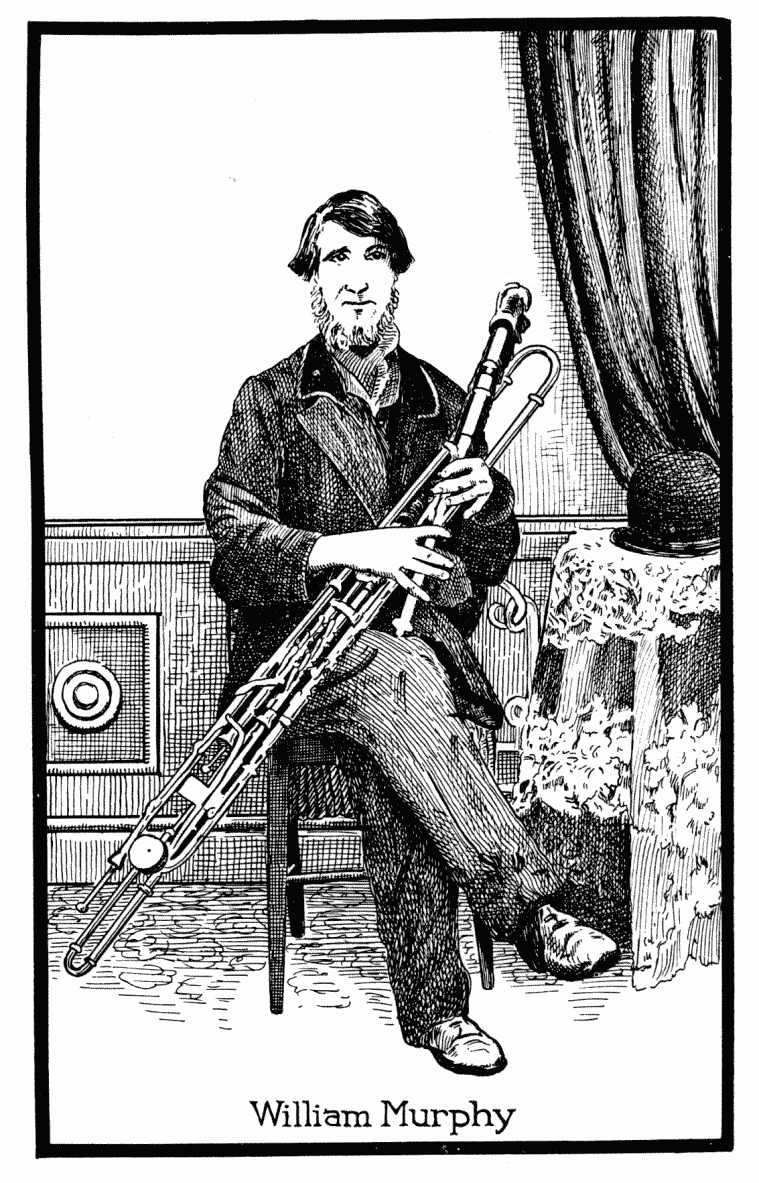

A splendid performer on the Union pipes named William Murphy, commonly known as Liam Mor (Big William) on account of his great height, nourished some twenty-odd years ago on Dublin Hill in the city of Cork. Little else is now remembered concerning him, as Irish piping was then at its lowest ebb in Ireland.

