CHAPTER XXIII

FAMOUS PIPERS

MANY a fine performer on the Union pipes nourished in the last half of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth centuries, and even later, whose names have vanished on the wings of time. Others again there were of whom little is now remembered but the names, and even that slight concession to tame is due more to chance than design.

If we have failed to meet the expectations of our readers by the omission of deserving names, or by the paucity of our remarks in other cases, we can only plead that every available scrap of information has been utilized in the preparation of this work, which deals largely with a class conspicuous in Irish life, yet slighted in Irish literature.

It is surprising how many pipers of note came from within a radius of half a dozen miles of the town of Edenderry, in Kings county, close to the borders of Kildare. Trinity Sunday was an eventful day in the parish of Carbury generations ago. A holy well in a gentleman's demesne close to Carbury castle was a Mecca to which hundreds hied on that day. A “patron” originally of a religious character was an institution in that locality, with the usual accompaniments of courting, dancing, drinking, and even fighting. Thither came people from ten or twelve neighboring parishes and those gatherings naturally attracted wandering minstrels from near and far. The consequence was that the district became a rich repository of Irish Folk Music.

Edward Dowdall, who early in life went to Dublin, was born in the same parish as Maurice Coyne, the famous pipemaker. “Eddy” Dowdall, as he was called, was taught either by “Thady” Devaney, or Peter Cunningham. Devaney also taught “Tim” Ennis. The expert chanter manipulator mentioned in the biography of John Hicks. Ennis, Dowdall and Devaney were reckoned very good pipers in their day, which was in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Another good piper of whom Grattan Flood makes mention was Garret Quinn of Enniscorthy, Wexford. Quite likely he was the “Piper Quinn” who kept a drinking bar and dancing saloon at New Street, Enniscorthy, some sixty or seventy years ago. He played the double bass himself in the string band which was part of his establishment. Old-timers are still living who remember seeing “Piper Quinn and his big fiddle” at the fair of Scarawalsh. His son Patrick was a famous traditional fiddler in a later generation.

Through the kindness of Officer William Wa1sh of the Chicago police force, we present the names of some Connacht pipers unknown to fame, as they had never rambled beyond the confines of their native province. Though a native of Oughterard, County Galway, Officer Walsh is an accomplished “Highland piper,” and a writer of pipe music.

Between the fifties and eighties of the nineteenth century there rambled through the said county, “Paddy” Green, a blind piper from Tuam; “Paddy” Kilkenny, who hailed from Clifden; and John Lennan of Kilkerin, who achieved considerable repute throughout Connemara.

Martin Moran was a native of County Mayo, and Charles Daly, though born in Clara, spent most of his time in Galway. There was another piper, known only by the name “Eunachaun,” who for neatly thirty years enjoyed enviable popularity in Iarconnacht. No wedding or christening could be properly celebrated without the piper and his music in that district or in Connemara in the “good old times.”

A piper named Martin Curley, whose antecedents are unknown, was, according to Mr. Quinn, a famous Chicago piper, the best reel player he ever heard. Not less famous was a piper named Cribben, of whom we know nothing except that he hailed from Swineford, County Mayo, and that “Jimmy” O’Brien was one of his pupils.

In an Irish lyrical song given by Professor O’Curry to Dr. Petrie, mention is made of Shane O’Finnelly playing “Ree Raw” on his pipes, and by the way, it is said that the professor obtained some fine tunes in 1853 from a piper named Michael O’Hannigan.

Quite a number of the tunes in Dr. P.W. Joyce’s collections were noted down from the playing of James Buckley, a piper in the barony of Coshlea, in the southeastern part of County Limerick, who flourished in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

Anthony Kennedy—briefly called “Tony”—of Carrigranning, County Longford, although a tinsmith by trade, was a fair performer on the Union pipes. His son, “Tony” the younger, who lacked nothing of equaling his father’s abilities either way, played the pipes at his father’s wake. This, be it understood, was done in no spirit of levity butt, on the contrary, out of respect to the old man’s fondness for the music of his favorite instrument.

