CHAPTER XXVIII

DANCING-A LEGITIMATE AMUSEMENT

IN every community there must be pleasures, relaxation, and means of agreeable excitement, according to Dr. Channing in his Address on Temperance, early in the nineteenth century; and if innocent ones are not furnished, resort will be had to those which are sinful. Man was made to enjoy as well as to labor, and the state of society should be adapted to this principle of human nature. A gloomy state of society is not well calculated to promote temperance, for the craving for excitement and entertainment - insistent as other human wants - will seek some channel for its gratification.

Public amusements bringing multitudes together to kindle with one emotion, to share the same innocent joy, have a humanizing influence, and among those bonds of society perhaps no one produces so much unmixed pleasure as music.

In another part of his Address the lecturer speaks of dancing as an amusement which has been discouraged by many of the best people, because it is associated in their minds with balls and their extravagances. On the contrary, dancing which involves a most healthy exercise should not be proscribed because the body as well as the mind feels its gladdening influence. No amusement seems more to have a foundation in our nature. The animation of youth naturally overflows in harmonious movements. It is an art almost as old as the rock-ribbed hills, and certainly antedates music, sculpture, and painting. Considered in the light of its best characteristics dancing is both ancient and honorable. It has ever been the refined expression of the poetry of the human body in motion. In ancient Greece dancing was an indispensible part of the education of youth. King James the First gave as a reason for permitting specific sports and pastimes, such as May Day games and Morris dances, and so forth, on special occasions, that “if these times be taken away from the meaner sort who labor hard all the week, they will have no recreation at all to refresh their spirits.” To many, dancing appears to be a frivolous waste of time and energy, while others regard it merely as an exhibition of tolerated childishness. To the strait- laced and puritanical, its practice is demoralizing, and it was this attitude which worked Such a radical change in the social customs of Ireland in the last half of the nineteenth century. Yet who can question the Wisdom of the clergyman who said that “people usually do more harm with their tongues than their toes.” “A Sunday with the peasantry in Ireland was not unlike the same day in France,)’ says john Carr, Esq., who toured Ireland in 1805. “Alter the hours of devotion a spirit of gaiety shines upon every hour, the bagpipe is heard, and every foot is in motion. The cabin on this day is deserted, and families in order to meet together and enjoy the luxury of a social chat, even in rain and snow, will walk three or four miles to a given spot.”

As every Irishman knows, the meeting place almost invariably was some cross-roads, where a piper or fiddler played enlivening music for the youthful dancers, while their elders gossiped in the old familiar way. Those more interested in athletics than in music and dancing, found no lack of that kind of entertainment also. Those national customs were observed until well beyond the middle of the nineteenth century, and no doubt it was the prevalent sentiment of the times that inspired the muse of F. Ambrose Butler in the following verses:

The Summer-sun is laughing down,

And o'er the heather glancing-

We’11 haste away ere close of day

To join the peasants dancing

Beneath the ivy-clothed trees

That guard the farmer’s dwelling,

And softly shake their leafy bells

While Music’s strains are swelling-

We’ll haste away, we’ll haste away,

Along the scented heather;

We’ll join the merry peasant band

And “trip the sod’, together.

From silent glen, from mossy moor,

From cabin lone and dreary,

They come-the friezed and hooded band

With spirits never weary,

With hearts so light that sorrows ne’er

Can break their sense of pleasure-

The Irish heart that laughs at care

Is blessed with brightest treasure.

We'll haste away, we’ll haste away, -

Along the scented heather;

We’ll join the merry peasant band

And “trip the sod,) together.

The stars will peep amidst the trees,

Their light with moonbeams blended,

Before the music dies away,

Before the dance is ended.

And joke and laughter, wild and tree,

Ring round the farmer’s dwelling,

And lithesome limbs keep measur’d time

Where Irish airs are swelling.

We’ll haste away, we’ll haste away,

Along the scented heather;

We’ll join the merry peasant band

And “trip the sod” together.

As long as happy Irish hearts

Are throbbing through the Nation,

As long as Irish exiled sons

Are found on God’s creation,

As long as music’s thrilling strains

Can wake a sweet emotion,

We’ll save the customs of our sires,

At home and o’er the ocean.

We’ll haste away, we,]] haste away,

Along the scented heather;

We’ll join the merry peasant band

And “trip the sod,’ together.

Such pastimes never interfered with religious devotions, for before the reformation only the hours for divine service were held sacred, and the rest of the day could be spent in sports if the people so chose, both in England and Scotland. Well, Dr. Joyce ruefully remarks: “The cross-roads are there still, but there is no longer any music or dancing or singing!” And by the way it reminds us of Goldsmiths lines in “The Deserted Village.”;

“These were thy charms, sweet village! Sports like these

With sweet procession taught e'en toil to please;

These round thy bowers their cheerful influence shed;

These were thy charms - but all these charms are fled.”