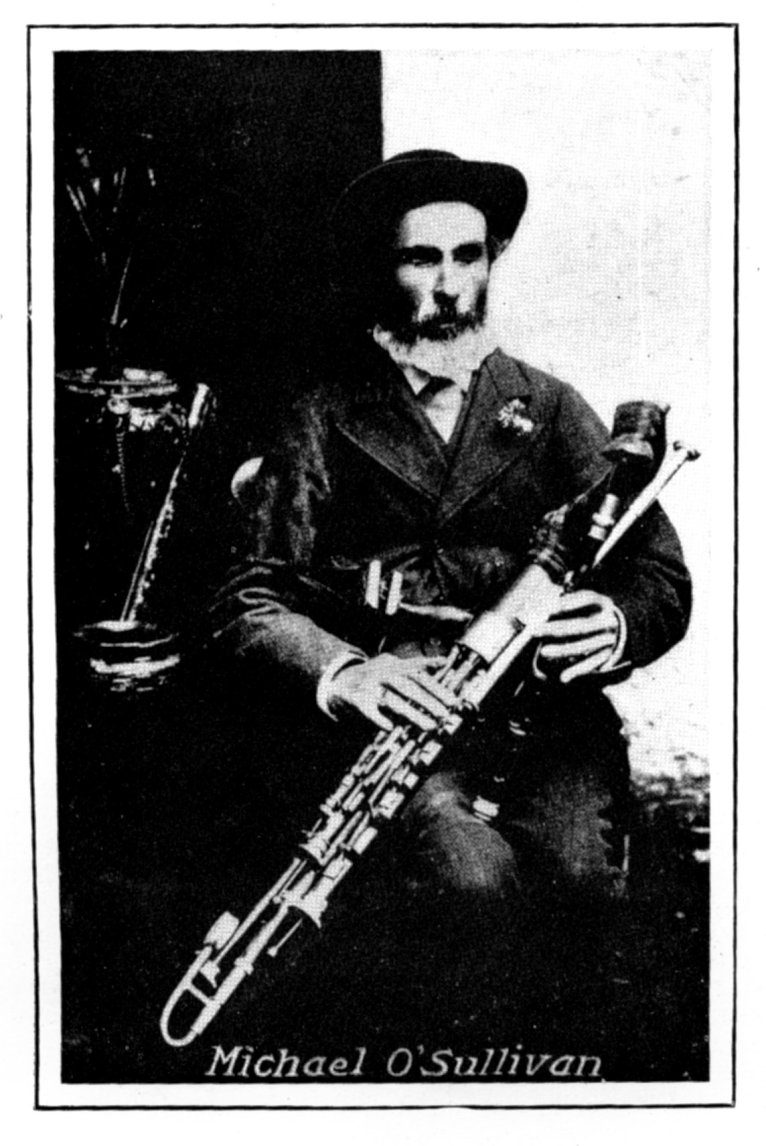

Murphy’s picture, secured through the efforts of our obliging friend Mr. Wayland, reminds us of President Abraham Lincoln, who was also a man of extraordinary stature. His instrument, which was both large and elaborate, is of the same type as those displayed in the pictures of Captain Kelly and Prof. Denis O’Leary, the bass tubes being adjusted with a trombone slide. We have not learned the maker’s name. The easy and confident pose of Liam Mor is seemingly that of a performer who knew his business.

A native of Templetouhy, barony of Kerrin, County Tipperary, had a great reputation as an Irish piper a generation or so ago. According to “Tom” Higgins, a famous fiddler of Hennessy Road, city of Waterford, “Pat” Spillane was the best performer on the Irish pipes he had ever heard. We were apprised that Mr.

O’Mealy, piper and pipemaker of Belfast, entertained a very high opinion of Spillane’s abilities, but our letter of inquiry brought no appreciable information from that quarter.

To the tireless and accommodating John S. Wayland of the Cork Pipers’ Club we owe the intelligence that the subject of our sketch was a fine performer, a thorough musician, and at one time the leader of a band, and spent some time in France.

Though born a “Tip,” he lived much of his life and died in Cork, some fifteen or twenty years ago.

