CHAPTER XXVI

SKETCHES OF SOME FAMOUS FIDDLERS

MICHAEL MCROREY

IN a character sketch from the facile pen of William Carleton, in 1840. the novelist pays his respects to 'Mickey' McRorey. A blind fiddler whom he had known in his boyhood days: “In my native parish (Clogher, County of Tyrone) there were tour or five fiddlers, all good in their way,” he says, “but the Paganini of the district was the far-famed 'Mickey' McRorey. He had no settled residence, for he was not at home once in twelve months, being “a kind of a here-and-therian -a stranger nowhere.”

Blind from infancy, a victim of smallpox, he possessed an intelligent countenance on which beamed that singular expression of inward serenity so peculiar to the blind. His temper was sweet and even, but capable of rising through the buoyancy of his own humor to at high pitch of exhilaration and enjoyment.

To be his guide or carry his fiddle case was an honor much coveted by the youngsters, and Carleton tells of his delirious joy in being the favored one entrusted with that responsibility for seven years when “Mickey” came around. His reception was cordial and vociferous, and, as the saying goes. “they near killed him with Kindness.” “Blood alive, Mickey, you're welcome”, “How is every bone of you, Mickey?” “Bedad, we gave you up.” “Ah, Mickey, won't you sing that song for us?” “To be sure he will. But wait till he gets home, and gets his dinner first.” “`Mickey', give me the fiddle case, won't you ?” “Aisy, boys, aisy, my fiddle hasn't been well lately and can’t bear to be carried by any one barrin’ myself.”

When “Mickey” was playing for a dance merry banter was always in order, and, blind though he was, his remarks on the performance of the dancers were so apt and humorous that he caused no end of merriment.

“Ah, Jack, you could do it wanst, and can still. You have a kick in you yet.” “Why, `Mickey,’ I seen dancing in my time,” the old man would reply, his brow relaxed by a remnant of his former pride, “but you see the breath isn't what it used to be wid me when l could dance the `Baltiorum Jig’ on the bottom of a ten-gallon cask. Sure I thought my dancing days were over.”

“Bedad, an’ you war matched, anyhow,” rejoined the fiddler, “Molchy carried as light a heel as ever you did; sorra woman of her years I ever seen could `cut the buckle’ wid her. You would know the tune on her feet still. Come now, sit down, Jack, till I give you your ould favorite, the `Cannie Sugach.’”

But it was in the dance house that `Mickey,’ was in all his glory. Scattering his jokes about, and so correct and well trained was his ear that he could frequently name the young man who danced by the peculiarity of his step.

“Ah, ha! `Paddy’ Brien, you’re there; I’d know the sound of your smoothin irons anywhere. Is it thrue, `Paddy,’ that you wor sint down to Errigle Keerogue to kill the clocks for `Dan’ McMahon? But nabocklesh! 'Paddy' what'll you have?”

“Is that Grace Reilly on the flure? Faix, avourneen. You can do it; divil o’ your likes I see anywhere. I’ll lay my fiddle to a penny trump that you could dance your own namesake, `The Colleen dhas dhoun,' the [bonnie brown girl] upon a spider’s cobweb widout breakin’ it. Don't be in a hurry, Grace dear, to tie the knot; I'll wait for you.,’

Poor “Mickey” was always playing jokes on the boys, such as asking them to bring him a candle, or getting them to lead him out on account of the night being dark or something equally absurd for a man who was stone blind. He was a professional fiddler when Carleton made his acquaintance about the year 1805, and, if alive, was an old man when immortalized by the great novelist.

JOHN MOOREHEAD

The subject of this sketch, who flourished in the latter half of the eighteenth century, was a native of the County of Armagh. His father, like “Piper” Jackson and “Parson” Stirling, was a violinist and piper of distinction, one of his pupils on the latter instrument being William Kennedy, a noted blind piper of Tanderagee, in the same county.

More famous than his father, John Moorehead won renown as a violinist and composer, and a place among the musical celebrities of the kingdom. It is recorded that he was violinist at the Worcester Festival of 1794, and afterwards played the viola in the orchestra of Sadler's Wells Theatre, London, in which his brother Alexander was leader. In 1708 he was violinist of Covent Garden Theatre and composed music for the above named and other theatres.

The adage that genius is akin to insanity has been well exemplified in this family, for both brothers became insane in middle life. Alexander died in a lunatic asylum at Liverpool in 1803, and John committed suicide by hanging a year later.

Among the latter's musical compositions, according to British Musical Biography, was `Speed the Plough' - a famous country dance, written in 1799, whose sparkling strains have retained their popularity undiminished to the present day. Though regarded as an English tune from the fact of its being first heard in English theatres, it is decidedly Irish in character, and much as we have been disposed to include it in the Dance Music of Ireland its alleged English origin effectively repressed the desire.

This delightful folktune germinated in the brain of an Irishman after all, and we are no longer barred from claiming it as our own.

PATRICK COUGHLAN

A native of Crossmalina, County Mayo, had at great reputation as a traditional fiddler in that part of the country. He must have been born about the beginning of the nineteenth century, for he was apparently beyond the scriptural age of seventy years when John McFadden knew him in his boyhood. He played with a free, sweeping bow and, notwithstanding his advanced years, this fine old musician - a type now, alas, very rare - maintained himself in comfort at the local dances and “patrons,” which in those days dispelled the monotony of peasant life in poor, persecuted Ireland. I

PETER KENNEDY

A worthy successor to Hugh O’Bierne, the famous fiddler of Ballinamore, County Leitrim, elsewhere alluded to, was Peter Kennedy, a farmer who lived a few miles out of town. Born about 1830, he is said to have had no superior in his day in the county, and we can well believe it, judging from the settings of his tunes which we have heard members of his family in Chicago play so delightfully.

Perhaps nothing better illustrates the fascinating influence of his music than the following: In the year 1895, Mr. John Gillan of Chicago embarked for a European trip, accompanied by his wife and son, Rev. John Gillan. While visiting the old home in the adjacent county of Longford Mr. Gillan heard of Mr. Kennedy’s great reputation as a fiddler. Ever and always enthusiastic about the music of his native land, he made up his mind to call and not miss such an opportunity. So charmed was he by Mr. Kennedy’s performance that he decided to remain in that vicinity instead of proceeding with his family to Rome, according to the original programme. Under their father's training, four of his children - Thomas, Frances, James, and Ellen became fine fiddlers. From personal knowledge We can testify that

JAMES KENNEDY

was a sweet, expressive fiddler, and, as far as time and tone are concerned, he left nothing to be desired. Almost as interesting as his music was the tuning and testing of his instrument. The combination of chords which he brought out in varied and rapid succession before attempting a tune convinced one that his teacher was a master of his art.

A farmer’s son, born in the early sixties of the last century, he came to America to better his fortune, but did not follow music as a profession. Many of his tunes hitherto unpublished - and he never played a poor one - were noted down and printed in O’Neill’s Music of Ireland and The Dance Music of Ireland. Of course those tunes, as well as others obtained from his sister Ellen, were learned from their father. A trip to the old home in the winter of 1912 revealed a deplorable state of affairs as far as music was concerned. There were neither fiddlers nor fiddles of any consequence. The spirit of emulation was dead, and not a fiddle of the Perry, or other valuable make, was left in the community. They had been quietly picked up for a few pounds each by speculators.

Since the disintegration of the Irish Music Club some years ago James Kennedy, now a park policeman, seldom swings the bow.

HUGH O'BIERNE

Away back in the early years of the nineteenth century there flourished a famous fiddler of the above name at Ballinamore, County Leitrim. Evidently overlooked by Dr. Petrie, he was encountered by William Forde, the noted Cork musician and collector of Irish airs in his travels. The meeting was turned to good account, for the latter availed himself of the stores of knowledge and musical skill which the generous minstrel placed at his service.

Speaking of the latter, when the Feis Ceoil authorities selected some of his contributions for publication, Dr. P. W. Joyce said: “O’Bierne belonged to a type of country musician to be found sixty or eighty years ago all over Ireland, full of love and enthusiasm for Irish music. But the type has all but vanished, for although there are still musicians, professional and amateur, thinly scattered throughout the country, they have, generally speaking, neither the skill nor the taste nor the knowledge of their predecessors.”

JOHN SALTS

Among the many famous fiddlers who flourished around the middle of the nineteenth century in the southern part of County Leitrim and the contiguous territory of the County Roscommon, John Salts was deservedly prominent. He was not only a fine musician but an expert dancer, and, being a man of attractive personality, his popularity knew no limitation in that part of the country.

No less renowned as a fiddle player was his teacher

“MUDIN” CHALK

whose profession was in a sense the result of necessity. In his infancy a hungry sow strolled into the house in search of provender and finding the baby sprawling on the floor, chewed off the fingers of the right hand before his mother could rescue him. Thus bereft of lingers, the bow had to be strapped on to his maimed hand and, notwithstanding this handicap, Chalk became famous for his music and execution.

The nickname “Mudin” (pronounced Moodheen) which eclipsed completely his Christian name, means in the Irish language “little hand without fingers.” It will be remembered that the Irish have at all times been noted for the aptness of their descriptive nicknames and topography.

BRYAN SWEENEY

A professional blind fiddler, hailing from Esker, near Mohill, County Leitrim, was said to be unexcelled in his day, according to Mr. Peter Kennedy of Ballinamore, a celebrated player himself. He owned a valuable Perry fiddle for which he was offered a hundred pounds. The poor blind minstrel a year or so later stumbled and fell on the instrument and smashed it beyond repair.

