CHAPTER XXIV

TYPICAL HIGHLAND PIPERS

DANIEL O’KEEFFE

ONE of the most noted characters in Chicago before the great fire of 1871, which practically destroyed the city, was “Dan” O’Keeffe, a dancer and performer on the Highland pipes. He was born at Rathmore, County of Kerry, about ten miles east of Killarney, in 1821, and died in Chicago in 1899, the wealthiest professional piper on record. In his youth he learned to play the flute, but on coming to America in 1847 he took up the practice of the Highland pipes.

Before settling down in the western metropolis he had toured the United States and Canada as a traveling piper. His watchword was “Get the Coin,” and he surely got it, for he knew the value of advertising when giving entertainments in many of the small towns in his itineracy.

Many of his escapades while traveling, when a squint through the peephole in the curtain showed but a slim attendance or “poor house,” made him an object of deep interest to the disappointed ticket buyers, who waited in vain for his appearance. Some of “Dan's” practical jokes had no element of humor at all from their standpoint. Should the box office receipts, even with a full house, fall into his hands under any pretext, the transfer of his slim baggage and himself to the first train-passenger or freight-was his only solicitude.

Anyway, the gay and festive “Dan” came to Chicago in the late sixties and opened a saloon on Kinzie Street, near the passenger station of the Chicago and Northwestern Railway, and, being but one square from the Chicago River, it was frequented by sailors, who are proverbially good spenders. But what attracted the most patronage was a large swinging sign over the door, on which was painted a Highland piper in full costume, playing the pipes and dancing to his own music.

As a special inducement to the passerby, it was announced on the sign that anyone who beat the proprietor in dancing a jig, reel, hornpipe, or Highland Bing, could have his drinks free for a week. Though not specially distinguished as a piper, competent authorities allow that O’Keeffe was an exceptionally fine dancer.

As far as we can learn, it is not recorded that any free drinks had been handed out, as a result of the standing challenge.

“Dan” O'Keeffe turned his talents, such as they were, to good account. He made money and invested it wisely in Chicago corner property, now very valuable. Late in life he undertook to play on the Irish pipes, but the attempt did not meet with the success anticipated. Many years after his death, which occurred in 1899, the instrument, dried up and disjointed from long disuse, came into the possession of Sergt. Early, who, after putting it in order, disposed of it to Robert Lawson. The latter, who was an excellent fluter, soon became a capable performer on the O’Keeffe instrument, and secured an engagement to play on the porch of the McKinley cottage in the Irish Village at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition at St. Louis in 1903. Years afterwards this splendid, sweet-toned set of Union pipes of the Egan make was stolen from Lawson at New York City.

After playing a few tunes in a Bowery bar-room, the piper was given some “knock-out drops”, and when he came to the next morning in some out-of-the-way place, he had neither pipes nor knowledge of where he had been “doped.” No trace of the instrument has been discovered from that day to this.

