CHAPTER XXV

THE IRISH FIDDLER

Across the strings his bow he lightly draws,

And from the vibrant violin

A Voice speaks out, a timid plaintive voice,

So soft so sweet, so sad, that in

My heart I feel a restless, half-formed joy

That is to pain akin.

It seems as though the erstwhile silent soul

Had found a voice in which to tell

Its inmost dreams; it Seems as though the heart

Had found an outlet, in the swell

Of solemn sound that weaves upon the air

Enchantment 's wizard spell.

And like the music of the violin

Is life; sometimes a jarring strain

Will mar the harmony of joyous chords,

And yet discordance may be gain;

For pleasure, when we find it doubly sweet,

Comes in the wake of pain.

- Scannell O'Neill

Everything connected with him is agreeable, pleasant, jolly. All his anecdotes, songs, jokes, stories, and secrets, bring us back from the pressure of cares of life to those happy days and nights when the heart was as light as the heel. And both beat time to the exhilarating sound of his fiddle. His art was a key to the mansions of the rich and great, where his enchanting strains opened the pockets of the men and the hearts of the women.

The only instrument that can be said to rival it is the Union pipes, for which there is in fact a more lasting sentiment. Still the fiddle is, in the minds of many, the instrument of all others most essential to the enjoyment of an Irishman.

Dancing and love are by no means antagonistic, and the thrilling tones of the fiddle are never heard without awakening the most agreeable emotions. Its music, soft, sweet, and cheerful, acts like a charm on a susceptible nature. In the language of the great novelist before mentioned, “It opens all the sluices of his heart, puts vigor in his veins, gives honey to a tongue that was, heaven knows, sufficiently sweet without it, and gifts him with a pair of feather heels that Mercury might envy; and, to crown all, endows him, while pleading his cause in a quiet corner, with a fertility of invention and an easy unembarrassed assurance which nothing can surpass.”

Victims of the same misfortune, blind fiddlers were far less numerous than sightless pipers, for the quaint, plaintive tones of the old-style Union pipes - much below concert pitch - more potent and persuasive in their appeal to Irish nature than the crisp yet insinuating voice of the fiddle.

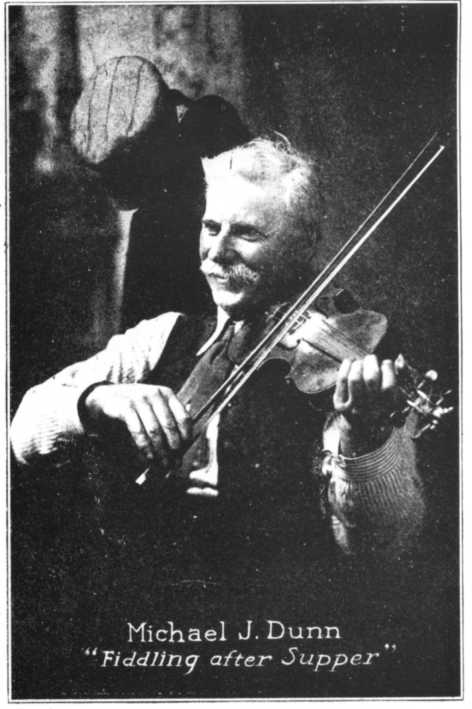

It must be borne in mind, however, that the fiddle was the favorite instrument of those who loved music for its own sake, and indulged their melodic fancies at pleasure, whether among friends in the community or in their own domestic circle, as suggested in the illustration.

FIDDLING AFTER SUPPER

"I love to play the fiddle

Nearly any time o` day.

When I'm feeling in the notion

And my fiddle wants to play;

But it's nicer after supper,

When the day's work's done. yon know.

And my thoughts get solemncholy

And I play right soft and low.

"Then the fiddle seems to join in,

Like your sweetheart at the gate,

When you're courting in the evening

And stay out a little late;

And my heart it gets to chording

With the music in the strings,

And the fiddle gets a-trembling.

And kind o' sobs and sings.

“Then my eyes they get to leaking,

And my voice don't want to speak,

And I feel so awful happy,

And so kind o' mild and meek,

That I love the whole creation,

As I play and walk the floor,

And just crave to own a billion,

So I might help the poor.

"And I most forgot to mention

That my little daughter, Nell,

Plays the chords upon the organ-

And you bet she plays them well,

And most always after supper

We just haves jubilee,

And I get as close to heaven

As a fellow needs to be!

"For my wife she'll sit a-smiling,

And the baby'll jump and coo,

And I feel so good and happy

That I don't know what to do;

And old `Nancy' and the puppies, ~

They think the music's fine,

For they all stand in the entry

And wag their tails and whine!

"Now you've heard the simple story

Of the music in me bred,

And I guess 'most everybody

Will smile at what I've said;

But I tell you there's no happiness

Like the kind a fiddle brings

When it trembles on your bosom

And just kind o' sobs and sings!”

The music of the fiddle has a wonderful hold on the affections of the people of West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, many of whom are the descendants of Irish settlers of the eighteenth century. Even in the state of Indiana the “Old Fiddlers’ Contests,” held annually and lasting several days, are among the most interesting events of the year.

Who has not heard of “Fiddling Bob” Taylor of Tennessee, who fiddled himself into the House of Representatives at Washington, then into the Governor's chair of his native state, and finally into the United States Senate. In default of money and influential friends in his campaign against a distinguished lawyer and politician in 1878, he tucked his fiddle under his arm and set out to win votes with its melodious strains, and he Won. Equally successful was he in the campaign for the Governorship, his opponent in that instance being his own brother, Alfred A. Taylor. Music proved more persuasive than oratory, for it entered the hearts of his audience, while eloquence passed over their heads.