MICHAEL ROONEY

A professional fiddler of Ballina, County Mayo, bore a great reputation for skill and execution in his circuit in that and the adjoining County of Sligo. He was about 35 years of age when Mr. Gillan heard him in 1850. Rooney enjoyed all his faculties unimpaired.

Another famous fiddler of the same generation known as

“BLIND” KERNAN

taught a noted fiddle player named Kennedy of Drumlisk, County Longford, and Terence Smith, now of Chicago. Many a pleasant hour Mr. Gillan spent listening to Kernan’s music in 1850, when he played at the “Red Cow’, tavern, a mile distant from the town of Longford.

MARTIN ROACH

To most persons the mention of Kilrush brings to memory the second largest town in the county of Clare and it may be of interest to state that there are no less than five places so named in the Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. The Kilrush in which we are interested in this instance is a parish in the barony of Scarawalsh, County Wexford, the same in which Martin Roach, a fiddler of distinction, was born. Roach was a personal friend and sporting companion of Samuel Rowsome, the celebrated farmer-piper, and his pupil George Carroll, who was considered to be the best resident piper of Wexford outside ot the Rowsome family.

Martin Roach, who died in 1881, is still remembered as a first class traditional fiddle player, and as fine a specimen of Irish manhood as was to be found in that part of the country. Standing six feet two inches in his vamps, of perfect proportions, his handsome appearance and genial disposition went a long way to enhance his popularity as at musician. He had been taught by a poor demented migrant fiddler from Galway named Lynch, nicknamed “The Cove,” a soubriquet he delighted in. Eccentric, but harmless, the latter fortified himself with all the accessories of his calling, such as tuning forks and scientific appliances for testing the tension of his fiddle strings, etc. Another of his foibles was the purchase of cheap music books of every conceivable kind, a practice in which he spent the greater part of his scant earnings.

DANIEL SULLIVAN

Everybody in Boston and the adjoining towns, and not a few from other parts of this broad land, knew or heard of “Dan,’ Sullivan, the great Irish fiddler, who departed this life at the end of June, 1912. Though an octogenarian, he was game to the last. A few days before his death he asked his son and namesake to accompany him on the piano while he played a few of his favorite tunes. Realizing that the end was near, he calmly announced that he would be dead soon, but that there was one man left in Boston who could play Irish music, and that was “Bill” Hanafin, his cherished friend and companion for twenty-three rears.

The old minstrel’s ancestors were of the Kerry stock, but his father being a traveling tradesman, won the heart of a charming colleen at Millstreet. County of Cork, and it was in that town the subject of our sketch was born. After the family had moved to Tralee, young `Dan', studied music under the Whelans, so renowned in their day, but spent much of his early manhood in the northern part of the county enjoying the company and example of “Mike” Hurley, a celebrated blind fiddler of those days.

While in a reminiscent mood one evening at Boston, the amiable old minstrel told his friend Hanafin how he came to lose the first fiddle he had ever owned. He was on his way one Sunday night to Hurley’s house at Derrymore, west of Tralee, after playing all the afternoon for a country dance about three miles on the other side of Tralee. Meeting an ass on the road, and being by that time footsore and weary, he congratulated himself on his luck. The donkey, accustomed to ill usage, submitted patiently enough to “ Dan’s” getting on its back. But as for traveling - why, that was quite another matter. A liberal application of a branch of thorny furze which the rider managed to secure promptly overcame his reluctance, and he started off at rattling pace. With his fiddle under his arm, “Dan” straightened up proudly at the success of his expedient when the ass stopped as suddenly as a man who had forgotten his ticket, and the jockey continued a few yards further but landed on his head in the middle of the road. When the stellar display faded and “Dan” had partially recovered his senses, he groped around for his fiddle; but, alas! he found not a fiddle hut a little bag of kindling wood, splintered beyond repair.

Twenty years of Mr. Sullivan's mature life were passed in London where he acquired some musical knowledge at the hands of a certain major. A brief visit to Ireland preceded his coming to America where he remained to the end of his days the most famous professional Irish fiddler in the eastern states.

No one possessed a greater store of ancient Irish airs for he was born and brought up in the midst of tradition and, true instinctive musician that he was, nothing of genuine worth ever escaped his receptive ear. His style of rendering plaintive melodies was extremely florid and involved, and though commendably liberal with his music generally, his choice selections were treasured for his friends.

Learning in Chicago of Mr. Sullivan's great abilities from “Patsy” Touhey, the noted Irish-American piper, the writer paid him a visit in 1905. Like “Paddy” Coneely, the Galway piper, who, according to Dr. Petrie, was overanxious to display his skill on quadrilles and polkas, Mr. Sullivan insisted on playing concertos for our edification instead of the old Irish melodies we hungered for. Not only was he a teacher but a maker of violins, and like a child with at new toy he lectured us enthusiastically on the scale and capability of a new pipe chanter that he was just learning to manipulate. He was then 75 years old and, from his point of view, entertained us right royally. Still, were the programme one of our own choosing, the result would have been much more satisfactory.

JEREMIAH BREEN

The subject of this sketch hailed from the parish of Ballyconry between Listowell and Ballybunnian, County Kerry. Having lost his sight early in life, music was his only recourse, and as he had talent in that line he became an excellent fiddle player.

Besides playing at Sunday “patrons,’ with “Tom” Carthy, the centenarian piper of Ballybunnian, Breen made money teaching his art to farmers’ sons and playing at Saturday night dances which were by no means uncommon in those days.

Among his pupils was Michael Kissane, a business man of Chicago, well known as one of the best Irish fiddlers in the City. Altogether Breen may be considered one of the most successful and prosperous of his class in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

MAURICE CARMODY

In many ways the most noted of Jeremiah Breens pupils was Maurice Carmody, a prosperous farmer near Listowell. County Kerry.

A perfect Adonis in looks and stature, he was no less fluent on the fiddle than supple as a dancer. His company was coveted and no man was better fitted than he to contribute to or enjoy the pleasures and pastimes of the Munster peasantry. Born in 1862, his love of music and sport found convenient opportunities for their indulgence, and from early youth Carmody was conspicuously identified with all local festivities. Richard Sullivan, an exceptionally clever dancer of the traditional style, was one of his boon companions in former days around Listowell.

DENIS SHEEHAN

Quite noted for his proficiency around the middle of the nineteenth century was Denis Sheehan, a professional fiddler of Abbeyfeale, County Limerick. He taught many pupils in that part of the country and was connected with a flourishing dancing school also.

MICHEAL HOGAN

One of the celebrated Hogan family of musicians of Cashel Tipperary; Michael, the second oldest of the live brothers, became a violinist. Although the members of the family who elected to play the Union pipes - the real national instrument - became famous, little is known of those who chose the fiddle as their favorite instrument.

A fiddle player of the first class, according to our best information, Michael Hogan lived and died, and left a family at Thurles. His younger brother

LARRY HOGAN

who is a traveling fiddler, sustains the family reputation for musical excellence. No further intelligence concerning him is available at this writing, except what may be found in the sketch of his father, Michael Hogan, in the chapter on famous pipers.

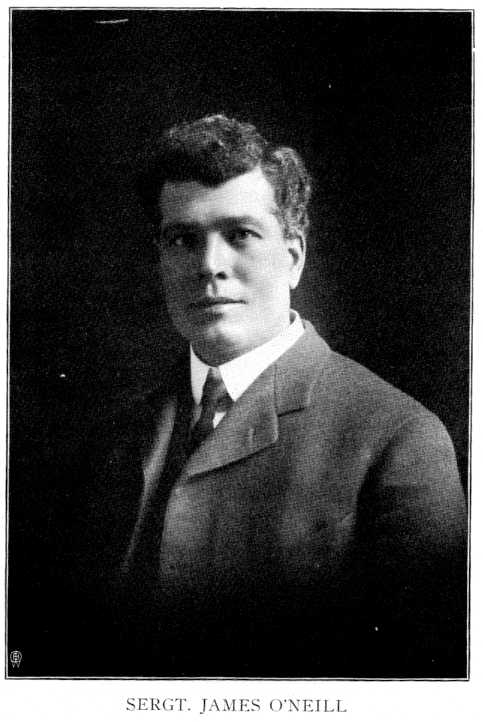

MICHAEL MCCORMICK

No fiddle player whose tame has been sounded in the “Land of the West” was so supreme in the art of rendering traditional Irish music, according to his Kings County friends. As Michael McCormick of Tullamore. His playing was the standard of excellence by which all violinists were judged, and to their disadvantage invariably, as the following instance will show: One evening Sergt. James O’Neill, who noted down from the playing of others much of the music in the O'Neill Collections, was playing some slashing tunes in concert with Bernard Delaney, the celebrated piper, in the latter’s parlor. After cutting loose on as few rounds of a particularly captivating reel, the sergeant, with a countenance lighted up with triumph, swung around to the audience as if inviting merited applause. Before the others could utter a word of approval, “Jack” Doolin, not at all enthused over the performance, yelled out “Oh, `Barney,’ you ought to hear McCormick play that. He was the boy that could put the right edge on it.”

And so it was in every case. “Did you ever hear McCormick ?” has become a byword among the “craft,” for according to his “townies” McCormick stood unrivaled. His father James, who taught him, was blind, and though an excellent fiddler was excelled by his son.

Both were professionals and played at the races at Mullingar and other places as well as at the ordinary festivities common to all parts of the country. Michael the “Nonpareil” died in 1909 at the scriptural age of three score and ten years.

