CHAPTER XXX

ANCIENT IRISH DANCES

THE discussion of latter-day dances, such as the jig, reel, and hornpipe, or even the various forms of the Rinnce Fada or long-dance, already described at some length in Irish Folk Music, A Fascinating Hobby, was not contemplated in this work, yet it may be opportune to mention briefly other peculiar forms of the art which found favor in ancient times, and which are now obsolete, or for the most part forgotten.

The dance belongs to all countries and to all ages. As Mrs. Lilly Grove says, it has come to us through all myths, through all histories, through all religions, in spite of repressive edicts and anathemas, and, though modified by epoch and fashion, it adapts itself to the land of its birth, and has always and everywhere preserved much of its original character.

From the language of some ancient writers, the term dancing seems to imply little more than dancing in a circle with hands joined. As far back as the twelfth century there existed a dance in Ireland termed

FER-CENGAIL

It was of the class known in Germany and France as hopping dances. One person sang the melody, and all joined in the chorus, held each other’s hands as the name indicates, and moved in a circle.

CAKE DANCE

This dance is mentioned as a common and popular pastime at least as far back as the seventeenth century. It is not clear that it consisted of any peculiarity other than the object of its institution, which was seemingly to stimulate the dancers’ efforts-a toothsome cake being the prize for superior merit. The cake or prize was displayed on the top of a distaff or pole, in full view of all competitors. Not the least interested of those present was the piper, near whose seat was some receptacle - often nothing more than a hollow in the ground-into which contributions were thrown after each dance. The desire of the young swains to appear generous and offhanded in the eyes of the colleens added not a little to the piper’s prosperity.

In another form of this popular dance, the cake, decked out in held flowers or else encircled with apples, was awarded to the couple whose endurance outlasted their rivals in the dancing circle.

MAY-DAY DANCES

May-day festivals, as well as others of pagan origin, prevailed in the British Islands even in the late centuries. Maypole dances, common in England, were not unknown in Ireland. It was a favorite pastime on La Bealtinne or May Day, when the young men and maidens held hands, and danced in a circle round a tree hung with ribbons or garlands, or round a bonfire, moving in circles from right to left, to the accompaniment of their own voices singing in chorus.

Mrs. Anne Plumptre, in her Narrative of a Residence in Ireland (in 1815), remarked that dancing parties were “attended by a man and a woman, dressed in ridiculous figures, who are called the Pickled Herring arid his Wife, they make grimaces and play antics something in the style of a Merry Andrew.” Describing a dance she witnessed, Mrs. Plumptre continues: “The men were in number about forty, and, the tree being very tall, they all assisted in carrying it upon their shoulders. By the time they passed my friend’s house they were joined by a piper, who was seated across the tree, and thus borne in great state, he playing all the time, while the Pickled Herring danced along at the head of the procession.” The lady whom they intended to honor was “saluted with loud and repeated shouts.” Her permission being obtained for the Long-dance next day, “she was again cheered, and the people resuming their burthen, the piper struck up a merry tune, the Pickled Herring resumed his antics, and away they marched with great order and regularity.”

No music was found so suitable for Maypole dances among the English as the native bagpipe, as the tones of a fiddle would be almost inaudible in the midst of the general revelry.

