CHAPTER XXII

IRISH PIPERS OF DISTINCTION LIVING IN THE EARLY YEARS OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

ALTHOUGH our kinsmen of Caledonia have at all times cherished the traditions and customs of their race and clans, and possess reliable records of all their famous musicians-harpers, pipers, and fiddlers-the Irish, no less patriotic and tenacious of their national ideals, have been woefully negligent in that respect.

Since Giraldus Cambrensis, late in the twelfth century, wrote his panegyric on the harpers of Ireland, proclaiming them to be “beyond all comparison superior” to those of any nation he had seen, much of what little we know of that class of minstrels was derived from Arthur O’Neill, the celebrated blind harper of Tyrone, whose reminiscences were first given publicity by Edward Bunting in the year 1840.

The Union pipers were, however, closer to the hearts of the people and quite as famous in their line as the glorified harpers, passed away on the current of time, as unnoticed by the journalists and biographers as floating chips on the Shannon’s waters on the way to the sea. An awakened interest in the subject brings us to a realization of what we have irretrievably lost, and the meagre mention of the few notables immortalized by Grattan Flood in The Story of the Bagpipe, instead of satisfying our longing, serves but to emphasize the national delinquency.

To do partial though tardy justice to a worthy and for a time numerous class of typically Irish minstrels, would indeed be a labor of love, but at this late day, where is information to be obtained concerning the great Irish musicians and composers who nourished since the middle of the eighteenth century? Stories more legendary than reliable were to be picked up here and there, while an occasional nugget of authentic biography would prove invaluable in piecing out an otherwise disjointed story.

Years of unremitting inquiry resulted in but a tithe of the material one would reasonably expect to accumulate on this subject. In fact the gleanings were so disappointingly incomplete that this work may never have been undertaken but for the fortuitous discovery in Brooklyn, New York, of Mr. Nicholas Burke who knew and remembered the Irish pipers of his generation as well as Arthur O’Neill knew the harpers of his day.

A glance at his picture will show that he had attained the patriarchal age, and being a music lover and musician, hospitable and helpful to those of similar tastes. Every piper and fiddler of prominence who crossed the Atlantic since the middle of the nineteenth century made his acquaintance.

On learning the nature of the purpose in view, Mr. Burke obligingly “took his pen in hand” and wrote out pages upon pages of interesting memoirs dealing with nearly a score of pipers about whom we knew practically nothing, besides giving supplementary information concerning many others already on our list. In fact Mr. Burke may aptly be termed the Plutarch of the pipers.

Born in the parish of Annaghdown, on the banks of Lough Corrib, County Galway, in 1837, he emigrated to America in early manhood. From his trade as carpenter he developed into a skilful draughtsman, and eventually became a successful and prosperous builder. Like many others of his countrymen, from being an excellent performer on the flute, he took to playing the Union pipes, on which he also became proficient, but be it remembered that Nicholas Burke played only for his own pleasure or the entertainment of his friends, and invariably in his own home. In Ireland he would be called a “gentleman piper.”

His instrument, it will be observed, is of the most elaborate pattern, with a chanter of fine-grained ivory instead of wood. As Taylor, the maker of this type of Irish bagpipes, has joined the “silent majority” some years ago, and left no successor, the picture may be regarded as one possessing no little historical importance. Though in his seventy-fifth year, Mr. Burke’s memory is singularly retentive and clear and he possesses in an eminent degree the rare faculty of imparting desired information in a manner both concise and complete.

Crowned with a snow-white fringe of once luxuriant hair, through which his well-developed bump of self-esteem invites attention, and with a patriarchal beard of the same hue adorning his florid and expressive countenance, no one could more fittingly typify the dignified bard of ancient Erin in this generation than John K. Beatty, the nonogenarian dean of the Chicago pipers.

Though enfeebled by age and no longer able to play in the manner described in Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby, no tastier, livelier, jollier young man ever left the parish of Drumrany, Ballymore, in the county of Westmeath, than “Johnny” Beatty.

As jig and reel dancer he was equal to the best, and though not a musician in his youth his lilting was simply incomparable; his inconceivable combination of syllabic staccato accurately expressing every tone and shading of the most complex tune.

About eighteen years old when he landed at Brooklyn, New York, in 1839, he took to the trade of bricklaying for some years. In 1860 we find he was a member of the Illinois militia, and on the breaking out of the Civil War was actively engaged in the commissary department.

About this time Mr. Beatty commenced his musical studies under the instruction of the veteran piper James Quinn, a sketch of whose life will be found in the preceding chapter. A good set of Egan pipes which he owned were laid aside after “Billy” Taylor of Philadelphia had developed a more powerful instrument. To Mr. Beatty Dame Fortune proved tickle, yet the failure of his enterprises never chilled the warm glow of his optimism and good nature. As the sun shines behind the darkest cloud, so was ultimate prosperity in store for the genial minstrel. With the first returns from a lucrative position, a carte blanche order for a new set of pipes was given Mr. Taylor, and it was on this triumph of the great pipermaker’s art that John K. Beatty so distinguished himself.

So supreme was he at lilting that on hearing him vocalize a tune in that way, the renowned Taylor said: “Ah, Mr. Beatty, if you could only play it that way you’d be a wonder.” But he cou1dn’t. Neither could anyone else, for such rhythmic staccato was beyond their powers of execution.

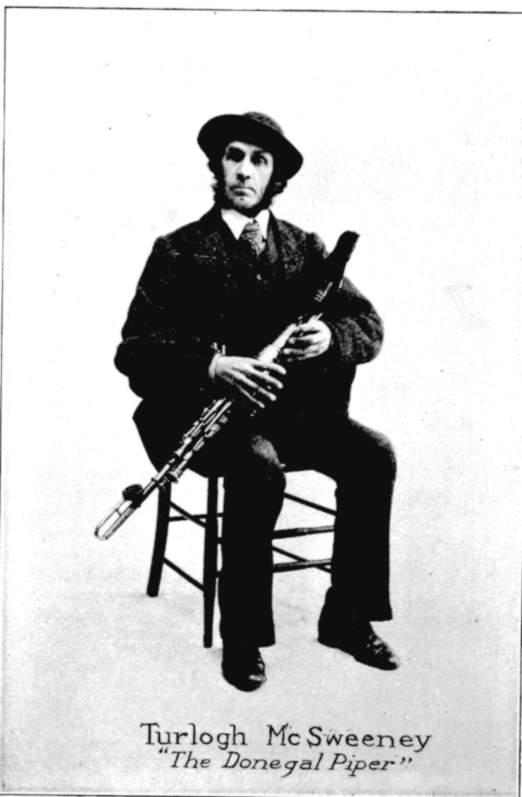

Mr. Beatty’s headlong execution on his superb set of pipes was as much of a surprise to Turlogh McSweeney, the “Donegal Piper,” as was his lilting. After watching his acrobatic performance on the huge instrument for a time, McSweeney remarked quizzically: “Begor, Mr. Beatty, you have a great shower of fingers.” And so he had.

In the exuberance of his spirits and anxiety to impress his audience with a due sense of his superlative execution, he not infrequently left much to be desired in the way of rhythmic precision, it must be confessed; and if the drones and regulators after a round or two of such strenuosity insisted on disagreeing with the chanter, it must not be regarded as a reflection on the maker, or the conduct of the instrument under milder treatment.

Like a true bard he composed and sang his own songs, mainly on topical subjects, and had his practice on the pipes been commenced in his youth instead of his manhood, the true spirit of the minstrel so dominant in his character would doubtless have gained him more enduring fame.

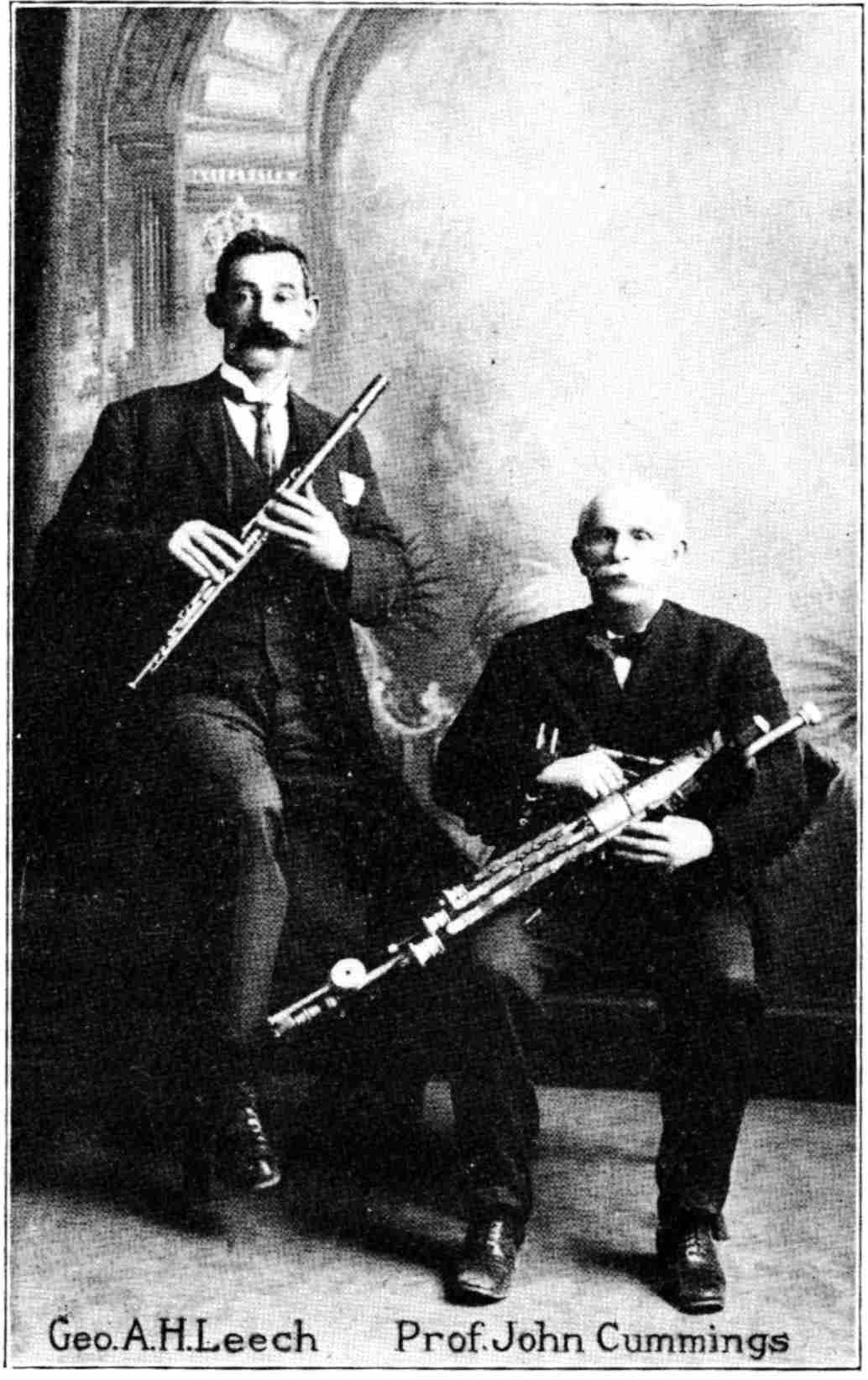

The ablest and most distinguished looking of the capable Irish pipers brought to light since the inception of the Gaelic Revival is the octogenarian Prof. John Cummings of San Francisco, California, whose likeness with that of his friend, Mr. George A. M. Leech, graces the opposite page.

In execution and versatility he is classed by competent authorities with “Patsy” Touhey and “Barney” Delaney. In this generation no greater compliment could be paid him. As one of them put it: “If not as light-fingered as Touhey now, it is safe to say that Touhey won’t play as well as Mr. Cummings at the age of eighty-four years.”

This “grand old man” was born at Athenry, County Galway, in 1828, and was taught by his father, Patrick Cummings, to whom quite a few pipers owe their early musical training. It appears that Prof. Cummings ancestors kept a college for pipers at or near Athenry for generations, the name in those days being Cummins.

Before coining to America in 1892 John Cummings had lived in England for forty years. Though an accomplished piper he was not a professional one. While in Liverpool he worked for builders, and later in the city of London he had much to do with the handling and care of horses. Only when thrown into the company of people whose tastes were similar to his own, did he indulge in his passion for music, but his most enjoyable experience was the acquaintance and companionship of Michael Egan, the famous piper and pipemaker of Liverpool, about 1850.