PATRICK WHELAN

A man like Mr. Whelan of Scarawalsh Ballycarney, Ferns, County Wexford, is a priceless acquisition in any community. Sincere, helpful, and talented, his presence is an inspiration, and to his influence may be traced much of the activity of the music revival movement in that part of the country. Passionately devoted to music himself, he has been a missionary among those musically inclined, traveling long distances and unselfishly imparting his musical knowledge without fee or reward, other than the consciousness of well-doing, and the pride which is his due when his proteges and pupils like the De Lacy family band become noted prize winners. He was born near Bree, some five miles southwest of Enniscorthy, County Wexford, in 1862. and learned very early in life to play some airs on the flute from John Breen. He joined the Bree Total Abstinence Fife and Drum Band when organized by Father Scallan in 1879. A year later he bought a fiddle and enrolled as one of James Sinnott’s pupils. So clever was young Whelan on the flute that he played at the crossroads dances at Ballyhogue, and being equally precocious on the fiddle he was soon playing in concert with his teacher in public. In fact his progress was so rapid that in a short time he took Sinnott's place in playing for mummers and the subsequent dance when the weather was unfavorable or the teacher was disinclined to travel. But perhaps the reader would like to hear from Mr. Whelan himself.

“I was a born lover of native Irish melody, and as my memory extends over a period of forty years I have been a sorrowful witness of its decay almost to extinction-supplanted by a spiritless substitute scarcely deserving the name of music in any degree of comparison with our own beloved strains. Often have I entertained a kind of sorrowing hope that it would in some unaccountable way be preserved from oblivion to which it was fast being consigned; yet I never expected to see my hopes so fully realized as in the publication of your magnificent collections.”

We will have to pass over Mr. Whelan's laudation of the present writer’s contributions to the cause as being too personal, and pick up the thread of his correspondence further along. Speaking of O’Neill’s Music of Ireland: “It is my dearest possession; it never palls, never tires. I read, recite, for it is in itself a language - and rehearse with fiddle or bagpipe or flageolet, day in and day out, only to find I can never indulge the passion to satiety.

“Going through the pages listlessly, my eyes rest upon the first classified reel, `The Girl Who Broke My Heart’. The act re-awakens the celestial strains of `Jemmy’ Sinnott’s fiddle, although the hand that produced them has lain for thirty years in the grave. When I turn to the `Irish Music Club’, or `Cronin’s Favorite Reel’, `Jem’ Cash, that prince of Irish pipers, is again in the flesh and I am in his presence, and my eyes with tears are wet. I often peruse the pages so intently and so long that when I close the book I see the characters reproduced upon the wall, and as thoughts will come unbidden I sometimes wonder if any of the great composers caught their inspiration in this way. Anon I find the names of the tunes grouping with additional words and short phrases forming word pictures like the following: `Big Dan O’Mahony’ took the `Blackthorn Stick’ to `Smash the Windows' of the `Church of Dromore’ because the `Minister’s Daughter’ played `Hide and Go Seek’ `Behind the Haystack’ with `Johnny I Hardly Knew You.’ “

Only extracts from Mr. Whelan’s interesting but lengthy communications can find space in a work of this nature, but as music revival is our present subject, a glimpse of its practical results will not be amiss.

“`Tom’ Mulligan, one of my earliest pupils, a wealthy farmer and fine specimen of Irish manhood, delights in giving lessons at his own house to all likely aspirants, two of whom have attained local distinction by their performances at public and parish concerts. `Tom’ himself always shunned the limelight, although he might be fairly taken as an abridged edition of your Edward Cronin. He was one of the best of reel players. The music broke upon the ear in waves, and with a passionate vehemence as if impatient of being so long pent up in a fiddle. I suppose this comes of the native gift of being able to lay on the accent properly. With a hand firm and strong he drew a volume of tone out of the instrument such as I have not yet heard any to equal, even the best of our `tramp’ fiddlers.

“The repose of his countenance while playing and the absence of muscular motion, save of his forearm and fingers, was truly phenomenal. We now live some ten miles apart, but Mulligan is still to the good, and doing service in his own unostentatious way to the beloved cause of traditional Irish music.

“`Pat’ Breen, a schoolmate and companion, although he did not learn to play the fiddle until past 25, became a most versatile fiddler, playing not only jigs, reels, and hornpipes, but all kinds of tunes and melodies. He could read and memorize music by sight or hearing equally well, and then transcribe the same accurately.

“For a farmer of brawny muscle his delicacy of touch was no less wonderful than his faculty for the absolutely correct apportionment of time, even in the very quickest movement. And those were only half his qualifications, for in rendering an accompaniment to a singer or in solo, as an exponent of song air he had no compeer beneath the professional rank. He infused his renderings of national songs, whether vocal or instrumental, with the true soul of music.”

Alas, for the attainments and virtues of our most cherished friends! Death, which loves a shining mark and is no respecter of persons, beckoned the gifted Breen to eternity in the year 1906.

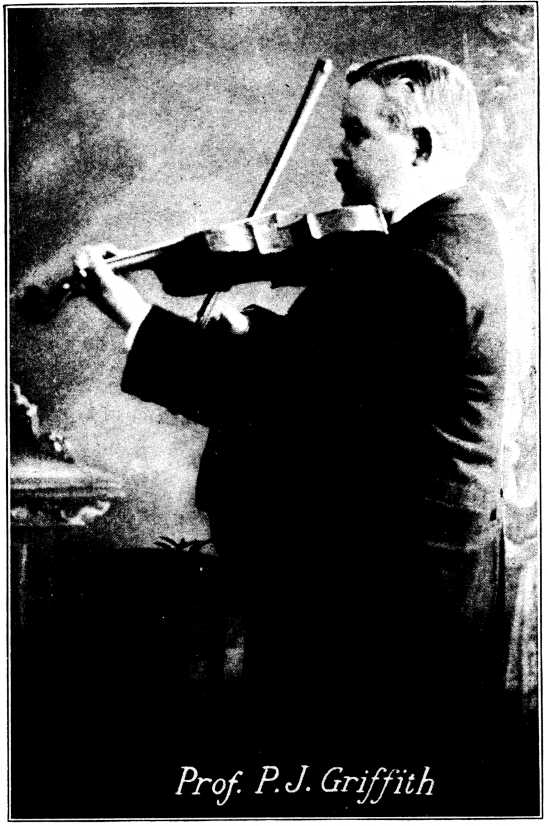

Mr. Whelan writes interestingly of the Ross and Ormonde families to whom music is an inheritance as well as an acquirement, and of several youthful enthusiasm in making, mending, and playing musical instruments; but, as before stated, the De Lacy family band or “Musical Nine” are his special pride. A glance at the picture of the group will he more instructive than a page of description.

In closing our sketch of this shining exemplar in a cherished cause perhaps an extract from a postscript to his latest letter may not be inappropriate.

“P. S. Often when out from home or going on a journey l find diversion in calling to mind the names of tunes in the following or similar manner until I can remember every one in the book.

“The `One-horned Cow’. after browsing in the `Garden of Daisies' and destroying half the `Blooming Meadows’ the `Night before Larry was Stretched’ whipped the `Old Plaid Shawl’ and `Jackson's Frieze Coat', from off the `Tinware Lass' and 'Spellan, The Fiddler’ when they lay among the `Turkeys in the Straw’. Not yet subdued, she hooked the `Ladies Pantalettes’ from the `Yellow Leg' of the `Maid in the Cherry Tree’, ate the `New Apron' on the `Dark Girl Dressed in Blue', chewed `Paddy Hagerty’s Leather Breeches’ and licked the nap off `Jerry's Beaver Hat’, in which he wore the `White Cockade’ at the `Siege of Troy’ and the `Battle of Aughrim' and the `Downfall of Paris’. “

Regretfully we must take leave of the versatile Patrick Whelan and leave to conjecture the fate which befell the one-horned bovine guerilla after her career of rapacity and rambunctiousness.

JAMES SINNOTT

No name stands out more prominently among the noted minstrels and musicians of central Wexford in the late generations than that of James Sinnott.

Born in the year 1800, at the village of Bree (some ten miles south of Enniscorthy). where his patents kept a general store, young Sinnott’s life was dedicated to music. Afflicted with defective vision from birth, he was placed at a very early age under the tuition of a celebrated Irish fiddler named Curran, “whose fame has been forgotten,” in the language of Mr. Patrick Whelan, our correspondent, “and whose biography has been left unwritten - a fate shared by many a deserving genius of the Irish race in this and other periods of our national history. Jemmy Sinnott was a precocious youngster for it is reported that when but nine years old he fiddled for the entertainment of customers. He readily mastered the rudiments of music and acquired a knowledge of the principles of harmony and composition, and was looked up to as an authority on musical history, especially those features relating to the origin and development of musical instruments.

A man of fine physique – strong and athletic - he was unrivaled in his profession, and being also exemplary in his habits, we can well believe that none could boast of greater popularity in the community. In wit and sarcasm like the bard O'Carolan he was equally keen, but the latter gift was sparingly displayed except under provocation.

One night at a party a youth was presented to him as a musical prodigy by his admiring friends. `Jemmy’, with the his sightless orbs directed straight at the embryo Paganini, handed him his fiddle and said abruptly “Oh man anouns! Play something.” The young fellow, unprepared for this turn of affairs, blushed to the roots of his hair, but timidly taking the proffered instrument, played a tune as best he could, and returning it, stood modestly awaiting the approbation which he felt his effort deserved.

“And, my boy, what name do you call that tune yon were playing?” quizzically inquired the professor.

“ `The Girl I Left Behind Me,’ sir,” replied the prodigy in the flush of his fancied success.