The O’Farrells of County Longford—father and three sons—were not distinguished for brilliancy of execution on the chanter, and they made no pretense of manipulating the regulators. Yet, playing altogether at the fair of Longford, Mr. John Gillan tells us, they attracted a large and appreciative audience around the middle of the last century.

An excellent piper named Fitzpatrick, who flourished about the same time, frequented Miltown, Malbay, and other places of public resort on the Atlantic coast of the County Clare. He was not much over forty years old when Officer John Houlihan met him in 1860 at the fair of Dunbeg, some five miles northwest of Kilrush.

We are indebted to Grattan Flood for the information that a famous piper named O’Mahony flourished in Wexford in 1832, and that David Cleary was no less distinguished in 1840 in Limerick.

Tradition has preserved the name of Kitty Hanley, a Limerick widow, who on the death of her husband—a blind piper—buckled on his pipes and made a living playing on the streets—a prototype of “Nance the piper” of Castlelyons, County Cork, elsewhere mentioned.

A writer in the Dublin Penny Journal of October 18, 1834, briefly refers to a Munster piper named “Jack” Pigott, whose playing of “Cush-na-Breeda” (Beside the River Bride) was the ne plus ultra of bagpipe melody. This bare allusion is all that has hitherto preserved from oblivion the name of a piper so proficient, as far as Irish literature is concerned.

Mathias Phelan of Cappoquin, County Waterford, must have been a piper of some consequence to have his instrument deposited in the National Museum, Dublin.

As late as the early sixties a piper named Shannahan, who was a native of Kilrush, County Clare, had a great reputation in Kerry and Limerick. He was the father of Michael Buckley Shannahan, the celebrated violinist, according to Prof. P. D. Reidy.

Another famous piper remembered by the professor was Timothy O’Gallagher, commonly called “Theig O’Gollahoo” as the name sounds in Irish. He hailed from Clonfert, and “played most excellently” for an exhibition in the sixties.

The Daniel O’Leary of Mallow, County Cork, to whose splendid performance at Dinis Cottage, Lakes of Killarney, Professor Reidy listened for hours, in the late sixties, could hardly have been the piper of identical name, mentioned by Grattan Flood as having flourished in the forties and fifties, and being the clan piper of “O’Donoghue of the Glens.” Much less probable was he the “Duhallow Piper” described by a writer in the Dublin Penny Journal of October 18, 1834, who was a diminutive hunchback.

As far back as the second quarter of the nineteenth century, a farmer named Dudley Gallaher of Lisnatulla, near Ballinamore, County Leitrim, had a wide reputation as an Irish piper. The chanter of his pipes was recently brought to Chicago by James Kennedy on his return from a visit to his native home. The wood is lignum vitae.

Oldtimers remember the names merely of “Rody” Slattery of Cahir Tipperary, and one Moriarty of Kerry, as being fine performers generations ago, but no details of their lives are now available.

Casual mention has been made of Patrick Gallagher, a capable piper of Lewisburgh, barony of Murrisk, County Mayo, who passed away in the last decade; and of one Malloy, who, when his little crop is sown at Doon, Parish of Killannan, County Galway, resumes his role of traveling piper in the “north countrie.”

“Pat” McCormack of Ardee, County Louth, would have remained unknown to more than local fame had he not been brought to Dublin to play at the Pipers’ Concert in 1903, and delighted the audience with his performance on the double chanter.

Merely as a matter of information, we may add that Ashley Powell of the Cork Pipers’ Club—one of Mr. Wayland’s pupils—is said to be playing the Irish pipes in the land of the Pharaohs.

In a very interesting article on “The Irish Musical Revival,” by Morgan P. Jageurs of Parkside, published in The Advocate of Melbourne, South Australia, we find many of the missing links not otherwise obtainable in our sketch of John Coughlan, the most renowned Irish piper of the Island continent.