Amiable as he is venerable, this patriarchal minstrel fittingly typifies the bards of old in the heyday of Ireland’s glory, but fate decreed his birth a thousand years too late. In these degenerate days pipe music falls on callous ears. The German accordeon or melodeon has supplanted the Union pipes and fiddle in the land of the Gael, for the “sets” which may be extracted from the foreign instrument are more “polite” than the jig, reel, and hornpipe of our ancestors. And besides it never gets out of tune, and anyone can bring music out of it.

Had John Cummings been a contemporary of Crampton and Courtney, his name like theirs would have found a place in literature.

It is only within a year or so that his existence and phenomenal musical ability were incidentally disclosed at the Golden Gate, and now that he has reached the eighty-fourth milestone on the way to eternity the incubus of age has begun to dim the eyes, unsteady the nerves, and blight the faculties of one of Erin’s most talented yet neglected sons.

Mr. Leech, to whose zeal and devotion in the cause of Irish music we are under many obligations, induced Prof. Cummings to pose for the picture which, let us hope, will contribute something to the perpetuation of a worthy man’s name and fame.

Even at his advanced age, when he hears an old tune, or a new one for that matter which captivates his fancy, his spirit revives like an old warhorse at the sound of the bugle, and buckling on his beloved instrument, he strikes up the tune in such a masterly way, with graces and curls, as to put those who inspired him entirely in the shade. When in the humor at the social gatherings of Irish musicians at the home of his daughter, Mrs. Hogan, with whom he lives, Mr. Cummings would roll off a score of reels, that none of his audience “ever heard before or since,” as Mr. Leech expresses it.

“One night I played ‘The Raveled Hank of Yarn,’” the latter writes, “and the old man shook his head reminiscently, remarking, ‘I had forgotten that tune and didn’t play it for forty years.’ Gradually the smile came over his face, and he commenced to pump the bag, and out came the tune, but with such grace notes, embellishments, and variations, that I stood aghast, enraptured by the soul of music which brought me back to the time when Erin was melodious with our own dear strains.”

Among his father’s pupils were Michael Kenny, a good Irish piper who made some pretention to original composition, and “Patsy” Mullin, who also won distinction as a performer on the Union pipes. Another was Michael Twohill or Touhey, who Prof. Cummings believes was the grandfather of “Patsy” Touhey, the celebrated Irish-American piper and comedian-the best known of living performers on the Union pipes in this generation.

Of the two noted performers on the Union pipes still surviving in London and representing a once numerous fraternity, Daniel O’Mahony, whose stage name is “Michael O’Hara,” is regarded by Prof. P. D. Reidy as being in the same class as Thomas O’Hannigan, of an earlier generation, who played before royalty.

O’Mahony was born at Bermondsey, London, England, in 1837, and was taught music by his father, a native of Cork. In rendering dance music his rhythm and execution were faultless, and it was a rare treat for admirers of such spirited melodies to hear O’Mahony and William O’Kelly, another expert on the pipes, play in concert. The latter fell from grace many years ago but managed to reach Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, by working his passage.

So moribund is Irish sentiment as far as the old music is concerned, coupled With the lack of suitable equipments for his instrument, that the famous old minstrel confines his execution to the chanter alone in late years.

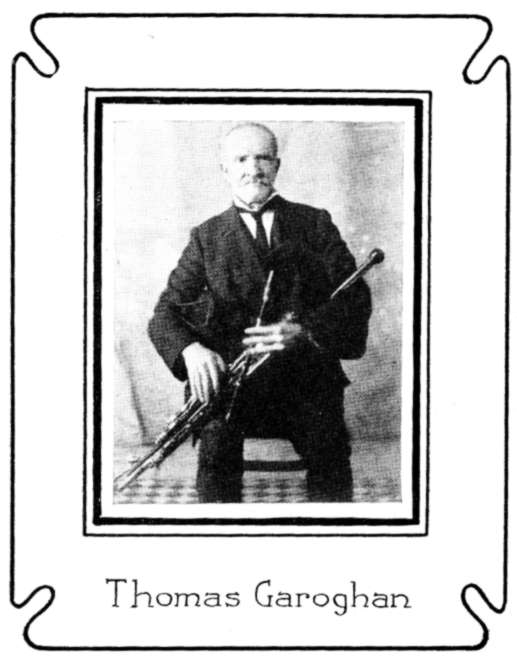

One of the pleasant surprises which conduced to render the Oireachtas of 1912 particularly interesting and enjoyable, was the introduction of Thomas Garoghan, the London piper, to a Dublin audience. He played on a full set of boxwood pipes, and according to one account, the performance was “splendid and refined, but the tone of his instrument was too weak to be effective in a large concert hall.” He did not have his pipes with him at the little assembly at Groome’s hotel, but on the stage of the Rotunda each evening his music was much admired, and by uttering intelligibly on the chanter, “Polly put the kettle on,” the unique trick aroused the audience to enthusiasm.

“Prof. Garoghan,” as he prefers to be called, was born in Coventry, Warwickshire, England, in 1845, his parents being natives of County Mayo, Ireland. He learned to play the Union pipes from James O’Rourke of Birmingham and Michael McGlynn of Aughamore, who were well known in the midland counties of England half a century ago.

Piper Garoghan is a fluent Irish speaker. Having acquired the language from his parents, and the Irishmen who come in large numbers every year to reap the English harvest; but the event which was the crowning glory of his life was his eight months’ engagement with the “Shemus O’Brien” opera company at His Majesty’s Theatre, London, some years ago. Always spry and active, he has kept the Irish pipes to the front for forty-live years, and in a country in which there was said to he an Irish piper for every day in the year less than two generations ago, he is now one of the very few remaining. He is back again in London, for after indulging a very natural desire to visit the land of his forefathers, he finds that, after all, “There’s no place like home.”

At the annual picnic of the Highland Pipers’ Band of Chicago in 1912, the present writer complimented a member of it for his proficiency. “The Irish bagpipe is what I would like to play,” he answered, pointing to Adam Tobin, who, seated under the shade of a convenient tree, was manipulating such an instrument. We inquired where he had heard an Irish piper before, and learned that he had often listened with pleasure to an Irish piper of fine ability at Jamaica bridge, Glasgow. His name he did not know, but the location mentioned furnished a clew which, through the courtesy of Inspector James R. Motion of the Glasgow department of police, led to the information desired.

In London there are still surviving two capable performers on the Irish or Union pipes-Daniel O’Mahony and Thomas Garoghan-but the death of Peter Kelly, the man alluded to by McPhail on the first day of April, 1910, at the age of seventy-three, ends the race of Irish pipers in Scotland.

Peter Kelly was horn in the historic City of Galway, and was stricken with blindness when but a few months old. Arriving at a suitable age, his patents arranged to have him taught by the celebrated Martin O’Reilly. With whom they were well acquainted. He proved to be an apt pupil, and a set of pipes then about forty years old were with the aid of friends procured for him at Liverpool, and it was this set he played on to within a few days of his death.

He was about thirty years of age when he went to Glasgow on a visit with a fiddler named John Crockwell, and finding that thriving city to his liking he made it his permanent home. His widow and three of his nine Children survive him.

In the early years of his married life, the Irish bagpipes being comparatively new to Glasgow, Kelly was quite prosperous, and it was no unusual thing for him to take in one pound ten shillings or even two pounds on a Saturday night alone, but of late years and up to the time of his death, his receipts diminished to not over one-fourth of those amounts. `

Occasionally he would take a trip to Edinburgh, and during the summer season to Portobello, and reap a better reward than when at home. About thirty years ago he played at one of the theatres in Edinburgh at a benefit given to a then well-known Irish comedian named “Pat” Feeney.

At the invitation of Dr. Boyd of Belfast, Kelly went to that city in 1898 to play at a competition, and notwithstanding his being awarded but third prize by the local judges, he was honored by being selected by the Lord Mayor to play at a reception given at the city hall that same evening, a circumstance which goes to show that his performance was appreciated by the authorities.

Shortly after this event a similar competition was arranged to take place in the National Halls, Glasgow. Only three players came forward, these being Kelly and two farmers-a father and son, natives of Ireland-from a remote part of Scotland. Kelly was adjudged the winner without hesitation.

In Glasgow his services were in great demand at gatherings of the Ancient Order of Hibernians; United Irish League, etc.; and his proficiency and popularity on such occasions always insured him a warm welcome and a good fee.

This ideal old minstrel was a well-known figure for many years in the vicinity of the Jamaica and Albert bridges, and opposite the Queen Street Station, but instead of sitting down while playing he stood upright, resting his right leg above the knee on a short crotched stick so as to manipulate his instrument successfully. He had the reputation of being a particularly skilful and sweet player, and Mr. Henderson, the famous bagpipe maker who made his reeds, speaks in very high terms of his capabilities as a musician. Kelly played all his music by ear, and so quick was he in picking up a tune, that if he heard it played, sung, or whistled once, he could repeat it on the pipes without making a mistake. His favorite melodies were “The Coolin” and “The Blackbird.”

Very often he was accompanied by another blind man named Smith, who played the flute, and the two were looked upon as inseparable cronies, and both were equally fond of their pint of porter, though by no means drunkards. Kelly was at his usual stand on the Albert bridge on the Saturday evening preceding his death from pneumonia four days later.

Dire want drove his widow to a pawnshop with the pipes shortly after, and the generous ( ?) pawnbroker said, had not the chanter been worn nearly through by the finger marks he could afford to have given much more than the ten shillings he allowed her.

Thomas Rudd of Clone, near Ferns, County Wexford-a gentleman farmer whose name comes down to us as a piper of no inferior merit- was an early contemporary and friend of Mr. Rowsome’s. He used to enliven the harvest-work of his employes by bringing his pipes to the field and playing to them the popular melodies which they loved and were accustomed to hear, and which in those days when the peasantry had few comforts and no luxuries, constituted one of the greatest joys of their existence.

Mr. Rudd was one of the leading farmers of Wexford in his time. As none of his family inherited his musical proclivities, his instruments, of which he possessed more than one valuable set, passed after his death, which occured fifty years ago, into the hands of the late John Cash.

A defective chanter which Mr. Rudd owned, after undergoing an overhauling at the hands of his friend Mr. Rowsome, was declared to be the “truest he ever handled.”

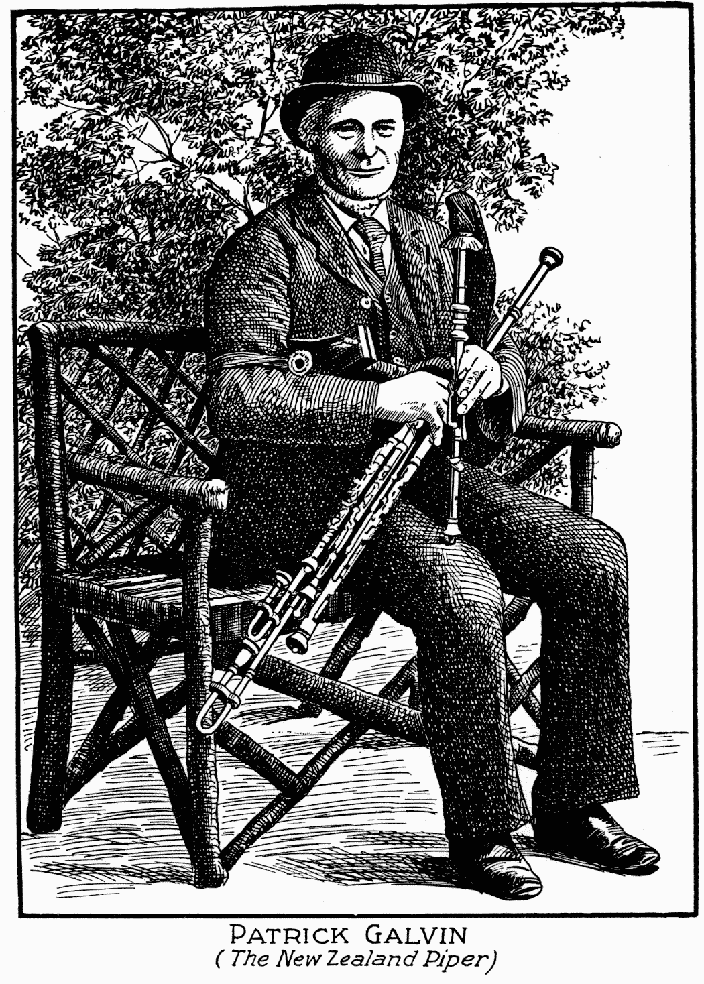

As widely dispersed all over the English-speaking world as the most adventurous of their countrymen, were the tuneful Irish pipers, although it is by the merest chance that we learn of their existence on the other side of the globe.