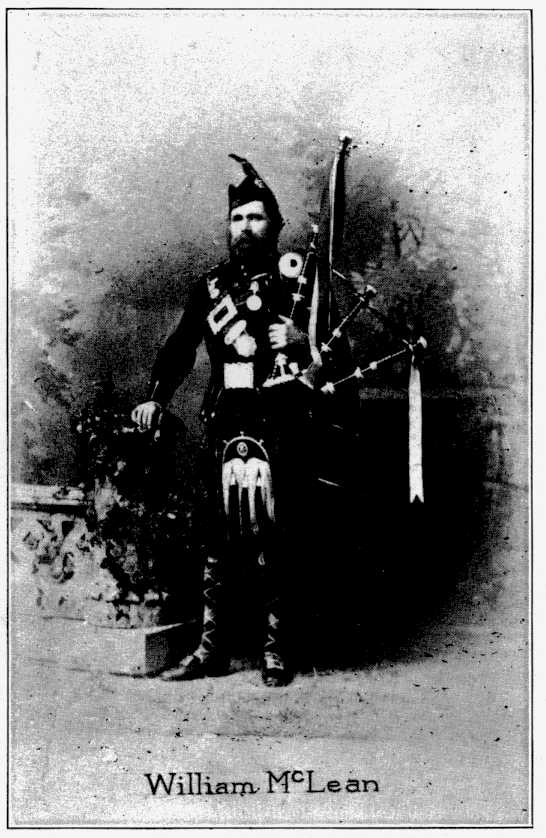

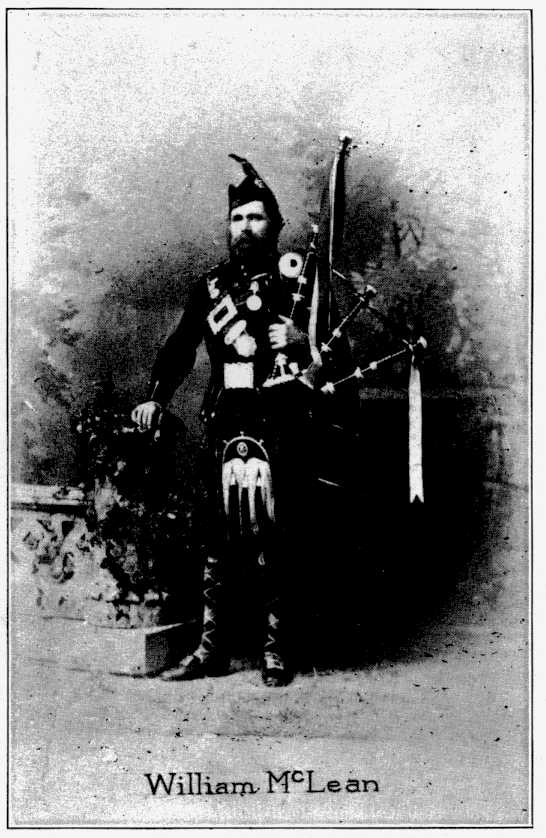

WILLIAM MCLEAN

Born in Ross Shire in the northern Highlands, in the first decade of the nineteenth century, William McLean was famous as a Highland piper in early manhood, and, if rumor is true, had no superiors when he was twenty-five years old.

Among his various avocations was that of cook in seagoing vessels. And his promiscuous intercourse with people of all nations no doubt added something to the natural urbanity of his manners. When the writer made his acquaintance in Chicago in 1875 his preeminence as an all-around performer on the Highland instrument was acknowledged. Unlike most Scotch pipers, his repertory was not confined to Scotch music. “Mac” was equally proficient on such Irish dance music as came within the limited compass of his chanter, but it was amusing to witness his bewilderment when he found his system of execution was ineffective on the diatonic scale of an Irish chanter.

He had engaged in the saloon business for a brief period before that date, and his music attracted a large patronage, but so sociable and absent-minded did he become that often he left the day’s receipts on the bar while he engaged in conversation with a friend. As a financier he was simply impossible not only in business but in all his transactions, and it was marvelous how he could discover such cheap and cheerless tenements as he invariably occupied with his family.

As we have stated, such was the excellence of his execution that no one but Joseph Cant made any pretense to rivalry. Surprises are always in store, and our hero was the victim of one of them at Milwaukee one Fourth of July. At a competition in which he took part, an obscure, fifth-rate piper was announced as the winner of the first prize, to the astonishment and disgust of the audience.

The adjudicator, it appeared, hadn't much of an ear for music. Anyway, and as it happened one of the competitors played “The Campbells are Coming,” the only tune known to the judge, what could the latter do but award first prize to the one who played it!

Well does the writer remember the winter when McLean filled an engagement to play for hours every evening in the large barroom in the temporary building at the southwest corner of Clark and Jackson Streets, where the Western Union Telegraph “skyscraper” now stands. At home he preferred to play the half-size bellows pipes, but in a barroom, especially of liberal dimensions, they could not compare with the Piob Mor in drawing a crowd.

Of all his callers, none was more welcome than “Willy” Walsh - now a dignified officer of the clergy - for when the latter hove in sight “Mac” knew he was in for a long rest. As the magnet draws the iron, so does the sight of a set of Highland pipes attract the willing Walsh. But to get them away from him, once he starts playing - ah, but that's a problem not so easily solved sometimes.

A birthday party at Bohemian Hall on DeKoven Street, when he was seventy- five years old - about 1880 replenished the old minstrel's depleted exchequer for the time being, but he soon found it advisable to make his home with his daughter at Saint Paul, Minnesota, where he lived to a great age.

Never afflicted with megalomania like so many of the musical fraternity, McLean was always genial, kindly, and helpful, and, though enjoying an occasional glass of kimmel when procurible, he never lost possession of his faculties, and he remained the same good-natured though thriftless genius to the end.