RINNCE AN CIPIN, OR THE STICK DANCE

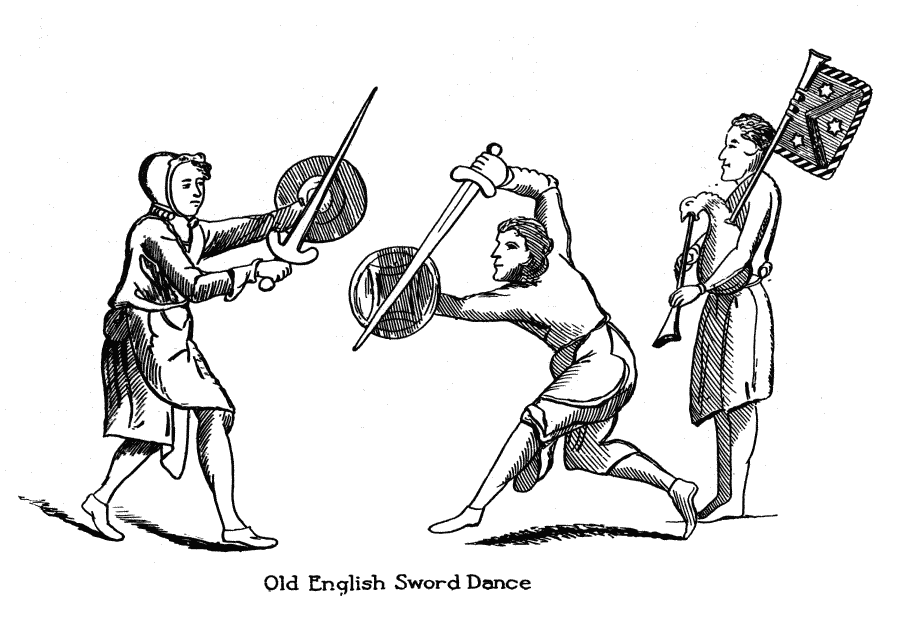

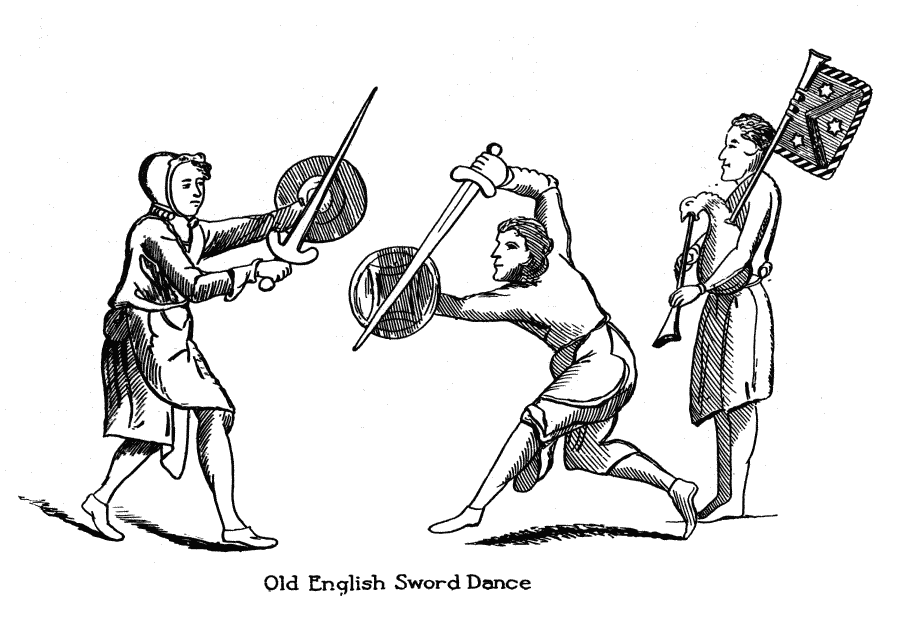

This was simply a degenerate form of the Sword Dance. Originally the latter was, both in Ireland and England, a duel with naked swords to the music of the bagpipe, as may be seen from the accompanying illustration taken from Knight’s Old England. In Scotland the “Gillie Callum” was danced over and around two crossed swords, great care being taken not to disturb their position in the exercise.

DROGHEDY MARCH on DANCING DROGHEDA

Now entirely obsolete, was described at much length by Patrick Kennedy in his Banks of the Boro. It was danced by six men or boys, each wielding a stout shillaleh. They kept time to the music with feet, arms, and weapons, and with their bodies swaying right and left. In the progress of the pantomime the movements became more complicated, and assumed the appearance of a rhythmic fencing or battle. This mimic war dance was performed to stately music, such as “Brian Boru’s March.,’

THE COBBLERS' DANCE

Then there was the Cobblers' Dance, in which the performers squatted on their haunches in a position even more cramped than when half-soling a shoe.