Had not Mr. Galvin returned from Shingle Creek Hotel, Otago, New Zealand, to visit the scenes of his childhood at Corofin, County Clare, at the end of the century, after forty years’ exile, his picture would not have been included in our gallery of famous Irish pipers.

He looks the part in every sense of the word though out of practice for many years. He visited the Cork Pipers’ Club during his stay, and “Bob” Thompson supplied reeds and guills for a new set of pipes which Mr. Galvin had purchased from C. Butler & Sons. Returning to New Zealand, he took with him a step dancer to revive the Irish pastimes at the Antipodes.

No Irish piper of ancient or modern times, unless it be “the piper who played before Moses,” has been the subject of so much publicity as McSweeney, “the Donegal Piper,” since brought to light by Mrs. Hart and installed at “Donegal Castle” on the Midway of the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893.

In the evolution of time and the decay of ancient Irish institutions during the nineteenth century, the professional piper sometimes was obliged to abandon his calling and seek a livelihood by more profitable means, and so it was with McSweeney.

On his arrival in Chicago, McSweeney found that his instrument from age and disuse was entirely unfit for the service required; and had it not been for the kind helpfulness of Sergt. James Early, it would have been scarcely possible for him to fulfil his mission.

While the “Donegal Piper” played outside the main entrance to “Donegal Castle,” “Patsy” Touhey, the great Irish-American piper, was the center of attraction within; and no two musicians on the Midway, representing their respective countries, won more attention or elicited more praise than they.

As McSweeney enjoyed the hospitality of Sergt. Early from Saturday evening until Monday morning, during his six months’ stay in Chicago, we were afforded ample opportunity to hear him at his best.

For an Irish piper, his coldness and reticence were in marked contrast with the manners of most persons of his class. This taciturnity may have been constitutional; yet who knows but it was the visible effect of maintaining the dignity befitting a distinguished piper, conscious of his descent from the chieftains of the once powerful Clan MacSuibhne of Tir-Conaill. Be that as it may, he rarely relaxed his reserve. With his host and benefactor, Sergt. Early, and with Mr. Gillan, a great admirer of his music, he was more communicative and almost cordial.

It was while in one of his gracious moods that he confided to them how he same to be such a great piper. In his young days McSweeney was no musical prodigy, as one may surmise from his subsequent reputation. In fact, he was not much of a player at all, according to his own account, though having the advantage of heredity and example; for his father and grandfather, particularly the latter, were fine pipers in their day. “There was no music in me,” is the way he tells of his lack of talent, but he was anxious to learn and be a credit to his name and ancestry.

Despairing of other means of attaining success, it occurred to him to make an appeal to the fairies on the rath of Gaeth-Doir on the hilltop, half a mile away. One moonlight night, he plucked up courage, and with his pipes buckled on all ready for playing, he made his way up along the “boreen” and across the fields and timidly entered the fort. But perhaps the reader would prefer to read the story in his own words:

“Well, as I was saying, when I got to the center of the Plasog, as near as I could tell, you may be sure I wasn’t any too comfortable. Anyhow, I addressed myself to the king of the fairies, saying: ‘I’m Turlogh McSweeney, the piper of Gwedore, and I hope you will pardon my boldness for coming to ask your majesty to play a ‘chune’ on the pipes for me, and I’ll return the compliment and play for you.’ Yerra, man, like a shot out of a gun, the words were hardly out of my mouth when the grandest music of many pipers, let alone one, playing all together, filled my ears; and that wasn’t all, for lo and behold you, what should I see but scores of little fairies or luricauns, wearing red caps, neatly footing it, as if for a wager. Believe me, I was so overcome with fright at such a strange and unexpected sight that I ran for the bare life, my pipes hanging to me and dropping off piece and joint along the way; and by the time I reached home, the dickens a bit of my whole set of pipes was left to me but the bellows and bag, and they couldn’t let go, as they were strapped round my waist.

“Picture to yourselves the kind of a night I spent after what happened. Anyway, by sun-up in the morning I ventured out and started to try and pick up the disjointed sections of my pipes, as I knew well enough the route I ran. My luck relieved my misgivings when I found the last missing part, which had dropped off at the very entrance to the rath or fort when I ran away.

“I lost no time in putting the now complete instrument in order, and to keep my word and fulfil my promise made to the king of the fairies the night before, I struck up ‘The Wild Irishman,’ my favorite reel. Words can’t express my astonishment and delight when I found I could play as well as the best of them. And that, gentlemen, is how I came to be the best Union piper of my day in that part of the country.”

“Many years after that, when I was living alone in the little cabin after my mother died-God rest her soul-there came to the door in the dusk of the even- ing a stranger and nothing less than a piper, by the way, who with a ‘God save all here,’ introduced himself as was customary. I invited him in, of coorse, and after making himself at aise he says, ‘Would you like to hear a ‘chune’ on the pipes?’ ‘I would that,’ said I, for you know a piper and his music are always welcome in an Irish home. Taking his pipes out of the bag, he laid them on the bed beside him, and what do you think but without anyone laying a finger on them, they-struck up ‘Toss the Feathers’ in a way that would make a cripple get up and dance. After a while, when they stopped, he says, `Will you play a `chune’ for me now?” I said I would and welcome, pulling the blanket off my pipes that were hid under the bedclothes, to keep the reeds from drying out. ‘Give us Seaghan ua Duibhir an Gleanna’ (Shaun O’Dheir an Glanna), says I to the pipes, and when they commenced to play, the mysterious stranger, who no doubt was a fairy, remarked, ‘Ah! Mac, I see you are one of us.’ With that, both sets of pipes played half a dozen ‘chunes’ together. When they had enough of it, the fairy picked up his pipes and put them in the green bag again. If I had any doubts about him before, I had none at all when he said familiarly, ‘Mac, I’m delighted with my visit here this evening, and as I have several other calls to make I’ll have to be after bidding you good night, but if I should happen to be passing this way again, I’ll be sure to drop in.’

“We must be always careful to not offend the ‘good people,’ but as I traveled around through the Northern Counties a great deal after that, and even into Scotland, of course he couldn’t blame me it I wasn’t at home to entertain him if he happened to call during my absence..”

On another occasion McSweeney was the centre of attraction at a house party gotten up in his honor by Mr. John Gillan. Naturally all present were musicians or music-lovers, and taking into consideration the lavish hospitality of an Irish host, it occasioned no surprise when. Under the mollifying influence of a few tumblers of screeching hot punch, “the Donegal Piper” relaxed his customary reserve and became almost sociable.

When he realized that “Billy” McCormick, a local piper present, was an admirer instead of a rival, and that he could converse with him in his native Irish, he “took” to him at once and invited him out during a lull in the festivities. Instead of speaking to McCormick, however, his mysterious mutterings seemed to be addressed to someone else not visible in the darkness. McCormick began to feel uneasy, and his dismay was not lessened when McSweeney abruptly asked him, “Would you like to have the scum lifted from your eyes? If you do, I’ll show you something,” at the same time slipping him an old country jobbers penny. Keenly alive to the insidious liberality of the dreaded recruiting sergeant, and the fatal consequences of accepting gifts from the fairies, McCormick did not wait to answer, but headed for home as fast as his legs could carry him, and without observing the merest formalities of leave-taking. Convinced that “the Donegal Piper”, was either a fairy himself, or their agent, McCormick carefully avoided meeting him thereafter.

‘Twas nearly midnight when that ardent music-lover Mr. Gillan, the genial host, called for “Cherish the Ladies,” his favorite jig. When the star of the evening, McSweeney, had played it to the satisfaction of all present, he deliberately lit his pipe and announced: “Now, Mr. Gillan, I’ve been playing for you all night, and I think it is about time I should play something for ourselves.” With that he took the whiskey jug, yet far from being empty, opened the backdoor, and peering into the backyard, said in a familiar tone, as if inviting intimate friends: “Boys, everybody come here and help yourselves.” Suiting the action to the words, he deposited the precious jug on the platform, just outside the door, where it is presumed the fairy host regaled themselves to their hearts’ content. From that time, and until near daylight, McSweeney, who had changed from the parlor to a seat near the kitchen door, played for the fairies without stopping or uttering a word, and you may say ‘twas he had the bag full of tunes. Mr. Gillan, who was listening in rapt attention all the time, and ought to know, being an excellent judge of music, assures us that the music Mac played for the fairies’ entertainment was much superior to his performance in the parlor in the early part of the night.

At what hour the invisible audience departed, we are unable to say, but when the good lady of the house came down stairs in the morning, the piper lay on the kitchen floor, pipes and all, with his head projecting half way under the stove, while Mr. Gillan himself was sound asleep in an easy chair. The jug was empty and as the host “wasn’t taking anything,” who could have drained it if the fairies hadn’t?

Professional jealousy, especially among musicians, that bane of fellowship and concerted effort, is sure to find a vent. And although Turlogh McSweeney betrayed no evidence of membership in the “knockers’ club,” that didn’t save him from being the subject of a poem (God save the mark), calculated to disparage his musical pretentions. It emanated from the fertile brain of the versatile John K. Beatty, who, to insure its preservation, sang it haltingly into an Edison phonograph to the tune of “Fagamaoid sud mar ata se.” As a sample of what a poetical piper can perpetrate when he gets his muse in motion, a few verses are here reproduced. With apologies to the reader:

The Donegal Piper

Ye sons of Apollo come listen to me.

And a comical story I’ll tell unto ye;

Of a musical janius that came brass the sea,

To represent all Irish pipers.

When he came from New York to the great World’s Fair,

He met champion Murphy of the auburn hair,

And big blowhard Ennis from the County Kildare,

Who call themselves all Irish pipers.

When he got his engagement, late in the spring,

He took his seat with an air that would rival a king.

Some friends went to see him and presents did bring,

And called him “The Donegal Piper.”

He had but one reel called “Up the Broomstick,”

And all other reels he would pitch to “Ould Nick”:

The way that he played it was but an old trick,

For that man called “The Donegal Piper.”

He played every day from the time he got there,

And the Touheys and Flahertys came in for their share,

Such trios as they, sure would make a man swear,

That e’er heard a genuine piper.

When his flat-throated chanter and pipes gave a squall

They were like a screech owl or a whipperwill’s call!

Why Mozart or Beethoven wasn’t in it at all

With this man called “The Donegal Piper.”

I’ve heard all the pipers from ‘round Skibbereen,

And from Ballinafad up to Sweet College Green;

Arrah! Such a mimic on Irish was never yet seen

As this man called “The Donegal Piper.”

But now he is gone and our spirits are low,

And I say God be with him, Go deo’s go deo, (For ever and ever.)

Since Ireland was scourged by that villain Strongbow,

You never have heard such a piper.

Search Ireland all o’er from seashore to seashore,

From the cliffs of Cape Clear to the rath of Gwedore,

And you’ll ne’er meet man such a musical bore

As the one called “The Donegal Piper.”

And so ends the story of the “Donegal Piper,” partly as told by himself in all seriousness to men not much his junior in years. For obvious reasons such tales are never debatable, yet those who came in contact with the taciturn minstrel felt that there was something strange, inscrutable, and even uncanny, in his whole demeanor.

Wonderfully even and correct was his rendition of Irish airs, and his system- atic manipulation of the regulators or concords in difficult and varied pieces plainly demonstrated that his instructor had an apt pupil. And still, withal, the coldness of his character was reflected in his music. Faultless in time as the tones of a hand organ, the spirit of the Irish tune seemed lacking-that spirit which, even at the hands of a less capable performer, invigorates our system and impels us to dance or beat time to the rhythm.