Other Irish pipers in Australia, the author says, were Patrick Clarke of Ballarat, Victoria (1865); J. Connelly, who returned to San Francisco after a few months’ residence in Melbourne; Owen Cunningham, formerly of Boston, U. S. A., who played on the streets of Melbourne and Sydney in 1868; also one O’Connor of Sydney. In more recent times, and the late John Fraser of Glenmaggie, Gippsland, Victoria, who was noted as a skilful performer, though unfortunately his talents were confined to the quiet country districts in which he lived. J. Critchley of Rockleigh, South Australia, elsewhere mentioned in connection with Mr. Patrick O’Leary, is described by Mr. Jageurs as equally proficient on the Union pipes and Warpipes. Other great Irish pipers, not generally known but whom he names, are: Daniel Rahilly of Killarney; Lawrence Minahan, also a Kerryman; and Denis Duggan, the “Duhallow piper” (County of Cork), who on account of his excellence was usually engaged for the dancing competitions.

It would appear that, released from home influences, some of the clergy have been moved to make amends for the attitude of their cloth in the motherland. What else can we understand from the following: “The Perth Irish Warpipe Band, West Australia, founded by the Rev. Fr. T. Crowley, P. P., who, with another Sagart, played in its ranks, brought out an expert piper, Mr. Richard Evans, from the City of Cork a couple of years ago. He, too, plays both instruments.” And now, by the way, they have induced the tireless enthusiast and organizer, John Smithwick Wayland, founder of the Cork Pipers’ Club—the pioneer organization—to emigrate to Perth, with his passage and expenses paid in advance.

More extended accounts of Cunningham and Connelly may be found in the preceding pages.

In his correspondence, John Coughlan, the great “Australian piper,” alludes to James Kelly as a performer who ranked with the famous Patrick Flannery and his nephew, William Madden.

A very capable performer on the Union pipes of the few tunes comprising his theatrical repertory, was “Charley” McNurney, the musical member of the “Callahan and Mask” vaudeville combination, which toured Australia very early in the twentieth century.

Some four or five days after their first performance at Sydney, Mask was approached on the street by a man whom he recognized as the occupant of a seat in the front row at every performance.

“Excuse me, sir,” said the man, “but would you mind telling what might be the tail of your name?”

“The tail of my name! What do you mean?” answered the piper, in surprise.

“Oh, I mane no offense at all, sir; only surely there must be something afther Mack.”

“So there is, indeed,” replied the man of music, good-naturedly. “My name is McNurney.”

“For God’s sake, Mr. McNorney,” exclaimed the fascinated exile, “is there only three ‘chunes’ in the pipes? Night afther night I’ve been going to hear you play, but never a ‘chune’ comes out of your chanter but the same three.”

Of course the disappointed lover of the music of his motherland was not aware that “Charley” McNurney was but following the custom of musicians and vocalists in the theatrical profession, who seldom vary the favorite numbers in their program.

“Mack” has a bag full of “chunes” for that matter, being the son of Alderman McNurney, a wealthy horse-shoer, and a very capable amateur piper, but those he repeated so frequently on the stage were his masterpieces.