In this awkward attitude the dancer kicked out with each foot alternately in imitation of the rising step of the double jig. So ludicrous was the performance in its entirety that it never failed to arouse much merriment among the audience.

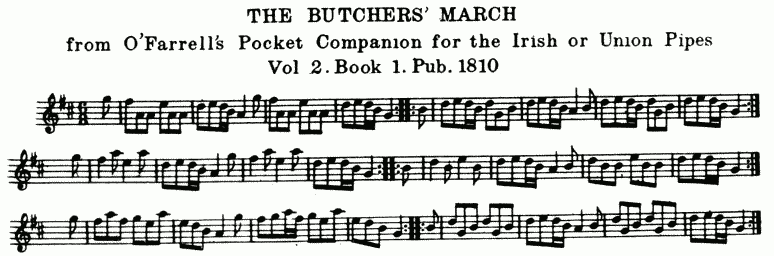

THE BUTCHERS’ MARCH

It requires no great stretch of the imagination to connect this ancient tune with the Rinnce Fada which Sylvester O’Halloran, the eminent historian, saw danced by the butchers on May Eve, in his native city of Limerick, away back in the eighteenth century.

In modern times the tune in two strains is danced as a double jig, yet the setting found in O'Farrell’s Pocket Companion for the Irish or Union Pipes, published in the first decade of the nineteenth century, consists of no less than six.

William Carleton, the novelist, born in 1798, mentions two ancient dances which few living in his time had witnessed. One called the

HORO LHIEG

was performed only at wakes, funerals, and other mournful occasions. It was only in remote parts of the country where the recollection of ancient usages still survived that any elucidation of such obsolete dances could be obtained.

There was another ancient dance executed by one man, not necessarily to the accompaniment of music. It could not, however, be performed without the emblematic aids of a stick and a handkerchief. This dance “was addressed to an individual passion, and was unquestionably one of those symbolic dances that were used in pagan rites.’,

CUL O GURRADH

An ancient pantomime dance so-called after the place where it was supposed to have originated, was peculiar to the County of Cork. It was performed in reel time by two persons who, in certain passages, simulated an attack and defense with closed fists in rhythmic movement to the music.

BATA NA BPLANDAIGHE or THE PLANTING STICK

In the planting of cabbages or potatoes, a pointed stick with suitable handle on the other end was used to facilitate the work. A pantomime of the process of planting with this instrument is said by Sir William Wilde to have been practiced in the Province of Connacht in olden times. A double jig named “Bryan O’Linn” in the O’Neill collections, is the tune to which it is said to have been performed.

COVER THE BUCKLE

Whether this well known name was originally applied to a tune or a special dance is not easily determined, so conflicting are the references to it by various Irish writers. In ,”Darby the Blast,” a song by Charles Lever, a couplet reads:

“As he plays `Will I Send for the Priest?’

Or a jig they call `Cover the Buckle.’ “

No room for doubt can be found in that reference. Yet in Hall’s Ireland, of about the same date, an infatuated swain tells of his charmer Kate Cleary “Covering the buckle, and heel on toe on the flure,” opposite his rival.

A respected County Leitrim piper born at the beginning of the last century, named James Quinn, and who had lived in Chicago for many years, played a double jig which he called “Cover the Buckle,” or “The Hag and Her Praskeen.” This tune is now generally known as “The Blooming Meadows,” a simple version of which by that name is to be found printed without comment in Dr. Joyee’s Ancient Irish Music.

In a work of such detail as A Handbook of Irish Dance, by O’Keeffe and O’Brien, one naturally expects to have the question settled definitely. Not so, however. “Cover the Buckle” is merely included in a list of “Figure” or “Set” dances “usually associated with tunes which are irregular in structure.”