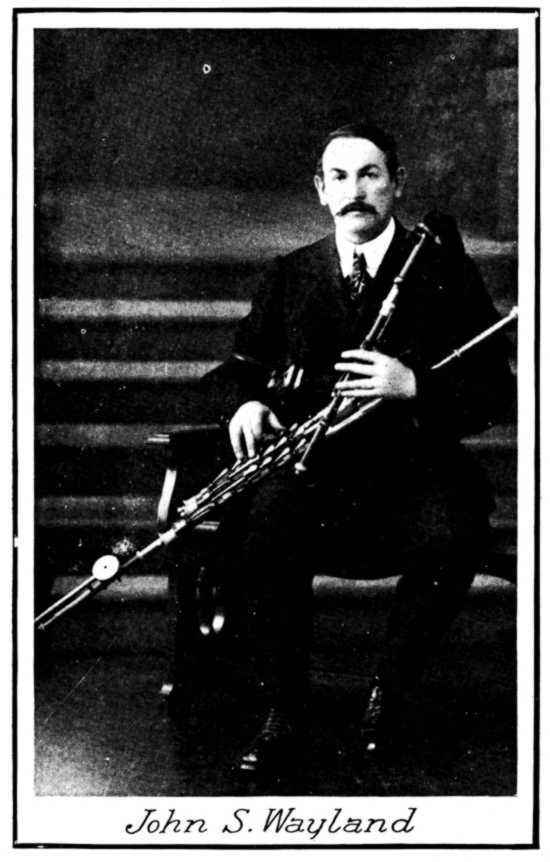

To an issue of The Christian Age in 1909, kindly sent by Mr. J. S. Wayland we are indebted for the following:

“In the varying fortunes of its people, the history of few countries presents more striking examples than that of Ireland. The many and fierce internecine wars with which Ireland was distracted in her early days, followed by the Anglo- Norman conquest of the country in the twelfth century, has tended to bring about a state of affairs, by which at the present time, some families who formerly ranked among the highest in the land, are now in poverty, while others have been raised from obscurity and are at present in possession of wealthy estates.

“A notable example of the reverses of fortune is afforded by the subject of this picture, in the person of Turlogh McSweeney. A reference to O’Hart’s Irish Pedigrees will show that the anecstors of this remarkable old man, born in 1829, and who has followed the occupation of professional Irish piper, were formerly princes closely connected with the royal line of Ireland. The records of his race have been so carefully preserved that his pedigree can be traced to Eremon, first king of Ireland, in the year 1690 B. C.”

Then follows a list of the names of comparatively modern ancestors, ending with Donnchad Mor (last of the MeSweeney chieftains), son of Sir Miles MeSweeney of Doe castle. No wonder his dignity and reserve were well nigh impenetrable.

In a letter to Mr. Wayland from Strabane, County Tyrone, in 1909, the writer, who chanced to meet our hero, has this to say of him: “McSweeney is a very queer old man, and will give no information about pipes or piping whatever. He still claims to have a book of instruction for the pipes, and has it for over sixty years, but would not part with it, as ‘tis the only one in existence at the present time. He has had offers for it several times, but money could not induce him to part with it. He would give no information in regard to the book, or how he got it. He would give lessons on the pipes, but would not make known the terms. He has no pupils. Neither of his two sons plays the pipes, but it is rumored that one of his five daughters could. (As she as well as the others of his children have scattered far and wide, I could not trace her.)”

In the pipers’ competition at the first Dublin Feis Ceoil in 1897, where Mr. Wayland met him, McSweeney was awarded the second prize. Robert Thompson, winner of the first prize, was similarly honored at the Belfast Feis the following year.

Being in line with the tales of fairy enchantment, his mysterious allusions to a book of “instructions” all through his career have served to make him an object of peculiar interest to people of his class everywhere. No human eye, except his own, has ever been permitted to profane this treasure by even a glance. As a concession to his benefactors before named, he presented them with a scale of the natural notes on the Irish chanter, which, upon comparison, we find is identical with that to be found in O’Farrell’s National Irish Music and reprinted in Appendix A of Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby.

It is claimed that the only copy of O’Farrell’s work in Ireland is in the library of the Dublin Museum. By way of information, it may be added that another Copy, recently procured through a London book agency, occupies an honored place in the writer’s library. Even so, the “Donegal Piper,” may well regard his treasure as priceless, cherishing, as he undoubtedly does, the hallucination that he possesses the only copy in existence of one of the rarest and most unique works ever printed on a British press.

To add to his fame, he has been immortalized by the poetess, Anna Johnston (now Mrs. Seumas McManus) in a poem bearing his name.

A health to you, Piper,

and your pipes silver-tongued, clear and sweet in their crooning.

Full of the music they gathered at morn

On your high heather hills from the lark on the wing,

From the blackbird at eve on the blossoming thorn,

From the little green linnet whose plaining they sing,

And the joy and the hope in the heart of the spring-

O Turlogh MacSweeney!

Although five more verses and a peroration follow from the same gifted pen, we must bid adieu to the “Donegal Piper,” and wish him long life in his eighty-fourth year.

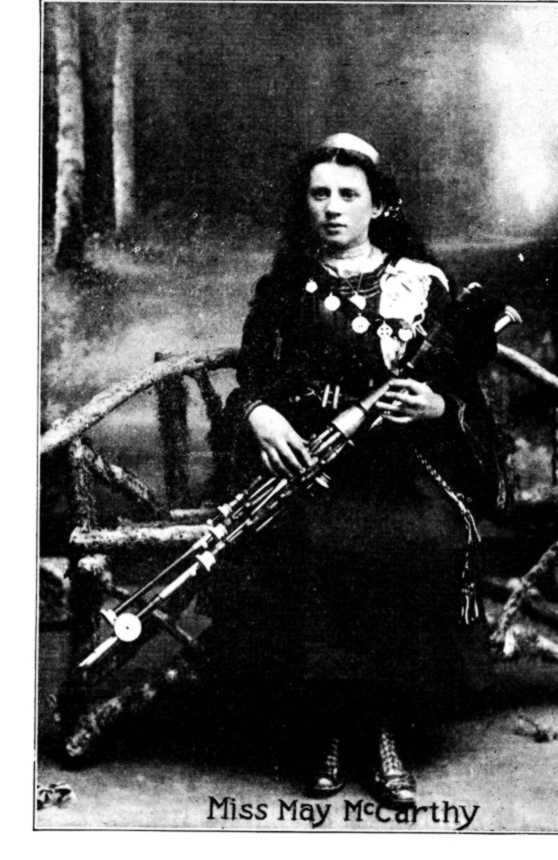

No name has appeared so frequently in the list of prize-winners at Dublin Feiseanna as that of George McCarthy. In the years 1900, 1902, 1904, and 1905 he was awarded second prize. In 1903, he was not so fortunate, getting but third prize. To crown his successes he gained first prize in 1907, and from the records it appears that in 1900 he also was awarded third prize for his collection of “Unpublished Irish Airs.”

Although the name would indicate a Munster origin, McCarthy was a native of Cavan, where generations of his forebears had lived. The McCarthy family evidently had a strong predilection for the pipes. Four brothers, including George’s father, were performers on that instrument. George being lame, became a professional piper, after some time spent under the instruction of “Billy” Taylor at Drogheda. He invariably played on a double chanter, and was in no wise niggardly in the purchase of a suitable instrument.

After his triumph in 1907 he played in the neighborhood of Blackrock, County Dublin, for some months. But eventually took refuge in the Ardee Union Workhouse, where he died in 1908, being then about sixty-five-years of age.

McCarthy’s fine silver-mounted set of pipes, made by the famous Taylor, was sold for twenty pounds to pipemaker R. L. O’Mealy of Belfast, who can appreciate their value.

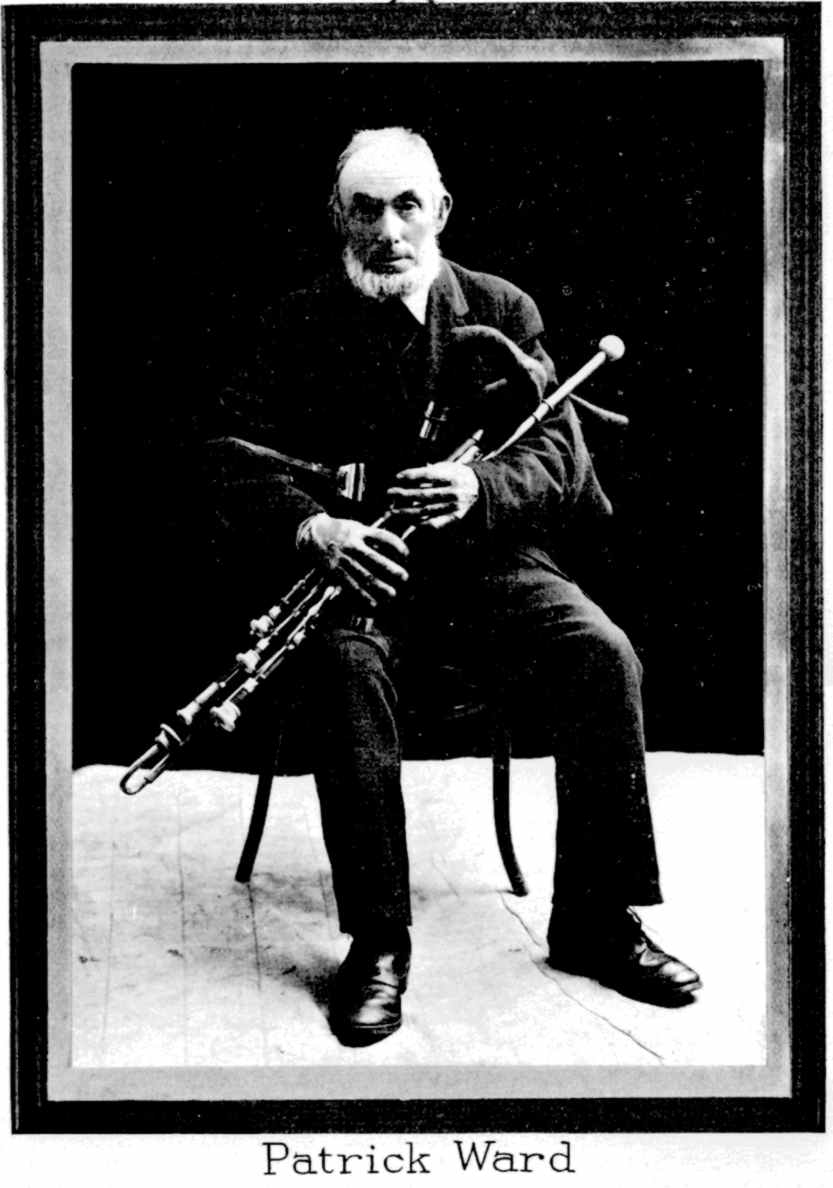

“The blind piper of Roscommon,” born in the early sixties, and brought up on the DeFreyne estates, first saw the light at Ballaghaderreen, County Mayo, a few miles from the boundary line. Being blind from childhood, he began the study of the Union pipes at an early age under the tuition of Patrick Vizard. A relative, and, like many others of his class, he was unable to procure a good instrument. So superior was his skill, however, that it made amends for that drawback, and in a short time his splendid performance attracted wide attention in that part of the country.

One day, while playing at a crossroads dance, his performance so charmed Lady DeFreyne, who happened along in her carriage, that she stopped to listen to the line music played by the blind minstrel. Drawing closer, she asked him to play a favorite Irish air. He willingly complied, and impressed her so deeply by his manner no less than by his delightful rendering of the touching melody, that she presented him with a splendid set of pipes and started him on the roam to fame.

With the new instrument his popularity increased and people came from far and near to hear him. He was in great demand throughout County Roscommon to play at weddings and other festivities.

One young man now living in Chicago, named Edward Creaghton, a prize-winner in the flute contest in the Chicago Feis of 19l2, who attended a wedding where O’Gorman played, thus describes the event: “I was delighted to get an invitation, for I was anxious to hear him play. When I got near the house, I could hear the strains of his fascinating music, and when I entered I beheld the famous blind piper mounted on a little stage in a corner of the room. His music was such as to set every foot in motion, for it seems no one could keep still. He had a fine set of pipes, which took up a lot of room, but there was melody issuing from every one of them, and the line reels which he rolled out on that evening, although years ago, are still ringing in my ears.”

O’Gorman was universally respected. Whenever any event of importance was coming off, the first thing to be done was to send after him in a side car, a conveyance in which he was taken home again when his engagement was ended. Generous and liberal with his music, he played for all who asked him; in fact, his whole soul was in the beloved instrument, which responded in seeming sympathy with his touch. In close lingering and “peppering,’ he was an expert. The first prize awarded him at the Oireachtas in 1902 was no more than his due-George McCarthy and Denis Delaney getting second and third prizes, respectively. In 1908 O’Gorman did not fare so well, being defeated for first prize by Delaney.

In the long line of immortal minstrels which Hibernia has produced. “The blind piper of Roscommon” deserves a worthy place, and the province of Connacht, in which so many of them were born, shall long cherish the name of John O’Gorman.