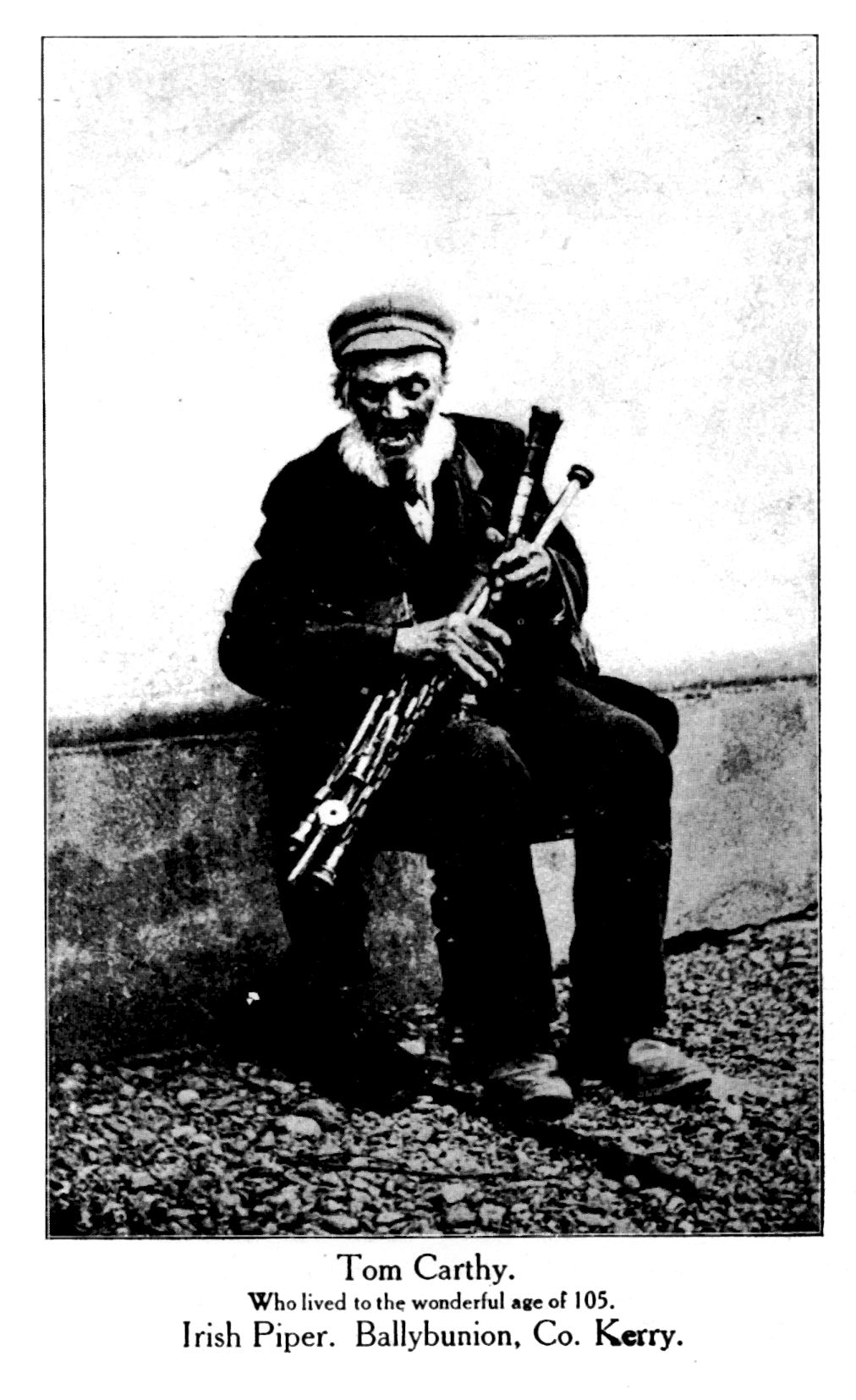

This celebrated centenarian, who lived in three centuries, was born in the year 1799 and died in 1904 at the remarkable age of one hundred and five years. A native of north Kerry, within a mile of Ballybunnian, he lived all his like in that part of the county. Unlike the majority of his class he was neither lame nor blind, yet he learned to play the Irish or Union pipes and maintained himself as a professional piper up to the time of his death.

On account of his great age and picturesque appearance he was a favorite subject for the photographers for many years, and post cards adorned with his likeness were in general circulation.

“Tom Carthy”, as he was familiarly called, made Ballybunnian his headquarters, since it became famous ‘as a summer resort. The rocky spur of land called Castle Green, always regarded as a common, was his favorite haunt until it was claimed as belonging to one of the local estates. The parish priest took issue with the claimant, and finally won the suit after spirited litigation. The old piper was restored to his accustomed stand by the victorious pastor, and assured of undis- turbed possession thereafter, a tenure which lasted for full sixty-five years.

The instrument on which he had played for generations, we are told by Mr. Richard Sullivan of Chicago, who often danced to his music, passed on his death into the possession of a man named Sullivan, of Ballyheige in the same county.

As a citizen, and as a piper, this remarkable man bore an enviable reputation. His longevity no doubt was attributable in some measure to his outdoor life, and the salubrity of the climate on the Atlantic coast.

The supremacy of John Coughlan among the few performers on the Irish or Union pipes who emigrated to Australia was undisputed from the time of his arrival in 1862 until the day of his death, April 23, 1908. He was the eldest son of Thomas Coughlan and Margaret O'Connor of Portumna, County Galway, but was born at Butler's Bridge, County Cavan, in 1837, where his parents resided temporarily. In childhood he met with an accident, which lamed him for life. This mishap practically determined his future career, and being frequently in the company of Patrick Flannery, the renowned blind piper, he acquired from the latter the hrst rudiments of piping. The Coughlan family accompanied by Flannery emigrated to America in 1845 and settled in New York City, where the subject of our sketch received instructions for a time from "Jacky" Quinn, a County Longford piper. Young Coughlan had also the advantage of precept and example from William Madden. a performer on the Union pipes almost as celebrated at Patrick Flannery, his uncle.

The elder Coughlan's ambition, stimulated probably by John's predilection and progress, led to the latter's transfer to Roxbury, Massachusetts, where he attended school and lived with "Ned" White, "The Dandy Piper," who took charge of his musical education in the evenings and made a finished piper of him. In 1835, when but eighteen years old, young Coughlan accompanied William Madden to Ireland and toured the country with him for two years before returning to New York.