“Oh, then, that was the girl who had the good luck in store the day you turned your back upon her?’” was the crushing remark of his questioner.

The great musician didn’t always have the best of it, however.

“Arrah where are you going now, Darby?” he once asked a “gaum” or simpleton.

“No place” was the gruff answer.

“And whereabouts is no place, Darby?” continued Sinnott.

“Shut your eyes and you'll see.’, was the startling response of the “gaum” to the man of music, thus illustrating the old Irish proverb which reckoned a fool’s reply as one of the sharpest things in existence.

As an accompanist to traditional singing, “Jemmy” Sinnott enjoyed a great reputation. For his knowledge of folk songs and the airs to which they were adapted was phenomenal.

As a professional fiddler his circuit did not extend beyond a day’s journey, but within the compass of his travels he was a veritable musical missionary. He played at barn dances, social gatherings, weddings, christenings and other festivities, and this mode of life he continued unremittingly up to within one year of his death, which occurred in January, 1884. Though defective in sight from birth, he had not become totally blind until late in life.

With a sweeping bow he phrased the melody or tune according to his fancy- staccato or legato - and in his masterly execution the most simple tune realized unexpected possibilities. The exuberance of graces skillfully interwoven into the texture of the theme left nothing to be desired in the way of traditional embellishment. “The gorgeous coloring imparted to his renderings,” says Mr. Whelan. “still dwells in the memory of those who once heard, and refuses to be forgotten even after the lapse of years.”

No less famous as a teacher than as a performer, Sinnott is said to have taught more “scholars” than any other man of his class in Ireland. Among his most distunguished pupils were Edward Evoy, Knockstown; Patrick Cummins, Raheenduff; Thomas Canning and John J. Evoy of Adamstown; Peter Moran, a farmer of the parish of Glynn ; Thomas Asple, of Galbally, County Councilor, an enthusiastic revivalist; Thomas Asple. His cousin: Patrick O’Brien, District Councilor, Hayestown, Taghmon; Philip Cogley, Galbally; Denis Whelan, of Scarawash, Bree; Christopher Maddock, of Glynn; Moses O’Brien, of Wilkinstown, Taghmon; Paul Roche, Bridgetown; and Thomas Freeman, New Ross. His last pupils were Martin and Patrick Whelan of Scarawalsh, the latter being authority for the leading features in the career of the talented and much esteemed musician.

For the last twenty-five years of his life Sinnott lived as a squatter in a little house to which there were two small gardens attached, and which he enjoyed as a free holding on the top of Raheenahone, Burren mountain. Becoming afflicted with cancer on his lower lip in his eightieth year, he had a presentiment that it had come for his death as both his father and grandfather had died at that age. However, he bravely underwent a surgical operation and survived it four years; and Mr. Whelan assures us that having never before been so long separated from his beloved riddle; their reunion was a thrilling experience.

No music, ancient or modern, came amiss to Sinnott, and he could cater to any company, “gentle or simple,” for his mind was a musical treasury. Great as was his reputation, he magnanimously acknowledged a master - one Patrick Quinn of Enniscorthy, whose brilliant career was prematurely ended some sixty years ago. He walked off the quay at Enniscorthy one dark and stormy night, and as the river Slaney was in flood at the time, the incomparable Quinn was drowned.

As the clay fell on the coffin enclosing the mortal remains of “Jemmy” Sinnott on a cold morning in January, 1884, his sorrowing friends and pupils could not help regretting the treasures of melody and music lore which passed away with him beyond recovery.

THOMAS MULLIGAN

Not only is Thomas Mulligan - one of “Jemmy” Sinnott’s pupils-a famous fiddler, but he is also engaged in the musical “uplift.” He was born in 1869, and is a prosperous farmer at Garrenstacle, Bree; County Wexford. In connection with the Bree Dramatic Class, recently organized, Mulligan became the leader of an orchestra consisting of five fiddles, two concert flutes and a piccolo.

Three of his pupils - Joseph O'Donahue, Thomas Mernach, and James Sinnott, with a young prodigy named Patrick Clancy - swing the bow, while the chief manipulator of the flutes is Martin Byrne, a prize winner in his line.

The boys of Wexford, it seems, are still to the forefront in all that pertains to Irish nationality.

SERGT. BERNARD KELLY

It is surprising how many fine musicians are to be found among the Irish constabulary who, owing to the peculiar conditions and sentiments heretofore existing in Ireland, were doomed, like the flowers of the forest, to waste their sweetness on the desert air of the barrack room. The Royal Irish Constabulary band of Dublin, by the way, is one of the most noted in the kingdom. In America, where all officers of the law are citizens and voters and reside with their families promiscuously in the community and are rather looked up to then otherwise, members of the police force are not objects of prejudice either in private or public life. Being neither constables nor employes of an unpopular government, the American police are peace officers of the State and Municipality and therefore men of standing in the commonwealth.

At a popular demonstration at Ferns, County Wexford, a few years ago, so many bands from the surrounding country attended that the De Lacy Warpipe band were crowded into the police barrack while processions and functions of a solemn and religious character were being conducted. The presence of the De Lacy band naturally attracted people from the street. Influenced, no doubt, by the musical atmosphere, one constable took down his fiddle - one of extraordinary tonal qualities - and rattled off “The Bush in Bloom,” “The Harvest Home’, and “The Star of Munster.”

So inspiring was the example that Sergt. Kelly, a native of Queen’s county, came in and took down his fiddle, which had hung up unused since the death of his wife two years before, and started to play. And play he did in grand style and tone when he warmed up to it.

“Playing by note” he regarded as a matter of minor importance once the tune had been acquired. Unconscious that he was drawing a “full house” as the strains of his melody floated through the open doors into the highway, the Irishman beneath the king's livery broke loose from the trammels of officialdom and he reveled in the delights of traditional melody until he found to his dismay on looking around that he was playing to a spellbound audience, among them being his live subordinates and four or five constables from other stations.

Laying down the fiddle, Sergt. Kelly, in real alarm, shouted to his force “Get out, every one of you! Here you all are and not a man in the town if anything happens.” Before he could use his cane they had vanished with alacrity.

As a fiddler of the traditional stamp, the sergeant was a “rouser,)’ and being kindly and forbearing, he enjoyed a popularity by no means common to his calling. Now retired on pension, his keen sense of humor, so noticeable among instinctively musical people, and his tuneful fiddle, will, it is to be hoped, render the sunset years of his life pleasant and enjoyable.

PATRICK DUNNE

When it became publicly known a dozen years ago that some practical steps had been taken towards the preservation of Irish folk tunes in Chicago. One of the first to communicate with the writer on the subject was Patrick Dunne, a Tipperary farmer, of Kilbraugh, the Commons parish of Ballingarry, not far from Thurles. Not only was his sympathetic encouragement an inspiration, but the pages of manuscript music which he unselfishly forwarded proved that kindred spirits in every hobby can be found the world over and that the vastness of Ireland's musical remains can hardly be overestimated.

Mr. Dunne’s musical training on the fiddle was obtained from the Morrises of Ballysloe, and splendid fiddlers they were in the opinion of their famous pupil. Following the footsteps of so many of their class, the whole family - father, four sons and two daughters - emigrated to America in the early seventies, where their profession is not looked upon with disfavor.

We can well imagine what cheer and jollity a man of Mr. Dunne’s temperament and talent can promote in any community with his fiddle; and even though burdened with a farmer’s responsibilities, he found time to attend Feiseanna at Kilkenny, Waterford and Carrick-on-Suir, and capture first prizes at each of the musical competitions.

Regretfully he admits, while nearing the three score milestone in the highway of life, that the outlook for the revival of Irish music is not all that could be desired, for there is but little incentive and less example to stimulate or foster its study and practice.

WILLIAM HENNESSY

Round about the year 1863 a strikingly handsome young fiddle player named William Hennessy happened along to the parish of Ballingarry, barony of Sliev-ardagh, County Tipperary. He was about thirty years of age, over six feet tall and soldierly in his bearing; but his personal attractions were not a circumstance to the fascination of his music. Like the pipers of old who were said to have been kidnapped by the fairies, Hennessy could not get away from his admirers.

So many were anxious to learn from him that he was prevailed on to remain and teach. In the language of our friend, Mr. Patrick Dunne of Kilbraugh, “they made a god of him.” Not a few of his pupils made rapid progress and gave promise of future fame, when Hennessy’s eyesight began to fail and he was obliged to become an inmate of the Urlingford Union or Infirmary, where he died in 1867.

His parents, a respectable old couple, came to the parish after their son’s death. The father, who was a much less distinguished performer than his son, proved a very capable teacher. The associations were too painful, however, and they left after a short stay, presumably for Cork, their native county.

The suspicion that William Hennessy had military training proved correct for it developed that he had served as bandmaster in the army for a time.

THE HIGGINS BROTHERS

of Killkenny whose parents, long since dead, hailed from Killenaule. County Tipperary, are said to rank among the best in their profession in Leinster, at least in this generation.

MICHAEL HIGGINS

One of the trio is a traveling fiddler of whom no other information is available at this writing.

JAMES HIGGINS

lives in the town of Kilkenny and has an interesting family, all musicians, while

THOMAS HIGGINS

who is reputed to have had few equals, is said to be suffering from the effects of a specialized brand of Irish hospitality.