We find some solid ground at last in the writings of Shelton Maekenzie, who was horn at Mallow. County of Cork, in 1809. In an article on “Irish Dancing Masters” the author describes “that wonderful display of agility known in my time as `Cover the Buckle’ - a name probably derived from the circumstance that the dancing-master, while teaching, always wore large buckles in his shoes, and by the rapidity of motion with which he would make his `many twinkling feet’ perpetually cross; would seem to `cover’ the appendages in question.” While thus exhibiting his skill and agility, the dancing-master was encouraged with such exclamations as “That's the way,” “Now for a double cut,” “Cover the buckle, ye divel,” “Oh, then, 'tis he that handles his feet nately,” and so on, until he had literally danced himself off his legs.

VARIOUS SPECIAL TUNES

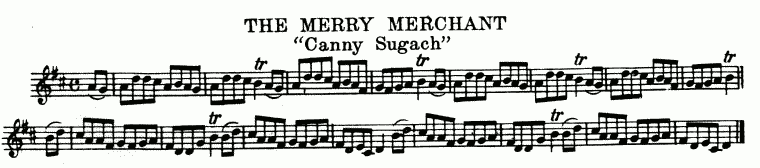

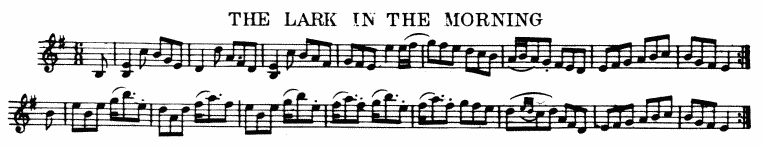

Besides the tunes previously named in this chapter, many others have been mentioned in connection with “special” dances, now for the most part if not entirely forgotten. Principal among them are: “The Carpenters’ March,” two tunes of that name entirely dissimilar in metre and composition being in the Petrie collections; “The Priest in His Boots,” “The Lark in the Morning,” “The Drogheda Weavers,” “The Humors of Limerick,” “The Rocky Road to Dublin,” “Drops of Brandy,” “The Fairy Dance,” “The High Caul Cap,” “Shuffle and Cut,” and “The Canny Sugaeh” - also known as “The Merry Merchant,” and “The Merchant’s Daughter.”

A rollicking Irish song was sung to this air at least as late as the middle of the nineteenth century, and the agility required to dance it properly was proverbial, for nothing more complimentary could be said of a young man’s activity than to remark that “he could dance the `Canny Sugach.’”

And, while we are discussing the subject of “special,’ tunes of ancient lineage, the occasion seems opportune to present to our readers “The Lark in the Morning,” the rarest and certainly not the least interesting of its class, for it possesses marked individuality all its own.

This tune was first published in O'Neill’s Music of Ireland, and the story of its recovery and preservation needs no apology for its presentation here.

James Carbray, a native of Quebec, but now a resident of Chicago, when studying music in his young days picked up some fine tunes from an old Kerry fiddler named Courtney, long settled in Canada. Many years later Mr. Carbray, amiable and accommodating gentleman that he is, recorded them on an Edison phonograph and forwarded the rolls to Sergt. James Early of the Chicago police force. It didn’t take John McFadden long to memorize “The Lark in the Morning,” and we may be sure it lost nothing of the blas or graces at his hands in transmission to Sergt. James O’Neill’s notebook, and subsequently in its final setting herewith submitted.

While the display of any form of levity at a wake subjected the Irish to obloquy and ridicule, the Cushion Dance often concluded a country wake in “Merrie” England.

Kissing appeared to have been an essential part of most English dances, a circumstance which probably contributed not a little to their popularity. This custom, according to Mrs. Lilly Grove, author of Dancing - a renowned work - still survives in some parts of England, and when the fiddler thinks the young people have had music enough he makes his instrument squeak out two notes which all understand to say “Kiss her.” At the end of each strathspey or jig a particular note from the fiddle used to summon the rustic to the agreeable duty of saluting his partner with a kiss, that being his fee or privilege according to established usage.