In those racy old times when the manners and usages of the Irish were more simple and pastoral than when Carleton penned his famous Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry, the author says dancing was cultivated as one of the chief amusements of life, and the dancing-master looked upon as a person essentially necessary to the proper enjoyment of our national recreation. Of all the amusements peculiar to our population, dancing was by far the most important., although it was admittedly declining in his day. In Ireland it may be considered as a very just indication of the spirit and character of the people; so much so that it would be extremely difficult to find any test so significant of the Irish heart and its varied impulses, as the dance when contemplated in its most comprehensive spirit. In those days no people danced so well as the Irish, according to Carleton. Music and dancing being in fact as dependent the one on the other as cause and effect, it requires little or no argument to prove that the Irish, who are so sensitively alive to the one, should excel in the other. Nobody, unless one who has seen and also felt it, can conceive the inexplicable exhilaration of the heart which a dance communicates to the peasantry of Ireland. Indeed, it may be considered inspiration rather than the enthusiasm which manifests itself in all their actions, for Irish movement is in striking contrast with English dancing, which Emil Reich describes as “the melancholy polishing of the ballroom door.”

The love of dancing appears to be inherent amongst the Irish, and constitutes a striking feature in the national character. Even poverty and its attendant evils, which might be supposed sufficient to depress the most elastic spirit, have not been able to extinguish the love of the peasantry for this amusement, that may be said to form an important part of their education in the first half of the nineteenth century. With them, observes Stirling Coyne, who wrote of the Scenery and Antiquities of Ireland in the late thirties, it is a natural expression of gaiety and exuberance of animal spirits - indicative of their ardent temperament; and it is doubtful if a more accurate test could he found to judge the character of a people than their national dances. By a people entertaining a passion for music the dance is never neglected. Dancing may be said to have formed a part of the education of even the poorest classes and the skill acquired from their humble teachers was regularly exhibited at weddings and other festivities.

A racial proclivity so conspicuous could not fail to attract the attention of travelers, who with scarcely an exception were favorably impressed. Take for instance Rev. Dr. Campbell, who made his observations in 1775: “The Irish girls are passionately fond of dancing, and they certainly dance well, for last night I was at a ball and I never enjoyed one more in my life. There is a sweet affability and sparkling vivacity in these girls which is very captivating. We frog-blooded English dance as if the practice were not congenial to us; but here (in Cashel) they moved as if dancing had been the business of their lives. `The Rock of Cashel’ was a tune which seemed to inspire particular animation.”

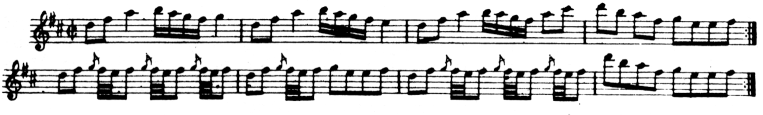

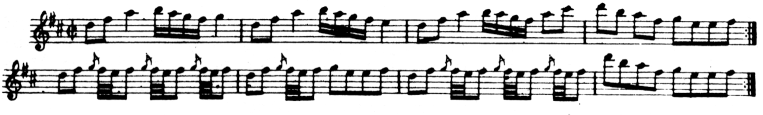

THE ROCKS OF CASHEL

from Aird's Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs Vol 4 circa 1793

|

|

Dr. John Forbes, F. R. S., in his Memorandums Made in Ireland in 1852 is no less appreciative of peasant dances and dancing. At Leenane, County Galway, he saw “at the inn door a blind old Irish piper, doing his best to amuse the company with some of the melodies of his country, of which he was certainly no mean exponent.

“After a time the piper began playing jigs, and a dance was immediately gotten up, first by a young woman and an old woman, and then by the young woman and our Galway driver. An active young fellow, he danced zealously and well; but the young woman acquitted herself incomparably. It is but speaking the simple truth in regard to the performance of this young woman to say, that it possessed every charm that an elegant and graceful carriage and the most thorough command over all the varied movements of the dance could give it. If she had not been long and strictly drilled in her vocation, she must have been born with all the aptitudes of original genius in this harmonious art. It was really wonderful to see how perfect her execution was on her rough platform, and with her naked feet; though I cannot but think that the nakedness of the feet added not a little to the charm of the whole.”

Testimony such as the above from the pen of a “Physician to Her Majesty’s Household” could not have been tinged with partiality, yet very different was the impression which piping and dancing made on the English novelist Thackeray while visiting Killarney in 1843. “Anything more lugubrious than the drone of the pipe,” he notes in the Irish Sketch Book, “or the jig danced to it, or the countenances of the dancers and musicians, I never saw. Round each set of dancers the people formed a ring; the toes went in, and the toes went out; then there came certain mystic figures of hands across and so forth. I never saw less grace or seemingly less enjoyment - no, not even in a quadrille.” None the less for his unappreciative comment, Thackeray’s sketch but proves the proneness of the Irish to indulge in the pleasures of the dance on all opportune occasions. Like his celebrated countrymen, Alexander Pope, Charles Lamb, Horace Walpole, and Dr. Johnson, the author of the Irish Sketch Book may have had no more ear for music than President Grant. So undiscriminating was the latter’s tympanum that when in the field during the Civil War he was always provided with a horse trained to distinguish and respond to bugle calls. The general is said to have acknowledged knowing but two tunes-one was “Yankee Doodle” and the other wasn’t.