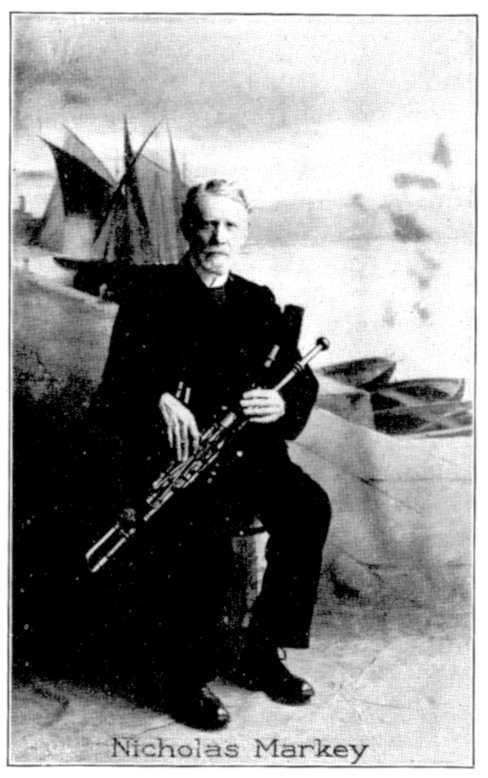

An advertisement in the Dublin press of 1910 announces that “Nicholas Markey, 45 St. Josephs Place, Nelson Street, Dublin, pupil of the celebrated “Willie” Taylor of Drogheda and Philadelphia, gives tuition on the Irish Union Bagpipes.”

For several years Mr. Markey has been instructor in the Dublin Pipers` Club, and it is said that his pupils have won distinction at the annual competitions. For obvious reasons, teachers are not inclined to take part in contests of skill, and this reluctance no doubt accounts for the absence of his name from the lists of prize winners at the annual Feiseanna, which have come to hand.

The publication of the likeness of this line type of the Irish minstrel is a source of no small pleasure to the writer, and even though we cannot subscribe to the opinion of his friend, Mr. Deegan, the honorable secretary of said club, that Mr. Markey “is the best living piper,” we can readily concede that for an Irish piper his modesty is truly refreshing. But after all what else could be expected from such a prepossessing representative of his race and profession, but the manners of a gentleman?

Another of the few surviving pipers, famous but forgotten, which the Gaelic League has resurrected, is Stephen Ruane, of Shantalla, Galway. That ardent revivalist, John S. Wayland, of the Cork Pipers’ Club, traced him up and paid him a visit at his home just outside the “City of the Tribes.” Ruane displayed wonderful execution on the chanter, but did not manipulate the regulators, possibly on account of their being not properly equipped with reeds.

Persuaded by Mr. Wayland, he attended the Dublin Feis in 1906, and was awarded the first prize, notwithstanding his long seclusion and want of practice. His fine execution on the chanter at the Feis in 1912, in which there were seventeen competitors, was remarked, but as his instrument was in wretched tune it militated against his success accordingly. Ruane, who was originally a farmer, is a very tall man of quite respectable appearance.

In early and middle life this typical amateur piper enjoyed a great local reputation in the barony of Scarawalsh, County Wexford. Far-famed as a jig player-the jig which has become unfashionable in his old days-it was no vain boast that he had a hundred of its several varieties at his finger tips. A man of untiring energy in all respects, Samuel Rowsome was an indefatigable piper. On one occasion, Mr. Whelan his friend tells us, he supplied the music unaided at a ball held at “The Harrow,” where eighty-four couples assembled, and in the words of one who was present “gave them all dancing enough.” In fact, Mr.Rowsome could “fill the house with music.” Contemporary with the late John Cash, his inborn love of the native music and talent for playing it on the Union pipes was developed under the tuition of the famous but almost forgotten minstrel, “Jemmy” Byrne, the piper of Shangarry, County Carlow.

Mr. Rowsome, who was an extensive and prosperous farmer and whose commodious dwelling typified Irish hospitality, adopted pipe playing not as a vocation but as an accessory to pleasure and recreation, for he was ever an advocate of pastimes and social intercourse.

He attended the “’patron,’ race, and fair,” and went everywhere a good piper was to be heard. Not many indeed were the wandering musicians worthy of note in that part of the country he had not come across, and few were the tunes they played that he did not memorize, if new to him, and reproduce at will.

A piper of acknowledged ability, he was no less skilful in equipping and repairing the instrument from bellows to reeds, so that we can well conceive how much in demand a man must be who combined the various endowments of Samuel Rowsome of Ballintore, whose hospitable home sheltered many a wandering minstrel in times of stress and stringency.

How could the later generations of Rowsomes escape their musical tendencies if heredity is to be considered as a factor in influencing out lives.

Mrs. Rowsome, born Mary Parslow, was not only one of the finest dancers of her day, but also an excellent violinist by all accounts, being taught by her father, William Parslow, of Ballyhaddock, a townland adjoining Ballintore. Not only that, but her brother Thomas was a piper of good local reputation. Example, heredity, and environment could hardly fail to produce conspicuous results under such circumstances.

At the patriarchal age of eighty-four, Mr. Rowsome is still living at the old homestead.

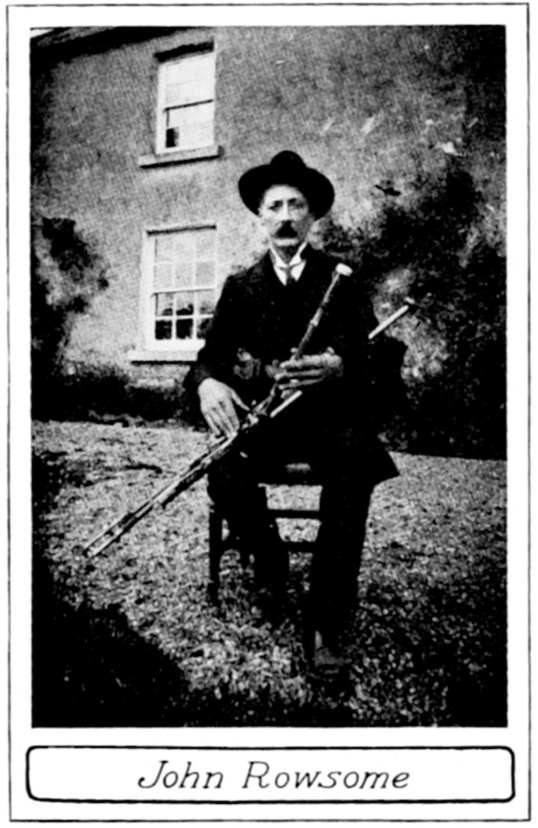

“For power of extracting a strong, voluble tone from the chanter, and imparting a beautiful expression to the music, he has few peers and certainly no superior.” Such is the language of an enthusiastic admirer in describing the accomplishments of John Rowsome, the eldest Son of Samuel Rowsome of Ballintore Ferns, County Wexford, who resides on the old homestead and is consequently unknown to fame. As Mr. Whelan is a very interesting though somewhat partial writer we will let him continue: “There are surely none more conversant with the law of modulation in music. To hear him play a great Irish reel is like listening to the warring elements of nature. The music from his chanter comes with the impetuosity of the wind, which gathers force in its gambols down the mountain side to accelerate its wild career over the plain. And anon it lingers or seems to linger, and goes on again with increased velocity. It comes in undulating waves of sound, and breaks upon the ear as the swells of the ocean break upon the beach and disperse around the feet of the spectator.

“Who that has listened to the roar of the distant cataract in the stillness of the night would fail to be impressed with a sense that a greater volume of water overleaps the rock, and plunges into the chasm below with correspondingly increasing fury at certain intervals than at others?

“Any or all of the above similes might he taken as illustrations of his music, yet they are but poorly or indifferently put, for still the music swells, breaks, leaps, curvets, sighs, murmurs, ripples, laughs, rolls, thunders, on the ear of the enraptured listener.

“The noise emitted through the chanter and from the strings of many of the swelled heads, is mete musical chatter in comparison to his playing, nor is it to be wondered at, since the musical faculty with him was inborn, and James Cash, that ‘prince of pipers,’ was through all his early years his most intimate associate, friend, and tutor.”

But coming back to earth from Patrick Whelan’s aerial flights, we hasten to inform the reader that John Rowsome, as well as his brothers Thomas and William, studied music under Herr Jacob Blowitz, a German professor, who resided in Ferns from 1878 to 1885, and became efficient performers on various orchestral instruments. John was famous on the cornet, on which he could play jigs as fluently as William could on the violin. Strange to say, heredity overcame their training under Professor Blowitz, and all three owe their present fame to their skill as performers on the Union bagpipes.

Since succeeding his father in the management of the farm, John has not played in public, nor has he continued his practice of music except in a desultory way in private. Just as he would be warming up to his work and when his audience would be anticipating a musical treat, he would strike a few chords on the regulators and put away the instrument heedless of protest or entreaty.

Nearing the half century milestone in age, he is unostentatious in the extreme, though active in all that pertains to the revival of interest in Irish music, and the art of giving it traditional expression on Ireland’s national instrument. He has furbished, repaired, renovated, and reeded more foundered sets of bagpipes, for the unskilful, than any other man in the south of Ireland.

Neither is this splendid type of the whole-souled Irishman inclined to “hide his light under a bushel,” like so many excellent pipers whom we could name.

John Rowsome sees no glory in taking his art or his tunes to the grave with him. Like so many small-bore musicians afflicted with atrophied consciences. On the contrary, to his great credit, he is teaching his art, as his generous-hearted father did before him, to all who cared to learn. Among his present pupils are his young neighbors, David and Bernard Bolger, of the manufacturing firm of “David Bolger and Sons,” and their maternal uncle, Joseph Sinnott, draper at Enniscorthy. Who is active and enthusiastic in Gaelic circles.

Wealthy, popular, and patriotic, three members of the Bolger family represented constituencies in the first election assembly which supplanted the Grand Jury system in Wexford, and it is quite within the bounds of probability that in the near future two “gentlemen pipers” of the name will succeed their honored relatives in the same capacity.

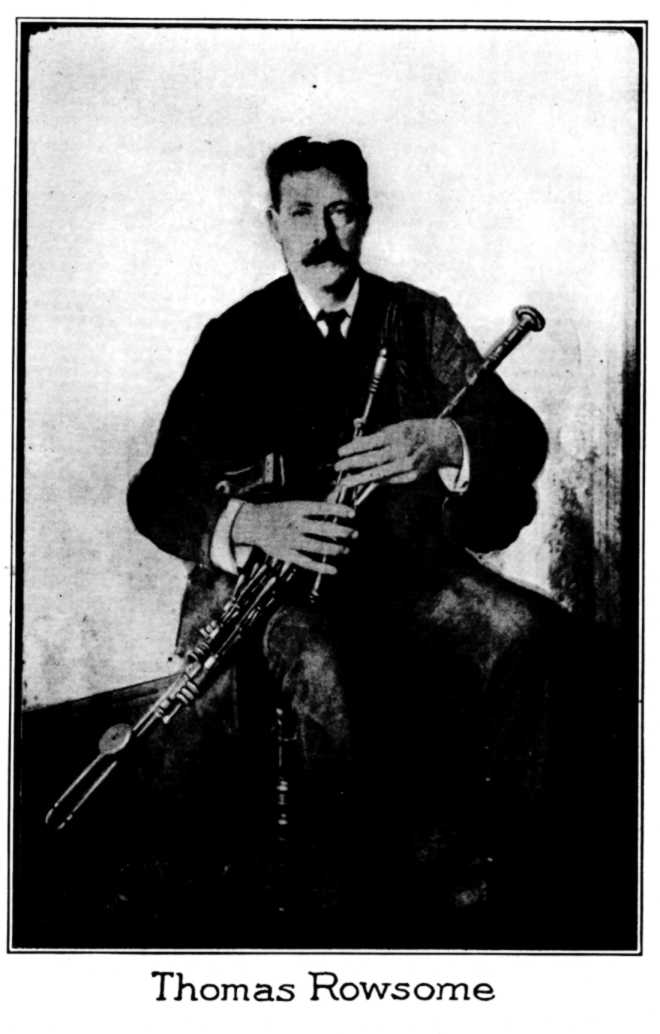

Of this member of the Rowsome family of pipers we can say nothing from personal knowledge, but we are reliably informed that Thomas Rowsome is not inferior to his brother William as a performer on the Union pipes. In fact, some are inclined to believe that, in rendering Irish airs with the manipulation of the regulators, Thomas has the advantage. At any rate it speaks well for the latter’s ability that he was awarded first prize at the Dublin Feis Ceoil competition among pipers in 1899. Winning third prize even, in 1897, when “Bob” Thompson of Cork and Turlogh McSweeney. “the Donegal piper,” were awarded first and second prizes respectively, was no small honor indeed.