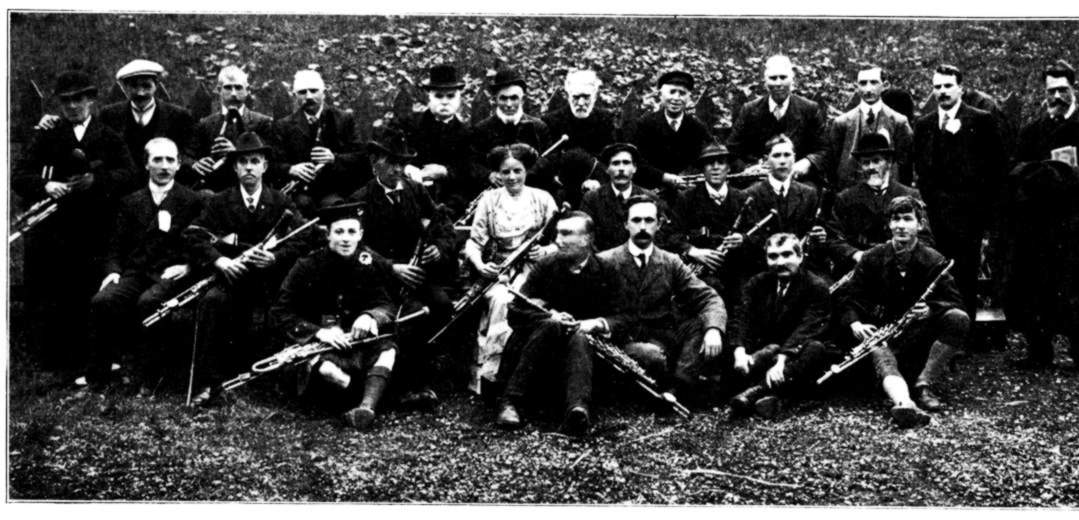

Great credit is due Michael O’Duibhginn, secretary of the Dublin Pipers’ Club. Who through his capacity and energy brought to the Oireachtas of 1912 no less than seventeen Union pipers—the largest number of the fraternity ever assembled at such a gathering. And then, to crown his efforts, a versatile member of the club—Seamus ua Casaide—took his pen in hand and gave to the press a gossipy sketch of the proceedings and those who took part in the event. Interesting as the picture of the group—reproduced in our pages—may be at present, we regret to foresee the day that it may be historical.

Among the pipers who contributed to the success of the Oireachtas, eight had been dealt with elsewhere in our sketches; namely, M. Flanagan, John Flannagan, James Byrne, John Kenny, Denis Delaney, Patrick Ward, Stephen Ruane, and Nicholas Markey.

John O’Reilly of Dunmore, County Galway, the dean of the assemblage, won the highest honors jointly with James Byrne of Mooncoin, County Kilkenny. The former is described as “a blind man of smart appearance with a jet black goatee beard and clean shaven upper lip, which gives him the appearance of a returned Yank.” Though seventy-three years of age, not a grey hair gives warning of life’s decline. His playing, which was far superior to his performance of previous years, may be attributed in some degree to his splendid set of pipes, recently purchased from William Rowsome, the clever pipemaker of Harold’s Cross, Dublin.

Seamus MacAonghusa—otherwise James Ennis—of the Dublin Pipers, Club, who was awarded second prize, is a new Richmond in the field of piping. He was leader of the Dublin Warpipers’ Band, which won third prize at the Carnival, while Seamus himself achieved distinction by winning hrst prize in the individual warpipes contest, and also Francis Joseph Bigger’s prize for the best all-around warpiper.

Accompanied by Mrs. Kenny—”Queen of Irish Fiddlers”—this talented young man's playing proved how well the Union pipes and fiddle play in unison. As Union piper, Warpiper, and dancer, this native of the Parish of Naul in his round of triumph exemplified the possibilities of intelligent effort sustained by vitalized national sentiment.

Special prizes were awarded William H. Mulvey, “a pleasant-looking giant” of Mohill, County Leitrim, and Hugh Newman, a tall, thin piper hailing from Athboy, County Meath. Mr. Mulvey, it appears, won third prize at the Dublin Feis in 1905, second prize in 1906, and first prize in 1909--a very creditable record indeed.

Francis J. McPeake of Belfast and Mrs. J.J. Murphy of Limerick were awarded first and second prizes, respectively, in the learners’ class of Union pipers. The singing of the young man from the north to the accompaniment of his pipe music was a performance highly appreciated. Originally a pupil of R. L. O’Mealy of Belfast, temperamental difficulties came between them, so he placed himself under the tuition of O’Reilly, who spent some months in the Ulster metropolis.

Daniel Markey, a Union piper hailing from Castle Blayney, County Monaghan, is described as an active, low-sized man, resembling a seaman more than a musician, and a witty conversationalist in Ulster Irish. At the Dublin Feis of 1900, he tied with Denis Delaney of Ballinasloe for third prize, and he also won third prize in 1909.