According to Rev. Dr. Henebry, “Tom” Higgins. A famous fiddler and descendant of fiddlers and musicians, “is the last representative of Irish professionalism in music.” Born in Kilkenny and taught by his father, he often played in concert with James Cash of Wicklow, whose performance on the Union pipes proved so fascinating to the fair sex. Higgins had a phenomenal bow hand, and his peculiar emphatic “sweeps” gave his reels an indescribable charm. His reverence never saw anything to equal the pliancy of his wrist and consequent command of the bow.

In all that tends to promote the regeneration of Irish ideals in music and dancing, language and literature, among the “Exiles of Erin” at the Antipodes no one is more persistent, potent, and practical, than Patrick O’Leary of Eastwood, Parkside, Adelaide, South Australia.

Endowed with an attractive personality and gifted with uncommon musical attainments, his correspondence proclaims him a writer of no ordinary ability. And were his lofty sentiments and patriotic ardor shared by any considerable portion of his countrymen. Ireland would not be regarded as it is by some - a spot on the map, or a term in geography,

In every movement designed for the rehabilitation of the old land, Mr. O’l.eary's name figures conspicuously as organizer, chairman, and even entertainer; for being a fine violinist of the old school, and playing in concert with his no less talented son Eugene on the piano, their joint performance is a rare musical treat.

Phonograph records of Mr. O’Leary’s fiddle-playing which we enjoyed at the home of his brother Owen, and sister, Mrs. Kelsey, in Chicago, justify any eulogy which our words could express.

Though his surname is suggestive of Munster origin, the subject of our sketch hails from Benwilt, Drumgoon, near Cootehill, in the county of Cavan, where he was born in 1851. Race suicide found no favor in those days evidently, for Patrick was the youngest in at family of seven sons and five daughters. Before emigrating to Australia in 1876 he had spent a few uneventful years in the United States. From an humble position in that far oft land he has risen to that of head attendant of Mental Hospital, Parkside, Arlelaide, an office of responsibility and emolument.

His letters to The Anglo-Celt of his native county in the interests of the Gaelic Revival should be an inspiration to the “Old Folks at Home’, from an expatriated Irishman.

Speaking of those who engage in the “uplift” in any line of undertaking, he says: “The bravest, best, noblest, and most gifted have been assailed, misrepresented and maligned by those for whom they have struggled, labored and died, and it seems to be their lot to feel the pangs of hostility and ingratitude from quarters whence it was least expected or deserved.” This bit of moralizing is but the reflex of a transitory reminiscence, and he passes on to tell of more cheerful things: “I had the pleasure of playing that grand old reel, `Kiss the Maid Behind the Barrel.’ on the City Hall stage on St. Patrick’s night, 1905. It was tastefully sanced by four strapping young lads and received a flattering ovation. My son accompanied me on the piano and I was delighted it went off so well.”

With the death of John Coughlan, they were left without an Irish piper in that part of Australia at least. So the “progressives,” with Mr. O’Leary at their head, set about introducing the Warpipes, or its later development, the Brian Boru pipes. An appeal through the press for funds to all lovers of Irish music brought them one hundred and sixty pounds sterling, and nine young men began to learn, not under the instruction of a piper, mind you, (for they had none) but a clarinet player and bandmaster. Eugene O’Leary being the Honorable Secretary to the club, there is no lack of enthusiasm.

Many years ago Mr. O’Leary endeavored to obtain a set of Union pipes - the perfected Irish instrument - from an aged piper named Kelly who used to wander about the country, but his efforts were unsuccessful, as the old minstrel had disappeared and finally died in some institution. At one of the meetings of the Band Committee an old man strolled into the room carrying an old faded and worn bag under his arm, and sat beside Mr. O’Leary. “What have I in the bag, eh? Wisha sure, ‘tis only an ould set of Union pipes.” His questioner promptly assisted him in dragging forth the ancient instrument, the tones of which had haunted him since boyhood days. “Och sure they’re no good to me. I got them from poor ould Kelly before he died, but I can't play 'em at all.” For ten shillings Mr. O'Leary gained possession of his long-sought treasure after nearly twenty years of fruitless search. Without reeds and in a state of delapidation the old minstrel's instrument was taken home in triumph but remained out of commission for a long time, there being no one capable of putting it in order, until an Englishman - a Northumbrian piper - happened along one day and undertook the job.

The newcomer had a beautiful instrument on which he could play jigs and hornpipes quite well, and in rendering the border minstrelsy of both England and Scotland his performance left little to be desired.

The big drone of the Northumberland small pipes which Mr. O’Leary describes, was only twelve inches long, the other four drones being smaller in proportion. The tone is sweet and pleasing. They are, in fact, a replica of the Irish Union pipes with the exception of the chanter which has fourteen keys and is permanently stopped at the bottom.

“The Northumbrian pipes go well with the fiddle,” Mr. O’Leary continues, “and we are able to play very well together owing to the fact that I had spent some years learning Scotch dance music and melodies.

All movements in pursuit of an object either political, social, or musical, are, of course, much discussed by those interested, and more or less valuable information is obtained, often from unexpected sources and out-of-the-way places. The discovery of an Irish piper through a correspondent in the Murray River country, some seventy or eighty miles back from Adelaide, was a rare find indeed. So Mr. O’Leary lost no time in communicating with the backwoods minstrel, Mr. Critchley by name. Nothing loth, the latter promptly accepted the invitation to come to the city, where suitable arrangements were made to have an Irish night at the “Catholic Club” on his arrival.

To attempt to edit Mr. O’Leary’s account of subsequent events, and the tumultuous emotions which thronged his breast, would be little short of sacrilege, so we will let the patriotic exile tell the story himself:

I will now try and explain to you my thoughts, feelings, and emotions on hearing and seeing the Union pipes played after a lapse of forty-one years - from 1869 to 1910.

As the time for the piper’s arrival drew near I sauntered to the railway depot to meet him, and as I trudged along, Keegan’s beautiful lines,

One winter’s day, long, long ago

When I was a little fellow,

A piper Wandered to our door

Grey-headed, blind and yellow,

occurred to my memory, and I mentally recited the verses until I arrived at the depot where I discovered “Caoch” awaiting me.- I brought him home in triumph, and he drew forth the long wished for Union pipes, and also a set of Brian Boru warpipes which he had ordered from Melbourne some time before. But the gay and gaudy warpipes had no charm for me as compared with the ancient, much~worn and loved Union pipes. A mist came over my eyes, an uncontrollable rush of feelings and emotions almost shook my very soul. Delight, sorrow, sad memories of the long ago, the old home, the old scenes, the old barn, poor old Phil Goodman the piper, the innocent gay and light-hearted lads and lasses that were assembled on the last night, forty-one years ago, flashed across my mental vision. I could not speak, I tried to pull myself together while I examined the well loved instrument that had so often filled my boyish heart and soul with delight while vainly trying to quell the torrent that was choking me.

Piper Critchley tuned up and commenced to play while I sat with bowed head listening to the well-remembered, soft and pleading strains. I seized my fiddle, tuned up with the chanter, and fixing that glorious book, O’Neill's Music of Ireland, before me, I bade farewell to Australia.

My spirit took wing and I passed-

Over islands and continents;

The wide oeean's main-

Soon sighted Cape Clear

On my soul’s aeroplane;

Soon viewed the loved haunts,

With my heart throbs and tears,

And caressed the loved ones

Through the vista of years;

Saw the shadowy forms,

Through dim dawn of day,

Of the dear ones I loved,

Long since turn’d to clay.

We passed over beauteous Munster to the “Banks of the Ilen,’ and “Tralibane Bridge,” where we paid a heartful homage to the spot that gave you birth.

Soon I renewed my acquaintance with the loves of my youth, the peerless “Miss Monaghan,” “Bonnie Kate,” “Miss Thornton,” “The Dark-haired Lass,” and “The Merry Sisters,” all fresh, fair, beautiful, and enchanting as when I first heard them. “The Bucks of Oranmore,” “Buckley’s Fancy,” and “The Bush in Bloom,” then engaged our fancy until we had “A Cup of Tea” with “Drowsy Maggie’, and “The Dublin Lasses” while awaiting “Corney’s Coming.” We next visited “Peter Street” and the beautiful “Bank of Ireland,” and afterwards dwelt long and lovingly on “The Dublin Reel.” On the way to “Mooncoin,” we picked up the ever green and always beautiful “Ivy Leaf,” after which we enjoyed ourselves “Rolling on the Ryegrass.’, The piper then invited me to help him “Toss the Feathers.” This we did with a vim and then indulged in a long interview with “The Scholar” fresh from “Salamanca,” also “Lord Gordon,” with his friends, “Col. Fraser” and “Col. McBain,” accompanied by the beautiful “Miss Wallace” and the “Fermoy Lasses.” To this delightful company we bade a reluctant farewell, toasting their healths in “A Flowing Bowl,” and mounting the “New Mailcoach,” we arrived in time for “The Fox Chase.” After a merry run, our attention was attracted to “The Boyne Hunt,” which brought us to the banks of the historic river where we met that beautiful but contentious nymph, who, when interviewed, emphatically declared that she was intensely Irish of the Irish - but she added, “like all good things in Ireland, I was seized by the invader and compelled to serve a vile purpose.” I felt the truth of her statement and assured her that the date was already visible to the clearsighted when her dishonorable occupation would be gone, and she would be restored to the honored position that her beauty and charm entitled her to.

During the colloquy I kept my eye on the piper just to see how he’d stand it. He wisely suggested that we had better try and “Kiss the Maid Behind the Barrel,” and this labor of love we accomplished with a fervor that left nothing to be desired.