From a discriminating pen we learn that “Tom” Rowsome is a fine, steady player. And at times even a brilliant one. At single jigs it would be hard to beat him, though in general execution his style may be considered too open and flute-like. However, that is a matter of individual taste. As regards time, he stands pre-eminent; his last bar of a jig or reel, in fact of any tune, is played in precisely the same time as the first, and no dancer can influence him to accelerate his pace or tempo.

Mr. O’Mealy, the well-known piper and pipemaker of Belfast, who played in concert with him on various occasions, speaks very highly of his social qualities. Nothing else could have been expected from his father and mother’s son, anyway.

Differing from his brother, John and William, at least in one respect, he stuck to his first love-the Union pipes-and, notwithstanding his musical education acquired under Herr Blowitz of Ferns, his taste for traditional Irish music remained uncorrupted and undiminished. All three became skilful pipers under the instruction of their father, Samuel Rowsome, the famous farmer-piper of Ballintore, Ferns, County Wexford, and all three have won distinction in that line of musical art.

The “Harvest Home” was an established institution at Ballyrankin, Clobernin, Farniley, Morrison’s, St. Aidan’s Palace, and many other residential seats of the wealthy in north Wexford. The attendance of the three brothers was ever in requisition at those annual celebrations, “Willie’s” reputation as a violinist being less than that of his elder brothers as pipers, only in the degree that the fiddle is deemed an instrument inferior to the Union pipes in giving to traditional Irish music its characteristic tonality. The “Harvest Home,” be it understood, was essentially the same as the “Flax Mehil” in other parts of Ireland-all private festivals-the assembly consisting of the family, friends, employes, and invited guests.

During this period Thomas Rowsome became closely associated with the late James Cash in his periodical visits to the Rowsome homestead. Together “Young Cash” and the youthful enthusiast would proceed to a secluded nook in the garden, or, the weather being unfavorable, to a private room in the house, and indulge in long-sustained spells of practice, for everything new in music which the wanderer had picked up on his rambles through Munster and Connacht he would impart to his beloved protégé. More than once old Mr. Rowsome Would come upon them in the act of playing one instrument together, each with one hand fingering the chanter.

“Tom, you will become a great piper yet,}’ Cash would say, as a presentiment of his own impending death would cloud his brow. “The music of your chanter will thrill audiences when the name of James Cash will be but a reminiscence or merely the subject of unsympathetic gossip.” The forecast was prophetic, for he died in his thirty-eighth year, while his friend Thomas Rowsome, now a municipal employe of the city of Dublin, has made a name for himself in the world of music. His engagements are many, not alone in his native land, but on the stage and in the halls of London, Glasgow, and other cities and towns across the Channel, where the mellifluent tones of the “Irish organ” in the hands of a capable performer never fail to arouse the most enthusiastic applause.

About forty-six years of age, over six feet in height, handsome and of impressive appearance, “Tom” Rowsome may not owe all his popularity to his musical gifts. He is also accused of being both genial and kindly, yet apparently insensible to female charms. Whoever the “King of the Pipers,” may be, an ardent admirer insists “he is one of the Princes and Heir Presumptive.” Still there are others.

Murder will out, and so will music, and, though the days of fostering patronage and encouraging recognition are past, the divine art, whether begotten of nature’s whim, or vitalized as a manifestation of the laws of heredity, may be relied on to find some outlet for expression, but it will be noticed that environment and opportunity have much to do with determining the favored instrument.

To maintain the traditions of his family, what else could this promising scion be but an Irish piper, his father, and grandfather, before him having been worthy representatives of the class? Had they been fiddlers, no doubt he would have followed in their footsteps. Still we must rejoice in his choice, for, while we are likely to have with us always raspers, fiddlers, and even violinists, we cannot but regret that performers on the Union or Irish pipes-the real national instrument of the people-are declining in numbers year by year and may eventually become extinct, like the harpers, their predecessors.

This young musical aspirant, on whom will depend to a considerable degree the preservation of his art, is the eldest son of William Rowsome, piper and pipemaker of Harold’s Cross, Dublin, and grandson of Samuel Rowsome of Ballintore, Wexford, elsewhere mentioned.

Born September 25, 1895, he commenced his musical practice under his father’s tuition when but twelve years of age. Such was his proficiency on both chanter and regulators that he won many prizes, and had been highly commended for taste and style by the best judges of pipe music, though but a boy of only sixteen birthdays.

If appearance counts for anything, we are justified in assuming that the future has no small distinction in store for him.

The instrument on which he is represented as playing in the picture was manufactured by his father, and is of full tone and concert pitch, blending harmoniously with violin and piano.

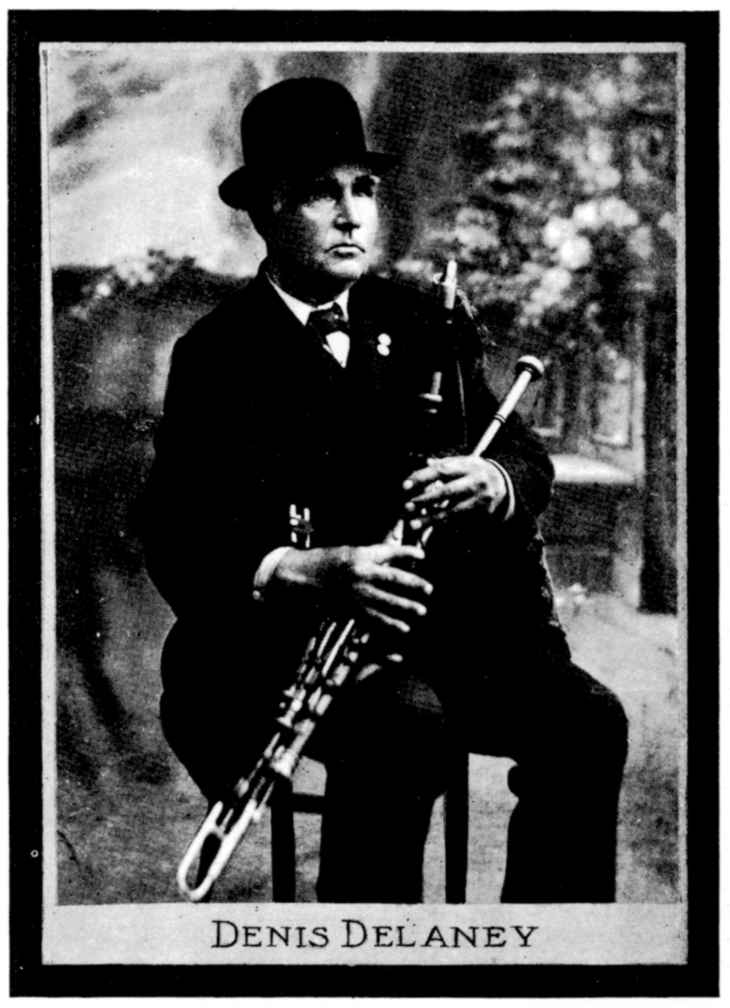

One of the few surviving, good, old-time players of the rollicking style lives in his native town of Ballinasloe, County Galway. Robust in build and ruddy of complexion, he is one of the central figures in its life, and in its celebrated fair.

Though totally blind, he is, strange to say, unsurpassed as a judge of cattle and other kinds of farm stock, and so well recognized is his skill in this respect that at fair and market his opinion is eagerly sought when trading is in progress. Stranger still is the fact that furniture moving is his principal occupation. With a table on his head, or a cupboard on his back, he can make his way safely all over town. To see him thus engaged and without a trace of timidity in his footsteps, a stranger would never suspect that he was blind.

Gifted with great conversational powers, an endless fund of humor, and a tenacious memory, he is naturally the life of every gathering which he attends. With such attractions, not to mention his qualifications as a prize-winning piper, we can understand how he won the heart and hand of a buxom young colleen half his age, it being his second matrimonial venture.

The jolly Denis, having “seen” to the burial of an old friend and brother piper, naturally “came in” for his beautiful set of pipes. He disposed of his own superannuated set, made by the elder Kenna in 1781, to Mr. Wayland, the irrepressible enthusiast and untiring promoter, of Cork, he being the fifth proud possessor of this specimen of Kenna’s handiwork.

The first owner after coming from the hands of the maker was a Mr. Burke of Tyrquinn, near Athenry, County Galway, and their cost ten pounds. By bequest they became the property of Mr. Burke’s nephew, Mr. C. Natton, of Kingstown. Dublin, from whom Denis Delaney purchased them in 1873.

In friendly rivalry at a big concert in Dublin, Mr. Delaney and Prof. P.J. Griffith played their respective versions of the “Fox Chase,” and, while both delighted the audience with their performance. It was freely conceded that Prof. Griffith’s version of that famous but much varied composition was the better.

The humor of the situation so appealed to the versatile “member from Cork”-John Smithwick Wayland-that he unlimbered his muse, so to speak, took his pen in hand and dashed off the following racy dialogue which led to striking effects:

WARPIPES VERSUS FIDDLE

Said the fiddle to the warpipes, “What is all this noise I hear?

You have challenged me to combat, so ‘tis whispered in my ear;

Your form is most ungainly, and your arms and legs too long,

Puffed up with cheek and pride, you can’t accompany a song.”

Said the warpipes to the fiddle, “’Tis just what I’d expect—

You’re like a barque forlorn, on the point of being wrecked;

And don’t you talk to me, Sir, of puffing or of blowing,

For I’d much prefer that kind o’ work to scraping and a bowing.

And it shows that I’ve the wind in me, to help me through the battle,

While you have to rely on but an empty, worthless rattle;

And if you stood before me, you would soon he on the ground,

For we know that empty vessels always make the greatest sound.”

The fiddle then got “crusty” and his bow he did let fly:

There was varnish, hair, and resin, flying everywhere sky high;

The fiddle turned yellow, and the warpipes turned blue,

Each returned to the onslaught, angry words they did renew.

Said the fiddle to the warpipes, “You’re all made up of drones,

You can boast of but one octave, and you have no semitones.”

Said the warpipes to the fiddle, as his eyes now flashed with {ire,

“For untruthfulness and impudence you come second to the LYRE-

You mentioned just awhile ago about my arms and legs,

But you can boast of none at all, for you have only pegs;

And what is more, I say, sire that your head is only glued,

And anyone can see, sir, that you’re very often screwed.,’

Said the fiddle, “I’ve a belly and a back and sides, moreover,

And a shift or two at intervals, my nakedness to cover;

I’ve a head-piece and a tail-piece, and though I’m often tight,

I’ve a bridge to rest my bones upon when I retire at night;

My audience I can move to tears, with feelings of emotion,

Without using golden syrup or any other lotion.”

Said the warpipes to the fiddle, “You are talking all rameis,

For I am far more welcome at a concert or a Feis;

I can be heard two miles off in spite of wind and Weather,

While your puny, squeaky music cannot scrape a crowd together.

You can amuse the children, so can a penny rattle,

But you will ne’er be fit, like me, to lead men into battle.”

Here the “seconds” gave a signal, simply by a beck:

And with that the warpipes rushed and caught the fiddle by the neck,

But this grip did not undo him, and only caused some fun,

For ‘twas very soon discovered that a windpipe he had none.

“I defy you to come out here,” said the pipes, in accents bold;

“Of course you won’t, you coward, you’re afraid of catching cold,

For your bridge would fall, your strings would snap, your voice would turn hoarse,

While the fresh air only strengthens me and gives me greater force.

This tap-room is no place for me, a coward I’ll be never,

So, Mr. Fiddle, you and I will have to part for ever.

Another word I would not parry with you for a guinea-

Your “ease” is lost and badly lost in spite of Paganini,

And though you boast your parentage to Stradivari of Cremona,

My lineage goes further back to ancient Babylonia.”

The warpipes then marched up the hill with erect and manly stride.

While Mr. Fiddle. Whose pride was hurt, committed suicide.

“Hung by the neck,” the verdict ran, as the neighbors all predicted:

‘Twas agreed by every juryman that the act was self-inflited.

Why the author should ignore the perfected Union pipes, in favor of the primitive instrument, in his dramatis personae, is not quite clear. Yet the outcome in a manner betrays the direction in which his sympathies lay. The fiddle’s finish is pitiably sad, and one cannot help regretting that the talented author did not relent in the last act, and with a magnanimity befitting the occasion, let the contest end in a “draw” at least.

As long as might continues to rule the world, and nations honor and ennoble the inventors of weapons for the wholesale destruction of human life, what chance has a flimsy, finical fiddle against a Shrieking, windy warpipe?