JOSEPH CANT

Another famous Highland piper who may be considered one of Chicago's early settlers was Joseph Cant, a native of Inverness. Born around the middle forties of the nineteenth century, he was an expert carpenter and cabinetmaker also. Coming to Chicago in early manhood he soon became shop foreman, but eventually branched out in the building business for himself, at which he has been quite successful.

Strictly a note player, “Joe” Cant was familiar with all standard Scotch pipe music. Nothing could attest his proficiency more convincingly than the fact of his winning first prize at the St. Andrew's Games at Dexter Park, Chicago, in 1877. A stranger from the West, he journeyed to Buffalo, New York, in 1882, and won the R. B. Adam medal (first prize) for marches, strathspeys, and reels, among nine competitors from Canada and the United States. The genial “Joe’ Was awarded a gold medal, first prize, played for three times in 1888 at the games of the Highland Society in Chicago and Milwaukee.

A tempting salary induced him to accept an engagement to play for an advertising firm throughout the western states on one occasion, and that was his only lapse into professionalism. An anomaly among musicians, Mr. Cant prefers to listen to others rather than play himself. Always appreciative, never harsh, nor even critical, he is the most companionable of men, and no native of the Green Isle is more keenly alive to the spirit of an Irish jig or reel. In fact, such is the liberality of his nature that he discovers merit in others not even suspected by themselves.

Music must have been in the family, for his brother, Andrew Cant, was for many years household piper to the Earl of Breadalbane.

Occasionally the subject of our sketch turns out a new set of pipes - the half-size reel set with stock and bellows being his favorite. Nothing in a mechanical way comes amiss to his hand, consequently he is the court of last resort to many who find his friendship indispensable.

PATRICK NOONAN

Contemporary with William McLean and Joseph Cant was Patrick Noonan. Though not so absolute a performer as they, he was better known than either, and for suavity of manner and powers of persuasion, few could hold a candle to him. Born in the County of Limerick about 1825, he had developed considerable proficieney on the Highland pipes before coining to America. After engaging in various occupations, including that of drayman, his blarneyed tongue secured him a life position in the general postoffice, Chicago, in the early seventies.

A born salesman and trafficker, he made a specialty of second-hand sets of bagpipes-Scotch and Irish-and their equipments; and he was forever engaged in negotiations with a view to their purchase or sale. He was quite liberal with his music and Without hesitation played all over town as a matter of accommodation, and thus enlarged the circle of his friends and patrons. The writer made a little deal with him once and of course “got stuck.’” A quiet, almost inaudible, word from his wife, who evidently did not approve of his methods, seemed to have vitalized his conscience much to my advantage.

Always ready-witted and unabashed, he acquitted himself very creditably on the Highland pipes at a great gathering of the Hibernian and Caledonian Gaels in Central Music Hall a generation ago, when the program needed new life. His rendering of Irish tunes on the Scotch instrument left nothing to be desired on that occasion.

As we have stated, trading was his ruling passion, and in supplying pipe fittings he dealt with those at a distance as well as those nearer home. One day Sergt. Early met him carrying a tanned sheepskin under his arm. Being asked what he was going to do with it he answered, “Oh. A Highland piper up in Wisconsin wants it for a new bag.”

“But sure a porous thing like that isn't suitable for the purpose,” protested the sergeant; “ ‘tis too leaky.”

“Arrah, man alive.” answered Noonan, complacently, “them Scotch fellows could fill a sieve !”

Keen as Noonan was in effecting a sale, and oblivious as he appears to have been to the restraints imposed by the Decalogue, he was the soul of hospitality once negotiations were concluded, and he would cheerfully spend the profits with the purchaser.

As an agent or promoter under modern commercial conditions, “Pat” Noonan would be simply irresistible, and though his transactions may savor of sharp dealing, his subsequent liberality goes far to show that he was simply yielding to a natural propensity. A “good fellow” as the world goes, he out no inconsiderable figure in his sphere, but as was to be expected, he enjoyed neither riches nor long life.

DUNCAN MCDOUGALL

When our cherished friend, Joseph Cant, was approached on the subject of introducing his likeness in this work as a representative Highland piper. With characteristic unselfishness he exclaimed. “It you are going to put any Hielander in your book, Frank, tak Duncan McDougall, for he deserves it more nor any one.” Then the generous “Joe” went on to tell about McDougall's celebrity. Not alone as a piper and pipemaker, but as a typical, proud Hielander, who “wadna tak off his bonnet till no man” - no, not even royalty itself.