As the sailor to his ship, the sportsman to his gun, so is the fiddler to his instrument, whose tones range from the bass of me resounding drum upward through a chain of a thousand modulations, to the shrill chirrup of the piccolo.

Seemingly simple and uniform in construction, fiddles possess marked individuality, and need we wonder then that, after years of association and manipulation and tuneful accord, the sightless owner affectionately endows his fiddle with personality, and a pet name.

"Old violin, sweet friend and love.

The world is dark; we're growing old;

The light is vanishing above;

No more I see your strings of gold.

The love--knots which our Ellen tied

Around your carved neck long ago

'Have faded in the friendless tide

Of summer heat and winter snow.

Old violin.

Dear violin,

Companion of my wanderings.

Your golden moans.

Your plaintive tones.

Plume memory with radiant wings.

"The sunny holds throw which wove strayed,

The woods wove sought from sun and rain,

The pebbled brook and chestnut glade,

Like blessed phantoms till my brain.

Out welcomes, as with set of sun.

From purple heaths and hills forlorn,

The villagers with labor done

Come dancing thro' the yellow corn.

Old violin,

Dear violin,

Once more like laughter touch my cars.

Once more arise

And fall my eyes

With floods of unavailing tears.

"How often in those olden times,

When shadows folded all the east,

And the ivied chapel's pious chimes

Tolled sweetly for the rural feast,

Have you and I in happy trance.

O'er green held from the dusty road,

Seen the brown groups of harvest dance

Till brows were red and ringlets flowed!

Old violin,

Dear violin,

Even now, with blinded eyes, I see

The roses red

That twined your head.

The brown ale foaming at my knee.

“Solace of my decining life,

Heaven blessed us with tranquility,

In all the moods of peace and Strife.

No pair could more contented be.

We left the monarchs crowned above,

To act their wise or foolish parts,

And with our strains inspired by love

Ruled the great universe of hearts.

Old violin,

Dear violin,

Tho` fame and fortune could not last,

We have no fears

For coming years

And no repentings for the past."

When Charles II had come to the throne, one of his first acts, we are told, was the bringing over to England of a band of twenty-four fiddlers. Each a prodigy in his way, but immeasurably inferior to their leader Baltzar. This man performed such marvels on the four slender strings of the violin that an honest gentleman of the period suggested his identity with Satan and seriously examined his feet in the expectation of finding them cloven.

Miracles of execution even on one string no longer excite our astonishment. For musicians have reached such a state of mechanical perfection that nothing more is to be expected along that line. And while their music may interest the cultivated ear it seldom touches the heart. We all know that the quaint and simple melodies of many tunes will commend them to those for whom an artless air has many charms.

The Irish Fiddler, it may be said, is in a class by himself. His music, whether plaintive or spirited, is freely sprinkled with graces, trills, and turns that give to Irish music its peculiar distinctiveness. And though his execution - often original and wayward - may be the despair of the trained violinist, who among the best performers can compare with him in touching the susceptibilities of his audience? How delightfully Hugh F. Blunt expresses these ideas in his poem :

AN IRISH TUNE

Will you listen to the laugh of it.

Gushing from the fiddle;

More's the fun in half of it

Than e'en an Irish riddle.

Sure, it's not a fiddler's bow

That's making sport so merry;

It's just the fairies laughing so-

I heard them oft in Kerry.

Will you listen to the step of it.

Faith, that tune's a daisy;

Just the very leap of it

Would make the feet unaisy.

Hold your tongues, ye noisy rogues,

And stop your giddy prancing;

It's me can hear the weeshee brogues

Of Irish fairies dancing.

Will you listen to the tune of it,

Sweeter than the honey.

I'd rather hear the croon of it

Than get a miser's money.

Sure, my son. it makes me cry-

But don't play any other;

May God be with the days gone by

I danced it with your mother.

Who but an Irish fiddler would think of taking part in an eight-hand reel, and dance to his own music “gushing from the fiddle? Yet an instance of that kind Was witnessed by the writer in his boyhood days in the commodious kitchen of a neighboring farmer. Great as has been the decline of peasant music and pastime since those days. We find that the feat is still in favor, for Mr. Hourigan of Bansha, Tipperary, is reported to have “brought down the house” at a Cork concert in 1912 by a similar performance. Many excellent performers among the traditional musicians had but a very nebulous conception of the value of musical signatures. Their execution, however, was instinctively correct as to tone, and it was only when they undertook to write music that their shortcomings in this respect were betrayed.

The witchery of the violin is not easily explained. In Music and Morals, Rev. H. R. Haweis says:

“I have never been able to class violins with other instruments. They seem to possess a quality and character of their own. Indeed, it is difficult to contemplate a fine old violin without something like awe; to think of the scenes it has passed through long before we were born, and the triumphs it will win long after we are dead; to think of the numbers who have played on it and loved it as a kind of second soul of their own; of all who have been thrilled by its sensitive vibrations; the great works of genius which have found it a willing interpreter; the brilliant festivals it has celebrated; the solitary hour it has beguiled; the pure and exalted emotions it has been kindling, for perhaps two hundred years; and then to reflect upon its comparative indestructibility. Organs are broken up, their pipes are redistributed, and their identity destroyed; horns are battered and broken, and get out of date; flutes have undergone all kinds of modifications; clarionets are things of yesterday; harps warp and rot; piano-fortes are essentially short-lived; but the sturdy violin outlasts them all. If it gets cracked, you can glue it up; if it gets bruised, you can patch it almost without injury; you can take it to pieces from time to time, strengthen and put it together again, and even if it gets smashed, it can often be repaired without losing its individuality, and not infrequently comes home from the workshop better than ever, and prepared to take a new lease of life for at least ninety-nine years.”