Prompted no doubt by parental pride, the father induced Michael Egan, the famous piper and pipe maker of Liverpool, England, to come to New York and live with him. After practicing with Egan for some time and becoming possessed of two splendid sets of Union pipes specially made for hini by the latter. young Coughlan in his twenty-third year started out as an independent piper. His first public appearance was at Tremont Temple, Boston, in 1859, at which he was assisted by his friend Williain Madden. From that forth for some years he filled engagements all over the United States, traveling as far south as Charlestown, South Carolina, and even crossing the continent to San Francisco on the Pacific coast.

Conceiving that the disturbed condition of public sentiment arising from the Civil War was unfavorable to his prospects in America, he took passage with some members of the family for Melbourne, Australia, in June, 1862.

It may be said, however, that the abundance of money in circulation during the continuance of the war contributed not a little to the prosperity of the pipers who remained.

Coughlan was warmly received by his countrymen at Melbourne, and he played for a time at the rooms connected with Pat Hannan's Galway Club Hotel, now the site of the General Postoffice, and later at Dan Moloney's Exford Hotel in Russell Street, both places being popular resorts of young Irishmen who had preserved an enduring love for the music and dances of their native land. The migration of his sons was no part of their father's ambition, and so keen was his disappointment at the miscarriage of his cherished plans, according to his friend Nicholas Burke, that he returned to his native land and bought a farm a few miles distant from the City of Galway.

Ever in pursuit of the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, the report of rich gold discoveries on the west coast of New Zealand lured the versatile but unstable Coughlan to the land of the Maories. After wandering from camp to camp with his wonderful music he engaged in the hotel business at Canary, conducted dancing rooms of his own at Charleston and Dunedin successively, but returned to Melbourne in 1883, where he was made the beneneiary of several complimentary concerts.

Never

content, seldom satisfied, this really excellent piper transferred

his talents to Sydney in 1884, in which city and its surroundings he

played for a number of years. He appeared in Her Majesty's Theatre in

"Arrah-na-Pogue," in 1901, and later in the opera, "The

Emerald Isle."

"The frail old man," writes Morgan P. Jageurs in The Advocate, "looked quite a pathetic little figure in his velveteen kniekers and long stockings, as he limped to his seat on the stage. Once seated, the attention of his audience became riveted on his pipes. Plaintive, haunting melodies followed one another with indescribable sweetness until the theatre became as silent as a mortuary, When hey! a turn of the wrist broke the stillness with the merry nine-eight hop jig of `The Rocky Road to Dublin.' Double jigs, hornpipes and reels followed in quick succession and added to the gaiety. It was impossible to keep one's feet still. Like the Pied Piper of Hamelin, he controlled his audience at will, but never satisfied them. Their demand was for more, more-and still more." Much of the following its in Mr. Jageurs' language:

His goltraighe, or war tunes, such as "Brian Boru's March," "O'Donnell Abu" "Lord Hardwick's" "Napoleon's" "Captain Taylor's" and other military marches, were played with great spirit. The more uncommon marches of "Alastrum McDonnell" and "Feach Mac Hugh O'Byrne" were, however, not in his repertoire.

His merry reels were his best effort. Few pipers, fiddle or flute players could equal him in that class of dance music. His playing of "Miss Gunning's Reel," in particular, was something to remember, and worthy of that beautiful lady herself. Other good reels he rendered well were "The Bright Star of Munster," "Lord Gordons Reel," "Bonny Kate" "The Bucks of Oraninore," and "Erin's Hope."

Who, too, could resist his inspiriting jigs, notably "The Yellow Wattle," "The Black Rogue," and "Paudheen O,Rafferty'"? His daughter Lizzie was famed for her "American Sand Jig," which she danced to her father's piping. The air and dance were acquired from the late Tom Peel (or Radley), a clever Irish-American dancer, resident in Melbourne, who was also an excellent Irish reel exponent.

Amongst the many other frolicsome tunes played by Coughlan were a few of those irregular ones associated with figure or long set dances. He played the "Blackbird," "The Job of Journey Work," "The Suisheen Bawn," "Rodney's Glory," and "The Garden of Daisies." These were danced to Coughlan's music by noted old-time Melbourne dancers, particularly the late Denis Lyhane (who was accidentally drowned in New Zealand), Edward Tobin, J. Fitzgerald, Tom Hartnett and John Daly. The last-named is the sole survivor of this group of really line Irish long set dancers.