As a prize-winner at pipers’ competitions all over Ireland, we know of nothing to equal Denis Delaney’s record. Since 1897--the date of their origin—he has to his credit 29 first, 12 second, 6 third, and 1 special prizes up to the year 1912, according to his own account.

Accustomed as he had been to winning distinction for over a dozen years, his bump of self-esteem suffered no diminution in the night of time, and however much we may approve the decisions of the adjudicator in awarding the prizes to others at the Dublin Feis in 1912, we cannot help sympathizing with Delaney, whose pride had sustained a shock so severe that he hastened away without waiting to enjoy the subsequent festivities, or sit in the group of competitors for a picture.

A piper and a lover of piper music, kindly, unassuming, patient, tolerant, helpful, and hospitable—such is James Early as a man among musicians.

Free from professional jealousy, a proverbial affliction, he has been to the Union pipers of America what the lamented Canon Goodman was to the pipers of Ireland a generation ago—their unfailing friend in distress. An expert at putting a demoralized set of pipes in order, he had no superior as a reed maker, and although he had no monopoly in this line of delicate workmanship, the difference between his dealings and that of some others was the difference between liberality and covetousness, or between candor and duplicity.

From Boston to San Francisco, and from New Orleans to Manitoba came appeals for reeds, from pipers, amateur and professional, who were unable to fit their own chanters. They knew their man and they never appealed in vain. Many a time have we seen pipers come to Chicago from cities and towns a hundred miles away, for the special purpose of having their instruments put in order, and they were always hospitably entertained at the Early residence during their stay.

From Saturday evening until Monday morning Turlogh McSweeney made Sergt. Early’s house his home all throughout his engagement, which lasted six months, at the World’s Fair held in Chicago in 1893. Neither does “Patsy” Touhey concern himself about hotel accommodations when filling his theatrical engagements in the young giant city on the shore of Lake Michigan in more recent times. And that is not all, for many are the callers during the genial “Patsy’s” welcome visits, and no one need be told what happens in an Irishman’s house on such occasions.

Born at Cloone, near Carrigallen, County Leitrim, in the late forties, James Early learned to play the flute and fiddle when quite young; but, coming to America when but a boy, his practice was interrupted for many years while struggling with the vicissitudes of life in the mining territories of the Northwest. Coming to Chicago, he became a member of the police force in 1874 and fortunately met his friend and relative James Quinn, who enjoyed an enviable reputation as an Irish piper.

To acquire proficiency in music, everyone knows that early training is indispensable. Even so, our friend, infatuated with Mr. Quinn’s playing, though in the prime of manhood became the latter’s pupil. Rapid progress was the reward of taste and assiduous practice, and it was not long before he could play for dances with the best of them.

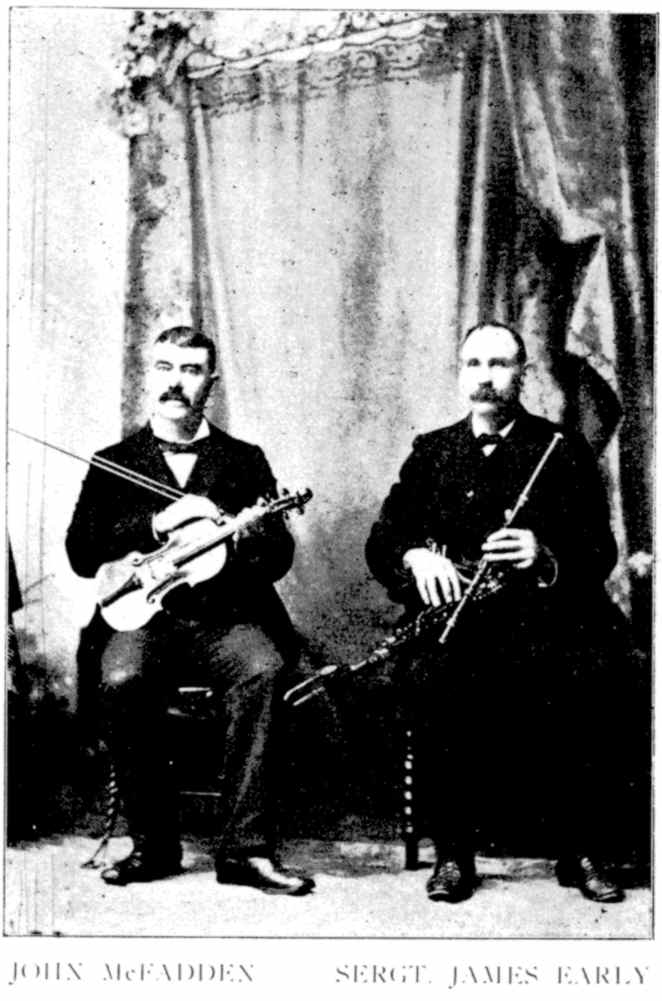

For a generation past Sergt. Early, in concert with John McFadden, a traditional fiddler of phenomenal execution, has played at public entertainments all over Chicago, and even in other cities in this and adjoining states on important occasions, their last being at the Chicago Feis, August 3, 1913, for the dancing contests.

With rare forethought the Sergeant kept a memorandum book in which he noted down the first few bars of “Old Man” Quinn’s tunes, from which he could always refresh his memory. As McFadden had also played with Mr. Quinn for years, many melodies derived from the latter were preserved and published for the first time in O’Neill’s Music of Ireland.

Although now retired from active service, like the writer, and living on the “sunny side of Easy street,” Sergt. Early has many pleasant years of life yet in prospect. Consequently we may hope to enjoy the music of our sires which he and his light-lingered partner “Mac” can render so delightfully in perfect time, tune, and execution, for many a year to come.

Quiet and unassuming, and silent as to music, unless the subject was under discussion, “Barney” Delaney betrayed no outward indication of being the marvelous jig, reel, and hornpipe player that he was. In fluency and rhythm on the chanter his execution left nothing to be desired—his style was truly the dancers’ delight., for he put the music right under their feet.

Like Gandsey, the Killarney piper, who in his childhood made music with the reeds which grew on the banks of Lough Lene, young Delaney fashioned a set of pipes from the feleastroms growing in the meadows near Tullamore, his birthplace, in Kings County. Music was in him and it early found expression on a penny whistle. In fact, to this day his self-taught system of fingering and tongueing on a whistle or flageolet is scarcely equaled by his execution on the chanter.

With the exception of a little primary instruction he received from “Jack” Foraghan, a Tullamore piper, Delaney was self-taught, and though capable of “cranning” or playing in the Connacht staccato system of execution, the free and rolling style with a liberal sprinkling of graces and trills was his favorite.

By dint of economy, while working as a laborer at the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia after coming to America in 1880, he saved the price of a small set of pipes made for him specially by “Billy” Taylor, the great pipemaker of that city. Equipped with these he Started for the west and finding appreciative people in Chicago, among them the present writer, he settled in the western metropolis permanently.

For a time after his arrival in Chicago, Delaney played in a concert hall, but was induced to accept an engagement with Powers’ Ivy Leaf theatrical company in place of “Eddie” Joyce, who took sick in that city. So satisfactory did he prove in every respect that his temporary engagement was made permanent with an increase of salary.

His friends and admirers in Chicago were bound to get him back, however, so the writer contrived to intercept the play in New York. And escort the piper home to Chicago, Where a position in the Department of Police awaited him. But this was not his only theatrical experience. Some years later he was given leave of absence to help Mr. Powers out of a similar difficulty during the sickness of John Moore, the company’s piper.

During his residence of over a quarter of a century in Chicago, he has played at one time or another on every important stage in the city, including Central Music Hall and the Auditorium; at picnics and excursions without number, and he has been practically kidnapped more than once by delegations going to New Orleans in cars specially chartered for some important occasion. From an incident in his younger days in Philadelphia we get a sidelight on his popularity with dancers. Once while playing at a dance, Taylor, said to he the greatest Irish piper of his day, was called away temporarily. To oblige him, Delaney put on the pipes and played for the dancers during his absence. The rhythm and swing of his performance were so pleasing that the dancers insisted on his continuing after Taylor’s return.

Unconcerned and self-possessed under all circumstances in public or private, he plays on undisturbed by an excited partner, who forgets when to change or repeat; and, to crown all, his instrument is sure to he in perfect tune, for in the mechanical art of putting or keeping an instrument in repair he has nothing to learn. Writing to a friend, of his experience while visiting Chicago in 1905, Father Jones of Ballyferriter says: “While at the musical entertainment that out-and-out wonderful piper, “Barney” Delaney, held me spellbound during those hours of gladness.”

The simplest tune at his hands took on a new expression and became a marvel of melody, so instinctive was his fancy and finished his execution.

Following this litany of perfections we must admit that we do not regard Delaney as a fit subject for canonization. In his earlier years he poured out his melodies without restraint, but when he found that they were being memorized and played by others, he became secretive and regaled his hearers, even his best and most intimate friends, with nothing but “chestnuts.”

Occasionally, when in the right humor and the listeners had no capacity for memorizing, he would play a string of rusty ones preserved for special use. Yet in the matter of enlarging his own repertoire no one was more acquisitive. Deprecating the decadence of Irish music, and deploring the decline of Irish piping, like John Coughlan the great Australian piper, Bernard Delaney could not be induced to teach his art to old or young.

Were he a “knocker” or afflicted with proverbial jealousy we would be inclined to believe that he cherished the conviction so common among his class, that when he died the last of the pipers was gone. But he is neither. Liberal as an entertainer, he was a miser with his tunes, and it is a certainty that quite a few of them, if not already forgotten, will die with him.

Being a good business man he has grown wealthy for a piper or policeman. After twenty-four years’ continuous service with a clear record, he retired on a liberal pension on the first day of March, 1912, to enjoy life at his latest home at Ocean Springs, Mississippi, and be fanned by the breezes of the Gulf of Mexico for the rest of his days.

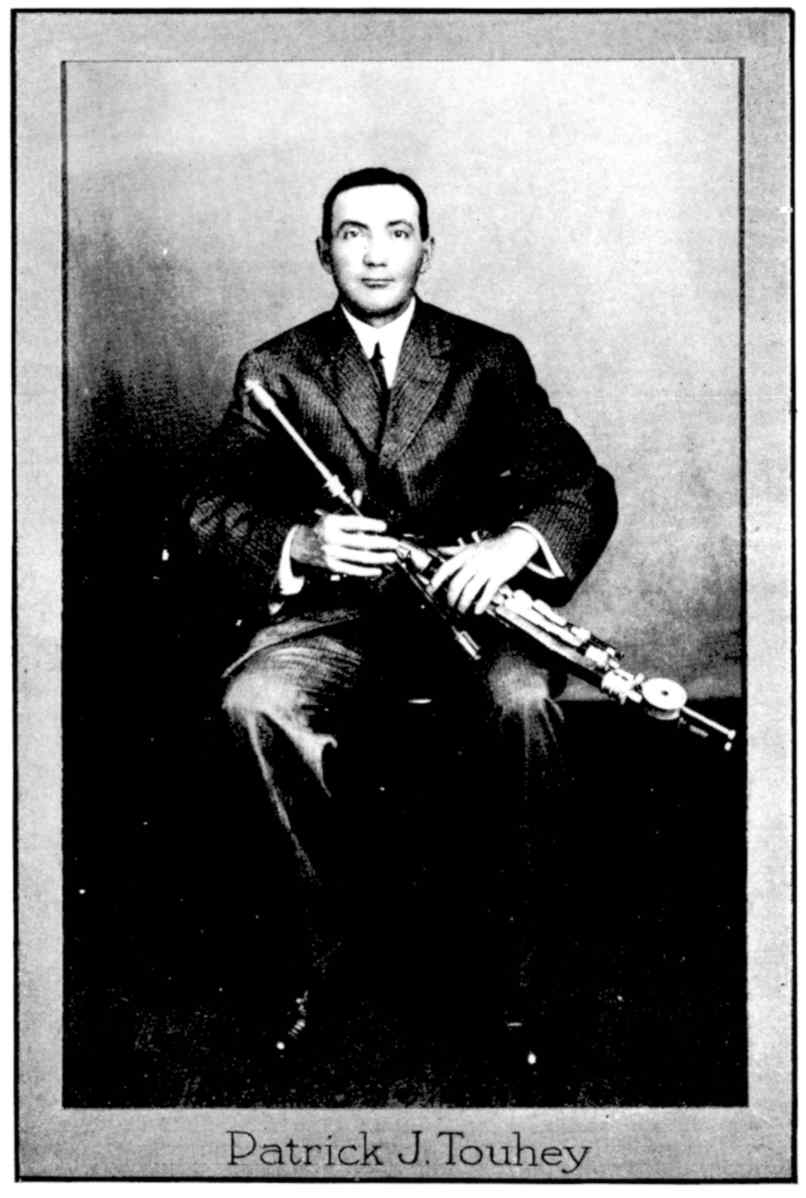

The “Only Patsy Touhey” among his admirers, and they are legion, is the youngest of the many distinguished pipers who hailed from Galway. He ranks easily at the head of his contemporaries from his native county and province, and it is contended by many that he has no equal anywhere. He was born at Loughrea, February 26, 1865, and came of a family in which musical talent was hereditary, he being the third generation noted for proficiency as an all-round performer on the Union pipes.