Of Thomas Walsh, one of the group, nothing can be said except that he came from Dungarvan, County Waterford.

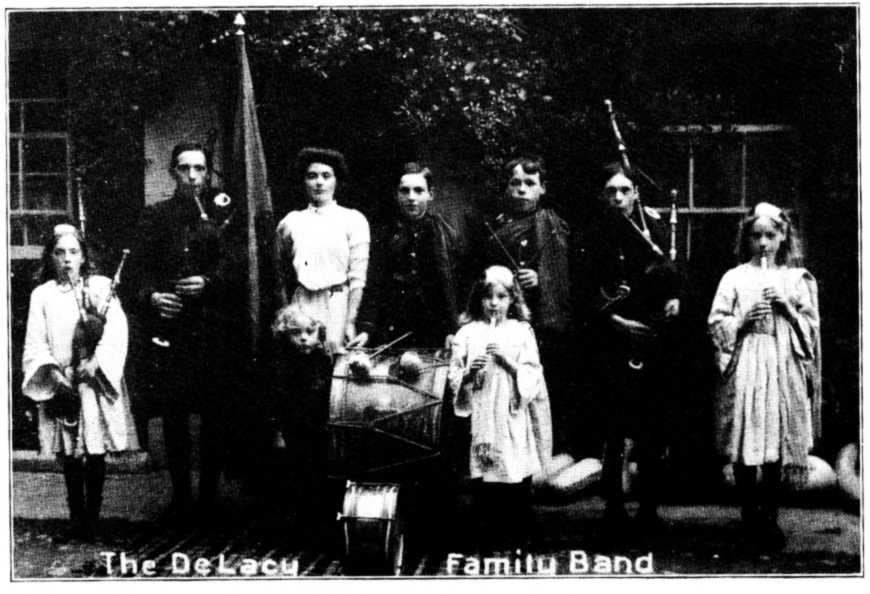

Probably the most unique band in Ireland is that composed exclusively of nine members of the DeLacy family, boys and girls, hailing from the townland of Tomsallagh, Ferns, County Wexford. As arranged in the picture their names are, from left to right in rear row: Eva Gertrude (known as Queenie), Patrick Thomas, Catherine Agatha Philomena, James Vincent, Richard Kevin, William Gervase, and Elizabeth Veronica. In front row: Leo Michael and Una Mona.

Just think of it, the DeLacy family of fourteen children brought up in a laborer’s cottage with only half an acre of garden! And, by the way, that same cottage and garden won first prize for care and crops for thirteen years. There’s a record from any point of view.

To the encouragement, training, and fostering care of Patrick Whelan of Scarawalsh, elsewhere sketched, the DeLacys owe not a little of the renown which their acquirements have won, although their first meeting, and the introduction of warpipes into Wexford, are due to the energy of John S. Wayland, founder of the Cork Pipers’ Club.

Judging from the accounts in the papers, it seems like old times again in Wexford. On Sunday evening “Tinnacross was the rendezvous for a genial, warm-hearted gathering from all the district around,” says one of them. “The occasion was an entertainment provided by the indefatigable DeLacy Warpipers’ Band, and surely never a social gathering was more racy of the best and kindliest Irish characteristics. It is surely an omen of a more healthy social life and an indication of what progress we have already made, along the road to an Irish Ireland. A growing nation—just as, thank God, Ireland is growing—must manifest itself in varying phases, and our concerts and entertainments were as much indicative of racial spirit and racial development as greater events. To the splendid little clan belongs the honor of holding a thoroughly Irish entertainment in Tinnacross, free from every trait of Anglicization and as amusing as concert could well be.” Nearly a column is devoted to giving a detailed account of the entertainment and those who took part in it, among them being Miss Una DeLacy and Master James DeLacy, whose dancing elicited repeated applause. “Three Misses DeLacy sang a pianoforte song with beautiful effect, the action being perfect and the singing a marvel.” Such a display of versatility in one family is difficult to duplicate.