Breathless after this pleasing incident, we engaged in the “Five Mile Chase,’* and soon arrived at the historic “Rock of Muff,” otherwise “The Star of Munster.” This wild, beautiful, and thrilling melody was a great favorite in Cavan, and was named after the high plateau-topped rock near Kingscourt, on which an annual Feis is held. We next indulged in a “Trip to the Cottage,” and started “Round the World for Sport,” incidentally calling on “My Love in America.” We lingered longingly in the famous Jackson’s everblooming “Flowery Garden” at Creeve, County Monaghan, and being but a few miles from Cootehill, courtesy suggested that we pay our respects to the distracted “Nell Flaherty” on the loss of her beautiful “Drake.”

From mirth to sadness is but a step. I realized when my eye caught a glimpse of the Lament for “Capt. O’Kane or the Wounded Hussar.” The hero of a hundred fights, from Landon to Oudenarde, who, when old and war-worn, tottered back from the Low Countries to his birthplace to die, and found himself not only a stranger, but an outlawed, disinherited, homeless wanderer in the ancient territory that his fathers ruled as Lords of Limavady. His friend and sympathizer, the illustrious Turlogh O’Carolan, has immortalized his name in strains the most plaintive and touching.

On the old racecourse of Cootehill and within a stone throw of the home of my father, I again met “Jack o'Lattan,” the product of the musical genius of the renowned “Piper” Jackson. In all directions could be seen “The Swallows Tail,” as well as the verdant corn and unmown hay waving gently with “The Wind that Shakes the Barley,” and crowding thickly round the dance circle were the dimly remembered forms and faces of the dancers of fifty years ago, long since passed into the unknown beyond. Full of sadness, my eyes fell on the “Shan Van Vocht” but a thrill of joy hashed through my brain as I recalled the prophetic utterance of O’Connell, for I know that a race now tread these plains,

With hot blood in their veins,

Who will burst her galling chains-

A hand was laid softly on my shoulder: I looked up. It was my good wife, who reminded me that tea had been ready for some time. This recalled me from the past to the present and I found myself back in Australia. A glance at my watch showed that the piper and I had played without intermission from one to six-thirty o’clock that afternoon, so we laid away the fiddle and the pipes and “The Music of Ireland,” with mingled emotions of joy, sadness, and regret.

Oh God! How I sighed for one month with the O'Neills, Cronin, McFadden, Dillon, Delaney, Early, Enright, Kennedy, Ennis, Kerwin, etc., of the “Irish Music Club’, of Chicago, but alas, fate has decreed that, situated as I am on the opposite side of the globe, the joys of such companionship can never be mine.

Mr. Critchley inherited the pipes from his father, who was an accomplished player. He emigrated from his native Wicklow to Australia in 1849, and played around the diggings at Forest Creek, Ballarat, and Bendigo, in the early fifties, and the pipes certainly looked as if they had many and varied experiences. From long-continued fingering the chanter was deeply indented at the vents. The pipes were old ere their advent in Australia over sixty years ago. As they lay on the table, worn, faded, dingy, and dented, with one drone missing, a second reedless and mute, and a third twisted and bent by the fiere heat and varying temperature of sixty subtropieal summers, they reminded me of a once beautiful and world-famous prima donna shorn of her beauty, and glories forgotten, and impoverished, and all but dead.

Oh no; surely there are still devoted lovers left who will worship at the shrine of this beautiful and matchless interpreter of our incomparable Irish music. Surely, oh! Surely, that magnificent organization of Ireland’s choicest sons and daughters - The Gaelic League - will rescue and restore this famous stricken prima donna, who, neglected, forsaken, and alone, has sought shelter in obscure places to die. Surely they will raise up and place her in the proud position that she should occupy-the Prima Donna of Ireland’s Music.

There was a sadness almost tragic in those old and service-worn pipes. Where, Oh! Where, are the glad-hearted boys and girls who tripped gracefully and joyously to their strains. Seventy, eighty, perchance a hundred, years ago? God only knows. The unconquerable Michael Dwyer may have danced to their music on the day of his bridal,

When Mary came in her beauty,

The loveliest maid of Imael.

The sweetest bower that blossomed

In all the wild haunts of the vale.

Well, the piper slept soundly that night, and in the morning early I called him up-not to hear him play “The Wind that Shakes the Barley,” but to catch the early morning coach to his distant home on the banks of the lonely and legendless Murray, where the wild scream of the parrot, the raucous yell of the cockatoo, and the mocking shout of the laughing jackass, are the sole incentives to music.

My dear sir, I feel that I am wearying you with this almost interminable epistle, but you can recognize that when a man is full of a subject he rarely possesses that nice sense of discretion which warns him that it is time to leave off. I feel isolated as there are hardly any Irish musicians in Adelaide, and still fewer to whom I can unfold my thoughts and feelings on a subject so absorbing, so overpowering and, alas, so unsatisfied-always yearning for that which I cannot obtain - the fellowship of genuine Irish musicians.

I remain, dear sir, your most sincere and deeply grateful friend,

April 18, 1911. PATRICK O’LEARY.

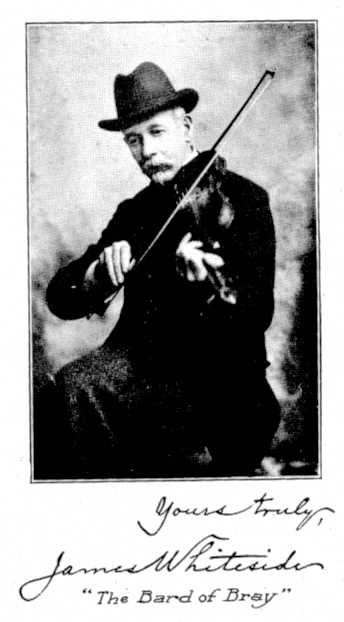

JAMES WHITESIDE (THE BARD or BRAY)

Who in this generation more faithfully typifies the bard of ancient days than James Whiteside of Bray, County Wicklow - scholar, poet, musician, and composer? Nothing, except perhaps a flowing beard, would improve the combination. Delicacy forbids us to mention the date of his birth, as he is still a bachelor, though confessedly wedded to art. But a quotation from his delightful correspondence epitomizes that story in language both candid and concise:

“I am an ex-National Teacher, having retired on pension after forty years' service, so I have plenty of time to devote to my favorite hobby – music. I have been awarded first prize on two occasions: at Oireachtas, 1903, and Feis Ceoil, 1906, for the best performance of Irish music on the violin; and I also play the Irish harp, Irish pipes, and piano, all of which I have in my room. I am the holder of a certificate for drawing also; so I must solace myself with painting, poetry, and music, never having been lucky enough to get a wife.” Mr. Whiteside being a handsome man, we must leave to conjecture the cause of his celibacy. After all, we may as well admit that the versatile hard was born in 1844, his place of birth being in the County Monaghan.

Did he not openly attribute his good health and exemption from ailments to the effects of total abstinence, we could well surmise his temperance tendencies from the opening lines of several of his original songs, he being the author of no less than two score of them. For instance:

“Sobriety is making way in the Ireland of today,”

“Fill the bumper fair, every drop is poison.”

“Will you walk into my parlor said the spider to the fly? ‘Tis the prettiest little drunkery that ever you did spy,” “O! Join the Abstainers, and you'll be the Gainers.” In his Anti-Emigration Song, what could be more poetic or pathetic than the cry of blended - alarm and regret -

“They are going, they are going, and a mother’s tears are flowing!”

One would scarcely expect to find such emotional phraseology as “O! My Colleen’s’ a Darling,” “My Darling Rose in Beauty Grows,” or “Our Honeymoon It Was in June,” in the diction of an incorrigible bachelor like “The Bard of Bray.” What could be prettier or more natural than “My Pretty Little Girl, Won't You Come Along with Me ?” as a name for a song when its author was but twenty years of age. Perhaps the coquettish little thing didn't respond, and her coldness fatally chilled the tender germs of love in a sensitive heart. Who knows?

Such a galaxy of songs - moral, sentimental, and patriotic - and such a selection of musical compositions, airs, dance tunes, and lullabies, has Mr. Whiteside produced that we know not which to admire most. It is gratifying to know that his genius is appreciated, for his patrons hail from near and far, including Scotland, England, and America.

“It was on the Hill of Howth, I believe, that Saint Patrick preached to the heathen Irish, converting them to Christianity” says a writer in The People of Dublin, August 14, 1910; “and it was here also, one Sunday afternoon, that I fell under the spell of an apostle of the temperance movement. A musical apostle he was, dressed in an evening suit, with a tall hat, and his breast bedizened with ribbons green and yellow - decorations and badges of which the meaning was beyond me. But his instrument was a fiddle, and he sang to the tune of it- not standing or sitting, but marching up and down with a swaggering air like a Highland piper. He had a fine, noble, and distinguished presence, had this Hill of Howth fiddler, and might have sat to a painter for the figure of an ancient bard. I only hope those bards of old could finger their strings as effectively as my apostolic friend on the Hill of Howth. Like Richard Wagner, he was the author of his own songs, and the one he was now treating me to was called `Pat of Enniscorthy,’ a very good song indeed, of the rousing, rattling kind, whereof the moral was the awful consequences of drink, and the evils which excessive indulgence in whiskey had entailed on `Poor Ould Ireland.'”

The bard whose mien and music so won the admiration of the Dublin writer was the subject of our sketch. James Whiteside.

With characteristic graciousness, he has submitted his manuscript collection of Irish music amounting to nearly 200 numbers, to Dr. P. W. Joyce of Dublin, who will include a selection therefrom in his next work.