His father, James Twohill (that being the older form of the Irish surname O’Tuathail), born in 1839, was an excellent piper who played for the local gentry almost exclusively. The elder brothers, John and “Pat,” born in the years 1831 and 1836 respectively, rambled through England as professional pipers. John died in early manhood, but “Pat,” who was a fine performer, enjoyed a long life. Michael Twohill, grandfather of the subject of our sketch, born in 1800, in the same county, is reputed to have been a celebrated piper in his day.

Our hero “Patsy,” when less than four years of age, was brought to America by his parents. He had not commenced to learn music before his father’s death, being then only ten years old. But he was subsequently taught by Bartley Murphy, his father’s pupil, a Mayo man, and took what may be regarded as a post-graduate course with John Egan, the “albino piper,” elsewhere mentioned.

Together they toured the Atlantic cities for a year or so. Both had great command of the regulators. The resounding organ tones which a skilful performer can produce on them as an accompaniment to the treble, is a never-ending source of wonder to an audience.

While Turlogh McSweeney, the “Donegal Piper,” may have fittingly represented an antiquated and oppressed Ireland, playing his ancient instrument outside the entrance to Mrs. Hart’s “Donegal Castle,” at the World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893, the hopes and aspirations of a regenerated nation were pleasingly typified in “Patsy” Touhey, the spruce young man in corduroy breeches and ribbed stockings, whose expert manipulation of a great set of Taylor pipes made him the centre of attraction within.

When Myles Murphy, manager of the “Irish Village” at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition held at St. Louis, Missouri, in 1903, determined to obtain the best talent for his concession, he engaged “Patsy” Touhey at the latter’s own price. And it proved a capital stroke of business for Mr. Murphy at that.

So novel and captivating was his performance of all varieties of music on the Irish pipes on the stage of the Irish Theatre, that the members of the “International Association of Chiefs of Police,” about 200 in number, who attended the play in a body, encored his playing repeatedly, and wanted him to continue his wonderful music indefinitely’ but four encores were all the stage manager would allow.

Neither sentiment nor early associations had much to do with this acclaim, for the majority of those present were of other than Irish ancestry, and of the latter less than half were of Irish birth.

As comedian and piper Touhey has been before the American public all over the United States for years, and while at this writing many hundreds of theatrical people are out of employment, it speaks well for his standing with the public that he is rarely without an engagement.

His advent in Chicago to fill theatrical engagements is an event of much concern to his many friends and admirers, who anticipate an afternoon and evening of unalloyed pleasure in his company. “The gathering of the Clans,” at the hospitable homes of Sergeants James Early or James Kerwin is always attended with a “feast of music and a flow of soul” unrestrained by diffidence or formalities.

Agreeable in personality and obliging in disposition, he is deservedly popular. A stranger to jealousy, his comments are never sarcastic or unkind, neither does he betray any tendency to monopolize attention in company when other musicians are present. In fact, Touhey is a notable exception in many ways, and if he possesses any less admirable qualities they have escaped the notice of the writer, who has enjoyed his acquaintance for over a score of years.

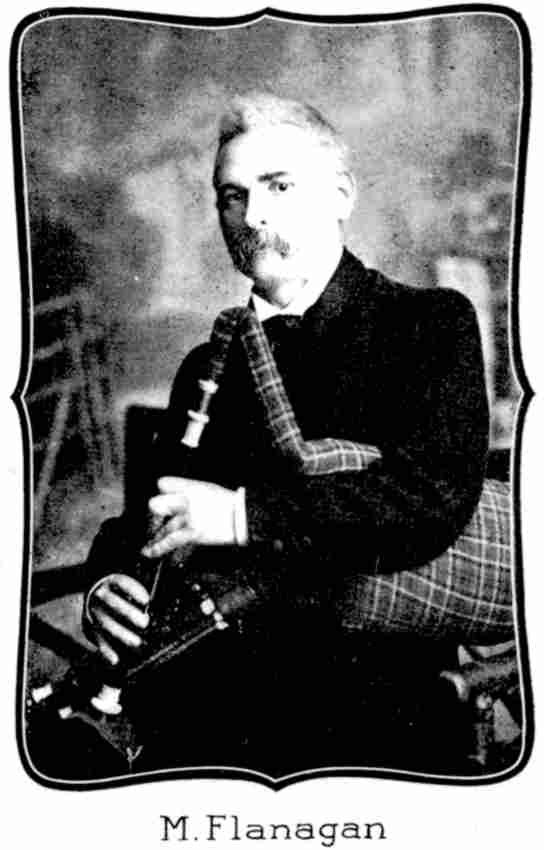

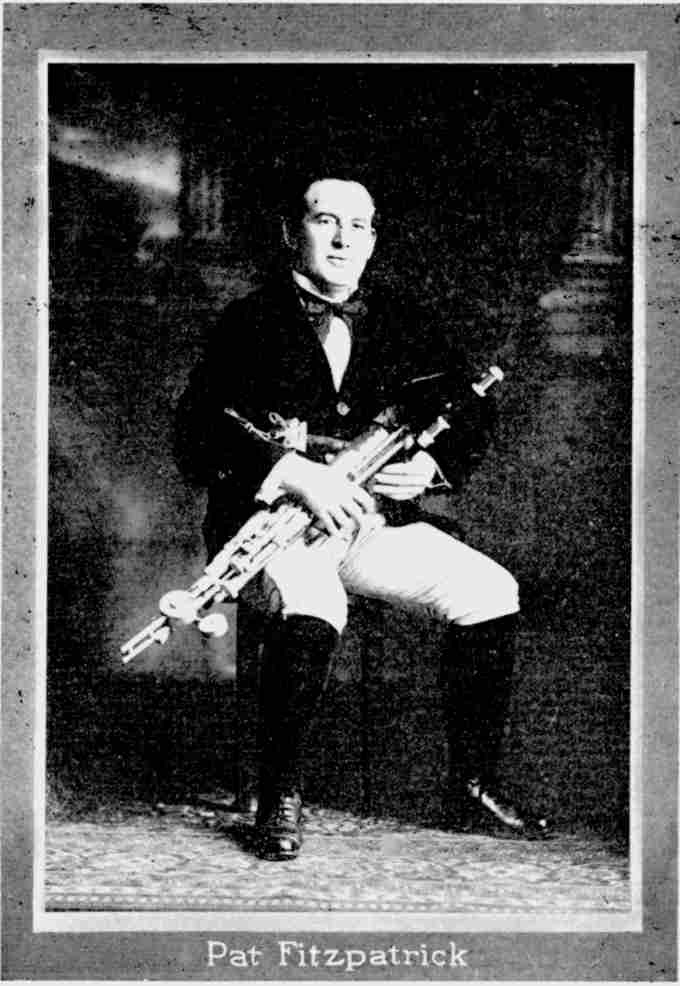

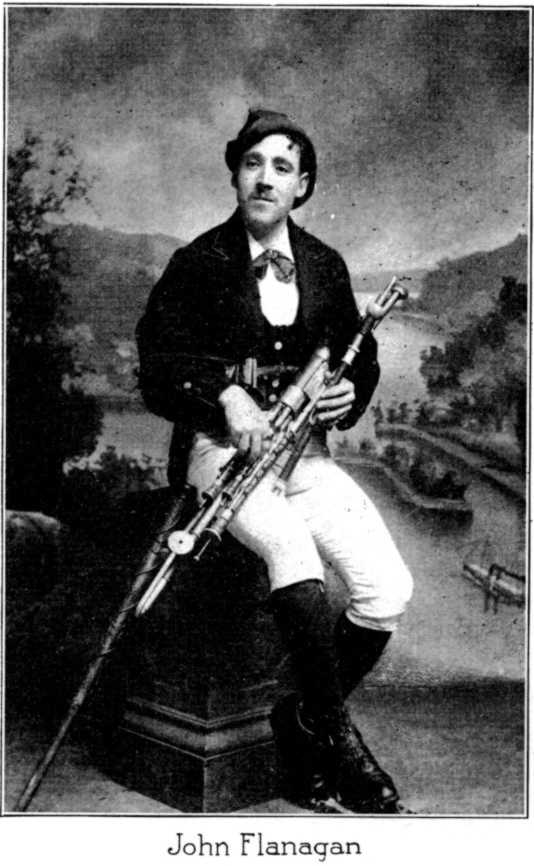

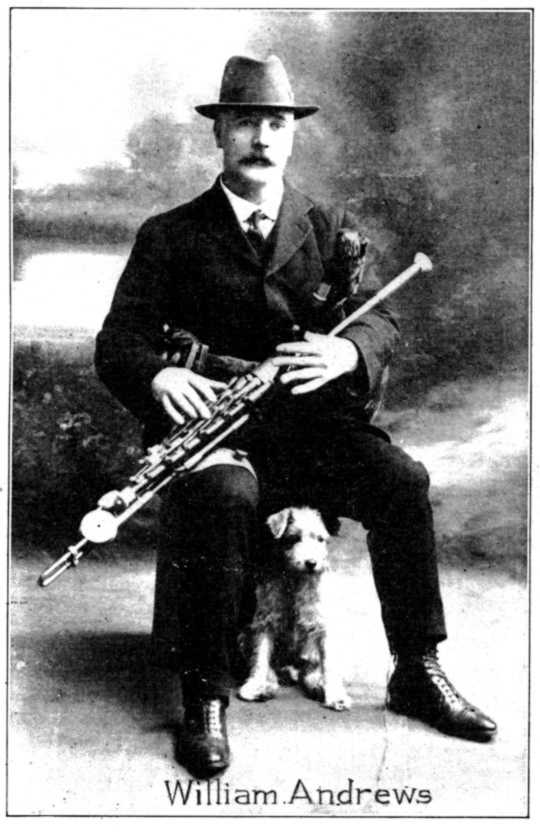

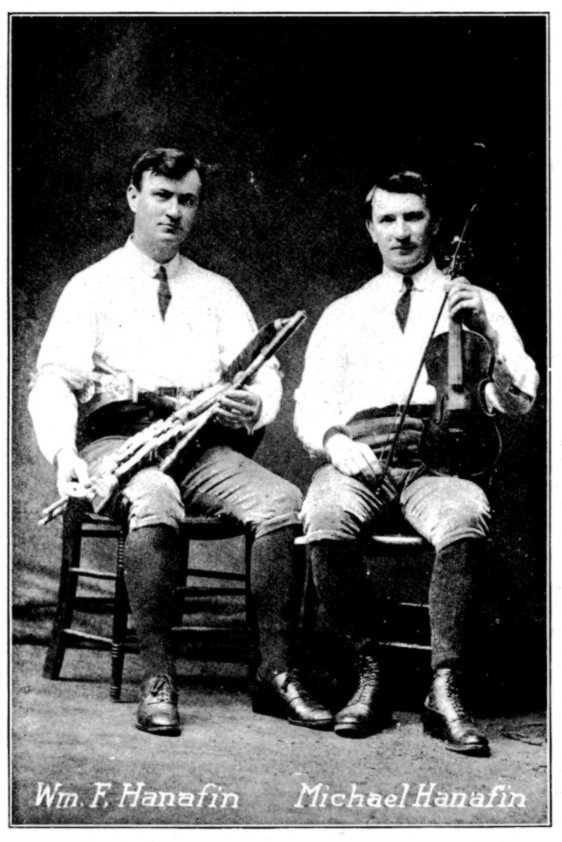

In a muuch appreciated communication to the present writer in 1911, giving an account of the early life of John Hicks, the “Kildare Piper,” mentioned in Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby, Mr. Flanagan not only disclosed certain features of his own boyhood days, but betrayed the fact that, besides being a trained musician himself, he was a man of education and uncommon literary ability.

Restrained by a modesty, oh! so rare among favorites of the muses, his communications to the Dublin press on musical affairs, were published anonymously or otherwise disguised.