Much as his independent spirit appealed to Mr. Cant, we have good reasons for believing that the story of his dismissal on that account is somewhat apocryphal. For the leading facts in his career we are indebted to an esteemed brother Gael, the versatile Lieut. John McLennan of Edinburgh.

Duncan McDougall, a piper and pipemaker of the first rank, was horn in the city of Perth, in the shire of that name, in central Scotland, where his forefathers for at least five generations were pipers and pipemakers. He was piper to several gentlemen before his tame gained him the coveted position of piper to the Prince of Wales, afterwards Edward VII. His fall from royal favor was due rather to an excess of conviviality than to a lack of conventional courtesy.

A performer so distinguished could command his choice of engagements. For several years thereafter he served as piper to the Marquis of Breadalbane, but tiring of routine and restraint, both irksome to a man of his temperament, he bade adieu to nobility and took up the ancestral profession of pipemaking at Aberfeldy.

He did not long survive the change. For the path of fame as well as glory leads but to the grave. And he died in 1898, a comparatively young man. In his prime he won many prizes-gold and silver medals, dirks, powder horns, and valuable sets of bagpipes. A glance at his picture will be more enlightening as to his acquisitions in this respect than pages of description. Flattery and frailty are the penalties of fame.

WILLIAM WALSH

An ardent Revivalist who practiced what he preached in the furtherance of Irish regeneration, in all that constitutes distinct nationality, as persistently as did the subject of this sketch, is entitled to a place in our gallery of worthies.

William Walsh was born in 1859, at Oughterard, on the banks of Lough Corrib, County Galway, and, although coming to America with his parents in childhood, he is a fluent speaker and reader of the Irish language, and few are so well versed in the history and lore of his native land.

Self-taught in music, as in most other things, he took up the study of the Highland pipes when but little more than a boy. So zealous was he in his practice that the present writer has seen him lay down his dinner pail on returning home from work and, without waiting to change his begrimed clothing, put on the pipes and play while his mother was preparing supper. Wye may as well admit, however, that the neighbors were by no means unanimous in their approval of his tireless assiduity.

It would be but natural to suppose that, after listening for months to the mellow music of “Jimmy” O'Brien’s Union pipes, young Walsh would favor the Irish instrument, but he didn’t. Provided with suitable music, he learned to play by note and eventually to write music according to the Scottish scale, but not a little of his inspiration came from his frequent visits to William McLean, Joseph Cant, and some others, all famous performers on the Highland bagpipes.

Liberal, even lavish, with his music, he was the most obliging of men, and his only lapse into professionalism was a season's engagement with Sells Brothers’ circus in 1881. This of course was long before his connection with the Chicago police force, which commenced in 1891. Timidity or bashfulness being entirely foreign to his nature, he makes the acquaintance of every Scotch piper who comes to town, and it is owing to his energy and promptness in this respect that he induced no less than seven of them, on short notice, to enter the contests at the Gaelic Feis held at Chicago in July, 1912, and by the same token the prize winners happened to be only casual visitors in the city.

On that occasion, by the advice of the present writer, Walsh dismantled one of his tenor drones, thereby converting his set of Highland pipes into an Irish warpipe. This metamorphosed instrument served for all, but Walsh easily won the gold medal, the silver trophy being awarded to Walter Kilday. This triumph he repeated in 1913. The second prize was won by James Adamson.

Officer Walsh attends all Scotch picnics as a conservator of the peace, and although he does not compete in the piping contests, often acting as one of the judges, it would indeed be a queer day that he wouldn’t take a whirl at them for an hour or two; and whether it be on account of the excellence of his execution, or partiality for the Irish tunes which he plays, he is sure to have a large and appreciative audience.

Possibly with a view to finding an additional vent for his versatility, “Willy” learned to play the flute-by note, of course, for he scorns ear players. Dividing honors with the best of them for the gold medal at the Gaelic Feis before mentioned is no slight testimony to his proficiency. He was equally successful at the great Feis in Comiskey Park in 1913, tying for first honors with Charles Doyle.

The triumphs above set forth, though notable, do not constitute our hero’s chief claim to fame. In these days of costly living, William Walsh supports on a policeman’s salary a family of fifteen. Thirteen of his fourteen children are living. Oh! what a boon men like Walsh would be to a decadent nation like France, in which the births barely equal the deaths.