An edifying Essay on Irish Music and Dancing, Accompaniments, etc., from the facile pen of our bard, we find, much to our regret, too comprehensive for our pages.

THOMAS FITZGERALD

Whether famous, fair, or farcical as performers, a large percentage of Irish minstrels for more than a generation, sad to relate, end their days in the Unions or poorhouses.

One of the last of them was “Tom” Fitzgerald, an exceptionally fine fiddler, who played around Dublin for years, and died in 1909 an inmate of the South Union, when less than fifty years old. Competent authorities claim that he had no equal in the city or vicinity as a traditional performer, yet he never sought honors at the Feis Ceoil Competitions.

A native of Tramore. County Waterford, “Tom” Fitzgerald was one of a family of fiddlers, and was taught by one “Jerry” Martin, the most renowned instrumentalist in that part of the country in his day.

In the words of one who heard him play at a Dublin concert or entertainment. “`Tom’ Fitzgerald, fiddler, was a revelation of traditional playing. He made the violin speak with the Irish voice.”

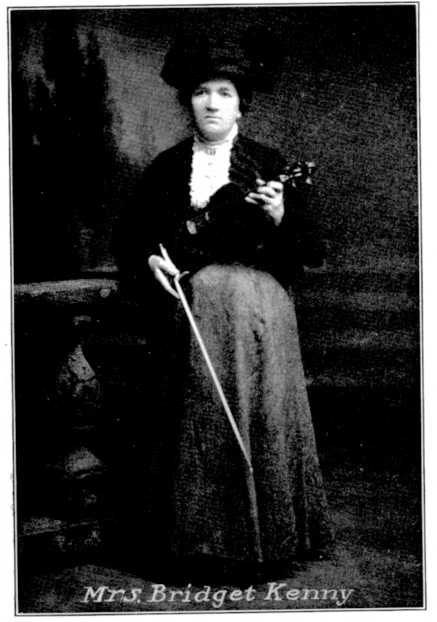

MRS. BRIDGET KENNY, “THE QUEEN OF IRISH FIDDLERS”

In no country save Ireland, would a violinist of such demonstrated ability as the subject of this sketch remain unappreciated and practically unnoticed, while obliged by necessity to contribute to the support of a large family by playing for a precarious pittance along the highways and byways of Dublin for a generation or more.

The Gaelic Revival brought Mrs. Kenny into the limelight, and after she had outclassed all competitors as a traditional violinist at the annual Feiseannah winning first prize year after year, she was proclaimed “The Queen of Irish Fiddlers.”

This remarkable woman's talents ought to have been regarded as a national asset. Yet it does not appear that any effort was made to take advantage of the opportunities presented by her discovery, by the establishment of a school in which the much-vaunted traditional style of rendering Irish music would be taught and perpetuated.

No. “The Queen of Irish Fiddlers” amid salvos of applause, was handed her first prize with monotonous regularity, and allowed to pass out and resume her daily perambulations as before, along the streets of the Irish capital, to woo the reluctant coin from purses often no less slender than her own.

The musical faculty, not wealth not station, was her inheritance as the daughter of John McDonough, the premier Irish piper of his day and generation, who passed away in obscuritv in his native County of Galway more than half a century ago, when little Bridget was less than two years old.

Artistic endowment is bound to find expression, and it is not surprising that this little child of genius should start to “play the fiddle” when but seven years of age. “I'm entirely self-taught, and I'm proud of it,” is the way she put it when asked how she came to have such wonderful control of her instrument, “and I've never been beaten in playing jigs, reels, or hornpipes, for the last forty years.” A sister, Mary Anne, and a brother, John McDonough, both now dead, were also fine fiddle players.

“Mrs. Kenny is a very excellent performer, the best I have heard,” a writer of discrimination reports. “She has a noticeable peculiarity in `stopping and bowing’ which is very quaint and attractive. About nine years ago I heard her for the first time in a bout of playing which lasted three hours. Three years ago I heard her again, and anything better than her rendering of the `Flogging Reel’ it is impossible to conceive. Her playing of airs pleases me not quite so well, but of course her circumstances precluded her from possessing a first-class instrument.”

Born and bred in an atmosphere of music and tradition, it was but natural that Bridget McDonough, the fiddler, glorying in her art and a luxuriance of auburn tresses which “sthreeled” on the ground, would favor the suit of John Kenny, a piper, who laid seige to her heart. United by more ties than one, they have since continued to play in concert for a livelihood.

Mr. Kenny, however, does not confine himself exclusively to the Irish pipes, for he can take a turn with equal facility on the bass viol, fiddle, dulcimer, and tambourine.

Their joint collection of unpublished Irish music has been awarded a prize on three different occasions.

Devotion to art does not appear to have unfavorably affected the size of Mrs. Kenny's family, for we are informed she is the prolific mother of thirteen children. Neither did the artistic temperament on both sides mar the domestic peace of the Kenny home, and, though the goddess of plenty slighted them in the distribution of her favors, have they not wealth in health and the parentage of a house full of rosy-cheeked song and daughters, several of whom bid fair to rival their mother, “The Queen of Irish Fiddlers,” in the world of music.

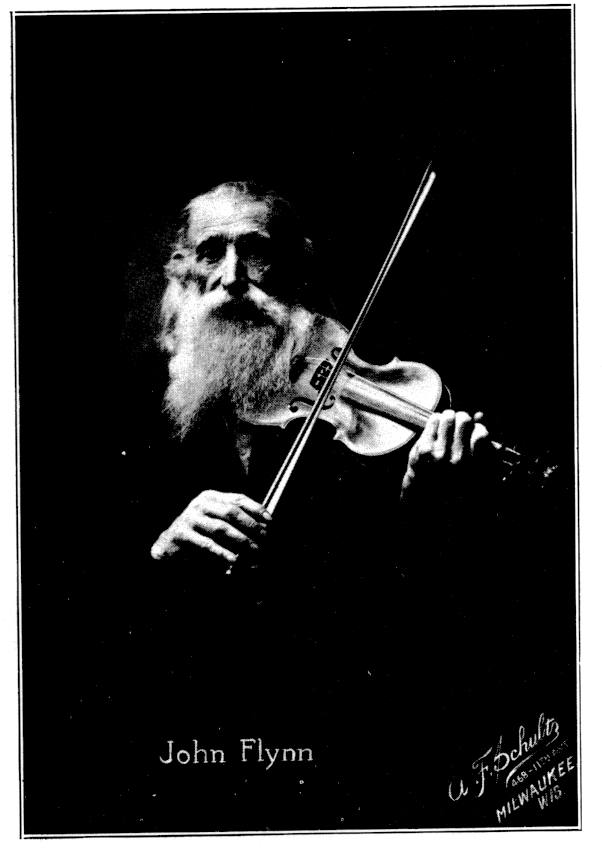

JOHN FLYNN

With a luxuriance of snow-white locks encircling his sturdy shoulders like a mantle, a patriarchal heard signifying a countenance both noble and placid, a Turveydrop in deportment, a Chesterfield in manners, and towering in stature - no bard of old could be more inspiring and impressive than John Flynn, the Bard of Erin, Wisconsin, whose likeness adorns our pages. Standing six feet three inches in his vamps, and erect in bearing as an Indian, a figure so remarkable could not fail to attract the attention of artists as a rare subject for their brush. Restrained by a modesty by no means characteristic of minstrels or musicians, of whom he is one of the most noteworthy, twice only has he been known to yield to importunities to pose for a picture, the last occasion being at the earnest solicitation of the writer in order to furnish a photo for the present work.

His parents, Timothy Flynn and Mary Wa1lace Flynn, were born near Mallow, in the County of Cork, Ireland, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and there was nothing of which Mr. Flynn was more proud than having attended school in his boyhood days with Thomas Davis, the poet-patriot, and John Baptist Purcell, who when but thirty-two years of age became bishop of Cincinnati.

Like President Andrew Jackson, our here, John Flynn, narrowly escaped being born an Irishman, for his parents had been in Massachusetts but a year or so at the time of his birth at Springfield in 1840.

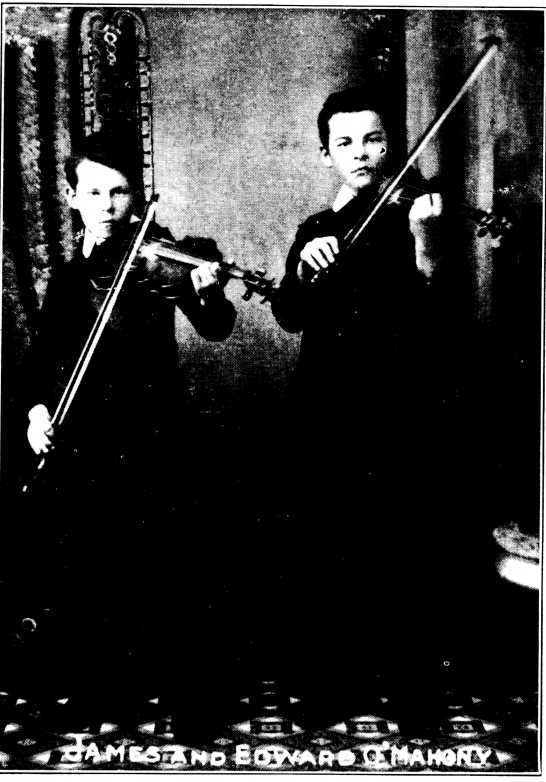

Having saved some money as foreman of a railroad gang. Mr. Flynn started for the west in 1843 and landed at Milwaukee, it being then little better than an Indian village. He settled on a farm in Erin township, Washington County, where the youngest son, James - also a fiddler - was born, beneath the shadows of Wisconsin's primeval forest. “In very early years we had a fiddle in the house -a cheap affair,” writes the subject of our sketch, “and James and I learned to tune it accurately by some means - I hardly remember how. We learned to play a few tunes with patience and perseverence by hearing them sung and lilted by our parents. My father, especially, knew an immense number of jigs, reels, and hornpipes, although he never played on any instrument.” The brothers were subsequently taught from written music by James Lynch, a Tipperary man, who was a fine musician, and they attended the Shamrock School in the town of Erin - the first district school organized in that part of the country.

His father desired that John should enter the University of Wisconsin at Madison, the state capital, but, being accustomed to the handling of tools since boyhood, and having learned the carpenter trade from his uncle, Michael Lynch, John preferred to engage in the building business.

While erecting churches, dwellings, and barns, in the country round about with his brother Denis, his fiddling circuit was equally extensive, and so he always kept in excellent practice and circulating the tunes he had learned from Lynch and his parents.

Seeking a wider held and better opportunities, he established himself in Milwaukee in 1883 and took up building and contracting on a larger scale, the Linden hotel being one of his undertakings.

It was the writer's good fortune to spend some pleasant hours in our friend Mr. Flynn’s company in April, 1911, at the home of Capt. M. J. Dunn of the Milwaukee Fire Department. He played the fiddle with great spirit and precision in concert with our host, and Sergt. Early of Chicago on the Union pipes. His performance, which was excellent, was less conspicuous than his modesty and the refinement of his manners, and while gazing in admiration if not awe at this unassuming yet splendid type of man, fluently fiddling the music of his Irish ancestors, though brought up in the backwoods, one could not help speculating as to what distinction might he not have attained had he graduated from the University of Wisconsin as his father had intended, instead of from the carpenter's bench in a pioneer settlement on the outskirts of civilization.

MARTIN CLANCY

It would appear that the race of household musicians is not yet extinct in Ireland. Here and there, from Waterford to Clare, and even in Wexford, pipers and fiddlers became attached to certain families as of yore, but it is evident that the underlying motive is not so much the perpetuation of old customs, as the inborn love of Irish music and sympathy for the musicians.

A fiddler of great repute named Martin Clancy has been brought to notice by our friend Patrick Powell of Tulla. County Clare. For years Clancy has been patronized by Hon. William Halpin of Newmarket-on-Fergus, an ardent revivalist, on account of his exceptional talents. Mr. Halpin's nephew, Frank O'Coffey, now connected with the Irish American of New York City, speaks very highly of Clancy's musical versatility. Now about seventy one years or age, he was born at or near Kilrush. Most famous as a fiddler, he has quite a few pupils, but he also plays the flute, Union pipes, and perhaps one or two other instruments. He is generally regarded in Clare and Limerick as without an equal, especially as an exponent of the traditional style. His rendering of “The Fox Chase,” “Taim im Chodhladh,” “Eamonn an Chniuc”, and other ancient pieces, has gained him much local renown. “Rocking the Cradle,” in which he mimics the crying of the baby, is another of his masterpieces.

Unfortunately the jovial Martin has his little eccentricities, like most famous musicians, the most pronounced being his free use of the fiddle to enforce domestic discipline while in his Bacchanalian moods. Though but little of the original instrument remains, as a result of frequent repairs, the temperamental Martin's veneration for it is unfaltering. He talks to it as if it had been endowed with life, and sleeps with it snugly reposing under his pillow.

PATRICK CLANCY

Great as is the reputation of Martin Clancy as a traditional fiddler on the banks of the broad-bosomed Shannon, it is no disparagement to his fame to say that, as an all-around performer on the violin, he is equaled by his son. Patrick Clancy, of New York City.

The only child of his parents, the latter was born in the sixties at the Limerick side of Thomond Bridge, near the barracks. Inheriting his father’s musical talent, he profited also by his training, as the sequel proved. Clancy’s orchestra, of which he is the leader, is in much demand at Irish balls and entertainments, and competent authorities assert that as an Irish performer on the violin he is unequaled in that city. The son, too, has his peculiarities. He fills his engagements scrupulously and to the minute - but no more. That is simply business without sentiment. Yet, when the ball is over he will visit some bartender friend and roll out jigs and reels for him until morning.

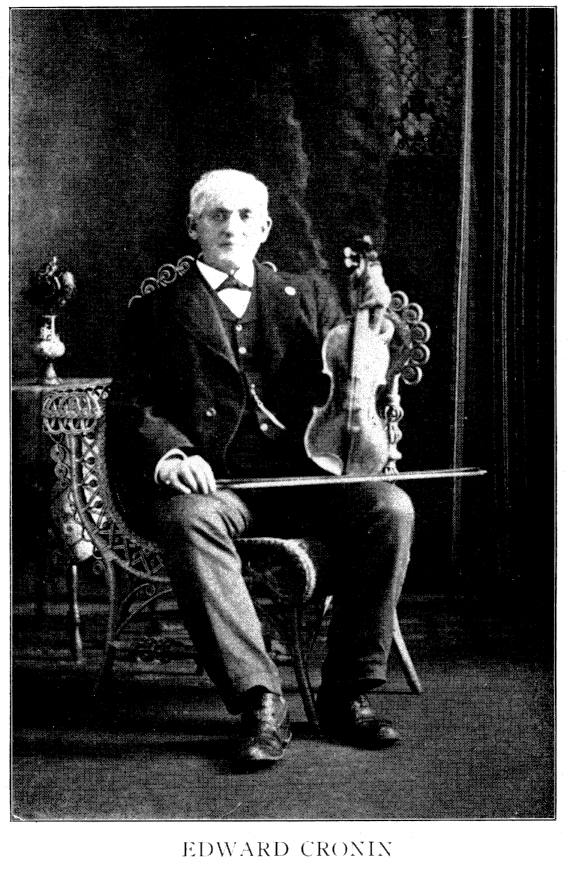

EDWARD CRONIN

Of more ancient vintage than any of the prominent traditional fiddlers of Chicago at the beginning of the twentieth century, was Mr. Cronin, a native of Limerick junction, in County Tipperary. He was born about 1838, and when little more than a boy was in great demand to play odd tunes and Long dances for expert dancers because he certainly had talent as well as training. If we mistake not, he was taught by one Ryan, whose insatiable love of music was such that, after playing for a dance all night, he would play for his own pleasure along the road on his way home in the early hours of the morning.

A weaver by trade, Edward Cronin finding no demand for his craft on arriving at Troy, New York, has followed any line of employment available ever since. Blest - or shall we say cursed - with the artistic temperament to excess, this remarkable man enjoyed but a few brief years of appreciation in Chicago subsequent to his chance discovery, although he had been a resident of the city for a long time previously. The proverbial failings of the musical fraternity were in his case intensified by a nature so suspicious and unrelenting that it was his open boast that he never forgot nor forgave an injury. And the worst of it was that the injury was more often fancied than real. Making all due allowance for his many good qualities, enduring friendship was unattainable, and more is the pity, for in the great western metropolis whose Irish population exceeds that of Dublin, Edward Cronin had but one rival as an all-around traditional fiddle player.

From long isolation he had forgotten most of his music, and owning almost as many fiddles as he had tunes, he changed from one to another when the tone did not suit him. Can we wonder at this seeming whim in view of the fact that his work, day after day for many years, had been grinding castings on an emery wheel at the Deering Harvester Works. How he played so well with such coarse and scarred fingers was little short of miraculous. Faultless in time and rhythm, he was liberal and obliging with his music when in the humor, and so well recognized were his abilities in this respect that even after he had severed his connection with the Irish Music Club he was engaged by its officials to play at the annual picnic for the stepdancers.

Mr. Cronin's memory proved a rich mine of traditional Irish melody, but it took years of cultivation and suggestion to rouse his dormant faculties to their limit. As this phase of the subject has been dealt with quite freely in Irish Folk Music, A Fascinating Hobby, its repetition here is unnecessary. Visits to his home were fraught with pleasure, especially when he played in concert with two young friends from Troy - Patrick Clancy on the flute and Thomas F. Kiley on the mandolin. Clancy, Mrs. Cronin's nephew, possessed a most wonderful voice, powerful and mellow, and to our unscientific ear the most delightful we had ever heard. On the violin the genial “Tom” Kiley swung the bow with a freedom which many professionals might envy. “The Connemara Fiddle,” as we facetiouslv termed the mandolin, was his favorite instrument, however. In playing Irish dance music he displayed a facility of execution almost inconceivable. To him “The Flogging Ree1,” a lively, three-part dance tune, with its turns and graces, presented no more difficulties than “Home, Sweet Home.” “Pat” Clancy is now on the eastern vaudeville circuit, and the nimble-fingered “Tom” Kiley is connected with The Knickerbocker Press of his native city.

A journey of twelve miles each way was made to Mr. Cronin’s house twice a week by the present writer, for two years, with unfailing regularity. Temperament and professional jealousy brought it all to an abrupt end without apparent cause. When in the humor, no man could he more obliging and liberal with his music. His muse needed no stimulation, and he would play on for hours at a time such tunes as memory presented, his features while so engaged remaining as set and impassive as the sphinx. An evening spent in the company of this most accommodating of musicians was an event to he remembered.

This genius, in whose expansive breast two conflicting elements struggled for the mastery was an adept in his peculiar style of free-hand bowing and slurring, but what seemed so easy and natural to him proved almost insuperably difficult to many whom he undertook to teach.